Countering gender panic How Guatemalans challenged the erosion of democracy

Temas

Regiones

In 2023, far-right politicians tried to use tried and tested anti-gender narratives to win and consolidate power, but this time they failed and a center-left party came to power. What happened and what are the lessons for activists worldwide challenging anti-gender narratives?

Photo by Shalom de León on Unsplash

‘Life and Family’ a right-wing rallying cry in Latin America

The far-right depends on fabricating an ‘enemy’ to gain and sustain power. Instilling fear is the key component. These political views need their supporters to believe that the ‘enemy’ poses such a threat that it must be stopped by any means necessary: often, in Guatemala, this has included sacrificing democratic institutions in the process. After instilling fear of this supposed enemy, the far-right presents itself as the solution to destroy it. This redirects scrutiny towards the fabricated enemy and away from the far-right, and positions itself as the saviour from this ‘enemy’. The same strategy has been used to develop common enemies of immigrants and minorities, both religious and sexual.

This strategy is widespread. According to a recent Outright International report, during the 2024 electoral cycle, political parties in at least 27 countries used anti-gender narratives as part of their campaigns – including Brazil, Chile and Uruguay.

Over the last decade, local and international political and religious leaders have constructed ‘gender ideology’ as one of the most prominent ‘enemies’ in Latin America. ‘Gender ideology’ is a catch-all concept that loosely refers to and stigmatises feminism, sex education, sexual and reproductive rights, and the rights of women and sexual and other minorities. This term was popularised in the 1990s by Catholics opposed to the use of the word gender in the Declaration following the 1995 United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, particularly through the publication of ‘The Gender Agenda’ by the conservative Catholic journalist Dale O’Leary and later ‘The Salt of the Earth’, an interview with Cardinal Ratzinger (subsequently Pope Benedict XVI). It was then spread by the Vatican in the 2000s and popularised by right-wing politicians in Latin America in the 2010s.

That the concept of gender as such a contentious issue is rooted in its centrality to political, social and personal identities and, thus, its relationship to religious and spiritual beliefs. This makes it an easy target for fearmongering. As a 2025 research report by the Othering and Belonging Institute at Berkeley argued:

‘[gender and sexuality] are deeply rooted aspects of identity, shaping how individuals understand themselves and relate to others. If authoritarians are able to regulate these most intimate aspects of ourselves, they have a starting point for control at a very personal level. Gender and sexuality are also tied to longstanding social norms and expectations, and thus hold significant cultural and emotional weight – making them especially vulnerable to manipulation by authoritarian actors.’

This manipulation is evident in the spread of fear of ‘gender ideology’ as a threat to religious beliefs about ‘life from conception’ and ‘traditional families’. ‘Gender ideology’ is usually understood as a euphemism for banning abortion, sex education, same-sex unions and trans rights, but its vagueness allows for malleability in its meaning. In the Americas, far-right actors present themselves as the ‘protectors of life and family’, offering a solution to the ‘gender ideology problem’. The ‘defence of life and family’ can include ‘traditional ways of living’, ‘traditional values’ and is sometimes even distorted to refer to the protection of children’s rights – in opposition to the ‘threat of gender ideology’. The Latin American far-right often further extends the ‘protection of life and family’ in opposition to what they understand as ‘populism’ and ‘Marxism’, in a vague reference to social justice movements and, particularly, feminist movements – local and international.

Both ‘gender ideology’ and ‘life and family have become empty signifiers across the region. In Guatemala, they can be traced back to 2013, when the Organization for American States (OAS) conference was held in Antigua Guatemala. It brought together conservative local and international groups – including the Asociación Familia Importa, Human Life International, and the Latin America and Caribbean Episcopal Council – to protest against the adoption of the Inter-American Convention Against All Forms of Discrimination and Intolerance. These groups accused the Convention of ‘promoting homosexuality’ and ‘fostering religious persecution’ and planted the seed of what would become a wave of anti-gender movements, narratives and policies over the next decade.

