Ukrainian agriculture in wartime Resilience, reforms, and markets

Regions

Agriculture stands as the cornerstone of the Ukrainian economy, providing sustenance for a significant portion of the population. Ukraine's fertile lands, favorable climate, and investment climate have not only nourished its people but also fueled food exports to Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Yet, the dynamics within Ukraine's agriculture sector are complex, with large-scale agribusiness and family farming sharing the landscape.

Before the war, agriculture was thriving, but the Russian invasion has brought disruption and challenges to the sector. The scramble for resources and government support between big business and family farmers continues, raising questions about the future of Ukrainian agriculture. As Ukraine navigates its path toward recovery, join us in exploring the intricate web of issues affecting this vital sector and the potential impacts on global food security.

Photo credit: the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

Agriculture is the central pillar of the Ukrainian economy and a major source of livelihood for about one third of the Ukrainian population. The abundant fertile land, suitable climatic conditions, and a relatively favorable investment climate have made Ukraine able not only to feed itself, but also to provide food for millions of people in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and other countries. Before the war, agriculture was one of the fastest growing sectors in Ukraine (with an annual growth of 5-6%), contributing 10,9% of GDP and providing 17% of domestic employment by 2021.

However, agriculture has also been an area of tension in Ukraine, where two different modes of production – namely, large-scale industrial agribusiness and family-based farming – have been co-existing over the years. Agribusiness controls 53.9% of arable land and contributes to 54.5% of Ukraine's gross domestic agricultural output, primarily specializing in the production of grain and oilseeds for export. The remaining share, 46.1% of total agricultural product, comes from a diverse set of small and medium-sized family farms and rural households that cultivate 45.5% of the land, producing potatoes, vegetables, fruits, grain, dairy and meat products for personal consumption and sale in domestic markets.

Despite the important role of family-based agriculture for domestic food security, the interests of family farmers and rural households are often overlooked by Ukrainian policy makers, who prioritize big business in their vision of economic development. Many agricultural and rural development programs are de jure aimed at supporting various food producers, but the de facto beneficiary is agribusiness, which receives about 60-70%1 of state agricultural subsidies and monopolizes the industrial agri-food value chain.

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has severely disrupted food production and trade in Ukraine, jeopardizing Ukrainian and global food security. Deliberate attacks by the Russian army on Ukrainian agriculture including the shelling of agricultural facilities and infrastructure across Ukraine, the use of landmines and burning of farmland near the zones of active hostilities, the five-month blockade of the Black Sea ports (and the reassertion of the blockade as of July 2023), and the explosion of the Kakhovka dam have all severely tested the Ukrainian agrarian sector. The export-oriented agribusiness suffered the greatest losses, especially at the beginning of the war. Meanwhile, family farms and rural households, despite extreme difficulties, were able to adapt to harsh conditions and provide food to the Ukrainian army and people.

Various measures have been undertaken by the Ukrainian government and its international allies to support food production and trade during the war. These, among others, include the reduction of certain taxes, tariffs and quotas, and developing new storage facilities and overland routes to export Ukrainian agricultural commodities. A continuous assessment of damage caused by the war to agriculture and the environment is carried out by Ukrainian government agencies, as well as independent national and international expert organizations. This assessment laid the foundation for the plan for the post-war recovery and development of Ukraine, which was presented in Lugano, Switzerland on 4-5 July 2022, and a year later, on 21-22 June 2023, was discussed by the world leaders at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in London, UK. However, Ukrainian civil society and academia are concerned that these measures are likely to benefit export-oriented agribusiness, leaving family farmers and rural households on the sidelines.

The war has not stopped the tensions between large and small agricultural producers in Ukraine. On the contrary, it has exacerbated them. Russia invaded Ukraine in the midst of a land reform aimed at lifting a moratorium on the sale of farmland that had been in place since 2001. Despite calls from concerned academics, NGOs and family farmers, the government has not halted the reform. Many policy makers hope that liberalization of the land market will boost investments in Ukrainian large-scale agriculture and generate budget revenues from agri-food export needed to rebuild the country after the war (before the war, the agricultural sector accounted for 45% of export earnings). At the same time, due to Ukraine’s commitment to join the EU, the Ukrainian government is now supposed to revise the rules and regulations with respect to agricultural and rural development to comply with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (which should in theory imply less support for large-scale export-oriented agribusiness and more investment in rural development programs and commercialization of family farming).

Bimodal agricultural structure: agroholdings and family farms

The co-existence of large industrial and small household farming in Ukraine has a long history. In early Soviet times, the land and property of peasants were expropriated in favor of collective and state farms (kolhospy and radhospy), where the rural population was employed as wage laborers. However, the planned economy was unable to provide the population with sufficient food, and subsidiary farming on household plots was permitted throughout the Soviet period.

This small-scale food production was seen by policy makers as having the potential to develop into the Western model of commercial family farming after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Then, a land reform was initiated which distributed agricultural land to former collective and state farm workers who received titles to specific plots of land (a so-called “pai” which means a (land) share in Ukrainian). However, all the necessary production inputs and enabling conditions for farming (capital and machinery, know-how, upstream and downstream markets, the rule of law) either disappeared with the breakdown of the collectives or were in the early stages of development in the chaotic market environment of the 1990s. Only a small number of landowners had the capacity and/or willingness to establish commercial family farms. Most of the population instead rented their land back to the former kolhospy and radhospy, the vast majority of which were reorganized into market oriented agricultural enterprises.

