Nasser’s dictum ‘No voice rises above the sound of battle’ has returned with brutal clarity in the era of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. This essay approaches the slogan not as nostalgia but as a contested political diagnosis: that in a region structured by settler-colonial violence and imperial proxy power, projects of democracy, development and social justice are repeatedly compelled to confront the unresolved question of liberation. Tracing debates on the Arab left from decolonisation to Camp David and the present, it argues that treating ‘rights’ and ‘reform’ as separable from Palestine misrecognises the primary contradiction—one that continues to organise repression, underdevelopment and defeat across the region.

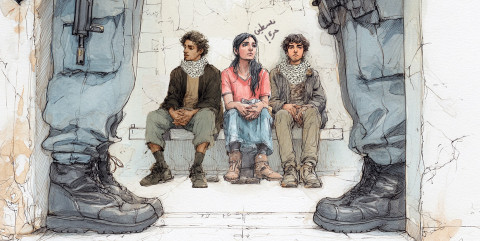

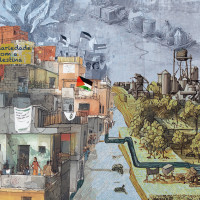

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Oh God...

Don't make me love good people again.

Oh God...

Don't make me adore my brothers' laughter again.

Oh God...

Make me hate my homeland.

‘May God Reward You, Uncle Abdel Nasser’, a poem by Abdelrahman Al-Abnoudi1

Whoever entangled us, has to save us.

‘Gana El Hawa’, a song by Abdel Halim Hafiz2

No voice rises above the sound of battle

Slogan coined by the late Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

No individual salvation

Any serious analysis of the modern Arab region has to view the formation of the militarised colonial outpost that is Israel as directly linked to how the region has developed in the 20th and 21st centuries. The early rejection of Israel by the Arab states was a recognition that the colony’s existence would impede projects of collective Arab political, social and economic development, prevent the emergence of strong Arab states, and help the US, Europe, and their allies to protect their access to the Suez Canal and routes to Iraq and India. Israel served to slow down, then eventually halt and reverse, the Arab modernisation project, with its aims of postcolonial sovereignty and development. Israel was a true “bulwark against Arab barbarism” as Theodor Herzl once argued. It also aimed to counter (if only secondarily), and act as an alternative to, the radical communist Jewish currents that existed in the region at the time, as Winston Churchill argued in a 1920 essay titled “Zionism versus Bolshevism: a struggle for the soul of the Jewish people”. It is in this context that Palestinian intellectual Mounir Shafik has stressed the Arab dimension of the Palestinian struggle:

Britain's experience with Muhammad Ali the Great in Egypt (1805–1840) led it to conclude that establishing an entity affiliated with the colonial project in Palestine was a crucial necessity to prevent Egypt from unifying the Arabs or from rising and transforming into a major and competitive state, as Muhammad Ali had achieved (making Egypt's army the fifth largest in the world at the time). The Zionist entity was planted in Palestine not because Palestine was the goal, but rather as a means of achieving the goal of seizing Egypt and preventing the unity of the Maghreb and Levant of the Arab world.10

Let us investigate this claim that, the issue of Palestine aside, the presence of Israel on Egypt’s border played a crucial role in its (de)-development. As one of the oldest countries in the region in terms of its modernisation project and its institution building, and with approximately 35 to 40 per cent of Arabs in terms of population, Egypt was historically primed to be a regional powerhouse. In the 1950s and 1960s under Nasser it made a serious bid for that role, with the blessing and support of the majority of the Arab population. After 1948, even prior to Nasser coming to power, the Arab press and public, especially in Syria (the other regional powerhouse), followed events in Egypt closely, including its fight with Great Britain. For example, in October 1951, commenting on the repeal of the treaty between Egypt and Great Britain, al-Ba’ath newspaper wrote that “the Arab people are rallying around Egypt”.11

However, a number of factors halted these ambitions. The expectations of the Egyptian and Arab peoples and states alike did not match the reality of Egypt’s capacity and capabilities, as a recently decolonised republic that was attempting to find its feet in a rapidly changing world while also attempting to delink its economy from the West. Egypt’s attempts to lead the pan-Arab project became a drain on its economy, especially as it was embroiled in several wars during this period (most notably in Yemen, where it fought against Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom), as well as providing support to other Arab liberation projects, such as Algeria. At the same time, it was attempting to achieve economic sovereignty and thus was unwilling to become dependent on the Western bloc. During this period Egypt benefited from the Soviet Union’s support of different liberation struggles in the Arab region and Africa, as well as its proximity to the Non-Aligned Movement. However, it never received the same level of support that first Britain and then the US provided to Israel.

Even in the period prior to the Bandung Conference (1955), when Egypt was still friendly with the US, the main point of contention between Nasser’s regime and the US was the latter’s position towards Israel. Then, after the Conference (at which the Non-Aligned Movement that launched Third Worldism was birthed), tensions were exacerbated when Nasser joined the Non-Aligned bloc and moved away from the Western camp. He had decided that this was the best route for Egypt to pursue, to chart its path regionally and globally. It was after this move that the US began to give its full-fledged support to the new colony of Israel. Yet Egypt was able to manoeuvre multipolarity dexterously to its own advantage, nationalising the Suez Canal in 1956 and then moving on to bigger ambitions, such as establishing the United Arab Republic (UAR) with Syria in 1958. The establishment of the UAR was a significant geostrategic change in the region. Syria, one of the strongest political entities in the region, which had previously hoped to establish Greater Syria and to unite the Levant, willingly relinquished its independent political existence to another regional political entity for the sake of Arab unity, with resounding support from both populations and across the Arab world. This was, and remains, an unparalleled event in international relations; it signalled to the world the seriousness of the pan-Arab ethos, and threatened to start a domino effect across the region. In fact, countries like Yemen and Iraq were both on the brink of joining the UAR, which would have been a blow to both imperial powers and the reactionary Arab regimes, represented by the Hashemite Republic of Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

The UAR lasted only three years, due to various internal factors. Nevertheless, the pursuit of independence and sovereignty continued. Due to its struggle against Israel, Egypt now found itself having to move closer to the Soviet camp as it sought to balance the support Israel was increasingly getting from the US. However, as stated earlier, Soviet support to Egypt never came close to the support Israel enjoyed from the US, especially after Israel proved itself capable of fighting the US’s Cold War battles, not only by defeating the Arab armies in 1967 but also by thereby scuppering the pan-Arab and socialist projects in the region, which, for many Arabs, became tainted with defeat. After its 1967 victory, Israel became an official imperialist outpost, watchdog, and proxy of the US. To this end, it received an unlimited supply of arms from the latter: while in the 1960s it received $834.8 million in US aid (30 per cent of which was military aid), in the 1970s it received a staggering $16.3 billion (70 per cent of which was military aid).12

The proxification of Israel was coupled with the empowerment of the reactionary forces in the region, represented by the oil-rich ruling regimes: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait and Qatar. From their founding, these regimes had been intertwined with imperialist and capitalist interests, and they formed the natural opposition to the Arab socialist and progressive projects. Nevertheless, they did participate in (and benefit from) what was to be the final demonstration of Arab unity: the oil embargo during the 1973 October War.

