Green Industrial Policy in Asia Pacific and the Global Supply Chain A Dynamic Exchange of Ideas for a Sustainable Future

Topics

Regions

The Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Institute (STIPI) at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT), in collaboration with the Transnational Institute (TNI), the GreenPaths project, the GRIP-ARM project, and the University of Sussex, co-organised the international workshop titled Green Industrial Policy in Asia Pacific and the Global Supply Chain: A Dynamic Exchange of Ideas for a Sustainable Future. The workshop was held in Bangkok from 21–23 May 2025, and in this article we share its main discussions and outcomes.

The resurgence of industrial policy in mainstream economic debates occurs within the broader context of multiple crises (Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik 2024; Nem Singh 2023). In East Asia, the role of industrial policy has historically been documented as a means for national industrial development, technological catch-up, and, politically, as a means for state survival (Amsden, 1992; Hobday, 1999; Wade, 1990; Yeung(Amsden 1992; Hobday 1999; Wade 1990; Yeung 2017). In this context, green industrial policy in East Asia and the wider Global South should be viewed as a new response to emerging challenges in the international economic system. These policies maintain several important continuities with past efforts at structural transformation. Therefore, national governments have promoted green industrial sectors and established new comparative advantages amidst overlapping global crises. These policies can be seen as a state response to the unequal nature of the global energy transition, the need to sustain participation in global supply chains, and to address structural financial disadvantages.

Despite the growing interconnections between critical minerals and clean energy technologies, East Asian states must navigate strategic competition between the United States and China, particularly in a context where China plays a pivotal role in regional manufacturing supply chains. Governments across the region are implementing targeted, government-led industrial policies to enhance technological sovereignty and important sectors like semiconductors and EVs, but they face challenges from uneven national capabilities and rising geopolitical tensions that impact global value chains.

The workshop aimed to address these issues by documenting the region’s experiences in an explicitly comparative manner. The organisers invited participants based on their country and sectoral expertise, which yielded a meaningful dialogue on the recent developments in East Asia—including China, South Korea, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and India—in shaping green industrial policies and navigating global supply chains. The discussions in the workshop will inform the development of an edited volume, entitled New Industrial Policy in the Asia Pacific: One Region, Many Pathways, which will be part of the forthcoming Bloomsbury-TNI Book Series Green and Fair Industrial Policy in the Global South: Transformative Pathways for Reclaiming Development.

Key Thematic Discussions

The workshop began with a keynote session by Professor Patarapong Intarakumnerd, which outlined the continuities and changes in East Asian industrial policies, specifically the shift from horizontal industrial strategies during the neoliberal era towards targeted, sector-specific strategies. Instead of relying mainly on broad support, such as R&D incentives, national governments across Asia have refocused their trade, investment, and finance policies in key priority areas, including semiconductors, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence (AI). For example, Japan has established regional partnerships, while Taiwan has strengthened its chip security and national supply chain.

Intarakumnerd highlighted the return of extensive government support as a means to advance further in emerging supply chains in the region and beyond. China and Taiwan have worked closely with private companies, offering subsidies and attracting global firms, such as China’s push to localise iPhone production. These policies must be understood as guided by new objectives, notably technological sovereignty and control over new supply chains, thus enabling further control over critical technologies in the high-tech sectors. In Southeast Asia, there are mixed results in the success of new industrial policies. Vietnam has developed local champions (e.g., VINFAST), whereas most countries, such as Thailand in the automotive sector and Malaysia in electronics, rely on foreign-led global value chains. Finally, the keynote highlighted geopolitical tensions as the primary disruptive force in global manufacturing supply chains.

