Generals to the dustbin, Algeria will be independent The New Algerian Revolution as a Fanonian moment

Topics

Regions

Six decades after the death of the revolutionary thinker Frantz Fanon and the publication of his masterpiece The Wretched of the Earth, Algeria is witnessing another revolution, this time against the national bourgeoisie that Fanon railed against in his passionate and ferocious chapter ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness’. What would he say about the new Algerian revolution? How might he act in the face of current events? What can we as young Algerians learn from his reflections and experiences?

Hamza Hamouchene

This long read, based on a chapter in the upcoming book ‘Fanon Today: The Revolt and Reason of the Wretched of the Earth’ (Edited by Nigel Gibson, Daraja Press 2021) is an attempt to analyse the 2019-2021 Algerian uprising through a Fanonian lens, trying in this way to shine a light on Fanon’s genius, the timeliness of his analysis, the lasting value of his critical insights and the centrality of his decolonial thought in the revolutionary endeavours of the wretched of the earth.

During the upheavals that the North African and West Asian region witnessed a decade ago (2010-2011) – what has been dubbed the “Arab Spring” – , Fanon’s thought and praxis proved to be as relevant as ever. Not only relevant, but insightful to the extent that they have helped us to grasp the violence of the Manichean world we live in, and the rationality of revolt against it.

Fanon’s writings took place in a period of decolonisation of countries in Africa and elsewhere in the global South. Born Martinican, Algerian by choice, he wrote from the vantage point of the Algerian revolution against French colonialism and of his political experiences on the African continent. One might ask, can his analyses transcend the limitations of time? Can they be universal or impregnated with universalist tendencies? Can we learn from him as a committed intellectual and revolutionary thinker? Or should we just reduce him to another anti-colonial figure, largely irrelevant for our “post-colonial” times?

For me, as a young Algerian activist, Fanon’s dynamic and revolutionary thinking, always about creation, movement and becoming, remains utterly prophetic, vivid, inspiring, analytically sharp and morally committed to disalienation and emancipation from all forms of oppression. He strongly and compellingly argued for a path to a future where humanity ‘advances a step further’ and breaks away from the world of colonialism and European universalism. In another way, he represented the maturing of the anti-colonial consciousness and was a decolonial thinker par excellence. As a true embodiment of ‘l’intellectuel engagé’, he has transformed the debate on race, colonialism, imperialism, otherness and what it means for one human being to oppress another.

Despite his short life (he died at the age of 36 from leukaemia), Fanon’s thought is very rich and his work was prolific from books and papers to speeches. He wrote his first book Black Skin, White Masks (Fanon, 1986) two years before Dien Bien Phu (1954) and his last book, the famous The Wretched of the Earth (Fanon, 1967a), a canonical essay about the anti-colonialist and third-worldist struggle, one year before Algerian independence (1962), at a moment when African countries were gaining their independence. In his trajectory, we can see the interactions between Black America and Africa, between the intellectual and the militant, between thought/theory and action/practice, between idealism and pragmatism, between individual analysis and collective movement, between the psychological life (he trained as a psychiatrist) and the physical struggle, between nationalism and Pan-Africanism and finally between questions of colonialism and those of neo-colonialism (Bouamama, 2017, p140-159).

Fanon died less than a year before Algeria got its independence on July 5, 1962. He did not live to see his adoptive country become free from French colonial domination, something he believed had become inevitable. This radical intellectual and revolutionary devoted himself, body and soul to the Algerian national liberation. His experience and analysis was the prism through which many revolutionaries abroad understood Algeria and helped to make the country synonymous with Third World revolution. Fanon’s ideas were always influenced by practice and also transformative. They inspired anti-colonial struggles all over the world; shaped Pan-Africanism and profoundly influenced the Black Panthers in the US.

Fanon wrote: ‘Each generation must out of relative obscurity discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it’ (Fanon, 1967a, p166). The challenge is once again being laid down these last few years with an explosion of revolts and uprisings all over the world that includes the second wave of the Arab uprisings from Algeria to Lebanon and from Sudan to Iraq. Six decades after the publication of his masterpiece The Wretched, Algeria is witnessing another revolution, this time against the national bourgeoisie that Fanon railed against in his passionate and ferocious chapter ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness’.

What would he say about the new Algerian revolution? How might he act in the face of current events? What can we as young Algerians learn from his reflections and experiences? This chapter is an attempt to analyse the 2019-2020 Algerian uprising through a Fanonian lens, trying in this way to shine a light on Fanon’s genius, the timeliness of his analysis, the lasting value of his critical insights and the centrality of his decolonial thought in the revolutionary endeavours of the wretched of the earth.

Alice Walker once said: ‘A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children and if necessary, bone by bone’ (Walker, 1983, p92). It is in this spirit that I embark upon this chapter, as Fanon’s theoretical insights and radical praxis have been largely absent from Algerian political thought in the last half century for various reasons that I will delve into.

But before getting there, a little historical detour to the colonial period is needed in order to contextualise Fanon’s thought and to lay the ground for his critiques of the predatory bourgeoisie against which Algerians revolted in 2019/2021.

