Reforming pattern of land use, web of land access and mosaic of property institutions Issues for reflection in the context of COP30 and ICARRD+20

Topics

Regions

Land, climate change, and inequality are deeply intertwined. As COP30 and ICARRD+20 approach, this reflection argues that democratizing land control—not market-based “green” solutions—is key to confronting capitalism’s roots in ecological destruction and building a just, regenerative future.

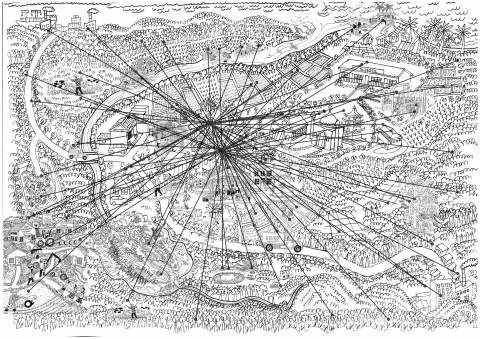

Credit: Federico ‘Boy’ Dominguez

Land, climate change and extreme inequality are inherently linked. A particular configuration of the inseparable land use pattern, web of land access, and mosaic of property institutions (that is, rules that govern land use and access) is the historical outcome of, and is organized to sustain, global capitalism which is, in turn, the cause of our environmental crisis and social inequities. Reforming land use, land access and property institutions – the land regime – can either reinforce capitalism, or erode capitalism while building an alternative positive future. Catch-all concepts like ‘land tenure security’ or ‘preserving tropical forests forever’ only make sense when seen in the context of what they do for or against capitalism. The three spheres of land use, access and property institutions – with emphasis on the pattern, web and mosaic – are intertwined: what happens to one partly determines the fate of the other. We cannot isolate a block of 50,000 hectares of officially recognized forest conservation project from the adjacent 100,000-hectare monoculture of soya, the latter from the adjacent fields of hydrocarbon extraction, and the former three from a nearby Indigenous people’s territory. In fact, this entanglement is global. For example, changes in land use, web of land access, and mosaic of property institutions in the Amazon are directly or indirectly linked to changes in land use, access and property institutions in the Netherlands through the importation of soya for the industrial livestock and dairy sector.

But isolating sectoral issues, such as forest conservation from monoculture, or Indigenous and peasant territories from agribusiness plantations, has been the defining character of mainstream land-based climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, as well as market-based land policies. It loves showcasing pockets of conservation projects here, and conceal the wider fields of destruction somewhere. These climate actions are meant to maintain the status quo, not to undermine it.

There are two important intergovernmental events by the end of 2025 and in the beginning of 2026: the United Nations Climate Change Conference, popularly called Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, happening in Belem, Brazil in November: COP30, and the FAO Committee for Food Security (CFS) mandated International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD+20) in Cartagena, Colombia (the last ICARRD was in Brazil in 2006).

Many of the climate change mitigation and adaptation projects (carbon offset projects, REDD+, etc.) and future plans – especially COP30’s centerpiece initiative, that is, the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) – are market-based. Meaning, exploring solutions to climate change within the same absurd idea of a limitless economic growth: pursuing endless profit-making through a logic that does not include in commodity pricing the social and ecological costs of commodities. False solutions to climate change through market-oriented land-based mitigation and adaptation projects have something to do with capturing land control, restructuring social relations around land, and repurposing land uses. It is contributing to the already alarming pace and extent of land concentration in the South and North which is the subject of ICARRD+20.

These two events therefore are bound by a common issue of interest. But the way they want to address their understanding of the question of land can be oppositional: corporate climate action is likely to further landlessness of ordinary working people, while a new way of understanding agrarian reform in the twenty-first century could lead to genuine democratization of land politics.

The ability of rural working people, peasants, pastoralists, fishers and Indigenous peoples to survive and flourish – their ability to continuously reproduce life, community and society –depends on having control of the means of production and social reproduction, that is, land. Conventionally, this is understood as having a plot of farmland, or a block of pasture. The reality is far more complex than a household having a plot of farmland. Rural working people need land for multiple purposes through layers of access to land and nature, and under different formal and informal institutional arrangements. If we draw this, we will come up with a web-like illustration or the mesh of access to land and nature, and a mosaic of different property relation arrangements. This concept of a web of access and mosaic of property relations includes a plot of farmland or block of pasture, but goes far beyond it. The character of the web and mosaic in turn shapes the integrity of an agroecological zone, a landscape, or a territory of human-nature relations.

Decades of neoliberal capitalism has made the highly unequal world even more so. Today, an estimated 1% of the world’s population has wealth equivalent to the combined wealth of the bottom 50%. This inequity is mirrored in the concentration of land ownership. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization reported that the top 10% of largest landholders operate on average 56% of agricultural land. Global land grabbing during the past 20-30 years has certainly contributed to this increasing land concentration.

The struggles within and against capitalism, ecological plunder, racism and patriarchy require a fundamental element – that is, the struggle to democratize land control. Conversely, struggles of rural working people could be exponentially stronger if these are able to go beyond being merely sectoral and merely agrarian – and connect to wider struggles that are intersectional in character. Here, class analysis and struggles are fundamental, but at the same time not enough. Class is a key reference point for grounded analysis and relevant political action. But because class relations interlock with other axes of social differences: gender, race and ethnicity, caste, generation, among others, class politics on its own is not sufficient.

Struggles by working people, peasants and the Indigenous also require allies inside and outside the state, inside and outside academia, and institutional conditions that are supportive of land struggles. This brings us to an important intergovernmental gathering that will happen in Cartagena in Colombia in February 2026, the International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development, or ICARRD+20. “Plus 20” because the last ICARRD was in 2006 in Brazil. ICARRD+20 is being hosted by the Colombian government, led by Minister Martha Carvajalino of the Ministry of Agriculture. It aims to chart a new path towards democratizing land politics for building a positive future of humanity, a new way of understanding that the current Colombian government frames as a revolution for land, life and society. The slogans of ICARRD+20 are: land to have food, land to work, land for peace, land for life.

Some 5,000 peasants, Afro-descendants and Indigenous from Colombia, hundreds of social movements such as La Via Campesina and IPC for Food Sovereignty and engaged scholars from around the world are expected to gather in Cartagena. An autonomous academic space at ICARRD+20 will be held at the University of Cartagena and is co-organized by the Red de Academicos y Investigadores hacia el Pacto por la Tierra y la Vida (a network of more than 200 engaged researchers from 38 universities in Colombia) among many other international research networks and institutions. It is a follow up on the October 2025 conference at PLAAS in the University of the Western Cape in South Africa and the ‘Cape Town Declaration’ that came out of that conference.

What do we talk about when we think about the politics of land in the context of COP30 and ICARRD+20? We offer some reflection points.

We put forward ten issues for reflection.

First, mainstream market-based climate change mitigation and adaptation projects often lead to land grabbing in the name of the environment, or green grabbing.

Second, corporate climate action entities are emerging to be a new landed class. Powerful entities (corporate, state, philanthropies) have elevated themselves in terms of taking control vast areas of land, and plan to seize more. Today, they are just as dominant in controlling vast lands as agribusiness and conventional landed classes. They have contributed to the increasing land concentration worldwide.

Third, conventional agrarian reform focuses on redistributing big private estates – latifundia – to landless people. This is key, but far from sufficient. Landed classes, agribusiness and other elites seize control of land through all types of property relations: private with alienable rights, private leased, state, public, customary tenure, and various hybrids. Official statistics about land are notoriously unreliable because powerful individuals and corporations control land through a combination of private, public, customary and hybrid property systems. It is likely that landed classes and agribusiness actually control more land than what official reports on private ownership show. Meanwhile, large databases estimate that land grabbing has implicated a quarter of a billion hectares of land worldwide. But databases on land investments generally miss the many small-scale non-corporate formal and informal ‘pinprick’ type of land grabs that are also part of wider land rush. Deep reforms have to democratize land control, and thus necessarily require targeting all types of property categories used by elites to control land.

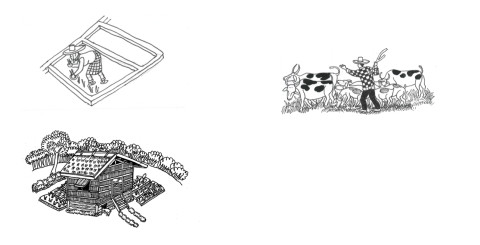

Fourth, for rural working people, what is fundamental is to gain or retain control of the web of access to land through diverse institutional mechanisms. The conventional agrarian reform concept is focused on the private plot of farmland for production. This is important. But no one can live just by having access to a plot of farmland (see Fig 1).

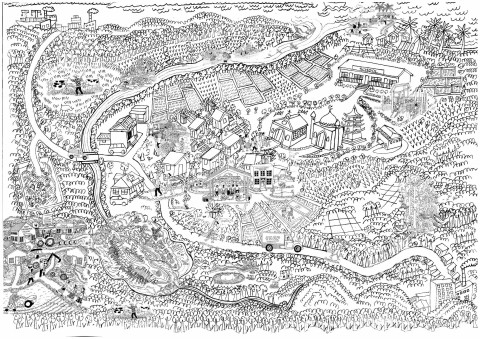

Working people also need access to land for housing, for chagra or kitchen garden, for community forest, landing space to access the sea, lake or river, land access for a right of way, playground for children, access to water, spiritual spaces, community space to reproduce culture and politics of society. Illustrated, it will look like a web (see Fig 2 and Fig 3). Most of these are non-commodified. These kinds of access to land are crucial for working people’s daily survival, or daily life more generally (or social reproduction). If we understand land in production and social reproduction, then access to land is necessarily plural, diverse and layered.

Institutional property systems are needed to support this web of access to land are better understood as a mosaic of private, public and commons and of hybrids. Each property system is distinct and important, but always embedded in a broader set of various types of property relations. Property relations when viewed beyond a plot of land, and from an agroecological zone, landscape, or territory will look more like a mosaic.

It is the web of access to land and the mosaic of property relations – not the plot of land or block of pasture – that are key to sustaining the integrity of an agro-ecological zone, or a landscape, or a territory, and that enable the continuous renewal of life and society.

It is thus the web of access and the mosaic of property relations that ought to be the unit of analysis and public action interventions toward democratizing land regimes. This is the true meaning of the popular phrase, “Land is life”.

Fifth, democratizing land regimes means land policies of redistribution, recognition, restitution and regulation as an inseparable set. Redistribution is needed to reduce the monopoly control of the few and transfer that land control to those who do not have it. Recognition is needed for those who still have access but are not formally recognized and protected - whether these are about land control by the Indigenous, women or youth. Restitution is for those who lost their web of access to land involuntarily. Regulation means affirming the need to put a ceiling to how much land one can accumulate, while guaranteeing a minimum access for those who need land to live. These 4 Rs are not a checklist where one can choose one or two, and discard the others. Far too long this has been what was and is happening, to divide and conquer the ranks of working people, peasants, Afro-descendants and Indigenous. Viewed from the 4Rs perspective, the already difficult challenge of reforming land politics has become even more difficult – because the aggregate land politics in an agroecological zone are far more complex, combining visible and less visible manifestations, fluid and dynamic that render the state-directed notion of planning which is in turn based on legibility and neat grid (such as official cadastre records) largely insufficient. Our argument has parallelism with Ian Scoones’ view (in his recent book on uncertainty) of state planning for development and ‘uncertainty’ seen from the perspective of pastoralists in which he argues in favour of not backing away from uncertainty but reframing our notion of planning instead.

Sixth, there is a need for a radical break from the past by seriously pursuing agroecological transition through regenerative land use and production systems. Even if we succeed in democratizing land politics, we may end up reproducing what happened in the past, that is, resorting to ecologically destructive uses of land: chemical agriculture, monoculture, pursuing the plantation ideal. We can end up reproducing the current capitalist industrial agro-food system marked by: agriculture without farmers, fishing without fishers, able to produce more than enough food to feed all people in the world and yet we have close to a billion people who are chronically hungry, converting farmland to industrial renewable energy projects and then justify clearing more forests to open up new plantations for monocrops. Or, as if often the case, promoters of false solutions to climate change celebrate the carbon saved by preserving a tropical forest in, say, 10,000 hectares of a project, while nearby, an agribusiness company just clear-cut a forest to open a new monoculture. Therefore, we need truly Regenerative ways of using land – an agroecological transition. Agroecological transition is only possible with prior or accompanying democratization of the web of access and mosaic of property relations that situates a plot of farmland or block of pasture within a broader agroecological zone.

Seventh, a genuinely nonreformist reform in the context of democratizing land regimes is the one that puts social movements at the heart of the political process. As Erik Olin Wright (2016) explained: “The appropriate orientation towards strategies of social transformation, therefore, is to do things now which put us in the best position to do more later by working to create those institutions and structures that increase, rather than decrease, the prospects of taking advantage of whatever historical opportunities emerge”. This is what it means by nonreformist reform. There is nothing inherent in agrarian reform to be a nonreformist reform or a reform that leads to a dead-end.

Aside from the importance of the institutional character of the reform, the role played by rural working people’s movements in interpreting and implementing reform is key in the making of a nonreformist reform. But historically, land policies were passed and implemented through technocratic and top-down approaches, overseen by corrupt officials and bureaucrats behaving like caciques. Therefore, a nonreformist reform of the politics of land requires a genuine Representation of all sections of rural working people and their social movements that are capable of representing the various social groups that are differently situated within the web of access to land and the mosaic of property relations in the agroecological zone. In a landscape where you have peasants, pastoralists, Indigenous and fishers, one sector, e.g. Indigenous, will be unable to represent all the rural working people. A broad alliance of agrarian social movements has to be the protagonist in the reform process that could keep ratcheting up reforms: reforms now, no turning back, to open for wider reforms in the future.

Eighth, democratizing land regimes means reforming pattern of land use, web of land access and mosaic of property institutions in favour of rural working people and the Indigenous, and it requires the inseparable principles of Redistribution, Recognition, Restitution, Regulation, Regeneration and Representation. This set of principles is for both pro-active and defensive struggles, including for resisting land grabbing. Reactionary land politics deploy these principles in ways that pit working people, peasants, and Indigenous against each other. There are several examples of this, two are illustrated here:

Redistribution without recognition. This happens where policies are meant to protect the property of landed classes, opting instead to encroach into and redistribute the lands of the Indigenous to landless peasants. Many internal colonization programs are like this.

Recognition without redistribution. Many of the neoclassical economics-inspired land policies aim to formalize existing land claims through formal land titling of customary lands – some provided freehold land titles with the right to alienate, others granted usufruct rights, with many hybrids. The bottom-line is: to recognize and formalize existing land claims without redistribution. But many customary land tenure areas are socially differentiated: rich peasants are economically and politically powerful with bigger lands, local chiefs and their clans control bigger lands, etc. In communities and societies marked by unequal land control, often in patriarchal systems too, formalization and regularization of land claims without redistribution means ratifying what exists and formalizing inequality.

Ninth, contemporary land struggles require new alliances, and a role for scholar-activists. Radical peasant politics is fundamental to land struggles. We need to take agrarian struggles seriously, but also try to go further – to link with environmental and climate justice and labour justice struggles. In this context, the role of scholar-activists is important, including in bridging different fronts of struggle, and as allies to social movements. Scholar-activism is a way of thinking and method of work that aims to interpret the world in rigorous scientific ways, in order to change it into something better: more just, fairer and kinder. It takes the side of the exploited and the oppressed unapologetically. Scholar-activists commit themselves to the social movements that aspire to change the world. This generates competing loyalties: to academia and to social movements, to academic rigour and to political rigour. This brings about a lot of contradictions in the conduct of scholar-activist work. Without social movements, gains in strategic struggles like democratizing land politics and food sovereignty are unthinkable. But with social movements alone, their struggles may be limited and constrained: they need allies – and scholar-activists are one of the key ones.

Finally, putting up an effective counter-narrative is urgent. Neoclassical economics thinking about land remains hegemonic, naturalizing dispossession and inequality, and preaching that land reallocation must only be through the free market, and so, has insisted on market-led land reforms worldwide that strengthened, not weakened, the landed classes and capitalists. Their narrative about the catch-all term ‘land tenure security’ is so influential, especially in the COP processes and IPCC reports – even when in reality it often only means ratifying what exists, which is: land politics marked by extreme inequality. Mainstream institutions control resources and infrastructure to sustain such a dominant narrative. It is not an easy task to challenge any hegemonic narrative, and denaturalizing land concentration and landlessness is a basic element in the struggle. Many of the historical struggles by the working class that delivered important victories, such as the 8-hour working paper, universal suffrage, women’s right to vote and civil rights movement, appeared daunting and impossible before their ultimate victories. We know that we are on the right side of history, and that is perhaps the most important starting point.

The idea of reforming the pattern of land use, web of land access, and mosaic of property institutions – or the land regime – through the inseparable principles of land redistribution, recognition, restitution and regulation, as well as agroecological regeneration and representation is not aimed at reproducing the logic of capitalism that is the source of ecological destruction and extreme social inequities. Rather, it aims to contribute to eroding capitalism while constructing an alternative system towards a positive future for humanity and the planet.

The ten points we proposed for reflection are not meant to be or to sound prescriptive. Rather, they are somewhat a comradely provocation, an invitation to a conversation about the need to broaden the agenda of what we talk about when we talk about democratizing land politics, whether in the context of COP30 or ICARRD+20.