Daniel Chavez discussed the complex realities of green industrial policy for the Global South, emphasising that the push for a green transition comes amid overlapping global crises—climate change, energy instability, economic uncertainty, growing inequality and the rise of far-right and authoritarian politics. He noted that while the transition is urgent, it is also costly, and countries in the Global South face significantly higher borrowing costs than wealthier nations, making it more challenging to invest in green development. Chavez also raised concerns about ownership and control, noting that most green technology patents are held by high-income countries and China, which limits technological sovereignty in the South. Even the promise of green jobs does not always mean decent or secure work, and many Southern countries risk remaining consumers rather than producers in the greening economy. However, he emphasised a growing trend—the return of the state—as countries like Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Indonesia revive state-led industrial strategies to reduce reliance on multinational corporations and support national goals. Chavez concluded that for green industrial policy to be effective in the Global South, it must address deep-seated structural inequalities in finance, technology, and global influence, and be shaped by local needs and strengthened regional cooperation.

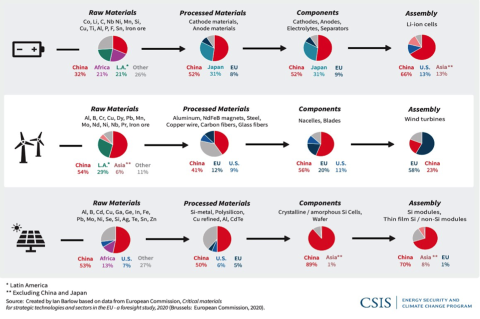

Jewellord T. Nem Singh explored the challenges and opportunities of green industrial policy in Asia, particularly through the lens of the energy transition. He highlighted that shifting to clean energy systems requires a significant increase in the extraction of critical minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, rare earths, and copper. The supply chain is also highly uneven, with mineral producers occupying the upstream segment. At the same time, higher-value-added activities in midstream and downstream are mostly dominated by Western and East Asian firms (see Figure 1). The growing demand for critical minerals raises important questions about environmental sustainability, resource dependency borne by mineral states in the developing world, and the inequitable distribution of costs in globalised supply chains. While these minerals present an opportunity for structural transformation in Southeast Asia, few countries are fully engaging with this opportunity—most still focus more on manufacturing as the primary driver of foreign direct investment and industrial strategy. Nem Singh likewise emphasised China’s central role in shaping Southeast Asia’s industrial and supply chain integration. Specifically, regional prospects for new industrial development are increasingly tied to China’s economic trajectory. He outlined three main types of industrial policy at play: functional policies, capital mobilisation, and technology promotion. In this context, the workshop aimed to explore the diversity of new industrial policies amid global strategic competition, examine shifts and continuities in policymaking, and draw lessons on the conditions necessary for successful industrial development in other regions.

Source: Nakano, J (2021) The Geopolitics of Critical Raw Minerals Supply Chains. Washington DC: CSIS, p.

Faizal Yahya presented Singapore’s Green Plan 2030 as a comprehensive strategy to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, with a target of sourcing 60% of electricity from low-carbon sources by 2035 through solar energy, regional power imports, and emerging technologies. He outlined Singapore’s green industrial policy framework, built on four pillars: governance, regulation, direct investment, and economic incentives. The country is actively transforming its manufacturing sector from labour-intensive production to advanced, high-value industries, such as semiconductors, aerospace, and healthcare, with a strong focus on Industry 4.0, sustainability, R&D, and workforce reskilling. However, Yahya noted key challenges, including rising operational costs, skills shortages, global supply chain dependencies, and the absence of standardised sustainability metrics. In response, the government’s Manufacturing 2030 plan aims to boost sectoral value by 50% while maintaining its GDP share. Strategies include innovation investment, digitalisation, talent development, and the use of tools like the Smart Industry Readiness Index (SIRI) to track progress. A strong emphasis is placed on tripartite collaboration among government, industry, and academia. Budgetary support is also critical—Singapore’s 2024 and 2025 budgets provide funding to drive innovation, support the energy transition, reduce business costs, and prepare the workforce for a competitive and sustainable future.