Just as the struggle with Israel led to Egypt’s Soviet turn, the same struggle – with its various forms of pressure – eventually led Egypt to move fully to the US camp in 1978, marking its official exit from the era of Nasser’s July Republic and its entry into a markedly different era – one we are arguably still living in. Egypt’s current political reality thus cannot be explained without understanding the effect of Israel on its journey as a modern republic in the second half of the 20th century, as summarised in the following paragraphs.

First, Israel’s violent founding and the Arab armies’ defeat in 1948, along with the loss of Palestine, ensured that the military became one of the main political actors in Egypt (if not the main political actor). Obtaining its legitimacy from the existential security threat on the country’s eastern border, Egypt’s military became a core component of the state. In turn, militarisation had consequences for political life and freedoms. As indicated earlier, the notion that “No voice rises above the sound of battle” meant that the national cause took precedence over social and political causes. This was continuously reinforced by the major wars fought with Israel over three decades – the 1956 Tripartite Aggression, the 1967 Naksa, the 1967–1970 War of Attrition, and the 1973 October War – which solidified the military’s legitimacy and served as justifications for the constant demands to strengthen it.

Second, Israel’s presence had an effect on the rise of Islamist political currents and the propagation of sectarianism and anti-left sentiments in Egypt and across the Arab world. Famously, after Egypt and Syria’s humiliating and course-altering defeat by Israel in 1967, the well-known Egyptian Sheikh Muhammad Metwalli Al-Sha’rawi controversially prostrated to God thanking him that Egypt did not defeat Israel as the victory would have been attributed to secular socialism at the expense of political Islam.13 The defeat was accompanied by Anwar Sadat’s move to weaken the left and Nasserites by empowering political Islamist tendencies, notably the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as by sending Egyptian labour to the Gulf, eventually resulting in the propagation of the extremist Wahhabi ideology in Egypt.14

Furthermore, Israel’s own rightward turn towards extremist religious tendencies also pushed Egyptians further towards Islamist currents that preach that dignity can only be restored through a return to tradition. This point has been made in several important contributions. In The Prophet and Pharoah, Gilles Kepel argues that the failure of secular Arab nationalism against an increasingly religious and expansionist Israel strengthened the ideological appeal of Islamist groups that frame the struggle in religious terms. Similarly, Raymond William Baker, in Islam Without Fear: Egypt and the New Islamists, argues that the rise of Likud and the entrenchment of religious nationalist settler ideology in Israel has reinforced Islamists’ argument that secular states are unable to defend Arab dignity and that only a return to Islamic tradition can confront Israel’s growing religious militancy. Moreover, in The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global, Fawaz Gerges argues that the expansion of the Israeli religious right, particularly after 1977, shaped Islamist discourse in Egypt whereby Islamists portrayed Israel’s rightward shift as proof that the Arab–Israeli struggle had become existential and religious. Gerges argues that this narrative boosted recruitment to the Muslim Brotherhood and its more militant offshoots.

It is important to point out, in the context of this discussion of the shift towards religious and sectarian currents, that Israel’s presence also created the binary of Arab and Jew, even though Arab Jews had lived in the region for centuries (indeed, they played a huge role in the establishment of communist parties across different Arab countries in the early 20th century). In fact, the Israeli Mossad worked to further this sectarian divide and to encourage the emigration of the Arab Jewish population outside of the region through fearmongering, including terrorist attacks on synagogues (as recorded in research by Avi Shlaim). Regarding sectarianism more generally, the harrowing Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon in 1982 stands out as an example of Israel both inflaming and making use of the sectarianism that was artificially engineered in the region as a result of its division (for the benefit of British and French colonialism) under the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement.

A third effect of Israel’s presence on Egypt’s modern history relates to the dissonance that arises from the fact that Egypt – which has the largest army and the largest population in the Arab world – even when supported by other Arab nations, has not yet been able to achieve a decisive victory or solution to the Israel problem, despite the clear disparities in size, history, and culture. This has created a persistent sense of defeat and confusion within Egyptian society – a feeling that is further exacerbated by the longevity of the conflict and of Israeli aggression. This continuing material and physical defeat has had spillover effects on Arab political subjectivity, affecting all political currents and the ability of individuals in the region to view themselves as active agents of history. This is evident in the domestic sphere in Egypt. With the end of the struggle eternally delayed, the difficulty of visualising a decisive solution creates a constant need to explain why there has not yet been such a solution, and why Egypt does not seem to progress while Israel does. This has resulted in the ubiquity of conspiracy theories and paranoid explanations, including arguments about internal betrayal and fifth columns (using cultural or civilisational explanations), and even supernatural or historical conspiracies.

This same logic has, in turn, created a segment of the society that rationalises and internalises Western propaganda that Israel persists successfully because it practices and promotes the values of the West. Zionism in that sense becomes more than just a settler-colonial ideology: it is presented by the Western powers as a way of life.

The famous adage, ‘it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’, can be similarly applied to Israel’s existence: it has become impossible to imagine the Arab region without the presence of Israel, despite its relatively short history. The question then becomes how best to navigate these ‘facts on the ground’. In line with this approach, rather than attaining true sovereignty, countries in the region now compete over who can rank highest in the US’s favourability ratings. This was recently witnessed when supporters of the Egyptian state rejoiced at the fact that it (and not Qatar) was hosting the ceasefire talks and the so-called ‘Peace Conference’ relating to the genocide in Gaza, attended by Trump. With the absence of, or unwillingness to find, solutions, the ceiling of aspirations is how to navigate this era of US and Israeli dominance over the region.