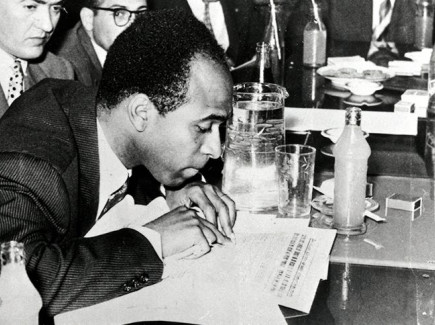

https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-26-fanon/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fanon and colonial Algeria

"

This European opulence is literally scandalous, for it has been founded on slavery, it has been nourished with the blood of slaves and it comes directly from the soil and from the sub-soil of that under-developed world. The well-being and the progress of Europe have been built up with the sweat and the dead bodies of Negroes, Arabs, Indians and the yellow races.

For in a very concrete way, Europe has stuffed herself inordinately with the gold and raw materials of the colonial countries: Latin America, China and Africa. From all these continents, under whose eyes Europe today raises up her tower of opulence, there has flowed out for centuries towards that same Europe diamonds and oil, silk and cotton, wood and exotic products. Europe is literally the creation of the Third World. The wealth which smothers her is that which was stolen from the under-developed peoples.

The Algerian independence struggle against the French colonialists was one of the most inspiring anti-imperialist revolutions of the 20th century. It was part of the decolonization wave that had started after the Second World War in India, China, Cuba, Vietnam and many countries in Africa. It inscribed itself in the spirit of the Bandung Conference and the era of the ‘awakening of the South’, a South that has been subjected for decades (132 years for Algeria) to imperialist and capitalist domination under several forms, from protectorates to settler colonies.

The colonial period can be summarized by expropriations, proletarianization, forced sedentarisation, sheer exploitation and brutal violence. Frantz Fanon described thoroughly the mechanisms of violence put in place by colonialism to subjugate the oppressed people. He wrote: ‘Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state’ (Fanon, 1967a, p48). According to him, the colonial world is a Manichean world, which goes to its logical conclusion and ‘dehumanizes the native, or to speak plainly it turns him into an animal’ (Fanon, 1967a, p32).

What followed the declaration of war of independence on November 1, 1954, was one of the longest and bloodiest wars of decolonization, which saw a massive involvement of the rural poor and urban popular classes (lumpenproletariat). Official estimates claim that a million and half Algerians were killed in the eight-year war that ended in 1962, a war that has become the foundation of modern Algerian politics.

Arriving at Blida psychiatric hospital in 1953, Fanon realised quickly that colonisation, in its essence, was a big producer of madness and hence the necessity of psychiatric hospitals. For him, colonisation was a systematic negation of the other and a frantic refusal of any attribute of humanity to them. In contrast to other forms of domination, the violence here is total, diffuse, permanent and global. Treating both torturers and victims, Fanon couldn’t escape this total violence, which he analysed. This led him to resign in 1956 and join the national liberation front (FLN). He wrote: ‘The Arab, alienated permanently in his country, lives in a state of absolute depersonalisation’. He added that the Algerian war was ‘a logical consequence of an abortive attempt to decerebralise a people’ (Khalfa and Young, 2018, p434). He has been unfairly and wrongly accused of being the prophet of violence. What he did was only describing and analysing the violence of the colonial system.

Fanon saw the colonial ideology being underpinned by the affirmation of white supremacy and its corollary “civilising” mission. The result was the development in the “indigènes évolués” (the “evolved natives”) of a desire to be white, a desire which is nothing more than an existential deviation. However, this desire stumbles upon the unequal character of the colonial system which assigns places according to colour.

In his book Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon analysed the cultural alienation of the colonised/racialised and its reflection in behaviours and identity. He argued that it was the result of enduring domination founded on economic exploitation. Sooner or later, this unsustainable situation unleashes a process of disalienation, resistance and emancipation. Throughout his professional work and militant writings, he challenged the dominant culturalist and racist approaches and discourses on the natives, such as the “North African Syndrome”: Arabs are lazy, liars, deceivers, thieves, etc (Fanon, 1967b, p3-16). He advanced a materialist explanation, situating symptoms, behaviours, self-hatred and inferiority complexes in the life of oppression and the reality of unequal colonial relations. Therefore the solution to these issues was to act in the direction of radically changing social structures.

Fanon had high hopes and strongly believed in revolutionary Algeria. His illuminating book A Dying Colonialism (Fanon, 1965) or as it is known in French L’An Cinq de la Révolution Algérienne, attests to that and shows how liberation does not come as a gift. It is seized by the masses with their own hands and by seizing it they are themselves transformed. He strongly argued that, for the masses, the most elevated form of culture – that is to say, of progress – is to resist imperialist domination and penetration. For Fanon, revolution is a transformative process that will create ‘new souls’.1 For this reason Fanon closes his 1959 book with the words: ‘The revolution in depth, the true one, precisely because it changes man and renews society, has reached an advanced stage. This oxygen which creates and shapes a new humanity – this, too, is the Algerian revolution’ (Fanon, 1965, p181).