In the early 2000s, Ukrainian land became the object of financial interest of domestic and international investors, including Ukrainian oligarchs and transnational corporations, who invested heavily in large-scale industrial agriculture. Conceding to public opinion and also to prevent land concentration and land grabbing, the government of Ukraine introduced a temporary moratorium on land sales in 2001, which has been extended multiple times over the past 20 years (read here on the Land Question in Ukraine). The moratorium, however, did not halt the concentration of land: the reorganized collective and state farms were merged into larger agglomerates – so-called agroholdings – that extended their monopoly power over the entire value chain i.e. from production to storage, distribution and export.

Today, there are about 15,600 agricultural companies that control 53.9% (18 million hectares) of Ukrainian arable land by leasing land from the rural population. Approximately 40% of all agricultural companies are incorporated into agroholdings, which are the largest land holders in Ukraine. The top 10 largest agroholdings control 2.6 million hectares of agricultural land, which is 8% of all arable land in Ukraine. The landbank of the largest agroholdings are roughly 500,000 hectares (see Latifundinst report on the top 100 land holders in Ukraine). The source of financing for agroholdings is diverse. Some agroholdings developed mostly (at least initially) based on domestic sources of capital, while some are part of transnational corporations. A number of Ukrainian agroholdings have attracted financing through public offerings of their shares on international stock exchanges2, while additionally benefiting from funding provided by international financial institutions such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Finance Corporation. Although agroholdings have invested heavily in strategic and financial transparency, Corporate Social Responsibility and stakeholder engagement, rare but high-profile corruption scandals, such as in the case of UkrLandFarming and Mriya, have left a stain on the reputation of these agricultural giants in Ukraine.

There is no clear definition and classification of family-based farming in Ukraine.3 Different agencies provide different information about their size, quantity, and agricultural output. According to the Institute for Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, there are 31,800 registered family farmers (fermerske hospodarstva) and 3.9 million rural households (osobyste selyanske hospodarstva), but the actual number may be higher.4 Family farms have an average size of 50 to 100 hectares, which is relatively large compared to the EU average farm size of 17.4 hectares. Family farmers cultivate about 15% of arable land in Ukraine and produce 8.7% of domestic agricultural output. Some rural households function as commercial family farmers (the so-called odnoosibnyky), others – as subsistence-oriented food producers. Rural households produce 37.4% of domestic agricultural output by cultivating 30% of farmland in the country (they are quite heterogeneous in terms of land use: 85% cultivate from 1 to 5 hectares, 9% - from 5 to 10 hectares, and 6% - more than 10 hectares). Family farmers and rural households together produce 95% of potatoes produced in Ukraine, 85% of vegetables, 80% of fruits and berries, about 75% of milk and more than 35% of meat. Their production methods are more socially and environmentally sustainable when compared to large agribusiness and are carried out in accordance with local traditions and practices.

Despite the important role of family farmers and rural households in ensuring domestic food security, their interests are often overlooked by the state that largely follows the idea of “big is beautiful” and aligns itself with big business (many state authorities have direct or indirect ties to large agribusiness). Over the years, various programs have been initiated to support different forms of agriculture in Ukraine, yet their implementation is often influenced by large business interests. Thus, Mykola Stryzhak, the honorary president of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, argued that it is not the law, but the so-called "telephone principle" that determines who benefits from state support for agriculture:

A law adopted by Verkhovna Rada [the Ukrainian Parliament] may not be implemented. But if someone “from above” called on the phone – God forbid not to fulfil! Compulsory! […] The banks were “advised” not to give credits to unreliable farmers. Unreliable farmers are those with less than 500 hectares.5

The cancellation of the moratorium on land sales is one of the most controversial and politically sensitive reforms. Proponents of an open land market argue that this will increase the transparency of land-based relations, allow for more efficient farming, and let landowners receive higher prices for their land. Opponents fear that the creation of an open land market without proper support programs for smallholders will lead to the further concentration of land in hands of large agribusiness, displacement of private farmers (as they cannot compete for land with big business), environmental degradation (due to industrial farming methods), as well as further depopulation of Ukrainian villages. A public opinion survey conducted in 2019 by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, together with the Kiev International Institute of Sociology, showed that only 24% of respondents were positive about the opening of the land market, the majority - 58% - were negative.

Nevertheless, on 31 March 2020, the Verkhovna Rada adopted amendments to the Land Code, which determined the stages for the cancellation of the moratorium. At the first (transitional) stage, which started on 1 July 2021, one individual (not a legal entity) could buy up to 100 hectares of farmland. The transitional period was designed to allow family farmers and other smallholders to buy the land first and give access to the market for larger companies afterwards. After 2024, both individuals and legal entities will be allowed to purchase up to 10,000 hectares of land. For now, the law prohibits foreigners and foreign companies from buying farmland, something that can change only with a national referendum - however, there are several loopholes in the legislation, such as the possibility of dual citizenship, which allows foreigners to participate in the land market.

Photo credit: the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine /

The impact of the war on different agricultural producers in Ukraine

As of February 2023, Russia’s war in Ukraine has caused a total damage of 8.72 billion USD to Ukrainian agriculture, with aggregate losses of 31.50 billion USD, according to the World Bank estimates. The damages include the partial or complete destruction of machinery and equipment, storage facilities, livestock and perennial crops, as well as stolen inputs and outputs, and agricultural land that requires surveyance, clearance and restoration. The aggregate losses include production losses, such as unharvested crops, lower production volumes, higher production costs and lower selling prices of export-oriented commodities such as wheat, barley, corn, and sunflower seeds. In addition to this, the Kakhovka catastrophe caused 25 million USD in direct damage to agriculture, leaving almost 600,000 hectares of farmland without access to irrigation. In total, about 30% of Ukrainian farmland is currently not cultivated due to being occupied or unsafe for farming.