Yingfeng Ji provided insights on China’s distinct model of resource governance, which is characterised by its dominance in the midstream and downstream stages of the global rare earth supply chain—particularly in refining and fabrication, where it holds over 50% of the market share. This dominance is underpinned by an integrated value chain strategy, with the government actively supporting every stage—from upstream mining to downstream applications, such as electric vehicles and hydrogen technologies—through coordinated subsidies, regulations, and industrial planning. Ji highlighted China’s “push-and-pull” linkage strategy, where state-driven upstream development is guided by strong demand from advanced downstream industries, reversing the traditional path of resource-led industrialisation. Resource governance in China also serves as a tool of economic statecraft; export controls and environmental standards are used not only for industrial upgrading but also to strengthen geopolitical leverage and supply chain resilience. However, recycling and sustainability are ongoing challenges. While progress is being made in refinery-level recycling, end-of-life product recycling remains fragmented and policy-dependent, raising concerns about long-term environmental impact and waste management.

Zixuan Han added further insight into China’s industrial policy by highlighting its dual approach—combining strong state control with market-shaping tools to support mission-critical sectors such as rare earths and semiconductors. China employs both coercive instruments, such as quotas and export bans, and facilitative tools, including subsidies and public procurement, depending on the strategic needs of each sector. Han emphasised that the choice of policy tools is context-specific, influenced by factors such as the sector’s position in the value chain, the presence of externalities, and the ease of substituting technologies or inputs. This modular and adaptive policy framework could offer valuable lessons for late-industrialising countries by demonstrating how a flexible mix of interventions can be effective even in weaker institutional environments. Importantly, Han also provided rare sectoral data, particularly on rare earths and semiconductors, offering new empirical evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of China’s industrial strategy.

Vũ-Thành Tự-Anh presented Vietnam’s green industrial strategy as a bold move from aspiration to structural transformation, grounded in strong national commitment and clear objectives. The country has set ambitious targets—net-zero emissions by 2050 and a shift to 75% renewable energy—supported by key policy frameworks, including the Green Growth Strategy, Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8), and the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). At the core of Vietnam’s green vision are five pillars: economic restructuring, decarbonization, circular economy, climate resilience, and inclusive development. However, Tự-Anh emphasised two major dilemmas: balancing the speed of transition with limited institutional and financial capacity, and managing green reforms while sustaining high economic growth. Strategic sequencing, prioritisation, and blended finance models are essential. He also identified significant policy and institutional challenges, including weak coordination across ministries, restricted access to green finance—especially for SMEs—and inconsistent local enforcement. Moving forward, Vietnam’s success will depend on integrating green goals into priority sectors (such as textiles and electronics), expanding green finance tools, developing green skills and human capital, fostering innovation, and scaling eco-industrial zones. Ensuring a just and inclusive transition for workers and regions remains a critical part of this transformation.

Jong-Cheol Kim and Hanna Cho addressed South Korea’s evolving industrial policy through the lens of its semiconductor sector, which the country views as both an economic engine and a strategic asset in the context of intensifying U.S.-China tech rivalry. South Korea has prioritised public-private investment partnerships, but unlike its global competitors, it leans more on tax incentives and infrastructure support than direct subsidies—limiting the speed and scale of its interventions. Kim and Cho identified key structural challenges, including political delays, a shortage of skilled talent, and overreliance on memory chips, which heighten Korea’s vulnerability in the global tech landscape. Despite these issues, active state intervention remains crucial to maintain economic momentum, particularly amid geopolitical uncertainty and climate pressures. They argued that industrial policy must go beyond economic goals to also ensure social equity and political legitimacy. Long-term success hinges on policy stability, which is increasingly threatened by domestic political polarisation. To safeguard strategic planning, stronger institutional insulation is required. Korea’s experience offers valuable lessons for other middle-income countries looking to overcome post-development hurdles and avoid falling into the middle-income trap.

Suppawit Kaewkhunok outlined India’s evolving approach to greening its industrial sector, tracing early leadership in linking poverty reduction and environmental concerns back to Indira Gandhi’s 1972 Stockholm speech. Over time, green objectives have shifted from being peripheral “co-benefits” to a central part of industrial strategy, especially under the Modi administration. Since 2020, India has launched major initiatives, including the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes and the Green Hydrogen Mission, to position itself as a global hub for green manufacturing. Kaewkhunok highlighted India’s strategic use of geopolitical shifts—such as the China Plus One strategy and partnerships like the Quad Clean Energy Supply Chains and IPEF—to attract green supply chain investments. The country’s developmental state model emphasises strong state-private collaboration, with large firms driving innovation and implementation. However, challenges remain, including balancing sustainability with growth, where green goals often take a backseat; overreliance on large conglomerates risks sidelining MSMEs and causing regional disparities; fragmented institutional coordination slows progress and limits access to clean technologies and affordable finance for smaller firms. Additionally, geopolitical tensions and domestic political uncertainties pose risks to policy continuity and strategic focus.

