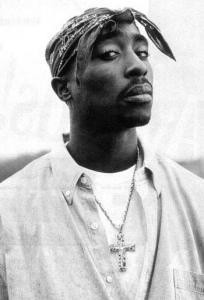

Beyond the Triangle of Emancipation Tupac’s Hip Hop Theory of Criminal (In)justice, the Pope’s Playlist, and the Prophetic Imagination

Regions

In 2009, the song Changes, by Tupac Amaru Shakur, was put on the Pope’s playlist. What is Tupac’s significance, in light of his making the Pope’s playlist and the realities facing African-Americans today in the context of the USA's overpacked prison system, the largest in world history?

Authors

In December of 2009, the song Changes, by legendary rap artist, Tupac Amaru Shakur, was put on the Pope’s playlist on the Vatican MySpace Page. This article examines Tupac’s significance, in light of his making the Pope’s playlist and the realities facing African-Americans today in the context of the USA's overpacked prison system, the largest in world history. It appears in Carceral Notebooks 3,” Summer/Fall, 2012, put out by Dr. Bernard Harcourt, Professor of Law and Criminology and Chair of the Political Science Department at the University of Chicago.

Below you find the introduction. To read the full text download it here.

For Tupac Shakur, 1971-1996,

my brother, Matthew Benjamin Ehrlich, 1974-1999,

Trayvon Martin, 1995-2012, Afeni Shakur-Davis and

Maria Reyes and the Freedom Writers

Introduction

Some years ago, I was listening to a radio documentary on Tupac Shakur about how his mother, Afeni Shakur, formerly a Black Panther, had succumbed to the crack cocaine addiction that came to plague the Black community before she turned her life around and got clean (Guy 2004). Despite my close identification with Tupac — he was born in Harlem and I in Spanish Harlem — I had forgotten this important detail. When I was reminded, totally unexpectedly and spontaneously, I burst into tears. My own parents had been long time heroin addicts and alcoholics, and my growing up, including being abandoned by them at 18 months, was complicated and difficult. Whenever I feel down, Tupac’s music uplifts me over and over, as I listen to songs like “Better Days,” “Keep Ya Head Up,” or “Unconditional Love.” Tupac, like my own kid brother, Matthew Benjamin Ehrlich, died too young, at 25 years old, both after leading lives that momentarily sparked and uplifted those in their presence during their good times. This coincidence has always made me feel an affinity with Tupac, especially since, as Michael Eric Dyson has argued, Tupac poignantly expressed both the hope and hopelessness of his generation (Dyson 2006).

The quotes that open up this article show the uncanny resonance of two of the leading figures of the Jewish and African diasporas respectively, Theodor Adorno, one of the critical theorists of the Frankfurt School, and hip hop’s Tupac Shakur. Not surprisingly, given the unique experiences of Jews and Blacks historically and in the modern world-system in particular, both Adorno and Tupac proclaimed in their own ways the “ethical message” “that the need to let suffering speak is the condition of all truth.” In a landmark article published in a special edition of Race and Class commemorating the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the English-speaking Caribbean, Jan Pieterse posited the possibility of a “triangle of emancipation” that might serve to “redress the historical balance of the triangular trade,” going onto acknowledge that the reality is at once “much less and much more than this. Much less because many in the African disapora exist as a vast underclass.... Much more because the people of Africa have joined a stream that is far wider than the waters of the Middle Passage, and have carried it further” (Pieterse 1988).

Tupac’s songs such as “Ghetto Gospel” reflected his religious inspiration and astonishing prophetic imagination, most especially in relationship to his and hip hop’s larger critique of the criminal (in)justice system and related politics of punishment, with its dogma and practice of harsh retribution, assumptions of deterrence, and embrace of so-called zero tolerance order maintenance policing. This policing strategy argues that there should be zero tolerance for even the pettiest of crimes, and that unless police stop and arrest people even for misdemeanors, that crime will spiral upwards. These ideologies and practices, despite voluminous evidence countering their assumptions and empirical validity, are at the heart of racially biased policing and hyperincarceration, disproportionately affecting young Black and Brown males (Harcourt 2001).

obedience to the law is more a function of its perceived legitimacy than deterrence