In 2016, a group of Catholic leaders from across Latin America convened in Mexico and formed El Frente Latinoamericano por la Vida y la Familia. The following year, politicians and Evangelical Christian leaders from Mexico, Central America and the US convened in El Salvador in a roundtable on ‘religious freedom’ – with the guest presence of then mayor Nayib Bukele, now the country’s authoritarian president – in which ‘protection of Life and Family’ was one of the main issues discussed.

Since then, these narratives on the ‘protection of life and family’ have become crucial in the far-right authoritarian toolbox. These narratives have been able to tap into the conservative Christian cultural majority and manipulate them to resonate with people’s deepest social and political concerns by pinning them on ‘gender ideology’. They have been able to secure power by presenting themselves as allies with the population’s common interests – the so-called protection of what they value most – their families, their lives, and their own traditions.

As the renowned philosopher Judith Butler stated: ‘The result is that gender, now firmly established as an existential threat, becomes the target of destruction’.

Gender Ideology and the Rise and Fall of the Anti-Corruption Movement in Guatemala

2015 marked a revolutionary year in Guatemala. Between April and September, citizens took to the streets across the country in increasingly massive demonstrations against government corruption. That April, the Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG) (the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala) announced that it had uncovered a scheme of customs fraud that involved then President Otto Pérez Molina, Vice President Roxana Baldetti, and their right-wing political party Partido Patriota. Both resigned in response to the protests, and were later prosecuted for their role in the customs fraud scheme.

In the following years, the movement gained traction as the CICIG revealed further corruption cases. However, the fight against corruption soon came to a halt during the government of Jimmy Morales (2016–2020). In 2017, the CICIG revealed a scheme of illegal electoral financing of his 2015 presidential campaign. The criminal prosecution of the heads of major companies associated with the scheme terrified and angered the economic elites. Previously, they had been crucial allies of the CICIG and the anti-corruption movement. But when their economic interests were threatened, they did everything they could to stop the CICIG.

How could a group of economic elites, in coalition with a corrupt government, convince the general population to protect their interests in such a context? They had to act fast, and they had to be convincing.

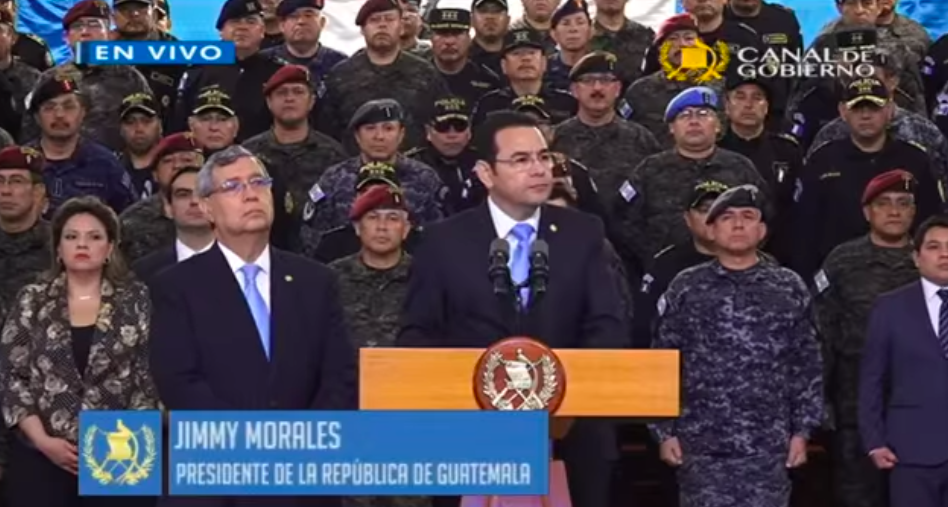

This is where the anti-gender movement – particularly the discourse of ‘protection of life and family’ – played a crucial role in the dismantling of the CICIG and, as a result, in the further erosion of democratic institutions. While Jimmy Morales and his allies were still being investigated for corruption, his party in Congress introduced Initiative 5272: Protection of Life and Family, a timely policy distraction. They also accused the CICIG of having a ‘globalist agenda’ that sought to impose ‘gender ideology’ in Guatemala, creating a new common enemy for the country. This polarised society and weakened the momentum of the anti-corruption movement. In September 2018, Morales announced he would not renew the CICIG’s mandate. He was surrounded by military officers in a press conference where he stated:

‘Guatemala and our government believe in life and family based on marriage between man and woman. Our government and Guatemala believe and want elections free from intervention. Guatemala is a friend and ally of our friends. God bless us’.

|

| 2 September 2018. In a press conference, President Jimmy Morales expresses his decision not to renew the CICIG mandate. |

This new political climate, without the CICIG and a weakened anti-corruption movement, plus anti-gender tactics at centre-stage, favoured the far-right party Vamos and the return of Alejandro Giammattei in the 2019 elections. His political campaign also relied heavily on an anti-gender discourse. During his government (2020–2024), Congress approved Initiative 5272 –but shelved it after international outrage – and he set up the Public Policy for Life and Family 2021-2032, a policy that allegedly planned unspecified programmes to ‘protect life from conception until natural death’ and ‘strengthen families’. His administration also signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Valerie Huber’s US anti-gender organisation, the Institute of Women’s Health. While these tactics positioned him as a ‘protector of life and family’ at the same time he continued to participate in corruption and anti-democratic schemes, including bribery and attempting to interfere with the 2023 election results.

Although significantly smaller than in 2015, in 2021 there were protests against corruption in the administration. Giammattei retaliated with authoritarian tactics. Police brutalised protesters. The Public Ministry weaponised criminal investigations against activists, journalists and former public officials – many still ongoing. In this context, the 2023 elections looked grim. Among the 30 political parties registered, numerous were linked to corruption schemes, military elites, and drug barons. It was feared that having another far-right party in power would be able to install complete fascist rule.

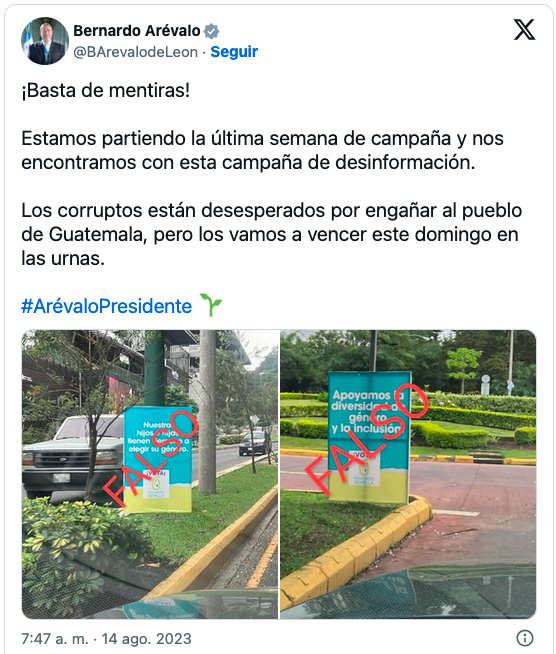

One small, grassroots party was the exception. The centre-left party, Semilla, was formed by anti-corruption activists and academics led by Bernardo Arévalo, a son of the former president Juan José Arévalo (1945–1951). Semilla, with a modest, crowdfunded budget, was completely overlooked as a real contender in the elections. The party polled at less than 3%. It was, then, quite a surprise when Arévalo came second in the first round of elections in June 2023. The party represented something the country had been yearning for since 2015: the end of state corruption. Rapidly, the opposition deployed one of its tried-and-tested tactics to demobilise democratic movements: anti-gender narratives. There were smear campaigns and Arévalo was accused by other political parties of favouring ‘gender ideology’, including by the runner-up Unión Nacional de Esperanza (UNE), conservative influencers and media, right-wing business leaders, and even an army of fake social media accounts. Anonymous pamphlets were distributed in the streets of Guatemala City listing the supposed ‘gender ideology’ reforms – vaguely referring to same-sex marriage and legal gender identity recognition – that Semilla would introduce if elected. Fake billboards went up with Semilla’s party logo stating they ‘support diversity and inclusion’ and ‘our sons and daughters have the right to choose their gender’.