Given the vast gap between Egypt’s potential, its history and its current reality – as well as the fact that postcolonial Egyptian nationalism was forged in opposition to Israel – it is not hyperbole to say that the absence of an effective solution to the Israel issue has created a crisis of confidence in Egypt that affects all spheres of life. As Marxist Egyptian writer Mohamed Naeem observes, “it is as if the existence of Israel on Egypt’s borders is proof of our unworthiness as a state and as a people.” He goes on to state: “the problem is Israel’s existence, not the destruction it has wrought on the region as a result of its existence.” The sobering realisation is that the fate of the Egyptian people, and of the region as a whole, is not only shared, but also tied to, the fate of Israel.

The Egyptian masses are fully aware of the dissonance between Egypt’s potential, culture and history, and its aggrandising state discourse, on the one hand, and its current reality and its failure to act decisively to solve the Israel dilemma, on the other hand. Since the ‘peace treaty’ with Israel, in the form of the 1978 Camp David Accords, and the subsequent normalisation with the Zionist colony at the state level, increased repression has therefore been needed to reinstate a distorted version of the state.

This distorted version was temporarily interrupted from 2011 to 2013 (with the Egyptian revolution) and had to be restored through subjecting the majority of the population to one of the worst repressive regimes in modern history, imposing daily acts of discipline, punishment and impoverishment to ensure that the conditions of defeat and helplessness continue.

The use of repression in Egypt is not new. In the aftermath of Camp David, Sadat embarked on a wide crackdown, arresting 1,600 intellectuals, politicians and activists using diverse mechanisms of state control, including restrictive laws on assembly and expression and enhancing surveillance networks. After Sadat was assassinated on 6 October 1981, during a parade to commemorate the Camp David Accords, power passed to the regime of Hosni Mubarak. This regime was widely seen as continuing what Sadat had started, including the unpopular paths of neoliberalising the economy and deepening normalisation with Israel, while simultaneously increasing the state’s capacity for repression through enacting a permanent state of emergency, bolstering the security apparatus and widening the net of those subject to arbitrary detention and torture in prison. These are the factors that led to the eruption of the 2011 uprising, which was in turn followed by the counterrevolution and the violent reinstatement of the state that Sadat had birthed, characterised by further violence, repression and impoverishment.15

Ali Al Kadri explains the process summarised in the preceding paragraphs as follows: “[B]y fostering a sense of inevitability and powerlessness, violence helps maintain capitalist dominance. Without violence, the masses would not be tethered to the logic of capital; their existence and self-reproduction depend on the counter-violence they enact in resistance.” To address the extreme unpopularity of the Israeli settler colony in the region, the Arab ruling classes (including those in Egypt) were transformed into policemen whose job was to discipline the population, which in turn allowed them to consolidate their own power and interests. This allowed them to act as policemen towards their own people and, in return, to consolidate their own power and interests. The tendencies of resistance and liberation directly harm the interests of these ruling classes: if the Israeli state were dismantled, it would result in a complete overhaul of the region, stripping them of their power and allowing other political structures to emerge.

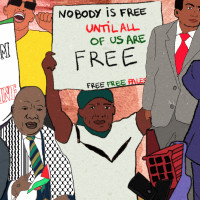

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

An unresolved defeat?

Much has been said about the epoch-shifting consequences of the 1967 military defeat, the Naksa (‘setback’). It was (and continues to be) the subject of analyses throughout the region and around the world; it featured prominently in cinema, literature and even music at the time; and its influence still lingers today, continually challenging the enduring dream of greatness and dignity that Nasser promised but which was never actualised. For many, the story ends there – with Nasser’s death marking the end of the unattained lofty ideals of pan-Arabism, socialism and Third Worldism. In this view, the defeat cancelled out any achievements Nasser might have made. “You let yourself down and you let us down... then you left, and took with you the nation's capabilities and hopes... until then.” Thus reads the last sentence of Sonallah Ibrahim’s 1970: The Last Days, a critical yet intimate elegy for the man who jailed him, but whose project he supported – albeit critically – until the end.

However, what gets left out of this narrative is what occurred in the decade between the defeat of 1967 and Sadat’s notorious visit to the Israeli Knesset 10 years later. There could not have been a worse scenario for the Egyptian military than what it experienced in 1967: its air force was almost entirely destroyed, and Sinai, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and the Golan Heights were occupied. Yet capitulation did not come until 1978. Israeli military commander and former minister of defence Moshe Dayan famously said that he was waiting for a phone call from Nasser and the Arabs in the immediate aftermath of the 1967 loss, conceding defeat and requesting a settlement. But that call never came. Rather, in the immediate aftermath of Nasser’s famous resignation speech after the defeat of 1967, thousands of people poured into the streets, rejecting his resignation and calling for him to remain in power. Some accounts portray the protestors as brainwashed, lacking options, or even planted. In fact, the protests were a conscious choice by an overwhelming majority of the Egyptian people who – knowing that Nasser’s chosen successor, Khaled Mohieddin, wished to ally with the US – were declaring their refusal to surrender.16 Through their protests, they were mandating Nasser to continue the struggle against Israel and declaring their willingness to continue to sacrifice for the cause of liberation.

Nasser complied, and shortly afterwards an Arab League Summit was called in August 1967 in Khartoum, where the famous ‘Three No’s’ were declared: ‘No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel.’

From that moment onwards, both the Egyptian state and society alike mobilised to contribute to the war effort against Israel. The titan of Egyptian and Arab music, Om Kolthoum, famously embarked on a national, regional – and finally an international – tour. The highlight was her legendary sold-out two-day concert at L'Olympia Theatre in Paris in November 1967, held to raise money for the war effort. She gave all of her fees to the Egyptian armed forces.17 Nasser’s famous slogan in his last speech before his death, “what was taken by force must be restored by force”, was internalised by Egyptian society as the defining slogan of the moment. It reaffirmed people’s commitment to armed struggle against Israel.