Pixabay Content License

Independence period: Bankruptcy of the ‘postcolonial’ ruling elites

Unfortunately, the Algerian revolution and its attempt to break from the imperialist-capitalist system were defeated, both by counter-revolutionary forces and by its own contradictions. The revolution harboured the seeds of its own failure from the start: it was a top-down, authoritarian, and highly bureaucratic project (albeit with some redistributive functions that significantly improved people’s lives). For example, the creative experiences of workers’ initiatives and self-management of the 1960s and 1970s were undermined by a paralyzing state bureaucracy that failed to genuinely involve workers in the control of the processes of production. This lack of democracy was concomitant with the ascendancy of a comprador bourgeoisie that was hostile to socialism and staunchly opposed to genuine land reform (Bennoune, 1988). By the 1980s, the global neoliberal counter-revolution was the nail in the coffin and ushered in an age of deindustrialization and pro-market policies in Algeria, at the expense of the popular strata. The dignitaries of the new neoliberal orthodoxy declared that everything was for sale and opened the way for mass privatization.

Fanon’s work, written six decades ago still bears a prophetic power as an accurate description of what happened in Algeria and elsewhere. Reading Fanon’s words and especially ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness,’ one cannot help being absorbed and shaken by their truth and foresight. Fanon foretold the bankruptcy and sterility of national bourgeoisies in Africa and the Middle East today; bourgeoisies that tended to replace the colonial force with a new class-based system replicating the old colonial structures of exploitation and oppression.

By the 1980s, the Algerian national bourgeoisie, like those in other parts of the world, had dispensed with popular legitimacy, turned its back on the realities of poverty and underdevelopment, and was only preoccupied with filling its own pockets and exporting the enormous profits it derived from the exploitation of its people. In Fanon’s terms, this parasitic and unproductive bourgeoisie (civilian and military) has had the upper hand in running state affairs and directing economic decisions for its own interests. This elite is the biggest threat to the sovereignty of the nation as it is selling off the economy to foreign capitals and multinationals and cooperating with imperialism in its ‘war on terror’, another pretext for expanding the domination of the people and the scramble for resources. In Algeria, this national bourgeoisie, closely connected to the ruling party, the FLN, renounced the autonomous development project initiated in the 1960s and 1970s and did not even bargain for concessions from the West, which would have been of value for the country’s economy. Instead, it offered one concession after another for blind privatizations and projects that would undermine the country’s sovereignty and endanger its population and environment — the exploitation of shale gas and offshore resources being just one example (Hamouchene and Rouabah, 2016).

This is what has become of Algeria today, with oil money used to buy social peace2 as well as to strengthen the state’s repressive apparatus, corresponding to what Fanon feared. That his vision and truth telling were – and remain – unpopular with the ruling class is one reason why he is marginalised today and reduced to just another anti-colonial figure, stripped of his incandescent attack on the stupidity and on the intellectual and spiritual poverty of the national bourgeoisies.

As Edward Said argued, the true prophetic genius of The Wretched of the Earth is when Fanon senses the divide between the nationalist bourgeoisie and the FLN’s liberationist tendencies. He realised that orthodox nationalism followed ‘the same track hewn out by imperialism, which while it appeared to concede authority to the nationalist bourgeoisie was really extending its hegemony’ (Said, 1994).

Today, Algeria – but also Tunisia, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, Gabon, Angola and South Africa, among others – follows the dictates of the new instruments of imperialism such as the IMF, the World Bank and negotiates entry into the World Trade Organisation. Some African countries are still using the CFA franc (renamed Eco in December 2019), a currency inherited from the times of colonialism and still under the control of the French Treasury. Fanon would have been revolted at this bêtise and sheer mindlessness.

He predicted this dire situation and the shocking behaviour of the national bourgeoisie when he noted that its mission has nothing to do with transforming the nation but rather consists of ‘being the transmission line between the nation and capitalism, rampant though camouflaged, which today puts on the masque of neo-colonialism’ (Fanon, 1967a, p122). This is where we can appreciate the lasting value of employing Fanon’s critical insights when he introduces the question of social classes and describes for us the contemporary postcolonial reality, a reality shaped by neo-colonialism and a national bourgeoisie ‘unabashedly…anti-national,’ opting he adds, for an abhorrent path of a conventional bourgeoisie, ‘a bourgeoisie which is stupidly, contemptibly and cynically bourgeois’ (Fanon, 1967a, p121).

Fanon would have been shocked by the ongoing international division of labour, where we Africans ‘still export raw materials and continue ‘being Europe’s small farmers who specialise in unfinished products’ (Fanon, 1967a, p122). The ruling classes in Algeria have trapped the country in a predatory extractivist model of development where profits are accumulated in the hands of a foreign-backed minority at the expense of dispossession of the majority of the population (Hamouchene, 2019).

Riad Kaced

Rationality of Rebellion: The Hirak and the new Algerian revolution

The sad contemporary reality that Fanon described and warned against six decades ago gives little doubt that, were he alive today, Fanon would be hugely disappointed at the result of his efforts and those of other revolutionaries. He turned out to be right about the rapacity and divisiveness of national bourgeoisies and the limits of conventional nationalism.