In addition to the direct impact on agriculture, Russia's war in Ukraine has a devastating impact on the environment, soil and water quality, which will affect agricultural development in the long term. According to the Ecoaction Centre for Environmental Initiatives (a Ukrainian environmental NGO), “explosions from aerial bombs and artillery shelling, mined territories, destroyed heavy military equipment, leakage of oil products, burned areas from fires, and landslides have become the main markers signaling a powerful impact on soil resistance to pollution, bringing with it severe socio-economic consequences, both locally and nationally” (see Ecoaction’s report on the impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine on the state of the country’s soil and the interactive map of negative environmental damages caused by Russian aggression since 24 February 2022).

Although both types of agricultural producers face severe challenges, it is large-scale industrial agribusiness that accounts for the largest share of war-related losses. Large agricultural facilities, fields and infrastructure are often targeted by Russian missiles (see satellite images of farm destructions). Frequent Russian attacks on Ukrainian power plants pose an existential threat to Ukraine’s industrial livestock and poultry sector, which, as with similar production in other countries, is extremely dependent on electricity supply. For example, a critical situation – which almost became an environmental disaster – happened in May 2022 at the Chornobayivska poultry farm (Europe's largest poultry farm) in the Kherson region, where more than 4 million chickens and about 700 thousand young chicks died without the possibility of their disposal due to an airstrike by Russian aircraft on a local power plant.

However, the most severe problems fell to the share of export-oriented agribusiness specializing in the production of grains and oilseeds. There are many documented cases of Russians stealing grain from the temporarily occupied territories, setting fire to crops near active war zones, bombing grain elevators, or planting mines in farm fields. But the biggest damage to Ukrainian grain exports was inflicted at the beginning of the war, when the Russian navy blocked the Black Sea ports through which 95% of Ukrainian grain exports used to be shipped abroad. This completely paralyzed Ukraine's export-oriented agriculture and created an unprecedented global food crisis.6 More than 25 million tons of grain were trapped in silos and in ports in Ukraine. Only 5 months later, on 27 July 2022, Russia and Ukraine, through the mediation of the UN and Turkey, managed to agree on the Black Sea Grain Initiative that resumed the grain exports from three key Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea – Odesa, Chornomorsk, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi. However, the Initiative solved the problem only partially (export flows of Ukrainian grain through the Black Sea were less than 50% of the pre-war level) and lasted only one year. On 17 July 2023, Russia withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Since then, only a few cargo ships carrying Ukrainian grain travelled around the western coast of the Black Sea - through Romanian and Bulgarian territorial waters - to be safe from Russian attacks.

The war – as well as other major world disturbances such as the Covid-19 pandemic - has revealed the systemic fragility of globalized neoliberal agriculture that is characterized by narrow specialization in agricultural production and depends on international trade in food, fuel and fertilizers. Not only is the destruction of trade routes and infrastructure jeopardizing the viability of Ukrainian agroholdings, but their mode of production makes them extremely vulnerable to major shocks and disturbances. Professor Olena Borodina of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine explains the fragility of Ukrainian large-scale agriculture during the early phase of the war:

The large agroholdings model has collapsed as a colossus with feet of clay. When the logistics chains were broken, even those agroholdings, whose lands were outside the areas of active hostilities, were unable to cultivate their lands. Their supply chains were destroyed. They store pesticides and seeds in warehouses near Kyiv, they have cars and tractors in another place. Their workforce is a travelling brigade – they do not hire the local population, but move their teams of professional machine operators from one region to another. When the war began, they were unable to carry on with their business, because they could not manage the logistics.7

Besides that, industrial agribusiness uses complex technologies and production methods that do not allow it to adjust easily in the absence of certain inputs, as was the case at the beginning of the war when there was an acute shortage of fuel and fertilizers, previously supplied from Russia and Belarus.

Almost 90% of enterprises involved in crop production and 60% of industrial livestock producers reported a significant or drastic decrease in revenues during the first year of the war (see FAO report on Impact of the war on agricultural enterprises in Ukraine). Some enterprises suspended part of their activities, especially in frontline regions. About 7% of all agricultural companies went bankrupt and ceased to exist, despite government programs aimed at supporting agriculture during the war. To survive, the previously monoculture-oriented agribusiness has begun to diversify its production and grow more vegetables and legumes for the domestic market, as well as invest in processing capacity so as not to depend on the export of agricultural raw materials (read here about survival strategies of Ukrainian agribusiness during the war).

Family farmers and rural households appeared to be more resilient in times of war, which is confirmed by the studies of the NAS of Ukraine and FAO’s report on the Impact of the war on agriculture and rural livelihoods in Ukraine. Local food producers are less dependent on external resources and international trade, they have their own equipment, machinery, and storage facilities, they often use organic fertilizers and local seeds varieties, they process and sell their food on local markets and via informal networks, and they depend on household/local labor. These qualities – as well as mutual support and solidarity – allowed Ukrainian smallholders to adapt to the most difficult of circumstances and produce food for their families, communities, the Ukrainian army, and internally displaced persons (see Mamonova on Food sovereignty and solidarity initiatives in rural Ukraine during the war).

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to argue that family farmers and rural households were not severely affected by the war. The disruption of value and supply chains and unpredictability of prices have repercussions on the farming population, underlining their interdependence with the country’s agricultural economy. Russian artillery attacks, the use of landmines, and the destruction of infrastructure and agricultural facilities are also occurring on the lands of family farmers and rural households, causing them to face problems similar to those described above for agribusiness, but on a smaller scale due to their relatively smaller size. About two-thirds (65%) of family farmers specialized in crop and almost half (45%) of family farmers specialized in livestock production reported experiencing war-related hardships, primarily related to shortages of fuel, seeds, feed and fertilizers, access to and high prices of electricity, as well as difficulties in selling their produce. Commercially-oriented rural households have been facing similar challenges. According to a FAO survey, a quarter of rural households experienced serious difficulties because of the war, and one in four respondents has stopped or reduced agricultural production due to the war. Other studies revealed that, to deal with food shortages and high food prices, more Ukrainians started growing their own food. Many internally displaced persons moved to rural areas, fleeing war zones or major cities that are often targeted by Russian missiles. These people often get involved in subsistence food production and help local farmers.8 Some experts argue that the war has resulted in the revival of many depopulated villages and demonstrated the great importance of family farms and rural households for food provision in Ukraine during the war.

