Combatting Energy Poverty in El Cua, Nicaragua

Topics

Regions

Community members banded together in a show of solidarity, committing to collective ownership and equity, transparency, and direct participation in the development and management of their energy infrastructure. This impressive collective commitment has transformed a once-rural village of just over 3,000 residents in the 1980s into a thriving urban metropolis of more than 40,000 residents today.

Thirty years ago, an energy revolution quietly got underway in the northern highlands of Nicaragua. In the 1980s, the international community was focused on the fight between the US-backed Contra rebels and the democratic socialist Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) for control over the country. At the same time, communities that had repeatedly been bypassed for modern infrastructure development organised to form the Association for Rural Development Workers (ATDER-BL), with the goal of providing their own electricity.

Energy dreams

The creation of ATDER-BL began with the dream of an American engineer named Benjamin Linder, who moved to the northern town of El Cua in 1985. Lamenting the lack of electricity in the region, Linder helped to bring together a team of volunteers from the community to build a hydroelectric plant in San Jose de Bocay.[1] At that time, this 235 kW plant was the biggest hydropower project in the country, and it provided electricity to families who had lived without power for generations. [2] Furthermore, the region suffered from a lack of infrastructure such as roads and municipal services, as well as access to capacity building, tools and training for residents. Together, this contributed to high rates of poverty and unemployment among community members. These local conditions, and the growing frustration about the civil war, stimulated people to become involved in building the community energy facilities. With no recourse to national support, community members became their own best resource, and felt a sense of control and pride in tackling these immense challenges.

Today, this same commitment to democratic values – including solidarity, participation, equity and transparency – is still integral to the design and sustainability of every project that ATDER-BL undertakes.[3] The association aims to build small economies and to strengthen community ties through each of its participatory projects. It is mainly comprised of local engineers, designers, machinists, lineworkers, administrators, builders and community members. They are mainly involved in the construction of small-scale hydroelectric plants and micro-turbine hydraulics, but also work on larger-scale hydroelectric plants, drinking water systems, mechanisation, technical training for community capacity building, engineering land surveys and watershed conservation. The association operates principally within the departments of Jinotega and Matagalpa, where some of Nicaragua’s densest populations of families lacking access to electricity are located.

A model based on solidarity and community

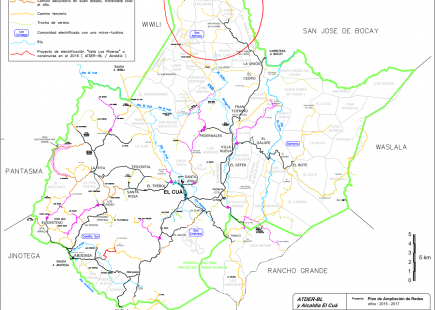

ATDER-BL has a solidarity-driven, community-focused development model that was designed collectively – through trial and error and numerous rounds of consultation – by local engineers, builders and community members. All of the association’s projects prioritise local leadership, collective ownership and capacity building. ATDER-BL designs and installs small-scale hydroelectric generation plants, which are in turn managed, operated, partially financed and maintained by the users. Local participation has been one of the most important factors in the association’s impressive success rate in electrifying mountainous regions too isolated for connection to the national grid, as well as in the sustainability of these community projects. Figure A highlights the electricity infrastructure, roadways, and locations of the small-scale and medium-sized hydroelectric generation plants developed by ATDER-BL.

The small-scale hydroelectric plants developed in the communities highlighted on the map – for example in Los Condega, Las Brisas and San Antonio – are highly participatory and transparent. Community members build consensus around a project plan, which includes calculating the necessary hours of labour and financial contributions, determining the site for the generator house, and defining the roles of the project’s organising and governing body. This body, the ‘junta directiva’, is a group of elected representatives who do the administrative and managerial work on behalf of the community. The junta is comprised of six or seven members who voluntarily take on roles that include president, operator, fund manager/treasurer, record keeper/secretary, assembly organiser and communications/administration.

An important role for the junta and a foundation for the project is the building of relationships and trust between community members. Mutually respectful relationships are an important part of the dynamics around community organising in El Cua, and they must continually be monitored in order to ensure that participation is open to everyone. There is one general assembly every six months for all members of the community, and the junta meets every three months (depending on necessity). To ensure that all members are able to participate, the assemblies work around the agricultural cycle and usually include practical discussions about energy usage and plant capacity, materials that need to be purchased, or small maintenance jobs that might require the involvement of more than just the operations person in the junta. Community attendance and engagement in these assemblies is very high, also among youth, women and the elderly.[4]

Collective property ownership and alternative financing

In the case of these micro-hydro electricity plants, the community constructs and owns both the source of generation and the transmission lines that provide them with their electricity. At the outset of the project, it is the community that solicits ATDER-BL. Next, while the community comes together to generate interest and identify funding possibilities, ATDER-BL conducts feasibility studies for a potential site. The contributions made by community members to the fund can be paid either through monetary contributions or with labour. The funds collected by the community are then added to the other funding procured by ATDER-BL for the project. In most cases, this external funding is either a donation or loan agreement with the municipal or national government, or an international donation. The fund is initially administered by ATDER-BL during the construction phase of the project and is used to buy materials, build machinery, pay workers and train community members.