However, Fanon alerts us that the scandalous enrichment of this profiteering caste will be accompanied by ‘a decisive awakening on the part of the people and a growing awareness that promised stormy days to come’ (Fanon, 1967a, p134). So we can see Fanon’s idea or concept of the rationality of revolt and rebellion was made clear by the second wave of the Arab uprisings and other mass protests around the world in 2019-2021. The popular masses in all these countries rebelled against the violence of the political regimes that offered them growing pauperisation, marginalisation and the enrichment of the few at the expense and damnation of the majority.

Algerians shattered the wall of fear and broke away from an alienation process that had infantilised and dazed them for decades. They erupted onto the political scene, discovered their political will and began again to make history. Since Friday February 22, 2019, millions of people, young and old, men and women from different social classes rose in a momentous rebellion. Historic Friday marches, followed by protests in professional sectors, united people in their rejection of the ruling system and their demands of radical democratic change. ‘They must all go!’ (Yetnahaw ga’), ‘The country is ours and we’ll do what we wish’ (Lablad abladna oundirou rayna), two emblematic slogans of this so-far peaceful uprising, symbolise the radical evolution of this popular movement (Al Hirak Acha’bi). The uprising was triggered by the incumbent president Bouteflika’s announcement that he would run for a fifth term despite being impotent, suffering from aphasia and being generally absent from public life.

The people in Algeria revolted not only to demand democracy and freedom but also to demand bread and dignity, against the oppressive socio-economic conditions under which they had lived for decades. They rose up to challenge the Manichean geographies of oppressor and oppressed (so well described by Fanon in The Wretched), geographies imposed on them by the globalised capitalist-imperialist system and its local lackeys.

The events taking place in Algeria during 2019-2021 are truly historic. This movement (Hirak) is unique is its huge scale, peaceful character, national spread – including in the marginalised south, and massive participation from women and young people, who constitute the majority of Algeria’s population. This kind of mobilization has not been seen since 1962, when Algerians went to the streets to celebrate their hard-won independence from French colonial rule.

This revolution is like a breath of fresh air. The people have affirmed their role as agents of their own destiny. We can use Fanon’s exact words to describe this phenomenon: ‘The thesis that men change at the same time that they change the world has never been manifest as it is now in Algeria. This trial of strength not only remodels the consciousness that man has of himself, and of his former dominators or of the world, at last within his reach. The struggle at different levels renews the symbols, the myths, the beliefs, the emotional responsiveness of the people. We witness in Algeria man’s reassertion of his capacity to progress’ (Fanon, 1965, p30).

Perhaps one of the greatest achievements of the current popular uprising is the change in political consciousness and the determination to fight for radical democratic change. This liberatory process unleashed an unequalled amount of energy, confidence, creativity and subversion.

After decades of curtailed civil society, silenced dissent, and atomized opposition, the fact that the movement grew from strength to strength for more than a year, not retreating or subsiding but pushing forward, is truly remarkable and inspiring. The Hirak succeeded in unravelling the webs of deceit that were deployed by the ruling class and its propaganda machine. Moreover, the evolution of its slogans, chants, and forms of resistance, is demonstrative of processes of politicization and popular education. The re-appropriation of public spaces created a kind of an agora where people discuss, debate, exchange views, talk strategy and perspectives, criticize each other or simply express themselves in many ways including through art and music. This has opened new horizons for resisting and building together.

Cultural production took on another meaning because it was associated with liberation and seen as a form of political action and solidarity. Far from the folkloric and sterile productions under the suffocating patronage of some authoritarian elites, we are seeing instead a culture that speaks to the people and advances their resistance and struggles through poetry, music, theatre, cartoons, and street-art. Again, we see Fanon’s insights in his theorization of culture as a form of political action: ‘A national culture is not a folklore, nor an abstract populism that believes it can discover the people’s true nature. It is not made up of the inert dregs of gratuitous actions, that is to say actions which are less and less attached to the ever-present reality of the people… It is around the people’s struggles that African-Negro culture takes on substance and not around songs, poems or folklore’ (Fanon, 1967a, p188-189).

Photo: Riad Kaced

The struggle of decolonisation continues

"

Many colonised people have demanded the end of colonialism, but rarely like the Algerian people.

Leaving aside largely semantic arguments around whether it is a movement, uprising, revolt or a revolution, one can say for certain that what is taking place in Algeria today is a transformative process, pregnant with emancipatory potential. The evolution of the movement and its demands specifically around ‘independence’, ‘sovereignty’ and ‘an end to the pillage of the country’s resources’ are fertile ground for anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and even ecological ideas. This can open the way for a progressive struggle by mobilizing the relevant social forces: workers (formal and informal), peasants, unemployed youth, popular masses, etc.

Algerians are making a direct link between their current struggle and the anti-French colonial struggle of the 1950s, seeing their efforts as the continuation of decolonization. When chanting ‘Generals to the dustbin and Algeria will be independent’, they are laying bare the vacuous official narrative around the glorious revolution and revealing that it has been shamelessly used by anti-national bourgeoisies to scandalously pursue personal enrichment. This is undoubtedly a second Fanonian moment where people expose the neo-colonial situation they find their country in and emphasise one unique characteristic of their uprising: its rootedness in the anti-colonial struggle against the French.