The agricultural policy of Ukraine during the war

Most of the urgently initiated governmental programs at the beginning of the war were aimed at solving the acute problem with the export of grain and oilseeds. When Russia blocked the Black Sea ports, Ukrainian grain exporters had not yet shipped the entire 2021 harvest, and a new harvest was expected shortly. Before the war, the total capacity of grain and oilseed elevators and silos in Ukraine was about 57 million tons. Storage needs doubled in the first months of 2022, amounting to 107.38 million tons. The government of Ukraine, together with international partners and donors, tried to find ways to address this need. With the help of the FAO and foreign aid from Canada and Japan, polyethylene storage sleeves and mobile warehouses were placed in the fields to temporarily protect the grain. Some of the grain originally destined for export was sold at very low prices on the domestic market.

In May 2022, the European Commission and the government of Ukraine initiated the Solidarity Lanes to facilitate food exports from Ukraine via different land routes and through EU ports. Additionally, the temporary suspension of export duties and tariff quotas on Ukrainian agri-food products for a period of one year was implemented in July 2022 in accordance with the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU. One month later, in August 2022, the Convention on the Joint Transit Procedure and the Convention on Facilitation of Formalities in Trade in Goods were initiated to expand physical and logistical export opportunities across Ukrainian-EU borders.

These measures were made to help Ukrainian producers and exporters carry out activities in conditions of war and strengthen their position in the European market. Indeed, Ukrainian agricultural exports to the EU have almost doubled from 7,674 million USD in 2021 to 13,002 million USD in 2022, of which grains and oilseeds account for the lion's share (TABLE 1).

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In total |

22,146 |

22,200 |

27,710 |

23,541 |

|

|

EU-27 |

7,035 |

6,145 |

7,674 |

13,002 |

|

| The main exported commodities to the EU-27: | |||||

|

|

milk and dairy products, poultry eggs; natural honey |

117 |

140 |

150 |

263 |

|

|

grain crops |

2,493 |

1,671 |

1,935 |

5,190 |

|

|

seeds and fruits of oil plants |

1,526 |

1,145 |

1,479 |

3,017 |

|

|

fats and oils of animal or vegetable origin |

1,464 |

1,746 |

2,363 |

3,332 |

|

Middle East |

3,895 |

3,543 |

4,935 |

3,907 |

|

|

East Asia |

2,361 |

4,011 |

4,719 |

2,150 |

|

|

Africa |

3,294 |

2,924 |

3,658 |

1,617 |

|

|

South Asia |

2,038 |

2,183 |

2,889 |

1,035 |

|

|

CIS |

1,433 |

1,299 |

1,368 |

781 |

|

|

Southeast Asia |

1,169 |

1,174 |

1,205 |

316 |

|

|

Europe except EU 27 |

564 |

639 |

861 |

457 |

|

|

North America |

172 |

135 |

239 |

209 |

|

|

South America |

58 |

53 |

50 |

16 |

|

|

Australia and Oceania |

32 |

31 |

35 |

14 |

|

|

Others |

96 |

62 |

78 |

36 |

According to the State Committee of Statistics of Ukraine and the State Customs Service of Ukraine

* Based on operational data as of February 3, 2023

However, the increase in Ukrainian food exports to EU markets has caused tensions and conflicts in some member states. A large share of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds, which were originally intended for export to Asia, Africa and the Middle East, ended up being purchased in the EU. This was due to logistical bottlenecks, soaring prices for transporting it further outside the EU, broken contracts with original buyers, and in some cases “shady practices” that allowed some local actors in Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia to benefit from the sale of Ukrainian grain in local markets. The flow of (relatively cheap) Ukrainian grain to Eastern and Central Europe depressed local prices and left local farmers unable to sell their crops. In April 2023, farmer protests broke out Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, initiated primarily by large farmer organizations9 and had nationalist-populist overtones. To respond to farmers' unrest and pursuing their own political agendas, the governments of the affected countries introduced temporary bans on Ukrainian grain in April 2023, which the European Union was forced to adopt at the European level and kept in effect until September 2023. The Ukrainian government filed a complaint at the World Trade Organization against Hungary, Poland and Slovakia after they banned grain imports from Ukraine for the second time following the lifting of EU restrictions in September 2023.

Besides addressing trade and export issues, the Ukrainian government has made a number of amendments to the national legislation to guarantee domestic food security during the war. The Law on Food Security in Wartime was adopted by the Ukrainian Parliament in April 2022 to solve the problem with land lease agreements. Due to the chaos and destruction of the war, outmigration and unavailability of landowners, and lack of financial and administrative resources, many farmers were unable to renew their land leases agreements. The law extended all lease agreements automatically by one year. It also set the amount of rent (maximum 8% of the normative monetary value of land), simplified land registration in local administrations, and offered free provision of state/community land for private farming.

In May 2022, the Land Regulation under War-Time Conditions was passed to facilitate the lease of state and public land to accommodate evacuated businesses and the temporary relocation of population groups. Several state-led programs have been initiated to relocate agricultural enterprises from war zones to relatively peaceful areas such as in the Transcarpathia, Lviv and Chernivtsi regions. In the Lviv region alone, more than 300 locations are designated to receive agricultural enterprises.