After the project has been constructed, control and management of the fund is transferred to the community members elected to the junta. Contributions are collected annually in order to cover projected expenses and general re-investments. The amount collected is intended to be affordable for residents, and can be paid at once for the entire year or in monthly instalments. Moreover, community members do not pay per kWh as is customary in most energy provision arrangements, as in this case electricity is not simply a commodity being sold to customers. Everyone has a right to this service, and they all pitch in to take responsibility for its provision. Since water runs freely in the river that was partially re-routed to generate electricity, the source of the electricity is also free and energy costs are generally low. For example, fees were collected from all community members – approximately 64 households – in 2016. The contribution amounted to an average of $US67 per household for that year. Yet not all community members pay the same amount into the fund; people who make more money are expected to pay slightly more than those who make less. From one year to the next, the crops of some farmers fare better than others, and as a result some make more money at market and are in a better position to contribute than others. Community members do this willingly, as each family is subject to the same risks, and the farmer that pays more one year may contribute less the next. In this equitable model, all families in the community are able to benefit.

Employment

The hydroelectric projects in these communities have created several employment opportunities for both skilled and unskilled local labour. The positions created include machinists, engineers, agronomists, accountants, administrators and various roles involving community leadership. ATDER-BL always prioritises local training, as it is more cost effective and results in better quality work. Their trainings take into account the reality that community members tend to be experienced in the areas of farming, carpentry, masonry and welding, and that people are usually not university educated. In fact, many of the community members involved in the hydroelectric projects have not completed high school. In ATDER-BL’s experience however, not having gone through the formal school system is not an impediment to learning a new skill. Their training focuses on ensuring that teachers are able to identify transferable skills and knowledge sets in the learners, so that they are empowered to absorb new material. These new skills can often be used to create other employment within or outside the community, which in turn benefits the entire community.

Respect for ecology

The approach to hydroelectric development undertaken in these communities respects the important interconnection and dependency of human life upon natural ecosystems. Community members take care to ensure that the project does not contaminate or endanger these ecosystems. Conflicts do however sometimes arise when projects first come together. For instance, projects need to be located near a potential water source, which may be where families live and farmers grow crops. ATDER-BL’s approach to this potential disruption has always been to keep open lines of communication with the community in order to foster mutual respect among people. This tactic has meant that negotiating a compromise is usually not very difficult. The community comes together to discusses the disruption, and those who will be affected are generally provided with financial compensation for any material damage or crop loss. In most cases the farmers are also community members, and will have an incentive to reach consensus as they will also benefit from the electricity produced by the generation unit.

Additionally, ATDER-BL has purchased a great deal of land for protection and conservation in and around the area’s waterways. Some of the jobs created by the association are within the areas of conservation and revitalisation, as ecosystem protection is such an important part of the generation projects. Community members work to keep the groundwater around the plants healthy for the future, and to build skills and capacity about what crops can best be planted where in order to protect the groundwater. In turn, such ecosystem protection helps them to subsist on the same land year after year.

Current and future plans

ATDER-BL continues to focus on providing opportunities for underserviced regions in Nicaragua. They were instrumental partners in the recent creation of the Association of Renewables in Nicaragua (RENOVABLES), and continue to work in solidarity with a number of local and international partners such as the National Network of Actors for Renewables (RENACER) and the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNI) among many others. [5] Most recently, ATDER-BL has begun to expand its capacity to include the installation of solar power in communities that lack access to energy and are not situated near a water source sufficient for hydro generation. The demand for projects is constantly growing, and there are always communities seeking access to energy. In 2016, ATDER-BL successfully installed 350 solar panels around the watershed in El Bote for dispersed farms far from a significant source of water. However, some 1800 people still live without electricity just outside of the town of El Cua. ATDER-BL hopes to be able to mobilise both national and international funding and support for projects there, and to install a similar number of installations throughout 2018 in other remote areas of the northern highlands. This strategy has proven successful in alleviating persistent energy poverty in the region.

References

- [1] Wikipedia (2017) Biography of Ben Linder Accessed: October 30

- [2] Butler, Judy (1994) Ben Linder’s Dream: Electricity Comes to Bocay Envío 156:1, July

- [3] ATDER-BL (2017) http://www.atder-bl.org/Projects.html Accessed: October 30

- [4] Colbert, M’Lisa (2017) Democratizing Energy in a Marketized World: The Cases of Costa Rica and Nicaragua Queens University, Thesis

- [5] RENOVABLES (2017) http://www.renovables.org.ni/quienes-somos/Nuestra-Historia/ Accessed: October 30