Algerians are thus recovering their revolutionary credentials and reaffirming their desire to be the true heirs of the martyrs who sacrificed their lives for the liberation of this country. Slogans and chants have captured this desire and made references to anti-colonial war veterans such as Ali La Pointe, Amirouche, Ben Mhidi and Abane: ‘Oh Ali [la pointe] your descendants will never stop until they wrench their freedom!’ and ‘We are the descendants of Amirouche and we will never go back!’

It becomes clear that the colonialism which Fanon analysed six decades earlier has not entirely disappeared. Instead it has metamorphosed, camouflaging itself in sophisticated forms and mechanisms: debt; structural adjustment programmes; ‘free trade’ treaties; association agreements with the EU; predatory extractivism; land grabs; agribusiness; immigration laws and deadly borders; ‘humanitarian’ intervention and the responsibility to protect; international cooperation and development; racism and xenophobia; etc. All these constitute forms of domination and control deployed to safeguard the interests of the powerful.

The struggle of decolonization is being given a new lease of life as Algerians lay claim to the popular and economic sovereignty that was denied to them when formal independence was achieved in 1962. Fanon had a premonition about this when he wrote: ‘The people who at the beginning of the struggle had adopted the primitive Manichaeism of the settler – Blacks and Whites, Arabs and Christians – realise as they go along that it sometimes happens that you get Blacks who are whiter than the Whites and the hope of an independent nation does not always tempt certain strata of the populations to give up their interests or privileges’ (Fanon, 1967a, p115).

Hamza Hamouchene

Counter-revolution: the reactionary role of the army

As with any revolution, counter-revolutionary forces have mobilized to block change. The counter-revolutionary campaign currently underway in Algeria draws support from abroad. Regionally, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Egypt are using their money and influence to halt potentially contagious waves of revolt in the region. At the global level, France, the US, UK, Canada, Russia and China, along with their major corporations, seeing a potential threat to their economic and geostrategic interests, are all supportive of the Algerian regime.

Times of revolutions and uprisings can also be times of entrenching unpopular economic policies and extending more concessions to foreign investors. The budget law of 2020 and the new multinational-friendly Hydrocarbon Law are illustrative (Rouabah, 2019). We cannot therefore fully appreciate the political situation in Algeria without scrutinizing foreign influences and interferences and apprehending the economic question from the angle of natural resource grabs, energy (neo)colonialism and extractivism (Hamouchene, 2019).

When it comes to the political level, the counter-revolution has been embodied by the military hierarchy. The army has not fired any bullets so far, but it has continued to justify various repressive measures. Since independence in 1962, Algeria has been ruled by a military regime, directly or indirectly. The militarization of society has created a culture of fear and distrust. The brutal repression of past uprisings and the cruelty of the war in the 1990s explain the popular movement’s reluctance to directly confront the army.

The military bourgeoisie still proclaims that the ‘vocation of their people is to obey, to go on obeying and to be obedient till the end of time’ (Fanon, 1967a, p135) and as Fanon castigated it, it’s an army that ‘pins the people down, immobilizing and terrorizing them’ (Fanon, 1967a, p140). However, despite the Military High Command’s rejection of every roadmap and appeal for genuine dialogue proposed by the movement, people remain determined to peacefully demilitarize their republic. They have been chanting: ‘A republic not a military barrack’. After Bouteflika’s overthrow, demonstrations continued in opposition to the military, which has maintained de facto authority over the country.

In these poor, under-developed countries, where the rule is that the greatest wealth is surrounded by the greatest poverty, the army and the police constitute the pillars of the regime; an army and a police force which are advised by foreign experts. The strength of the police and the power of the army are proportionate to the stagnation in which the rest of the nation is sunk. By dint of yearly loans, concessions are snatched up by foreigners; scandals are numerous, ministers grow rich, their wives doll themselves up, the members of parliament feather their nests and there is not a soul down to the simple policeman or the customs officer who does not join in the great procession of corruption.

This raging passage from The Wretched is a fairly accurate portrayal of the situation in Algeria and many African countries where repression and suppression of freedoms are the rule – helped of course by foreign expertise – and where greedy elites institutionalise corruption and serve foreign interests. One of the emblematic slogans of the current uprising has been very eloquent in this regard: ‘You devoured the country…Oh you thieves!’

Algerians know what the military are capable of and despite the trauma of the ‘black decade’ (civil war of the 1990s), they are bravely still insisting: ‘A civilian state not a military one!’. In this way, the Algerian system is exposed for what it is: a military dictatorship hiding behind a ‘democratic’ façade.

Class struggle, organising and political education

"

In a short time this continent will be liberated. For my part, the deeper I enter into the cultures and the political circles the surer I am that the great danger that threatens Africa is the absence of ideology.

All this taking stock of the situation, this enlightening of consciousness and this advance in the knowledge of the history of societies are only possible within the framework of an organization and inside the structure of a people.

Despite the odds stacked against it, and the state’s efforts to divide, co-opt, and exhaust it, the Hirak has maintained an exemplary unity and peacefulness. This was demonstrated in various slogans such as: ‘Algerians are brothers and sisters, the people are united, you traitors.’