During this period, after a substantial restructuring, the Egyptian army began to rebuild its defence capabilities, with the help of the Soviet Union, and it mobilised along the Suez Canal, starting a three-year confrontation with Israel known as the War of Attrition. The goal of these military operations was not to immediately regain Arab territory but rather to rebuild the Egyptian army, restore its confidence in combat, and exhaust Israeli capabilities. It also sent a message to Israel that it would not be allowed to enjoy its 1967 spoils unchallenged. The newly formed Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) also participated in the War of Attrition, most notably in the 1968 battle of Karameh in Jordan between Israel and Palestinian guerilla fighters (fedayeen), in which Israel suffered heavy losses despite destroying the fedayeen base. A ceasefire between Egypt and Israel was declared in August 1970, with no clear winner. However, this hardly mattered because Egypt had achieved its military objective of breaking the Israeli streak of easy military victories, resulting in hundreds – if not thousands – of Israeli casualties, and causing the loss of between 24 and 30 Israeli aircraft. Of course, Egyptian losses were considerable – with tens of thousands of casualties, as well as the destruction of civilian infrastructure such as the Bahr Al-Baqar primary school and the Abu Zabal factory – yet the War of Attrition saw the Egyptian army and people regain confidence in their ability to confront Israel.18

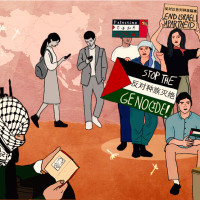

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Between two Octobers

It was this newly confident army that caught Israel off guard on 6 October 1973 by deftly crossing the Ber Lev Line. This line was considered impenetrable by the Israeli military but it was overrun in less than two hours by the Egyptian military, led by war hero Saad El Din El Shazly. Operation Badr began the October War and marked the first time an Arab army had decisively defeated the Israeli military in battle, shattering the myth of Israeli invincibility. However, after the initial breakthrough a disagreement over military strategy between Shazly and other senior military generals, on one side, and Sadat, on the other, allowed the Israeli military to regain ground a few days later. Shazly was compelled to comply with Sadat’s orders to extend the offensive despite his preference for consolidating the ground already gained. This led to what is referred to as ‘the gap’, space or breach in the Egyptian battle line between the Second and Third Armies in the Sinai sector during the later phase of the war, around mid-October 1973. This breach was exploited by Israeli forces, who crossed through it from the east bank of the Suez Canal to the west bank, enabling them to penetrate deep into Egyptian positions and eventually encircle the Third Army. Shazly and others later contended, countering the Egyptian state’s official narrative, that Egyptian armed forces could have gained more territory had Sadat not given that order, and many have questioned whether Sadat’s motivation was to secure moderate military gains which could be used as leverage in negotiations.19 In either case, some have argued that by prioritising diplomacy over military action, Sadat’s politics ‘failed the weapon’, meaning it undermined the success achieved by the Egyptian army and its assessments and directives. Others have argued that even if the Egyptian army had advanced further and won a larger victory it still would not have had the capacity to achieve a decisive victory that would have led to a permanent end to the conflict – though it would have achieved a more impressive military result than what ended up occurring due to Sadat’s unpopular intervention and overruling of his military chiefs.

Because Egyptian archives are not accessible to the public or scholars, it is almost impossible to obtain an official Egyptian account of the 1973 war. Historians must instead rely on memoirs, as well as Western and Israeli accounts, to try to piece together what happened. Shazly, largely considered a hero in Egypt and throughout the Arab world, was sentenced to three years in prison – serving one and a half – for disclosing war secrets during the era of Hosni Mubarak, who had previously served as a pilot in Shazly’s army in the October War. Nasserites credit Egypt’s military victory in 1973 to Nasser himself, arguing that it was his rebuilding of the army and of his generals, the experience gained in the War of Attrition, and his defiance of the Rogers Plan (in the form of moving the ‘missile wall’, Egypt’s integrated air-defence system, to the edge of the Suez Canal),20 that prepared the army for the confrontation. Others attribute the victory to the Egyptian people, highlighting their refusal to surrender after 1967 and their willingness to bear the burden of a constant state of war. It is certainly true that after 1967 the state had become more dependent on the Egyptian masses in relation to rebuilding the army and supporting the war effort.

It is worth underlining here that the consciousness, national identity and purpose of an entire class were forged in the military conflict with Israel. The people had paid the price of the 1967 defeat in at least three ways. First, they had experienced national defeat, in the form of a huge loss at the hands of a despised enemy, and they had no clear prospects for a counterattack. Second, they had borne the economic burden of war spending and the resulting supply shortages. Third, the classes that had expected to reap the benefit from Nasser’s universal free primary, secondary and tertiary education had instead found themselves engaged in indefinite military service. After 1967, therefore, the people were impatient in their demand for a decisive solution to the struggle. This was why, when he assumed the presidency in 1970, after Nasser’s death, Sadat faced immense pressure from the public to continue the war so as to regain the occupied territory. Some historians even claim that pressure from the student movement, which was particularly strong in 1972, played a significant role in the decision to launch the October 1973 attack. Certainly, student protests were sufficiently powerful that Sadat resorted to police force, thugs and tear gas to quell them.

Despite this support for war against Israel, prior to 1973 Sadat had sought to negotiate a settlement of the issue through the US. His entreaties fell on deaf ears: Israel was not interested in negotiating from what it considered to be a winning position.21 Hazem Kandil argues that it was due to this Israel refusal to negotiate that Sadat felt that he had to go to war. However, what is clear in the accounts of generals Saad El Din El Shazly and Mohamed Abdel Ghany El Gamasy is that Sadat did not aim to achieve a decisive military victory in 1973: rather, he wished to use the war to force Israel to the negotiating table. Henry Kissinger’s account of this period (which records his surprise at the way Sadat squandered Egypt’s gains), Sadat’s subsequent treatment of the 1973 military generation (stripping them of power and preventing them from recounting their narratives), as well as his decision to increase the power of the police in order to offset the military’s popularity after the war, showed that unlike the Egyptian people and the army he only wanted a calculated military incursion to achieve political goals, rather than viewing the war as the ultimate end goal. 1973 came to be known as the victory that was squandered through politicking.22 The Egyptian state, which claimed the 1973 war as its own victory, made 6 October a national holiday in Egypt, but then pivoted towards a different solution to the Israeli question: settlement. (It is worth mentioning here that the state’s narrative about the war removed the role played by ordinary Egyptians and the popular resistance in the canal cities in heroically stopping an Israeli advance towards Cairo.)

Between the Egyptian army's crossing of the Suez Canal and the destruction of the Bar Lev line in October 1973, on the one hand, and the 7 October 2023 Palestinian crossing of the Gaza iron wall and its destruction of the Israeli army’s Nahal Oz military base 50 years later, on the other, many events, reformulations and new equations reshaped the struggle against Israel. Yet the resistance in Gaza – despite Egypt’s normalisation – chose the anniversary of the crossing of the Suez Canal to launch its operation. This choice invoked the Palestinian resistance concept of tarakom (accumulation), according to which Israel can be defeated through a series of smaller defeats rather than a single decisive battle. The timing of the 7 October attack reminded the Israeli army of the first time the myth of its invincibility had been shattered, and the events of that day shattered it again. The parallel reaffirmed the Arab dimension of the Palestinian struggle, and also highlighted the similarities between the breakout from the biggest open air prison in the world (Gaza) into occupied Palestine and the Egyptians’ crossing of the Suez Canal.23

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

"I fear that on the day of victory we will regain Sinai but lose Egypt." - Ahmed Fouad Negm

يا خوفي من يوم نصر: ترجع سينا وتروح مصر - أحمد فؤاد نجم 1974

Ya Khofy min Youm Nasr: Terga’ Sinaa we Terooh Masr,

- Ahmed Fouad Negm.