To support grain producers, the government of Ukraine has suspended import tariffs for materials used in grain storage and simplified the rules for registering agricultural machinery and trucks. Furthermore, the state loan program, "Affordable loans 5-7-9%", which was previously only intended for micro and small farms to offer them credits at 5%, 7% or 9% interest rates, has now been expanded to cover more enterprises, including medium and large agribusinesses. Within this program, agribusiness could receive up to 90 million UAH (2.4 million USD) in lending at 0% to 9% interest rates to implement investment projects or refinance debt. This program was financed by The World Bank’s Program-for-Results aimed at accelerating private investment by both large and small businesses in Ukrainian agriculture. However, in practice, family farms below 1,000 hectares were unable to participate in this program because of the lack of time and resources small farmers had to apply for funding, as well as certain informal barriers (according to a survey of representatives of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners conducted by the NAS of Ukraine in March 2022).

A special program for supporting Ukrainian smallholders in times of war was implemented by the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine with financial support from the European Union (Production Grant Scheme). It includes a payment program of 3,100 UAH (84 USD) per hectare for farmers with up to 120 hectares in ownership, as well as assistance for cattle, reaching 5,300 UAH (143 USD) per head for farms with up to 100 head of cattle. There are also grant programs for horticulture and greenhouse farming that offer farmers subsidies for planting vegetables, fruit, and other greenery on new plots up to 25 hectares, as well as for the construction of a greenhouse up to 2 hectares.

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine has been developing mechanisms and guidelines that should simplify the procedure for applying for compensation for damage in the agricultural sector but, at the time of writing, such mechanisms and guidelines were not yet available. While waiting for these guidelines, Ukrainian farmers and agribusinesses have instead had to independently collect evidence and apply to various government agencies, such as the State Emergency Service, the State Ecological Inspectorate or the State Water Agency, depending on the type of damage. This is a time-consuming and highly bureaucratic procedure that takes farmers’ time away from their day-to-day activities and is, therefore, more likely to be carried out by agribusinesses that have trained personnel for such work.

On 23 June 2022, Ukraine received the status of a candidate for the European Union. There were no special requirements in the field of agriculture for obtaining and maintaining this status, except for continuing the reforms in accordance with the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU (ratified in 2014). As of the end of 2022, overall progress in the implementation of the Agreement in the field of agriculture is estimated at 60% (lower than in other areas of the economy and social life) and includes policy adjustments in the field of product quality assurance and standardization of agri-food trade, restrictions on the use of genetically modified organisms, and support for the development of organic agriculture. These measures are welcomed by entrepreneurial family farmers looking to enter the EU market. However, standardization and registration may hamper the informal economy of food production by rural households and discourage some smallholders from producing food.

Overall, the agricultural policies currently pursued by the government of Ukraine are an emergency response to extreme circumstances and have proven effective in supporting large export-oriented agribusiness, which suffered significantly in the first year of the Russian invasion. However, the policies are less effective in helping smaller food producers deal with the hazards of war.

Photo credit: the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine /

The land reform since February 2022: Arguments for and against

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the Ukrainian government restricted access to state registers and cadasters, thereby temporarily closing the land market. In May 2022, the government issued the war-time regulation concerning the register of land ownership, and the land market gradually resumed operation, except in temporarily occupied territories and war zones.

Before Russia’s war in Ukraine, the liberalization of the Ukrainian land market aroused heated debates. The main supporters of continuing land reform as planned - that is to allow for land sales to companies in 2024, and to also allow foreign ownership of land in the future - are: the Zelensky government, economists at the Kyiv School of Economics, international advisers from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and representatives of large agribusiness. Their arguments can be summarized as follows:

Firstly, the open land market will bring significant investment not only to the agricultural sector but will also boost the economy of Ukraine as a whole. The IMF estimates that if companies (other than foreign ones) are allowed to buy land, this will increase land prices by 15.05% annually and constitute 6% of Ukraine's GDP over the next ten years. Moreover, if the land market opens up to foreigners, this will lead to an annual price increase of 19.43% and bring an additional 12% of GDP in one decade (TABLE 2).

|

|

Land Price Increase; predicted |

GDP Impact* |

Scenario name; IMF |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Closed Markets |

6.7 % |

0 % |

Backsliding scenario |

|

Closed to Foreigners |

15.05 % |

0.6 % |

Partial reform scenario |

|

Open to Foreigners |

19.43 % |

1.26 % |

Full reform scenario |

*Impact calculated for a period of 10 years, 2021-2031, and annualized. Source: IMF Working Paper, WP/21/100.

Postponing corporate ownership, including foreign ownership of land, would thus mean that the government is preventing landowners from getting a fair land price, hindering the redistribution of land from less “efficient” to more “efficient” users,10 restricting investment in the agricultural sector, and thereby depriving the state budget of tax revenues much needed to rebuild the country.

Secondly, halting reforms now will not prevent de facto corporate control over land as it already exists through various shady schemes and legal loopholes (see TNI’s longread “Offshoring prosperity. Agroholdings and tax avoidance in Ukraine”). Instead, formalized and legalized ownership of land will ensure transparency in the context of land deals and motivate large agribusiness to implement long-term investment projects. It is believed that only corporate agribusiness can bring in the capital needed to clear fields of landmines; restore transport, storage and export infrastructure; expand agricultural terminals near Ukraine's border with EU countries; and invest in the recovery of export-oriented agriculture.