The movement is youth-led and relatively loosely organised. There are no clearly identifiable leaders or organised structures propelling it. It is a popular uprising mobilising mass forces from the middle classes and from the marginalised classes in urban and rural areas. Unlike Sudan, where the Sudanese Professional Association played a leading and organising role, in Algeria organising is done horizontally and mainly through social media. The general strike in the first few weeks of the uprising, which was instrumental in forcing Bouteflika to abdicate and shaking up alliances within the ruling class, was organised spontaneously after anonymous calls on social media. Such amorphous, non-structured and leaderless dynamics and movements are extremely vulnerable. While they can generate large inter-class mobilisations and are not an easy target for repression, or for co-option of leaders, they nevertheless manifest fatal weaknesses in the long run.

But, what can Fanon teach us when it comes to the class struggle and organising?

Class struggle is central to Fanon’s analysis. The Lebanese Marxist, Mahdi Amel, pointing to Fanon’s insights on how the revolutionary praxis differentiates and changes its meaning and direction after independence, writes: ‘While it [revolutionary violence] was before independence, essentially a national struggle, after independence it becomes a real class struggle’ through which the masses discover their true enemy: the national bourgeoisie (Hamdan, 1964a). So from a strictly national level, the fight moves to a socio-economic level of class struggle. Fanon urges us to move from a national consciousness towards a social and political consciousness when he says, ‘If nationalism is not made explicit, if it is not enriched and deepened by a very rapid transformation into a consciousness of social and political needs, in other words into humanism, it leads up a blind alley’ (Fanon, 1967a, p165).

However, Fanon invites us to ‘stretch Marxism’ as a way of understanding the particularities of capitalism in the colonial and postcolonial world. To borrow Immanuel Wallerstein’s words, Fanon ‘had rebelled, forcefully, against the ossified Marxism of the communist movements of his era’, asserting a revised version of the class struggle breaking with the dogma that the urban, industrial proletariat is the only revolutionary class against the bourgeoisie (Wallerstein, 2009). Fanon thought of the peasantry and the urbanized lumpenproletariat as the strongest candidate for the role of historical revolutionary subject in colonial Algeria. And here, Fanon meets Che Guevara when both point out that in colonised countries, revolution begins in rural areas and moves to the urban towns. It is launched by the peasantry, which embraces the proletariat rather than the other way around as in the case of European capitalist, and even socialist, countries (Hamdan, 1964b).

In a nutshell, class struggle is essential provided we clearly identify the struggling classes. In this spirit, it’s crucial to determine the revolutionary classes (and their alliances) in the current uprising. We need to go beyond ‘workerism’ and embrace a much broader conception of the proletariat in its contemporary expressions, namely the unemployed youth, the urban/rural working people, informal workers, peasants, etc. It is these classes that have nothing to lose but their chains, which makes them potentially revolutionary.

In his chapter ‘Spontaneity: its strengths and weaknesses’ in The Wretched, Fanon expressed concerns that if the lumpen-proletariat is left on its own, without organisational structure, it will burn out (Wallerstein, 2009). In order to avoid this and to bar the route against the parasitic bourgeoisie that is still ruling in Algeria, Fanon would probably say: ‘The bourgeoisie should not be allowed to find the conditions necessary for its existence and its growth. In other words, the combined effort of the masses led by a party and of intellectuals who are highly conscious and armed with revolutionary principles ought to bar the way to this useless and harmful middle class’ (Fanon, 1967a, p140).

Fanon would also repeat to us an important observation he made on some African revolutions, which is that their unifying character sidelines any thinking of a socio-political ideology on how to radically transform society. This is a great weakness that we are witnessing yet again with the new Algerian revolution. ‘Nationalism is not a political doctrine, nor a programme’, says Fanon (Ibid, p163). He insists on the necessity of a revolutionary political party (or perhaps an organised social movement) that can take the demands of the masses forward, a party/structure that will educate the people politically, that will be ‘a tool in the hands of the people’ and that will be the energetic spokesman and the ‘incorruptible defender of the masses.’ For Fanon, reaching such a conception of a party necessitates first of all ridding ourselves of the bourgeois notion of elitism and ‘the contemptuous attitude that the masses are incapable of governing themselves’ (Ibid, p151).

Fanon abhorred the elitist discourse on the immaturity of the masses and asserted that in the struggle, they (the masses) are equal to the problems which confront them. It is therefore important for them to know just where they are going and why. Nigel Gibson eloquently articulated this view in these words: ‘for Fanon, the “we” was always a creative “we”, a “we” of political action and praxis, thinking and reasoning’ (Gibson, 2011). For him, the nation does not exist except in a socio-political and economic program ‘worked out by revolutionary leaders and taken up with full understanding and enthusiasm by the masses’ (Fanon, 1967a, p164).

Unfortunately, what we see today in Africa is the antithesis of what Fanon strongly argued for. We see the stupidity of the anti-democratic bourgeoisies embodied in their tribal and family dictatorships, banning the people, often with crude force, from participating in their country’s development, and fostering a climate of immense hostility between the rulers and the ruled. Fanon, in his conclusion of The Wretched, argues that we have to work out new concepts through ongoing political education, enriched through mass struggle. Political education for him is not merely about political speeches but rather about ‘opening the minds’ of the people, ‘awakening them, and allowing the birth of their intelligence’ (Ibid, p159). ‘If building a bridge does not enrich the awareness of those who work on it’, then according to Fanon, it ‘ought not to be built and the citizens can go on swimming across the river or going by boat’ (Ibid, p162).