Roundtable on the Prospects and Challenges of Structural Transformation in Southeast Asia

After looking into each country’s insights on green industrial policy, one of the most interesting sessions was the roundtable discussion. The discussion was moderated by Jewellord T. Nem Singh and involved several speakers, namely Jenina Joy Chavez and Nepomuceno Malaluan from the Philippines, Vu Thanh Tu Anh from Vietnam, and Sirinya Lim from Thailand. The public event examined how the U.S.-China strategic rivalry—especially during the Trump-era trade war—has shaped green industrialisation in Southeast Asia.

The discussion about the Philippines began with references to the common perception that the country has been an exception in terms of successful structural transformation and industrial catch-up in Southeast Asia. Joy Chavez highlighted the shift away from industrial policy following the overthrow of the Ferdinand Marcos government in 1986. A major consequence of political democratisation was a shift towards neoliberal democracy, which led to intellectual and political gaps in fostering creative thinking for a coordinated green industrial strategy. Therefore, the alleged opportunity presented by the Trump tariff plan for the Philippines might be overly optimistic. The Philippines remains vulnerable due to its narrow export base, weak supply chain integration—particularly in manufacturing—and inadequate infrastructure.

Examining the experiences of Thailand and Vietnam, the panellists advocated for a targeted green industrial policy with strong support from civil society and reform coalitions. Thailand faces significant threats from U.S. tariffs impacting key export sectors and setbacks from halted Green Climate Fund contributions, yet it maintains ambitious green targets, including net zero by 2065 and an EV roadmap. Thailand’s strengths lie in developing sustainability standards, market diversification, and green innovation; however, it still needs to improve its supply chain management and implement more integrated government action. Vietnam benefited from an accelerated green transition due to increased FDI demanding ESG compliance, actively reforming policies and infrastructure; however, it grapples with export dependence, weak local supply chains, and low domestic value addition. The Vietnamese government is now focusing on strengthening domestic private firms, but risks rising big-business dominance and state capture.

At the regional level, ASEAN’s response remains fragmented, with limited cooperation on standards for emerging green sectors like EVs and batteries. Discussants emphasised that green industrial policies risk exacerbating inequality, as high-tech sectors tend to create fewer jobs, making social justice and just transition frameworks crucial. The panellists point to examples from other countries where large firms have successfully developed local SME supply chains through sustained policy support, training, and multi-sector collaboration, highlighting the need for long-term, inclusive strategies in Southeast Asia.

Reflections on the ‘Old and New’ Green Industrial Policy: Insights from the Workshop

Industrial policy has undergone a profound transformation over the years, with its characteristics evolving across six key dimensions: objectives of industrial policy, global context, domestic politics, unit of analysis and execution, policy instruments, and targeting strategies. These dimensions reflect the shifting priorities and approaches Asian nations have adopted to address both traditional and emerging economic, social, and environmental challenges.

The first dimension of change lies in the fundamental objectives driving industrial policy.

Old Industrial Policy Objectives: Historically, industrial policy has primarily focused on achieving economic growth, enhancing competitiveness, and promoting product and industrial diversification. A significant aim was also to develop technologies and innovations and integrate them into the Global Value Chain (GVC). These objectives were largely economic, aiming to achieve national prosperity and strengthen specific industries.

New Industrial Policy Objectives: The “new” industrial policy encompasses all the traditional objectives but expands significantly to address contemporary challenges and broader societal goals.

- Crucially, it now includes the pursuit of technological and resource sovereignty, reflecting a desire for national control over critical technologies and natural endowments.

