The quiet power of the Dutch Trade and Investment Board (DTIB) Where trade ministers and company lobbyists “collaborate”

Topics

Regions

For around 13 years, on the Dutch Trade and Investment Board (a body that is not familiar to most of the Dutch public) top civil servants and company lobbyists have been discussing how the government can support the country’s international trade. Minutes reveal how lobbyists and ministers collaborated in reforming fiscal and development policies in favour of private interests. It’s an example of the power of ‘quiet politics’ of company lobbyists in the Netherlands, calling into question the country’s image as an exemplar of liberal, consensual corporatism.

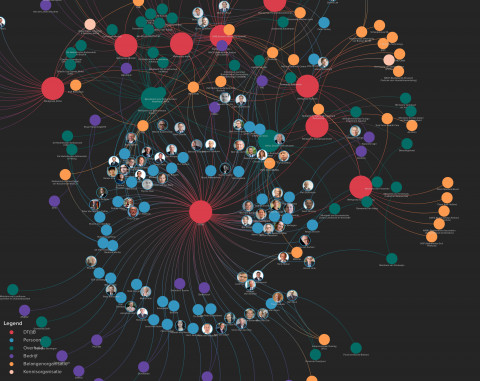

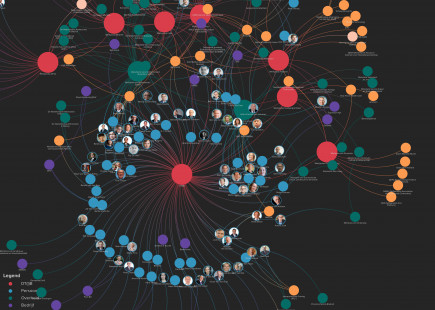

https://kumu.io/PlatformAuthentiekeJournalistiek/dtib

The following summarises a series of articles on the Dutch Trade and Investment Board (DTIB) written by Bas van Beek, Alexander Beunder and Jilles Mast of the Platform Authentieke Journalistiek. Follow The Money published the articles. The research was co-funded by SOMO, TNI and Muckracker.

Dutch politics has a reputation as inclusive and consensus based – bringing different stakeholders like employers and trade unions (social corporatism) together. But only top cabinet members and business representatives were selected for the little-known Dutch Trade and Investment Board. The central issue on its agenda for the past 13 years has been government support for Dutch companies in their international business, through subsidies, fiscal policies, trade missions, economic diplomacy and development aid expenditures.

The minutes of the meetings Platform Authentieke Journalistiek requested reveal a convivial atmosphere inside the DTIB; cabinet members pledging their support to private interests, business representatives complimenting them on their policies. Then Secretary of State for Economic Affairs, Frank Heemskerk (PvdA, the Dutch Labour party), introduced himself to the business representatives present at the meeting of the DTIB as “the Netherlands’ sales manager abroad” and “more than willing to develop opportunities for Dutch businesses”, in April 2007. He would later join the board of one of the companies participating in the DTIB: Royal HaskoningDHV.

The platform was founded in 2004 to establish a public-private dialogue on government support of internationally active Dutch firms. Over 60 Dutch companies and 30 trade associations, including the usual suspects Shell, Heineken and VNO-NCW (Confederation of Netherlands Industry and Employers), as well as seven different ministries have been involved over the past 13 years. The long list of issues discussed includes the controversial TTIP trade agreement, subsidies for internationally active firms, maintaining the Netherlands’ tax haven appeal and ‘modernizing’ development cooperation (from aid to trade).

Though top cabinet members (ministers and state secretaries) and well-known lobbyists participated in the DTIB, the board avoided the public spotlight and remains little known.

https://kumu.io/PlatformAuthentiekeJournalistiek/dtib

A network analysis of the members of the Dutch Trade and Investment Board. See interactive map here (Kumu).

Tax benefits, subsidies and development funds

The minutes reveal a shared enthusiasm among officials and company lobbyists inside the DTID for policies that have been criticised by NGOs, scientists and concerned members of parliament.

The minutes of the DTIB Werkgroep Vestigingsklimaat (Working Group Business Climate) reveal the business community spoke out strongly in favour of the “flagships” of the Dutch business climate. These included “the Dutch treaty network (both tax and investment treaties)”, a network notorious for facilitating tax avoidance; “the innovation tools (including the 30% ruling)”, a measure criticised for favoring mostly well-paid professionals and their employers by the Centraal Planbureau (Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis); “implementation by the tax authorities (e.g. rulings and horizontal supervision)”, meaning state-company tax agreements which lower tax burdens significantly (one with Starbucks was even criticized by the European Commission); and “a competitive fiscal climate for business” in general.

