‘Authoritarian corpopulism’ supports the rise of sugarcane and oil palm agribusinesses in Guatemala

Temas

Regiones

‘Authoritarian corpopulism’ relies on persuasion and selective violence, cloaked in the rule of law and backed by the state, to advance big business agriculture and resource extraction.

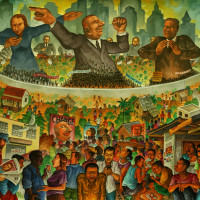

Photo by the author.

The current debate on populist political regimes has rightly focused on the ultra-conservative authoritarian wave sweeping the world. Does this mean authoritarian forms of government are only reserved for those living in countries under charismatic right-wing populist leaders? And is it only through such iron-fist rulers that authoritarian populism unfolds?

In short, no; there’s more to authoritarian populism today, and the role of large agribusiness corporations intimately linked to the state and elites is an important part of the story.

In Guatemala, a long history of despotic and violent populist rulers embarked in a transition to liberal democracy 30 years ago. Amid the agro-environmental and capitalist transformations that have occurred since, a new politics of class domination has emerged.

These politics are shaped by the rise of what I call ‘authoritarian corpopulism’, whereby corporates are deeply implicated alongside the state. Specifically, ‘authoritarian corpopulism’ in Guatemala stands for the political agenda of the white oligarchic-bourgeois owners of sugarcane and oil palm agribusinesses ruling over the countryside.

Multiple and convergent global crises in Guatemala

Since 2005, sugarcane and oil palm plantations and processing plants have spread like wildfire, and the small Central American country has been thrust into the position of a leading world producer and exporter of multiple cane and palm commodities.

At the same time, agro-ecological, social and policy structures were reconfigured to meet the particular challenges of an “agro-extractive capitalist project” led by a local oligarchic bourgeoisie with dense ties to foreign capital.

Supporters of this agribusiness expansion use an ‘authoritarian corpopulist’ agenda to recast cane and palm commodity production. Instead of just another accumulation project, this is carefully moulded into one that claims to be able to feed the world, generating green energy and cooling down the planet, while at the same time sponsoring employment and stimulating economic growth. To make sure everyone gets that message – but especially customers – cane and palm companies have embarked on a campaign to promote themselves as responsible.

With this purpose, the authoritarian corpopulist agenda involves two interlinked steps. The first is the “multi-stakeholderization” of sugarcane and oil palm commodity chains, creating networks beyond shareholders committed to such corporations.

A second step is swapping the “bullets and beans” agenda of earlier authoritarian-paternalistic military regimes in Guatemala, used to counter the “communist threat” during the 1962-1996 internal armed conflict, in favour of populist persuasion and selective violence, now cloaked in the rule of law, and aimed at countering “anti-developmentalism” and “eco-hysteria.

Resource plunder and labour hyper-exploitation

Authoritarian corpopulism hinges on a pro-social branding of the sugarcane and oil palm complexes, with the strategic support of the state.

The result is the reproduction of the racialized class hegemony of the white creole oligarchic-bourgeoisie. In addition to the policy concessions that are part of populist political regimes elsewhere (e.g. public grants and multi-stakeholder governance), authoritarian corpopulism in Guatemala involves a series of fixes that companies implement, affecting labour, land, finance, knowledge and technology, and ecological relations.

These act to soften the blow of flex cane and palm commodity production on people and the environment, while simultaneously increasing labour and land productivity, expanding plantations, accessing new funding sources, reducing production costs, and expanding cane and palm commodity production.

Authoritarian corpopulism in action

The authoritarian corpopulist agenda relies on a number of strategies.

The “trojan horse” strategy has a two-sided aim: building sugarcane and oil palm companies’ legitimacy at the grassroots, and co-opting the initiatives of challengers.

A new consensus must be mobilized and to this end, corporations deploy "discursive flexibility", entailing strategically switching between plausible narratives justifying the value of sugarcane and oil palm production for different audiences.

This is complemented by a “staying alive” contention strategy that reinforces accumulation and seeks to reproduce the hegemony of the oligarchic bourgeoisie through fixes to productive relations that ameliorate the adverse socio-ecological impacts of sugarcane and oil palm commodity production.

And for dissenters, the “pocketed claw” strategy is employed to deter and punish, especially those threatening assumed rights to property and freedom of enterprise. This authoritarian and violent strategy relies on a combination of tactics. Recourse to the “rule of law” entails the mobilization of the ideological and repressive apparatuses of the state. And a “jungle law” tactic, that involves illegal violence in organized but covert forms, is used to eliminate selected challengers, hiring “barefoot thugs” from the rural population surplus to the agro-extractive capitalist project.

Responses and future trajectories

Corporate-led and state-backed palm and cane commodity production represents a prime example of the agro-extractive capitalist project seen in many rural spaces across Central America. Given a populist gloss, but implemented with force and violence, it also generates reactions. Dissent, unrest and contestation is common.

In Guatemala struggles against land dispossession by sugarcane and oil palm companies include environmental, health and labour grievances, alongside demands for strengthening livelihoods, especially through the intensification of swidden farming systems.

Many are calling for the reaffirmation of local sovereignties, articulated in terms of a “defense of territory”. Others find accommodations with the dominant, powerful force of authoritarian corpulism. This can happen in two ways. Some argue for “inclusive, ethical and sustainable development”, ameliorating the worst of cane and palm commodity production. This is advanced by state actors and big transnational conservation and development NGOs, acting as gatekeepers in multi-stakeholder platforms of corporate performance certification, like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

Others accommodate through criminal incorporation into the agribusiness labour regime, either as narco-outgrowers or as corporate thugs, as well as through criminal entrepreneurship elsewhere, usually as hitmen in narco-trafficking cartels or in criminal “mara” gangs in Guatemala City.

Authoritarian corpopulism reshapes the political terrain of agro-environmental and capitalist transformations through alliances between corporates, the state and a Guatemalan white, oligarchic bourgeoisie permeating both of the foregoing.

By legitimizing cane and palm commodity production through populist moves, and recurring to force when needed, dissent is suppressed and accommodations forged. The result is a new politics of class domination in rural areas which trajectory is still to be seen.