The final argument in favor of continuing the land reform during the war is that reality has proven that the land market can function effectively despite the war-related disturbances. In the peaceful year 2021, when the land market was open for about 7 months, 66,000 land sales transactions with a total area of 153,000 hectares were registered in the State Land Cadaster. During the first year of war, about 53,000 transactions were concluded, covering a total area of 112,000 hectares. And in the first four months of 2023, 13,000 transactions of a total area of 26,000 hectares were registered. The average size of the land plot for one transaction was about 2 hectares.

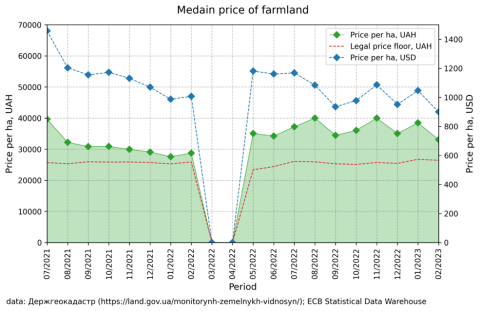

It is difficult to accurately identify the price per hectare, as it is reported only in a quarter of transactions (probably due to tax-evasion reasons, as suggested by VOX Ukraine). According to available information, the price per hectare was about 30,000 UAH/ha (approx. 1000 USD/ha) in 2021, about 35,000 UAH/ha (approx. 1100 USD/ha) in 2022, and 38,000 UAH/ha (1000 USD/ha) in 2023 (DIAGRAM 1).

Diagram 1: Reported farmland price in Ukraine 2021-2023

Source: Ukraine’s agriculture and farmland market: the impact of war

The prices measured in USD started falling in July 2022 as the National Bank of Ukraine devalued the Ukrainian hryvnia by 25%. Prices vary greatly in different regions. The highest prices were reported in Vinnytsia, Lviv, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil and Sumy regions.

Although the land market is indeed able to function during the war, the transfer of land ownership does not fully follow free market principles, but is carried out on the basis of previous (often informal) arrangements, and is influenced by the extraordinary circumstances associated with the war. According to the preliminary assessment by the Institute for Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the ongoing land sales can be explained by the following reasons:

First, some of the land deals are more likely a transfer of ownership on the basis of agreements concluded a long time ago. There are enough cases when a lease agreement was concluded with the right to purchase land immediately after a change in legislation. In these instances, payment for such lands was made earlier, but the ownership of land is legalized only now.

Second, family farmers need to buy the land they currently rent before the land market opens to companies, which will greatly increase land prices and competition for land.

The third reason for buying land is investment. This can be seen from the geography of land sales - most of the land was bought in areas with an accessible irrigation system (before the Kakhovka tragedy). The price of such land is expected to rise significantly in the future. The explosion of the Kahkovskaya dam left 250,000 hectares in the Kherson region without irrigation and reduced the value of such lands exponentially. Much of this land was used for growing vegetables by family farmers and rural households.

Fourth, there are political interests at play. There are instances when local oligarchs, through their network, buy up land to expand control over certain territories, for example, in the Kyiv region. Furthermore, representatives of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine report various cases, especially in the border areas, when foreign citizens, including Russians, buy land through nominees. Although this is not a widespread trend, such cases should be alarming.

And finally, many landowners are pursuing what could be considered to be “distress sales” i.e. they need to sell their land as soon as possible in order to make ends meet. Russia's war in Ukraine has dramatically affected the economic well-being of many Ukrainians. According to different estimations, up to 55% of the population of Ukraine will live below the poverty line by the end of 2023 (compared to 2,5% before the war). To prevent land from falling into the hands of competitors and to help their fellow villagers, farmers have to withdraw financial resources from operational activities to buy the land they previously rented.

In the autumn of 2022, the National Academy of Science of Ukraine, the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, and representatives of small agricultural producers from different regions of the country held several meetings to develop a resolution to be put to the government of Ukraine demanding, among other things, a temporary suspension of the land reform process during the war. They are concerned about the impact of ongoing land reforms on the viability of family farms and rural households. The Ukrainian Agrarian Council, which represents the interests of large agribusiness, also proposed to postpone the launch of the land market for legal entities until the end of martial law. Within the international community, it is the FAO, who, despite earlier being an important proponent of land reform in Ukraine, is now drawing attention to the risks of land reform in wartime.

The arguments against continuing land reform during the war are commonly formulated as follows:

First, many landowners are not in their place of residence and are thus unable to participate in land market transactions. According to the UNHCR, as of October 2023, 6.2 million refugees have fled Ukraine, and 5.1 million people became internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ukraine. While it is likely that the largest share of refugees and IDPs come from urban areas, certainly a percentage includes villagers and private family farmers fleeing combat zones and temporarily occupied territories. In addition to this, many rural dwellers are fighting at the front. Away from their land and villages, these people have fewer opportunities to participate in the land market transactions. There is also evidence that some land title certificates were lost or destroyed due to hostilities or urgent evacuations.

Second, almost a fifth of the territory of Ukraine is currently occupied by Russian armed forces and the line of contact between Ukrainian controlled territory and occupied territories is constantly changing. Although there is no official information on the state of affairs in the occupied territories, scattered evidence coming from these regions points to the increasing expropriation and control of land by Russian agribusiness and the imposition of land property rights in accordance with Russian legislation, including ownership of land only by Russian passport holders. Thus, there is considerable uncertainty about the status of agricultural land in the occupied territories and how the occupation will affect land ownership in the future.

Third, private farmers are not financially strong enough to buy the land they currently rent. As discussed earlier in this report, government programs to support family farmers and rural households are not effective enough, and most of them benefit large farmers only. In addition, the war has significantly worsened the financial situation of small and medium sized family farmers, and even though these farmers are less dependent on international trade and global value chains, the destruction of infrastructure, rising prices for fuel and agricultural inputs, and a decrease in the purchasing power of consumers have led to serious liquidity problems for many farms.

Fourth, war is commonly associated with instability, weakening the rule of law and transparency, which may allow for the use of so-called ‘shadow’ schemes when buying land in Ukraine. These include legal and institutional loopholes for shady and unscrupulous land transactions, especially when foreigners buy land through nominees or by acquiring Ukrainian citizenship. Even if only a relatively few such instances have come to light, family farmers speak very harshly about land reform in wartime:

What do people die for? Why do they shed blood for the Ukrainian land, if we sell the land? Who buys the land now? Not those who need it for subsistence. But those who have money, and they are often not in Ukraine.11

Even before the war, most Ukrainians were against selling land to foreigners. The Kiev International Institute of Sociology conducted a public opinion survey in 2021 that showed that if there was a referendum on foreign land ownership, 84.1% of respondents would vote against allowing foreigners to buy land. Today, despite government promises not to sell land to citizens of Russia and Belarus and companies affiliated with these two countries, Ukrainian attitudes towards foreign land ownership remain highly negative.

On 29 May 2023, a draft law “on Postponing Legal Entities Acquiring the Right to Purchase Agricultural Land Plots” was submitted for consideration to the Verkhovna Rada (the parliament of Ukraine). The bill proposed to extend by 2 years from the end of martial law the date when legal entities will be able to acquire agricultural land. However, this bill has not received significant attention in the Verkhovna Rada, and, according to experts close to Ukrainian policy makers, the second stage of the land reform process will be carried out according to the original plan, meaning that domestic companies will be allowed to participate in the land market from 1 January 2024 onwards, with the right to purchase up to 10,000 hectares.

Ukraine’s Recovery and Development Plan and the New Agrarian Policy

The Ukraine Recovery Conference – which was originally planned as the 5th Ukraine Reform Conference – was held on 4-5 July 2022 in Lugano, Switzerland, and brought together a thousand participants from more than 40 countries and numerous international organizations. The National Recovery Council, set-up by the President of Ukraine, has presented the draft of Ukraine’s Recovery and Development Plan, which covers the 2022-2032 period and is estimated at 750 billion USD (excluding funding for security and military expenditures). The plan is divided into three phases – wartime economy (2022), post-war recovery (2023-2025) and new economy (2026-2032) – and includes 850 projects within 15 national programs in various spheres of the economy and public life. With this plan, the government of Ukraine intends to rebuild Ukraine as a strong European country directed at modernization, the implementation of European integration reforms, the introduction of green technologies, enforcement of the rule of law, and enhancing transparency and accountability throughout the recovery process. These intentions are also reflected in the adopted Lugano Declaration, signed by all participants of the conference.

A year later, on 21-22 June 2023, the second Ukraine’s Recovery Conference was held in London, U.K.. World leaders, together with international financial institutions, business representatives, and civil society organizations, discussed the progress of the Ukraine Recovery and Development Plan and ways to mobilize international support for the economic and social recovery of Ukraine, primarily focusing on the participation of the private sector in the reconstruction process. About 60 billion USD of new funds have been pledged by partners in the short to medium term, of which 50 billion euro comes from the European Commission (under the Ukrainian Facility program) in the form of concessional loans, grants, and confiscated assets of the Russian Federation.

Although the Recovery and Development Plan includes more than a dozen national programs, the government of Ukraine will focus on the five most important areas in the nearest future, with agriculture being one of them. The working group, “New Agrarian Policy”, was established as part of the National Recovery Council and developed a detailed roadmap for the restoration of the agricultural sector of Ukraine.

Like Ukraine’s Recovery and Development Plan, the New Agrarian Policy is divided into three phases. The first phase, which was scheduled for 2022, was aimed at maintaining the economic potential of the agro-industrial complex12 by: 1) Ensuring food security through the abolition of certain taxes, simplified regulation, and financial support to agribusiness; 2) Building new supply routes, increasing exports, and optimizing internal logistics – those urgent policy measures discussed earlier.

The second phase (2023-2025) is aimed at restoration of the economic potential of the agro-industrial complex to the pre-war level and attracting investment in agriculture, in particular, in agricultural infrastructure. It includes various mechanisms for stimulating private investments, maintaining the purchasing power of the population through a reduction in the VAT rate for food, “unshadowing” of agricultural production (formalization of the informal food economy and registration of all producers as market operators), development of a cooperative system, diversification of logistics, and carrying out land restoration.

The third phase (2026-2032) is focused on improving the economic performance of agribusiness, diversifying export risks, and radically improving the efficiency of land use. It includes stimulating the processing of agricultural raw materials (primarily grains and oilseeds), building seed plants, supporting the domestic production of agricultural machinery and equipment, and developing the Danube River traffic as an efficient way to access Central and Western European markets. This phase also includes support for organic agriculture, implementation of the EU Green Deal requirements and further adjustment of Ukrainian agricultural policies in accordance with the Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine.

The New Agrarian Policy has been criticized by private farmer organizations, civil society, and the academic community for aiming at restoring the pre-war production and economic model of globalized export-oriented agriculture. By focusing on increasing production volumes, land-use efficiency and the development of new export destinations, the New Agrarian Policy does not take into account the interests of family farmers and rural households and calls into question the goals of sustainable and fair development. In particular, the proposed plan lacks any programs aimed at maintaining and developing localized food systems that are socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable and, as the war showed, more resilient in times of major disturbances and the key to the country's food security.

Furthermore, the plan does not answer the question of how Ukrainian agriculture should be restored in order to improve the quality of life of Ukrainian citizens in terms of providing them with high-quality and safe food and improving their access to the benefits of the countryside and ecosystem services (clean environment, ecological tourism, traditional food products, etc.). The plan is also insufficiently focused on the full implementation of the European Green Deal’s "From Farm to Fork" and "Biodiversity" strategies, which aim to develop a fair, healthy and environmentally friendly food system. These aspects are critical to address the climate and environmental crisis, in which agriculture plays a major role.

In a Recommendation Note regarding the New Agrarian Policy submitted to the Secretariat of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on 06 May 2022, the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the NAS of Ukraine argued that in order to restore war losses in the field of agriculture and rural development, guarantee domestic food security and improve rural wellbeing, Ukrainian agriculture should be reorganized based on the UN Voluntary Guidelines for Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (2012), the Global Action Plan for the UN Decade of Family Farming (2019-2028), the FAO Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (2014), the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (2018), as well as the European Green Deal: the New Farm to Fork & Biodiversity Strategies. Together with the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, academics proposed the creation of a separate working group, “Protection of the Rights of Peasants and Family Farms”, as part of the National Recovery Council to address the interests of local small-scale food producers and consumers. However, their initiative was not appreciated by the policy makers and was not implemented.

This did not stop the activists, and they continued to advocate for the interests of family farmers and rural households in Ukraine’s recovery process. In October-November 2022, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, with the support of FAO, USAID and the German NGO Austausch e.V., organized three regional round tables and a two-day Public Forum “Small Peasant Farms and Farming Households in Wartime and Post-War Reconstruction of Ukraine: Political Dialogue”. These events provided opportunities for small-scale farmers from different regions of Ukraine to express their opinion on the Recovery and Development Plan, as well as to develop a Resolution to the Government of Ukraine with concrete recommendations to different state authorities.

The resolution required the President of Ukraine to guarantee the constitutional rights of the Ukrainian people for affordable, quality, and safe food, and to secure the interests of family farmers and rural households in agrarian policies during wartime and in the post-war period. The authors of the resolution insist that agricultural policies be developed in consultation with Ukrainian family farmers’ organizations and in accordance with the aforementioned policies and guidelines outlined in the Recommendation Note. Moreover, the President was asked to approve and guarantee a 10% quota for small-scale agricultural producers in the international grain trade as part of the Humanitarian Program “Grain from Ukraine”, initiated by the President of Ukraine and implemented in partnership with the World Food Program.

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine was asked to suspend the liberalization of the farmland market in the wartime and post-war period until the legal, organizational, and financial mechanisms are created that enable family farmers and rural households to participate under fairer terms in the buying of land. The Rada was also asked to recognize the important role of family farms and rural households in domestic food security, and legally define the categories of small-, medium-, and large-scale agricultural producers. Furthermore, the authors of the resolution suggest creating a State Agency of Land Real Estate in Agriculture (Land Bank) for redistribution of farmland for development as a way to address the damage and loss of fertility incurred during wartime. The Rada was also asked to revise an unpopular law “on Agricultural Cooperation", which currently only benefits large agribusiness, and to create a favorable legal and institutional framework for family farmers and rural households in wartime and the post-war period.

The Cabinet of Ministers was asked to establish a National Agency as the central executive body to manage agricultural and rural development programs in order to increase the potential of family farms and preserve rural lifestyles, using the existing tools and cooperation within the EU-Ukraine Twinning program. The Cabinet is also asked to develop and adopt the State Program for the Development of Family Farms and Rural Households, and Food Self-Sufficiency of Citizens, Including Displaced Persons, for the period up to 2030, and to develop mechanisms for flexible assessment and reimbursement of losses (direct and indirect) from the war with adequate compensation provided to family farmers and rural households. Furthermore, the Cabinet is called upon to support the transition to agroecological farming by adapting agroecological models of BILIM (which is a knowledge exchange platform on agroecological methods) and the food sovereignty approach championed by the international peasants’ movement La Via Campesina and allies. Additionally, demands are made to protect and strengthen the production of domestic seed material and animal breeding programs, and enhance rural cooperation, including agricultural credit cooperatives, that meet the needs of small producers and are in line with EU practices. And finally, an All-Ukrainian Agricultural Census should be conducted to inform the development of a scientifically based differentiated agricultural policy.

The resolution was sent to all three levels of Ukrainian government and was widely circulated in the Ukrainian media, but no state policy adjustments have been made in response to the above recommendations. To continue advocating for private farming in Ukraine’s reconstruction programs, activists intend to organize a new Public Forum of Peasants, Farmers and Smallholders in December 2023, which will be dedicated to the implementation of an integrated approach based on respect for the rights of peasants (including land rights) in the programs of the post-war reconstruction of the agri-food system of Ukraine. In addition, they actively engage with international organizations, especially those that may influence the terms of Ukraine's association with the EU and its future membership, so that they can push the Ukrainian government to implement the paradigm of sustainable agrarian and rural development, focused on human rights.

Although the government of Ukraine is clearly oriented towards large-scale agribusiness and pursues a neoliberal agricultural policy, it has to respond to some extent to the demands of civil and academic organizations representing the interests of family farmers and rural households. Moreover, the government of Ukraine has an obligation to bring Ukrainian legislation and policies in line with EU and international standards, which should require additional efforts to improve the sustainability of Ukrainian agriculture, enhance the diversity of farming models (especially family-based agriculture), and promote rural development.

The Ukrainian government is currently facing a major dilemma: whether to continue to support the large-scale, export-oriented agricultural model, which is seen by many policy makers as a way to reconstruct and rebuild the country after the war, or to refocus on the family-based farming that is socially, environmentally and economically sustainable and more resilient in times of crisis. The political response to this uneasy question will determine the future of Ukrainian agriculture and rural areas in the years to come.