Business representatives inside the DTIB were also enthusiastic about the controversial “agenda of modernisation” for development cooperation. Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Lilianne Ploumen’s policy aims to tackle ‘extreme poverty’ in developing countries as well as to stimulate ‘success for Dutch companies abroad’ by involving the latter in ‘the development of ports and road building’. On several occasions the DTIB discussed how development aid could continue to benefit Dutch companies despite international agreements against tied aid (forcing recipient countries to spend aid on goods and services from the donor country), like the 2005 ‘Paris Declaration’. For example, at the October 2007 meeting Heemskerk stated that he “will make efforts to keep ORET [one of the largest development funds] as accessible as possible for the Dutch business community”.

Under Ploumen a part of development spending was shifted to the private sector, including Dutch businesses, while the minister simultaneously introduced 20% budget cuts in development aid. Multiple politicians, NGOs, academics specializing in development policy as well as official government evaluations criticised these reforms. In 2016, the Algemene Rekenkamer (Netherlands Court of Audit) for instance wrote that “across the board there is insufficient hard evidence concerning the value of the private sector’s involvement in development cooperation”.

Several of the fiscal and development policies, discussed within and supported by the DTIB, were criticised by NGO’s, scientists and critical members of parliament for serving private interests. Nevertheless, the DTIB does not view itself as a lobbying organisation for private interests but as an “independent” advisory body serving a general, national interest. Members use terms such as “advisory board”, “consultative body”, “discussion group” or “sounding board” to describe the DTIB’s activities, but never the word “lobbying”. According to current chairperson Thecla Bodewes (CEO of the Bodewes group) it is all about “open dialogue whereby all parties [...] endeavor to improve the competitiveness and prosperity of everyone”.

Quiet politics

The minutes reveal how closely ministers and company lobbyists cooperated over the years on multiple policy issues within the DTIB. In one case the employers’ organisation VNO-NCW, as part of the DTIB Werkgroep Vestigingsklimaat, helped write a ‘two-pager’ which the Ministry of Economic Affairs would submit to the cabinet council, the highest political consultative body in the country. The plan was to write a “positive, enthusing piece on the importance of the business climate” (the definitive letter is not public). Furthermore, the DTIB was consulted on multiple occasions by the attending ministers and secretaries of state, including Heemskerk and Ploumen, to help them prepare their policy plans, long before these were sent to the lower house of parliament. Ploumen would also ask business representatives in the DTIB to lobby parliament for support for her policy plans.

The low-profile political practices of the DTIB are similar to the three “tools of quiet politics”, as described by Oxford-professor of public policy Pepper D. Culpepper: lobbying, participating in informal advisory bodies and influencing press coverage. Especially when issues are of low salience the influence of business lobbyists through “quiet politics” increases, Culpepper argues.

Several sources suggest that the DTIB is not the only “public-private cooperation” that consults with ministries behind closed doors, which calls into question the reputation of the Netherlands as an exemplar of liberal, consensual corporatism. According to Culpepper, informal working groups “in which managers have a preeminent voice, and in which unions have no voice at all” have a significant role in Dutch politics.

Dutch economist Bas Jacobs observes that the existence of “organisations all over the place lobbying and influencing policy with no democratic mandate whatsoever” causes “a great deal of dissatisfaction among Dutch citizens”.

“It’s unclear on what basis political decisions are made,” says Jacobs.

Still no transparency, despite calls from members of parliament

For the time being the government refuses to provide openness about the DTIB and similar advisory bodies that exist far from the public eye. When we approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a freedom of information request (Wet Openbaarheid van Bestuur) for the DTIB documents, civil servants warned us they would black out significant parts of them. What’s more, the DTIB ceased recording the minutes of their meetings after our request, now writing only very brief “action reports”.

Since the numerous publications about the DTIB on the online platform Follow The Money, several members of parliament have asked cabinet members about the lack of transparency surrounding the DTIB, its successor (since 2018 the board has been replaced by the International Strategic Board (ISB-NL)) and similar advisory bodies.

In answer to a parliamentary question from Renske Leijten (SP, the Dutch socialist party) requesting an “exhaustive overview” of comparable advisory bodies like the DTIB, the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Sigrid Kaag responded: “Providing an exhaustive overview would entail considerable exertion by civil servants and I don’t consider that opportune.”

To Leijten’s question about the cessation of taking minutes by the DTIB/ISB-NL, Kaag indicated that “sensitive business information has to be taken into consideration and it has to be safeguarded that discussions within the ISB-NL can be conducted as open as possible”.

This evasive answer occasioned MP Mahir Alkya (SP) to submit a motion requesting that the government create a transparent process for the selection and appointment of members of the ISB-NL. Alkya is of the opinion that this advisory body should not only represent the interests of major companies, as it will influence, among other things, trade missions and economic diplomacy. His motion was supported by only 51 of 150 members of parliament (all from opposition parties), hence rejected.