- Furthermore, there is a strong emphasis on redistribution, ensuring that the benefits of industrial development are more equitably spread, specifically targeting Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and particular geographical areas for structural transformation.

- Promoting “good jobs” and enhancing social welfare are also explicit objectives, moving beyond capital accumulation as the baseline objective of economic growth. This may well be a reflection of the shortcomings of both old industrial and neoliberal policies to address social well-being.

- A defining feature of this new paradigm is the integration of “green” as a necessary condition, meaning ecological concerns are no longer secondary but are fundamentally part of industrial development.

The second critical distinction between old and new industrial policies is observed in their respective global contexts.

Old Industrial Policy Global Context: The era was characterised by the shift from post-war self-sufficiency towards the gradual embrace of economic globalisation, where more, not less, global market integration in supply chains was desirable. Regional supply chains were prominently linked, often exemplified by the “flying geese model” where industrialisation spread sequentially across Asian economies. There were clear incumbent countries and technologies, such as the dominance of the United States and Japan in advanced electronics. The global economic order was more predictable, with established leaders and clear pathways for technological catch-up and integration.

New Industrial Policy Global Context: The contemporary landscape is characterised by a higher level of deglobalisation, leading to what has been described as “fragmented globalisation”. This fragmentation causes the splitting of regional and global supply chains, especially regarding critical technologies. The metaphor of “flying geese” has shifted to “the Dragon and the eagle,” highlighting the intensified competition and rivalry between major global powers, notably China and the US, which are influencing global industrial strategies. Geopolitical tensions and the focus on national security and resilience greatly shape trade and investment choices, resulting in a less integrated and more segmented global economy.

The third dimension contrasts the nature of the developmental state and its interaction with society, shaped by domestic politics.

Old Industrial Policy Domestic Politics: This approach was typically underpinned by a developmental bureaucratic state. This implied the presence of strong and capable state agencies, staffed by highly skilled technocrats, who played a central role in guiding industrial development. The relationship between the state and businesses was characterised by “embedded autonomy,” where the state maintained a degree of independence from particularistic interests while still being deeply connected to and understanding the needs of key industries. This allowed for effective long-term planning and decisive implementation.

New Industrial Policy Domestic Politics: The new paradigm shifts towards a developmental network state. This signifies a more distributed and collaborative approach, recognizing that the “capability of the whole society” is crucial for effective industrial policy. The relationship evolves into a “state-extended Society” model, which explicitly includes Multinational Corporations (MNCs), universities, and civic organizations in the policymaking and implementation processes. This implies a more inclusive governance structure where diverse stakeholders, beyond just domestic businesses, contribute to and benefit from industrial strategies.

The fourth area of divergence pertains to the geographical and organisational scope of industrial policy implementation, which is determined by the unit of analysis and execution.

Old Industrial Policy Unit of Analysis and Execution: Traditionally, industrial policy was predominantly conceived and executed at the national level. Focus was often on the sectoral level, aiming to develop specific industries. The interaction and impact on different types of enterprises were primarily considered in terms of conglomerates, SMEs, and MNCs within a national context.

New Industrial Policy Unit of Analysis and Execution: The “new” industrial policy significantly broadens its scope, incorporating traditional units while expanding to multi-level governance. It now includes Regional Industrial Policy (e.g., ASEAN-wide initiatives), Sub-regional Industrial Policy (e.g., within Core ASEAN groupings), and even Sub-national Industrial Policy (e.g., individual states within countries like India). Furthermore, the analysis of enterprise types expands to include start-ups alongside conglomerates, SMEs, and MNCs, recognising their growing importance in innovation and economic dynamism. This multi-scalar approach allows for more tailored and localised interventions.

The fifth dimension highlights the evolution of the tools and mechanisms employed in industrial policy.

Old Industrial Policy Instruments: Traditional instruments included various financial incentives, such as low-interest-rate loans, conditional subsidies, tax credits, and reimbursements. Infrastructural support was crucial for industrial development. The formation of consortia among firms was also a common strategy to foster collaboration and scale. Additionally, trade-related measures like export restrictions and quotas were often utilised to protect domestic industries or manage trade balances.

