Ideas into movement

Boost TNI's work

50 years. Hundreds of social struggles. Countless ideas turned into movement.

Support us as we celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2024.

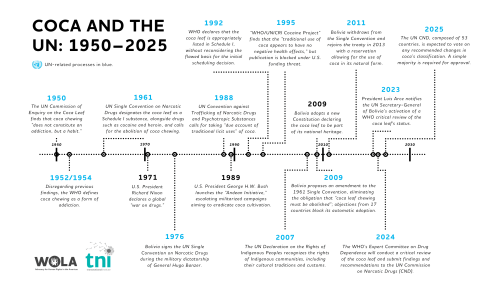

Nearly 75 years after the United Nations called for the abolition of traditional uses of the coca leaf, the world will have a new opportunity to correct this grave historic error. The World Health Organization (WHO), at Bolivia’s initiative, will conduct a ‘critical review’ of the coca leaf over the next year. Based on its findings, the WHO may recommend changes in coca’s classification under the UN drug control treaties. The WHO recommendations would be submitted for approval by the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), with voting likely in 2025.

Changing coca’s status in the drug treaties can vindicate the rights of Indigenous peoples and open legal international markets for natural coca products, fortifying Andean economies while bringing coca’s benefits to increasing numbers of people around the world. The coca review process can also help modernize a drug treaty system still mired in the colonialist biases and racial prejudices from which it arose in the mid-twentieth century. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and the Transnational Institute (TNI) will be monitoring the coca review process closely and examining key aspects of the debate. In this first issue of the Coca Chronicles, we discuss four basic questions. You can read the second issue 'Coca Leaf Progress at the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs' here.

Illustration by Anđela Janković

The first step in the process that Bolivia has initiated will be a study undertaken by the WHO Expert Committee, based on the available scientific literature, inputs from treaty Parties (including the dossier that Bolivia already submitted) and contributions from civil society organizations. Depending on the findings of its study, the Expert Committee will then submit any recommended changes in coca’s classification to the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), the Vienna-based UN drug policy body. The 53 countries that comprise the CND would then vote on the recommendations, with a simple majority required for approval.

To ensure that the WHO conducts its scientific review in as comprehensive, inclusive and multi-disciplinary manner as possible, Bolivia’s ‘Supporting Dossier’ highlights numerous dimensions that the review process must be sure to address. Given the centrality of coca in the cultural, ceremonial and traditional medicinal practices of many Indigenous peoples in the Andean-Amazonian region—and given the grotesquely prejudiced accounts of Indigenous peoples that drove the initial decision to classify coca as a narcotic drug—the dossier underscores the imperative of ensuring ample inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the review process, as well as experts on ‘traditional medicine.’

The WHO’s critical review is expected to be completed by the end of 2024, setting the stage for voting as early as the March 2025 session of the CND. The ideal outcome, in the Bolivian government’s view, would be for the WHO to recommend removing coca entirely from the schedules of the Single Convention. The WHO could in principle recommend moving coca to the less restrictive Schedule II, alongside codeine and other milder opioids. But a Schedule II designation would mean that coca leaf would still be limited to medical and scientific purposes, albeit subject to lower levels of administrative control. Any recommendation for changing coca’s current Schedule I status is likely to face stiff headwinds in the CND, where assembling the necessary votes to enact a change in coca’s status would likely encounter significant obstacles.

For enlargement of the timeline click here.

A decade ago, when Bolivia exited from and then succeeded in rejoining the Single Convention with a reservation defending the traditional use of the coca leaf within Bolivia, the United States was staunchly opposed. President Barack Obama’s government spearheaded a campaign to block Bolivia’s reservation. In lodging its formal objection, the Obama Administration highlighted U.S. concerns that “Bolivia’s reservation is likely to lead to a greater supply of available coca, and as a result, more cocaine will be available for the global cocaine market, further fueling narcotics trafficking and related criminal activities in Bolivia and the countries along the cocaine trafficking route.” All G8 countries and several other European countries joined the U.S. government in its objection. Ultimately, the U.S.-assembled coalition fell far short of preventing Bolivia from re-acceding to the treaty, and since then both Mexico and the Netherlands have formally withdrawn their original objections. But the U.S. rationale for opposing Bolivia’s reservation back in 2012 will almost certainly re-emerge as debates ignite around the WHO’s critical review of coca. Especially in Europe, new concerns have emerged about rising cocaine consumption and increasing levels of violence associated with the illicit cocaine trade.

As President Arce emphasized in his June letter to UN Secretary-General Guterres, Bolivia’s “intention is not to diminish in any way the international control of coca cultivation and of the use of coca leaves for the illicit production of cocaine.” Even if the coca leaf were to be deleted entirely from the schedules of the Single Convention, the treaty contains specific articles that would still require Parties to take measures to prevent coca leaf from being used as a raw material in the illicit production of cocaine. Moreover, as the accompanying dossier argues, the “fear that a legal international retail market in coca tea, coca flour, ypadú/mambe, and other coca-based products could become a source of clandestine cocaine production, is completely misplaced.” The process of extraction is too complicated to even consider using a kilo of tea bags or mambe to extract a gram of cocaine, and as a matter of economics, such effort simply wouldn’t pay.

Thus far two countries—Colombia and Mexico, both of which are CND members—have publicly expressed support for the review process initiated by Bolivia. Any eventual recommendation by the WHO to reschedule the coca leaf, or to remove it entirely from the Single Convention, will need backing from a much larger group of countries in order to be approved by the CND. The CND itself has become an increasingly polarized space in recent years, and the coca review can be expected to trigger highly contentious debates.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights recently warned that the current drug control model “perpetuates existing patterns of discrimination, including against people of African descent, women and indigenous peoples,” calling to end the ‘war on drugs’ and to “focus on transformative change, crafting drug policies which are based on evidence [and] which put human rights at their centre.” An evidence-based review of the classification of the coca leaf is an important step toward transforming a treaty system that appears frozen in time. The review now getting underway provides an extraordinary opportunity to undo a grave historical injustice, resolve the undeniable conflict between the Single Convention and Indigenous rights, generate licit livelihood opportunities for coca growers, contribute to peacebuilding in the Andean region, and allow the rest of the world to partake in the coca leaf’s beneficial properties.