In an interview, a radio host questioned Arévalo about his participation in his daughter’s lesbian wedding in Mexico earlier that year. Economic elites also accused Semilla of having ties with communist/socialist/populist groups. In an electoral debate with the runner-up presidential candidate Sandra Torres, she accused him of being ‘against family, life and religious freedom’ and warned that ‘he would destroy private property and install gender ideology in classrooms’.

This peculiar mixture of anti-communist sentiment with fearmongering about ‘gender ideology’ demonstrates the close relationship between anti-gender narratives and the neoliberal interests of economic and political elites. It connected with how these were deployed when the anticorruption movement threatened the status quo in around 2017. It also sheds light on the cracks in the anti-gender tactic in Guatemala.

|

| 24 August 2023. Bernardo Arévalo’s social media post addressing the disinformation campaign against the political party Semilla during the electoral cycle. |

In response to the constant claims of ‘promoting gender ideology’, the Semilla party strongly denied holding these beliefs. They attributed the smear campaign to ‘corrupt politicians seeking to trick the people’. This move was strongly criticised by Semilla’s progressive voter base, as the party did not directly challenge the weaponisation of ‘gender ideology’ narratives and ‘played it safe’. Semilla and its allies focused instead on creating counter-narratives that showcased the party’s commitment to the fight against corruption in all public institutions.

The Semilla campaign was characterised by grassroots organising, a small budget and the support of many volunteers. Ordinary citizens organised rallies, made and distributed posters and home-made merchandise, and posted videos in social media replicating the ‘fight against corruption’ message. The campaign explained concrete strategies the party planned to implement, including: reducing the salaries of members of congress (commonly perceived as the source of corruption), reducing living costs by regulating the price of electricity, and forming an anticorruption commission, among others.

Despite Semilla’s efforts to separate itself from the smear of ‘gender ideology’ campaigns and promote its progressive government plan, it still seemed unlikely that Arévalo would win. To many civil society organisations (CSOs), activists and the general population it still seemed hopeless. A small, grassroots party had never won the elections before. Furthermore, the use of anti-gender narratives had previously succeeded in protecting the interests of military, economic, and political elites for almost a decade.

Except, on 20 August 2023, it finally failed.

To everyone’s disbelief, Arévalo was elected president with 58.01% of votes cast in the second-round run-off. Semilla became the third party with the highest number of seats in Congress. The gender panic planted by ‘gender ideology’ narratives was not able to override the anti-corruption sentiment.

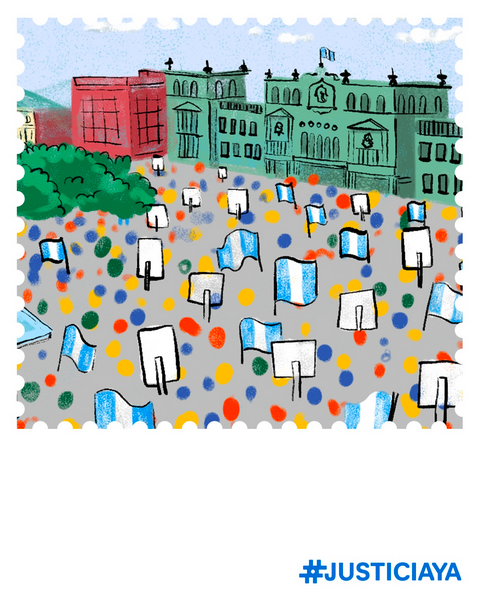

Almost immediately, on 12 September, the Public Ministry seized the electoral ballots, accusing Semilla of electoral fraud. However, the public fiercely defended the democratic vote, united by this anti-corruption sentiment and led by Indigenous movements. Activists called for a peaceful strike and for 21 days there were demonstrations, road blockades and border closures all over the country. Despite ongoing attempts to interfere with electoral results in the following months, Arévalo finally took office on 15 January 2024.