New Industrial Policy Instruments: The “new” industrial policy retains many of these traditional instruments but introduces a range of new ones to address contemporary challenges. Notable additions include:

- The Just Transition Fund (JTF) is designed to support regions and workers transitioning away from fossil fuel-dependent industries.

- National Reskilling Platforms are being developed to equip the workforce with skills necessary for new, disrupted technologies.

- There’s an increased emphasis on direct support for innovation through Venture Capital for start-ups.

- Furthermore, Competition Law is now considered an integral part of policy instruments, used not just to prevent monopolies but to actively shape markets in line with industrial policy objectives.

The sixth and final dimension illustrates the shift in how industrial policies identify and focus their efforts.

Old Industrial Policy Targeting Strategies: Traditional industrial policy often employed industrial targeting (vertical), where specific sectors were identified for growth and support. Additionally, area targeting was common, focusing on developing specific geographical zones, such as the Hsinchu Science-Based Industrial Park in Taiwan or the Tsukuba Science City in Japan. Instrumental targeting (horizontal), which focused on providing general support mechanisms like R&D tax credits or export promotion across various industries, was also used.

New Industrial Policy Targeting Strategies: The “new” industrial policy adopts a more strategic and holistic approach, moving towards mission-oriented targeting. This means that policies are designed to achieve specific societal objectives, such as achieving climate neutrality or driving digital transformation, rather than simply promoting a particular industry. Furthermore, there is a strong focus on targeting critical technologies, especially general-purpose technologies (GPTs) that have wide-ranging applications and transformative potential across multiple sectors. This strategic targeting aims to address grand societal challenges and secure national technological leadership.

In conclusion, the workshop highlighted the profound evolution in industrial policy. While retaining core economic objectives, the new paradigm is distinguished by its expanded goals encompassing social welfare and ecological sustainability, its navigation of a more fragmented global landscape, its reliance on a networked and inclusive state, its multi-level execution, its diversified policy instruments, and its mission-driven, technology-focused targeting strategies. This shift reflects a global response to complex, interconnected challenges that demand a more comprehensive and adaptive approach to industrial development.

Building on this momentum, the workshop has laid the groundwork for a tangible output that will make a significant contribution to the field of green industrial policy. A forthcoming edited collection, tentatively titled New Industrial Policy in the Asia Pacific: One Region, Many Pathways, will feature ten substantive chapters that explore green industrial policy and global supply chains within the Asia Pacific region. The publication will not only benefit stakeholders within the region but also serve as a knowledge-based resource to support the green industrial transition in Latin America and South Africa.

Moving forward, the workshop will be harnessed to maintain and expand the network of experts and academics specialising in green industrial policy, with the aim of consolidating individual national strategies into cohesive regional approaches. Additionally, the ongoing collaboration will facilitate the development of a series of regional industrial policy workshops, ensuring ongoing dialogue, knowledge exchange, and practical solutions for sustainable development in the Global South.

References

Amsden, Alice. 1992. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195076036.001.0001.

Hobday, Mike. 1999. ‘Latecomer Catch-up Strategies in Electronics: Samsung of Korea and ACER of Taiwan’. In Korean Businesses: Internal and External Industrialization, edited by Chris Rowley and Johngseok Bae, 48–83. London and Portland: Frank Cass.

Juhász, Réka, Nathan Lane, and Dani Rodrik. 2024. ‘The New Economics of Industrial Policy’. Annual Review of Economics. Annual Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-081023-024638.

Nem Singh, Jewellord T. 2023. ‘The Advance of the State and the Renewal of Industrial Policy in the Age of Strategic Competition’. Third World Quarterly, June, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2023.2217766.

Wade, Robert Hunter. 1990. Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. https://books.google.nl/books?id=n_9ZDwAAQBAJ.

Yeung, Henry Wai-chung. 2017. ‘State-Led Development Reconsidered: The Political Economy of State Transformation in East Asia since the 1990s’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10 (1): 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsw031.