The victory of 1973 would not have been possible without Arab solidarity. Egypt and Syria did not fight alone: all of the Arab states contributed to the war effort in one way or another, even if only through the provision of financial support.24 In particular, the implementation of the 1973 oil embargo against the West was a watershed moment. It was never repeated:25 subsequently, Henry Kissinger devised a new strategy for the region, whose core aim was to solve the ‘Middle East crisis’ by isolating each country and dealing with it individually, rather than dealing with the Arab countries collectively.26

When some opposition figures seek the origins of the extreme repression that Egyptians face today, they often trace them back to the July 1952 revolution that brought the Free Officers and Nasser to power, constructing a teleological narrative that links the Egyptian military of the 1950s and 1960s to today’s military. The state strengthens this narrative through its official historiography, utilising state-affiliated historians, school curricula and TV broadcasts. In contrast, counter-narratives argue that this account is overly simplistic, and argue instead that the July Republic ended with the signing of the 1978 Camp David Accords, ushering in the Camp David republic that persists today (having been briefly interrupted from 2011 to 2013). The latter argument has become increasingly widespread over the past two years, in response to Abdelfattah Al-Sisi’s choices during the genocide in Gaza, which have exposed both Egypt’s lack of sovereignty and the cost of aligning with the US and the Gulf monarchies. Just as this period has clarified the nature of the West and its so-called ‘international rules-based order’, it has also brought into sharper light the role of comprador Arab regimes. Moreover, it has highlighted the widening gap between rulers and ruled, and demonstrated the extent of repression these states are willing to inflict upon their own people in the service of imperialism, as well as their own interests. It is in this context that the chant ‘Down with Camp David’ is still often heard on the streets of Egypt during protests, and continues to appear in the social media biographies and descriptions of Egyptians of different political persuasions. This slogan goes beyond criticism of the ‘peace treaty’ itself: it also expresses opposition to the complete shift in politics that it represented and the new republic that it ushered in.

Over the past two years, analysts have identified several cases of Israel reportedly violating the terms of the treaty with Egypt, such as occupying the Philadelphi Corridor and taking control of the Rafah border crossing. However, whether Israel has entered the stipulated demilitarised zones (Areas A, B or C) in the buffer zone in Sinai does not really matter, as from the start the broader aims of the treaty outweighed the details of its provisions. The treaty really reflected the political will of the Egyptian state under Anwar Sadat to give up the use of armed force in the conflict with Israel and move towards a settlement instead. If the political will to go to war with Israel does not exist, then the granular specifics of the agreement are moot – it would not matter if Israel were to violate all of its provisions. This may explain why Sadat did not seriously contest the terms of the treaty, reportedly saying: “I will sign anything President Carter proposes without reading it”, according to the memoirs of Mohamed Ibrahim Kamal, Egypt’s foreign minister at the time, who resigned in protest over the Camp David Accords.27

As indicated above, Camp David was more than just a treaty: it was the centrepiece of a broader political project, marking the beginning of the Camp David republic. The Accords encompassed normalisation with the enemy and set the stage for Egypt’s neoliberal open door policy (infitah), which was a departure from Nasser’s planned economy. This project saw Egypt move away from nationalisation and towards privatisation, and from the ambitions of industrialisation and national production towards a service-based import-oriented economy. This period saw financial interventions through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, accompanied by the usual harsh conditionalities. In fact, the lesser known January uprising was the January ‘Bread Intifada’ of 1977, when thousands of Egyptians took to the streets protesting Sadat’s decision to remove bread subsidies as part of the conditionalities for IMF loans. Sadat deployed the army to quell the protestors, resulting in dozens of casualties and hundreds of injuries. Nevertheless, the cuts were reversed. It was in this context that, fearing that these events had undermined his legitimacy, Sadat sought to accelerate peace negotiations with Israel, partly in order to secure US support for his continued rule. This culminated in his infamous surprise visit to the Knesset in November of that same year, which shock both the Egyptian public and the Arab public more broadly.

Camp David’s most significant stipulation was that Egypt sever its ties with the Soviet Union and join the US camp – an outcome Henry Kissinger regarded as the most important accomplishment of the Accords. Egypt’s acceptance of this stipulation was the result of both global and regional shifts, notably the weakening of the Soviet Union and its lack of willingness or capacity to provide Egypt with support comparable to what Israel received from the US (with the exception of the missile defence system that Nasser secured from the Soviets under threat of resignation, which had helped rebuild the army during the War of Attrition and was vital in the October 1973 war). It was in this context that a significant segment of the Egyptian state and military were keen to move away from the Soviet camp.

In the global context, the Camp David Accords marked a significant shift in international relations: Egypt was one of the first countries – and was the first major country – to switch from the Soviet to the US camp within the space of just a few years. As such, it served as a test case for policies that were later applied to the Communist countries in Eastern Europe. While some argue that a similar shift had occurred in Indonesia in the late 1960s (accompanied by extreme violence), the shift in Egypt was perhaps even more significant.28 Egypt was at the centre of the Arab world, and at the forefront of the Arab–Israeli struggle, and so its move to the US camp changed the regional equation completely: it remodelled Egypt’s role regionally and globally, shrinking its influence and reducing its capabilities to the extent we are currently witnessing. As indicated above, Camp David was also Kissinger’s first attempt to conduct diplomatic dealings with an Arab state individually, rather than with all the Arab nations collectively. He chose to start with the Arab country that up to then had been the biggest threat – even an existential threat – to Israel. With Egypt neutralised and out of the equation, the groundwork was laid for the US to become the dominant external power. In this way, Camp David facilitated Israel’s regional dominance, severely diminished the Arab radical camp, strengthened the pro-US Gulf monarchies and in turn ensured that Arab oil wealth was closely aligned with US strategy. Camp David also led directly to the Oslo Accords, which created the Palestinian Authority, whose job is to act as a first line of defence for Israel against the resistance of the Palestinian people. Oslo in turn laid the groundwork for the Abraham Accords and associated Arab–Israeli normalisation that was advancing steadily until it was disrupted by the Palestinian resistance on 7 October 2023. Clearly, the Arab signatories to these successive ‘peace’ agreements have yet to receive a peace and prosperity dividend from them.