This is perhaps one of the greatest legacies of Fanon. His radical and generous vision is so refreshing and rooted in the people’s daily struggles, which open up spaces for new ideas and imaginings. For him, everything depends on the masses, hence his idea of radical intellectuals engaged in and with people’s movements and capable of coming up with new concepts in non-technical and non-professional language. Just as, for Fanon, culture has to become a fighting culture, so too must education become about total liberation (Gibson, 2011). This is what we need to bear in mind when we talk about education in schools and universities. Decolonial education in the Fanonian sense is an education that helps create a social and political consciousness. The militant or the intellectual, therefore, must not take shortcuts in the name of getting things done, as this is inhuman and sterile. It is all about coming and thinking together, which is the foundation of the liberated society.

Pixabay Content License

The shadow of Fanon: the new Algerian revolution and Black Lives Matter

"

We are off. Our mission: to open the southern front. To transport arms and munitions from Bamako. Stir up the Saharan population, infiltrate to the Algerian high plateaus. After carrying Algeria to the four corners of Africa, move up with all Africa toward African Algeria, toward the North, toward Algiers, the continental city … Subdue the desert, deny it, assemble Africa, create the continent.

In 2020, a global revolt against white supremacy started in the streets of Minneapolis in the United States following the murder of George Floyd, a 46 year-old Black man by a policeman who knelt with his knee on his neck for almost 8 minutes. Like Eric Garner before him, George Floyd uttered these last words before he died: ‘I can’t breathe’. The ensuing global rebellion and show of solidarity echo the words of Fanon when he discussed the Vietnamese anti-colonial struggle: ‘It is not because the Indo-Chinese has discovered a culture of his own that he is in revolt. It is because “quite simply” it was, in more than one way, becoming impossible for him to breathe’ (Fanon, 1986, p176).

We can no longer breathe in a system that dehumanises people, a system that enshrines super-exploitation, a system that dominates nature and humanity, a system that generates massive inequality and untold poverty. Luckily, revolts that are fundamentally anti-systemic are taking place on all continents and regions. But for these episodic and largely geographically-confined acts of resistance to succeed, they need to go beyond the local to the global; they need to create enduring alliances in face of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy.

Can these various contemporary struggles, from the Arab uprisings to Black Lives Matter, converge and build strong alliances that overcome their own contradictions and blind spots? Can they usher in a new moment where we question the colonial foundations of our current predicaments and continue on the path of decolonising our politics, economies, cultures and epistemologies? This is not only possible but necessary as we must envisage such transnational solidarities and alliances because they are crucial in the global struggle of emancipation of the wretched of the earth. Perhaps, we can take inspiration from the past, by looking at the decolonisation period, Bandung and Third- Worldism era, the Tri-Continental and other internationalist experiences. I would argue that Fanon (or more accurately his intellectual legacy) could be once again the linkage and the nodal point of these struggles, like he was in the 1960s and 1970s.

Some histories are ignored, others are silenced in order to maintain certain hegemonies and to hide from view an inspiring era of revolutionary connections between struggles for liberation on different continents. We must dig into this past to familiarise ourselves with these histories, learn from them and discern some potential convergences between ongoing struggles.

In the first two decades of its independence, Algeria became, as Samir Meghelli described it, ‘a critical node in the constellation of transnational solidarities’ being forged among revolutionary movements around the world (Meghelli, 2009). In the heydays of the Civil Rights and Black Power eras, Meghelli shows that ‘just as Algeria looked to Black America as “that part of the Third World situated in the belly of the beast” (Neal, 1966) so, too, did much of Black America look to Algeria as “the country that fought the enslaver and won”’ (Joans, 1970).

Algeria became a powerful symbol of revolutionary struggle and served as a model for several liberation fronts across the globe. And given its audacious foreign policy in the 1960s and 1970s, the Algerian capital was to become a Mecca for all revolutionaries. As Amilcar Cabral, the revolutionary leader from Guinea-Bissau announced at a press conference at the margins of the first Pan-African festival in 1969: ‘Pick a pen and take note: the Muslims make the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Christians to the Vatican and the national liberation movements to Algiers!’

Thanks to the popular film The Battle of Algiers as well as Frantz Fanon’s writings, Algeria came to hold an important place in the ‘iconography, rhetoric, and ideology of key branches of the African American freedom movement’ (Meghelli, 2009), which came to view their struggle for civil rights as connected to the struggles of African nations for independence. Francee Covington, a student in political science at Harlem University in the late 1960s made this point even clearer: ‘In the past few years the works of Frantz Fanon have become widely read and quoted by those involved in the “Revolution” that has begun to take place in the communities of Black America. If The Wretched of the Earth is the “handbook for the Black Revolution,” then The Battle of Algiers is its movie counterpart’ (Covington, 1970, p245).