Defending Democracy: Lessons from Guatemala’s 2023 general elections

Regardless of the current challenges and future of the Arévalo administration, the 2023 Guatemala elections offer a valuable lesson in how democratic movements can successfully counter authoritarian narratives – a lesson that can be applied worldwide.

The Guatemalan case confirms a key far-right tactic: the fabrication of an enemy in an effort to install fear, polarise society, divide social movements, and to create a distraction from their authoritarian actions. When the anti-corruption movement became a threat to the elites’ economic interests associated with the far-right in 2017, they invented and implemented the enemy of ‘gender ideology’ – which was already a far-right device spreading rapidly in the region – to weaken the anti-corruption movement.

Alejandro Giammattei was also able to advance the anti-democratic and authoritarian project by creating distraction and social polarisation on the issue of ‘protection of life and family’. This included the persecution of journalists, activists and former public officials, who were also presented as enemies of the nation.

However, the 2023 elections demonstrate that the manipulation of a fabricated enemy like ‘gender ideology’ can fail when countered by a more powerful narrative rooted in people’s needs, experiences and history. Although the anticorruption movement had been significantly weakened, the belief that corruption was the true enemy had deeply permeated throughout Guatemala’s population. Corruption caused universal indignation across diverse political, ethnic, and socioeconomic contexts. Indignation was a unifying emotion more potent than the manipulated fear of a ‘distant and inconsequential’ issue like gender ideology. Particularly so when corruption is perceived as a key driver of urgent issues that Guatemalans are deeply concerned about, such as poverty and economic inequality.

When Arévalo was perceived as a candidate who could legitimately address these urgent issues, the whipped-up fear of ‘gender ideology’ subsided. In its place, an organic feeling of indignation towards injustice fuelled citizens’ election of a democratic leader and to defend their democratic vote. This organic indignation, as the scholar and activist Diana Roca argues, is the kind of force that can shape democratic futures:

‘Emotions are not merely reactions to external events; they are powerful forces shaping collective futures. Embracing this understanding can lead to more effective strategies for organizing, mobilizing, sustaining, and imagining alternative futures.'

Although gender is an incendiary issue because of its personal, religious, political, and cultural significance, material concerns are far more engaging. In particular, as anti-gender tactics are usually employed to achieve neoliberal means, focusing on people’s material needs can overcome such manipulative tactics. Countering the far-right depends on finding unifying forces and redirecting them towards addressing the real causes of social problems. As the Narrative Initiative explains:

‘[...] We need narratives that align with our long-term goals and put us on the path to reach them. We know from research that many audiences are hungry for any alternative, for another way forward that moves beyond fear and hate and reaches toward belonging and possibility’.

In the case of Guatemala, focusing on anti-democratic actors as the drivers of corruption led to defending democratic elections, and the election of a democratic leader, largely through a grassroots, popular campaign. This is an important lesson on how counternarratives against far-right tactics need to place the population’s true needs centre stage and address the root causes of their concerns.

This case also resonates with similar successful counternarratives against far-right rhetoric, such as the recent win of New York City mayoral elections by Zohran Madmani. Despite the anti-gender, anti-immigrant and nationalist rhetoric used against him, his closeness to ordinary people, a grassroots campaign, and addressing basic concerns like the cost of living proved to be more effective than his opponents’ fearmongering. Outside the electoral sphere, such counternarratives are also crucial in protecting democratic processes. During his recent trials in Brazil for an attempted coup, the former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro lost some support when his ally Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs on the country if he was not released. Citizens perceived Bolsonaro as willing to betray the population’s economic needs to save himself and his family.

In a global context where anti-gender narratives are continually being weaponised to erode democratic institutions, this is an urgent issue. It is imperative to understand the common sentiments that people share across sectors, identities, geographies, and political persuasions. Narratives that bring people together – rather than dividing them – can be harnessed to build more resilient communities, social movements and institutions. Through collective power there is hope for more democratic futures.

|

| 10-year anniversary poster of the 2015 anti-corruption protests in Plaza de la Constitución in Guatemala City (2025) by the CSO Justicia Ya (Justice Now). |