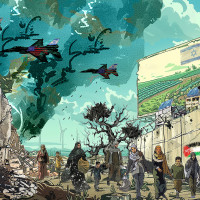

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Twilight of the Camp David era

Enough time has passed to say with certainty that the Camp David gamble has failed spectacularly for Egypt, while simultaneously being one of Israel’s most important strategic victories. The promised economic prosperity that Sadat had hoped for never materialised: Egypt did not become an Arab version of Japan. Sadat’s plan for Egypt to replace Israel as the US’s main ally in the region was also not realised. Indeed, there were no beneficial returns for this top-down enforced ‘peace’: the only real outcome was normalisation. Egypt, which until then was Israel’s biggest existential threat, and one of the most significant fronts in the conflict, was neutralised. Israel’s first action after the signing of the Accords and the ‘peace’ treaty was to invade Lebanon in 1982. This invasion signalled to the Arab world – and to Egypt in particular – that the treaty was to be upheld unilaterally and that, now that the Egyptian front was neutralised, Israel would continue to target Arab resistance wherever it might arise until it achieved the surrender of its enemies. The invasion quickly served to put to the test how closely Egypt would adhere to the terms of the treaty.

After the Camp David Accords, Egypt gradually lost its sovereignty, becoming economically dependent on the US and the Gulf monarchies. At the same time it had to increase its policing capacity in order to suppress not only political enemies of the state, but also the Egyptian working classes, who, in the new status quo, were left without dignity or social safety nets.

It is no surprise that the most commonly cited reasons for the January 2011 uprising included broad terms like ‘corruption’, ‘authoritarianism’, ‘personal freedoms’, and ‘democracy’. However, accounts which focus on these issues alone overlook the fact that the uprising was the result of accumulated grievances. Its momentum built over time: from workers’ strikes in Mahalla to protests supporting the Palestinian intifadas and opposing Egypt’s ongoing normalisation with Israel, to protests against police brutality targeting the working class. These elements came together in the collective rejection of the Camp David republic and everything it represented. It was in this context that, during the events of 2011, Egyptians repeatedly targeted the Israeli Embassy – storming the building and scaling its walls to tear down the Israeli flag. At least three Egyptian protestors died in these Embassy protests.29

Those who crossed and those who plundered

After the 2011 revolution, the counterrevolution, led by the current Egyptian regime, with the support of the Gulf monarchies, succeeded through unprecedented repression in forcefully restoring the Camp David republic – albeit with new characteristics. This process further entrenched Egypt’s relationship with Israel and increased normalisation. In 2013, a coup d’etat, which was supported by millions of Egyptians, enabled the Egyptian army to depose the Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi (who himself had not deviated from the Camp David republic). This process was marked by a series of state-sponsored massacres and violent crackdowns, including a massacre during the dispersion of Muslim Brotherhood supporters from the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque. In this deadly event it seemed that the violence that the state had earlier wielded against different segments of the population – including the violent dispersion of the Maspero Coptic sit-in in October 2011, and the Port Said massacre targeting Al-Ahly football ultras in February 2012, as well as various showdowns between the police and protestors in Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cario – came together to show the lengths the security forces would go to to end dissent once and for all. Together, these violent events transformed the role of the Egyptian army, reshaping both its self-perception and ideas about its legitimacy. Whereas the army had formerly justified its size and power by invoking the existential threat posed by Israel on the country’s border and the potential for renewed armed conflict, it now turned inward, justifying its role in crushing the revolution and killing Egyptians by references to ‘protecting the republic, and ensuring its stability’, and portraying Egypt as a sanctified fortress that must be protected in the midst of regional turmoil and civil wars – most importantly, protected from internal threats. In this narrative, the main enemy of the new republic has become the Egyptian people themselves, and the main threat is any form of collective organisation, political or otherwise. The state’s primary mission, supported by the Egyptian army, is to dismantle such organisation, whatever form it takes.

While the new regime has forced Egyptians to give up the hopes of 2011, it lives in perpetual fear of a recurrence of the revolution – another uprising or ‘revolution of the hungry’. Isolated from its people, the regime occupies desert fortresses much like the historic Mamluks did, interacting with society only through repression and dispossession.30

The Al Aqsa Flood operation and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people have brought the Egyptian state’s new role into sharper focus. Through both its actions and its inaction, the regime has demonstrated that it lacks the political will to take any action (like supporting Palestine) that would jeopardise its relationship with the US, and that it lacks the sovereignty to even attempt to do so. Instead, it appears to welcome its diminished role in the region, from the leader of the Arab world and the centre of Third Worldism to a state ruled by a US comprador regime which ensures Israel’s safety, acts as Europe’s policeman in the region (preventing illegal migration to Europe), and is unable to solve diplomatic questions in Africa (such as the issue of the Grand Renaissance Dam standoff with Ethiopia). Rather than recognising the national security threat that Israel’s current military campaign – marked by genocide and regional war – poses to Egypt and the region as a whole, the Egyptian state prioritises internal threats, particularly those that threaten its legitimacy the most. During the past two years, this has led to a nationwide crackdown in which even the most basic acts of solidarity with Palestine, like demonstrations, have been criminalised. Women – and even children – have been imprisoned for offences such as displaying banners, forming student groups for Palestine, breaking away from state-sanctioned protests, raising funds for a Palestinian food bank, or using social media to call for protests. Approximately 200 people involved in these actions remain in prison. Most recently, the regime has launched a petty diplomatic campaign against European countries that have permitted Gaza-related protests outside Egyptian Embassy buildings.

One aspect of the Egyptian state’s collusion with the Israeli genocide which has rightly caused outrage internationally is its use of the contractor Al-Argani Group to collect exorbitant fees both for goods imported into Gaza as well as from Palestinians in Gaza trying to escape Israel’s war crimes. This situation raises questions about why this organisation, which operates militias that reportedly control north Sinai, exercises authority over the Egyptian side of the Rafah border. Concerns have been raised regarding Sinai’s sovereignty, the reliance on armed militias to control it, and recent forced evictions and home demolitions in north Sinai, which have displaced residents and turned the area into an uninhabited buffer zone. Aside from the touristic cities in its southern part (where Egyptians are still subjected to numerous checkpoints), the north of Sinai remains largely inaccessible to Egyptians and it receives almost no national press or media coverage.