The writings of Fanon and his analysis of the Algerian war revealed so many parallels between the experience of colonial domination in Algeria and the racial oppression Blacks had suffered for centuries in America. His book The Wretched had become a ‘Black bible’ to use the words of Eldridge Cleaver. By the end of the 1970s, it had sold some 750,000 copies in the United States. This led Dan Watts, editor of Liberator magazine to say: ‘Every brother on a rooftop can quote Fanon’ (Zolberg and Zolberg, 1970, p198).

In his visit to New York on October 1962, Ahmed Ben Bella, one of the FLN leaders and the first Algerian president, met with Dr Martin Luther King Jr. and made it clear that there is a close relationship between colonialism and segregation (King, 1962). This view advocating for a global perspective on oppression (be it either colonial or racist) was expressed a few years later by Malcolm X. After visiting Algeria in 1964 and the Casbah – the site of the battle of Algiers against French militaries in 1957 – and after responding to the allegations that there existed some sort of “hate-gang” called the “Blood Brothers” based in Harlem and calculatedly committing crimes against whites, he declared at the militant Labour Forum: ‘The same conditions that prevailed in Algeria that forced the people, the noble people of Algeria, to resort eventually to the terrorist-type tactics that were necessary to get the monkey off their backs, those same conditions prevail today in America in every Black community’ (Meghelli, 2009).

It is this global perspective on our struggles that we need to emphasise in order to break away from the many constraints and limitations imposed on our movements in order to embrace a radical internationalism that will actively promote solidarity. Therefore it becomes essential to rediscover the revolutionary heritage of the Maghreb, Africa, West Asia and the Global South, developed by great minds like Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, Thomas Sankara, Walter Rodney and Samir Amin to mention just a few. We need to revive the ambitious projects of the 1960s that sought emancipation from the imperialist-capitalist system. Building on this revolutionary heritage, being inspired by its insurgent hope and applying its internationalist perspective to the current context is of utmost importance to Algeria, to the Black Lives Matter movement and to other emancipatory struggles all over the world.

Photo: Riad Kaced

In guise of conclusion

The progressive forces in Algeria and beyond have a huge task confronting them: the task of putting the socio-economic issue at the centre of the debate around alternatives and injecting a class analysis into the broad movement. It is incumbent upon them, and more specifically upon the radical and revolutionary left, to elaborate new visions that go beyond resistance to the current predatory offensive of capitalism to question the imaginary of development and modernity itself, an imaginary that means we get incorporated into a lifestyle based on overconsumption and inserted into globalisation in a subordinate position.

Fanon urged us to invent and make new discoveries and not blindly imitate Europe. The struggle of decolonisation, Fanon tells us, must challenge the dominance of European culture and its claims of universalism without being trapped in a romanticized and fixed past. It is these two alienations that colonised people must overcome in their cultural struggle. Decolonising the mind also means deconstructing Western notions of ‘development’, ‘civilisation’, ‘progress’, ‘universalism’ and ‘modernity’.

Such concepts represent what is called a coloniality of power and knowledge, which means that ideas of ‘modernity’ and ‘progress’ were conceived in Europe and North America and then implanted in our continents (Africa, Asia and Latin America) in a context of coloniality (Mignolo, 2012). These Eurocentric ideas and culture have reinforced the colonial heritage of land confiscations, resource plunder, as well as domination of ‘other’ peoples in order to ‘civilise’ them.

These notions (‘progress’, ‘development’, ‘modernity’…) are imposed notions and are based on a linear conception of the evolution of history that divides the world between ‘developed’ and ‘under-developed’; ‘advanced’ and ‘less advanced’; ‘modern’ (read Western) and ‘backward’ (read non-Western). They are concepts that pretend to be universal and issue injunctions to the excluded and dispossessed to follow a pre-determined path in order to enter an imperial and colonial globalisation, led by the ‘advanced’ countries, legitimising therefore their subordination. Being Eurocentric, these concepts assert their self-claimed superiority by excluding and delegitimizing other forms of knowledge, other ways of life and other civilisations’ contributions (Gudynas, 2013).

Fanon did not offer us a clear prescription for making the transition after decolonisation to a new liberating political order. Perhaps, there is no such thing as a detailed plan or solution. Perhaps he viewed it as a protracted process that will be informed by praxis and, above all, by confidence in the masses and in their revolutionary potential to figure out the liberating alternative.

In the conclusion of The Wretched, Fanon wrote:

Come, then, comrades; it would be as well to decide at once to change our ways. We must shake off the heavy darkness in which we were plunged, and leave it behind. The new day which is already at hand must find us firm, prudent and resolute…. Let us waste no time in sterile litanies and nauseating mimicry. Leave this Europe where they are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of every one of their own streets, in all the corners of the globe… Come, then, comrades, the European game has finally ended; we must find something different. We today can do everything, so long as we do not imitate Europe, so long as we are not obsessed by the desire to catch up with Europe…. For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must turn over a new leaf, we must work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man.

In this vein, it is paramount to continue the tasks of decolonisation and delinking from the imperialist-capitalist system in order to restore our denied humanity. Through resistance to colonial and capitalist logics of appropriation and extraction, new imaginaries and counter-hegemonic alternatives will be born.