Friedrich Nietzsche, as quoted in the introductory part of this article, wrote about the system of punishment in 1887 noting little relationship between the ostensible purposes of punishment and its actual real world functions, effects and long-term consequences. In addition, mistreatment and harsh punishment by the police and in the rest of the criminal (in) justice system, by undermining people’s basic sense of fairness in treatment, delegitimize the law and law enforcement; among no group is this arguably more true than in the eyes of young men of color who are the primary victims of these practices, which arguably lead to greater law breaking. For as a host of studies have shown, obedience to the law is more a function of its perceived legitimacy than deterrence (Meares 2011; Tyler 2006, 2011; Meares, Kahan, and Katyal 2004; Rios 2011; Bobo and Thompson 2006). Thus, procedural and substantive fairness in the justice system is not only morally right, it is also arguably essential to reducing the crime, notably violent crimes, and especially lethal criminal violence, including against women, that as notable scholars have argued, is the real problem in US society, rather than crime as such (Zimring and Hawkins 1997).

George Kateb points out, in a passage that stands out all the more in the context of the recent exoneration of those US soldiers responsible for the 2005 Haditha, Iraq massacre of some two dozen civilians, including women and children, not to mention the invasion and occupation of that country, the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, and the simultaneous prosecution of Bradley Manning for exposing such war crimes today:

much of American politics...is often criminally violent and coercive (in its imperialist foreign policy and its violation of human rights abroad, including the rights pertaining to the criminal law); criminally negligent in its failure to deal in earnest with the suffering and diminishment caused by poverty and discrimination at home; and criminally corrupt in encouraging the use of various kinds of hidden but unsubtle bribery in campaigns and everyday policy-making. Rarely are any of these criminal undertakings subject to criminal punishment....The whole political system runs on crimes and near-crimes, on force and fraud abroad and by fraud at home, yet it wants to administer severe punishments as if it were cut off from ordinary criminals as one species is cut off from another....Next, I would point to the regularity of criminality and near criminality that infects the economic system (Kateb 2007: 282).

This article explores the significance of Tupac’s prophetic imagination and his hip hop theory of criminal (in)justice in light of his making the Pope’s playlist and the related challenges of the 21st century. As Michael Eric Dyson and the film Tupac, Resurrection reveal, Tupac was a complex and contradictory figure, at times tragically caught up in and sometimes glorifying the very ghetto violence, scapegoating, and misogyny that he also poignantly critiqued. Here, though, Tupac’s voice is highlighted, viewed from the vantage point of redemption. Much of Tupac’s critique, and that of hip hop more generally, has overlap with the 2000 statement of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, Responsibility, Rehabilitation, and Restoration: A Catholic Perspective on Crime and Criminal Justice, and related critiques of contemporary practices of punishment in the US (Logan 2008). The analysis put forward here is also informed by my personal experience as a survivor of domestic violence, torture, and abuse as a child, and as a former runaway and hopeless youth on the streets who became, for a time, caught up in the criminal (in)justice system. From the age of two or three I was labeled by a host of institutional actors, as a juvenile delinquent, and reading the literature in the field is like reading my own biography (Laub and Sampson 1991, 2003; Sampson and Laub 1993; Wikstrom and Sampson 2003; Keenan and Shaw 2003; Feld and Bishop 2012). I once attended a school for hardcore truants, replete with mandatory informal probation, and largely skipped junior high school, from which I was once expelled, attending only one year of high school. My involvement with the movement in its various incarnations, and school, literally saved my life, in tragic contrast to my classmates, many of whom I assume ended up in the prisons from which they were coming and going as juveniles, or worse, ended up dead. The questions explored herein are considered in the context of moving beyond the triangle of emancipation, as the prophetic imagination of the Black free- dom struggle, from Harriet Tubman to Touissant Louverture, Ella Baker, Reverend King, Malcolm X, and Tupac, Michael Eric Dyson,Tupac’s biographer, finds an increasingly resonant chord across the time and space of the global system, with hip hop now arguably the dominant form of youth culture.

Portraitphoto by FreakAleak<3

Landscapephoto is a street in East New York, Brooklyn

Pages: 155