All of these measures – along with the Egyptian regime’s outright refusal to allow Egyptian, Arab or foreign delegations to exert pressure on Israel from within Egypt, in the form of the June 2025 March to Gaza campaign, which was refused permission to march in Sinai – underscore not just the regime’s thuggishness, but also its short-sightedness. For it is questionable whether a nation with such a large population can be governed in this way for much longer. Whereas the Camp David republic under Sadat invoked right-wing nationalism, embodied in the slogan ‘Egypt First’, to assert that Egyptian interests were not the same as the interests of the Arab world as a whole, the current regime does not even attempt to do this. Instead, it has aligned itself with a small elite who live in gated communities and are distanced from the vast majority of Egyptians. Ordinary people, meanwhile, are left with few choices: they can live as second-class citizens in their own country and provide cheap labour to boost profits for foreign capital (primarily Gulf capital), with no political or social rights, no access to public spaces, no unions, and not even the ability to form football fan groups – or they can risk their lives to migrate illegally, often risking death by drowning off the coast of Libya.

In this current unjust reality, a fundamental contradiction remains unsolved: although Egypt was the first Arab country to normalise relations with Israel, support for normalisation never trickled down to the general population. This is why the army – half a million strong and historically defined by its enmity towards Israel, having fought four major wars against it, with patriotic sacrifices on the part of generations of Egyptians– is now directed inwards, against its own people. This new raison d’être of the Egyptian military further serves Israel’s interests: if the army believes that any threat to its legitimacy will come from inside, rather than from across the eastern border (as generations of Egyptians have been taught), it will not be prepared for any future confrontation with Israel when it inevitably arises.

This dissonance between continued popular animosity towards Israel and state policy towards it leads to instances such as the one in June 2023, when a low-ranking 22-year-old Egyptian border security official stationed on the Egyptian–Israeli border shot and killed three Israeli soldiers, wounded two more, and was ultimately killed himself. The Egyptian authorities denied the young security official a military funeral, which would normally be held in such a case. Well aware that a public funeral would draw thousands to honour the martyr, they insisted that his family hold a private funeral instead. A similar incident occurred on 8 October 2023, when an Egyptian policeman shot and killed two Israeli tourists in Alexandria. These are not isolated incidents: famously, in 1986, the Egyptian soldier Suleiman Khater shot and killed seven Israeli tourists in Sinai. An Israeli businessman was also shot in Alexandria in May 2024: a group called Vanguards of Liberation later released a video claiming responsibility for the assassination and dedicating it to the children of Gaza. Such incidents are bound to recur in the absence of true peace between Egypt and Israel, which remains unattainable for historical, logical, objective and existential reasons.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Between the stick and the bullet

The Israeli genocide has given rise to new world in which naked aggression, annexation of sovereign territory and massacres of civilian populations have reached unprecedented heights and there is no longer any pretence that public opinion (which is strongly opposed to Israel’s crimes) matters. The ideals of democracy and personal freedoms – once regarded as the gold standard by many in the Arab region – have proven to be a façade. As militarisation intensifies, surveillance technologies advance, and methods of repression become ever more extreme and absurd, the masses are left facing a stark reality: their only option is to endure coercion and violence. They are offered no ‘carrots’, only a stick (sometimes in the form of bullets). Egypt serves as a stark example of imperialism’s vision for the region: capitulation is no longer sufficient – both the US and its rabid proxy now demand absolute submission, insisting that the people of the region endure constant and self-perpetuating states of defeat.

The explicit and unapologetic nature of the genocide in Gaza – and the unabashed support it has received from two US administrations, with the collusion of the UK and the European Union – signals the dawn of a new era. In this new era, women, men and children are killed in the most brutal ways, the laws of war are disregarded, and terrorists who masquerade as soldiers openly boast of their war crimes. Terroristic tactics, such as the pager attack in Lebanon in September 2024, are lauded for their precision, while the targeting of military and political leaders in other sovereign states is justified. Meanwhile, the genocidal state of Israel – midway through committing a genocide – is pursuing a wider regional war, escalating its settler violence in the West Bank, repeatedly striking Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Iran, and stationing its troops in Lebanon and Syria. This state functions as a bastion of death and destruction in the region as it seeks to achieve full regional submission, with military support from – and under the diplomatic cover of – the US.

As the Lebanese resistance faces growing pressure to surrender its arms, it is crucial to recognise that, throughout the region’s history, surrender and normalisation have consistently resulted in diminished deterrence and reduced leverage to resist Israeli aggression. In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that the foundations for the unrestrained atrocities we are witnessing today were laid in 1978, when the biggest Arab country, with the biggest military and population, withdrew from the struggle. Just as Palestinian factions drew a direct line from 1973 to 2023 through their choice of 7 October as the day of the Al Aqsa Flood operation, so there is a clear connection between the signing of the Camp David Accords and Israel’s ability to commit a genocide in Gaza unimpeded.

This makes clear why, upon his return to Lebanon after serving a 40-year prison sentence in France, the revolutionary Georges Abdallah highlighted Egypt’s central role in the region, stating:

The condition for freedom is calling on the Arab masses to take to the streets,

The condition for freedom is for the Egyptian masses to take to the streets,

The Egyptian masses,

The Egyptian masses.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Arab liberation from Arab occupation

Over the years, the Palestinian cause has been steadily narrowed and diminished to the point where even Israeli aggression in the West Bank is framed as a separate issue from the so-called ‘Israel–Gaza’ war, and where Israel’s war on Lebanon is treated as an isolated conflict and the occupation of Syria is also discussed independently of the surrounding context. The historical Arab dimension of the struggle has been completely stripped away from the Palestinian cause.

Gaza deserved – and still deserves – the long-awaited, almost mythical, ‘Arab awakening’. Even the darkest of imaginations would struggle to conjure horrors greater than those Gaza has endured in the last two years. Yet rather than rising to meet the moment and confronting – or at least lessening – these atrocities, the Arab states have failed to act. This inaction can be explained by the fact that the first brick of this crime was laid decades ago: the region has been engineered over a period of decades precisely to ensure that a catastrophe of this magnitude does not receive the collective outrage needed to end it – or even to mitigate its severity. It is this history that explains why Gaza has been left to face the harshest, most brutal edge of imperialism almost entirely alone. In the course of this history there has been no single pivotal moment (though the Camp David Accords in 1978 come closest), rather the shift has taken place gradually through decades of normalisation, during which the Arab world has decided to remove itself from the equation and transfer responsibility for the Palestinian cause solely to the Palestinian people. It has framed this shift as empowering the rightful owners of the cause to take the lead, while internalising narratives suggesting that individual solutions could exist for what is, in reality, a shared problem.

With each of the Arab countries caught up in the specificities of their local contexts, Palestine is now left to carry the immense burden of confronting an entity strategically placed in the region to perpetuate imperialist designs of subjugation, underdevelopment and suppression of the masses. In this context, Palestinians are often put on a pedestal and portrayed as superhuman, as ‘a nation of giants’ and an ‘invincible’ and ‘unyielding’ people – thereby giving the people of the Arab countries licence to relinquish their historical responsibility for sharing the burden, to the detriment of all. By consigning Palestinians to martyrdom as an inevitable fate, we avoid acknowledging that sacrifice is required from all of us. Moreover, in handing over control of what is, historically, materially and existentially, a collective struggle, the Arab countries have placed the enormous task of freeing the region and the world from one of its most barbaric actors solely on the shoulders of the Palestinians, who have borne the heaviest losses (alongside the Lebanese and Yemeni resistance).

This mindset – characterised by passive witnessing and nihilism – reflects the internal condition in the Arab countries. It reveals how Arabs see themselves in their own struggles: disempowered, disorganised, and disconnected from the levers of power. Elevating the image of the mythical Palestinian renders Arabs as bystanders, rather than active actors in history – a role that has been abdicated and handed to others.

In reality, a specific version of Arabism already exists: the counterrevolutionary, reactionary kind, which seeks to usher in a ‘post-masses’ era that aligns with the global ruling class’s indifference to public opinion. The reactionary Arab regimes who propagate this version of Arabism have always been the primary adversaries of the pan-Arab socialist project: they consolidated their power and allied with imperialism in order to defeat it. Secondly, just as the so-called Arab Spring was a distinctively Arab phenomenon, so too was the counterrevolution that followed. Finally, security coordination among Arab comprador regimes now operates on a systematic level: for example, if a Palestinian is deported or banned from Jordan, they won’t be able to enter Egypt; meanwhile, an Egyptian dissident might be apprehended in Syria, then extradited to and imprisoned in the UAE. Protected by this security coordination, and supported by a unified reactionary Arab media, Arab capital flows are extracted and accumulated through the dispossession of the Arab masses.

Yet just as reactionary Arabism exists, so too does the disadvantaged class of Arab masses across the region who share the same fate across different countries, and whose interests are fundamentally at odds with those of the ruling classes in their countries. Acknowledging this shared fate calls for careful analysis (rather than satire or blanket judgement/condemnation of an entire people) when popular frustration and political awareness in the region do not translate into mass action or visible street mobilisation. Historically, in moments of major mobilisation or direct confrontation with the state when the masses were able to impose their will or even topple governments – as in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011, in Jordan’s 1956 uprising against the Baghdad Pact, in earlier episodes during the colonial era and the era of Arab national liberation, and in the 1979 Iranian Revolution – the driving force was always a local, immediate and directly experienced crisis. In those moments, regimes were weakened, divided or in disarray, creating openings that ordinary people could exploit. It is demoralising to refer to current inaction as the result of character and aptitude rather than as the result of specific historical processes.

This dynamic differs sharply from Western contexts, where protest (even when met with some repression) takes place under fundamentally different political conditions. In those contexts, protest is often celebrated. At the same time, over the past two years Arabs have sometimes been subtly – or even explicitly – chastised for not protesting like their counterparts in Western countries, even though they face incomparably harsher forms of state violence and repression. Needless to say, such chastisement ignores the history of Arab uprisings.

This raises a deeper question: why are most Arab states governed through extreme levels of repression, and why are leaders allied with the West not condemned as dictators but instead supplied with the most advanced weapons, surveillance technologies, and training, enabling them to enforce that repression? Is it truly because Arab populations are submissive or cowardly? If Arabs were inherently passive or helpless, such vast systems of coercion, disciplinary institutions, and security apparatuses would not be necessary to keep them in a state of political paralysis. The scale of repression is itself evidence of the opposite: that a genuine popular uprising, one that expresses the democratic will of the people in this region, would pose a direct threat to US imperial interests. The realisation of that democratic will would trigger a profound crisis in the global political and economic order.

“A lot has passed, our homeland. Only a little is left.”

فات الكتير يا بلدنايابلدنا مابقاش إالا القليل - من اغاني فرقة أولاداولاد الأرضالارض

(A popular resistance song from Suez.)

As the Palestinian cause has been steadily narrowed, ‘Arab’ and ‘Palestinian’ have increasingly come to be defined along identitarian, racial or ethnic lines, rather than being political categories. Yet it remains evident that the history of the Arab world during the era of so-called modernisation is also the history of the Palestinian cause. Historical resistance to Zionism has been fundamentally Arab in character – including in its Islamist dimensions. It is not possible to abstract distinct Arab histories outside of the context of the colonisation of Palestine and the imperialist Zionist project because Arabs, like Palestinians, are the targets of that project.

The struggle in the Arab region outside of Gaza is a reflection of what is happening within Gaza. Societies must choose between becoming surrender societies or becoming new, resistant and confrontational societies. It is completely unjust that Gaza bears the brunt of this most brutal of realities, while many other Arab countries, including Egypt, receive only a warning. The fate of the region’s peoples is intrinsically linked, whether they acknowledge this fact or not. At its core, what is currently taking place is a class struggle, one that is occurring within a settler-colonial and genocidal framework. While Palestine is a universal cause – for the free people of the world, for Muslims, for the wretched of the earth, and for all those who refuse to accept a monstrous world where such horrors persist against the will of the majority – its essence and character remain, historically, materially and existentially, Arab.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

View series-

Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

Publication date:

-

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

Publication date:

-

Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Publication date:

-

Sustainability fantasies/genocidal realities Palestine against an eco-apartheid world

Publication date:

-

Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

Publication date:

-

From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024

Publication date:

-

The circus of academic complicity A tragicomic spectacle of evasion on the world stage of genocide

Publication date:

-

India, Israel, Palestine New equations demand new solidarities

Publication date: -

Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation

Publication date:

-

From the Favelas and Rural Brazil to Gaza How militarism and greenwashing shape relations, resistance, and solidarity with Palestine in Brazil

Publication date:

-

Yalla, Yalla, Abya Yala Reaching out to Palestine from Latin America in times of genocide

Publication date: