About drug law reform in Ecuador

Topics

This page was originally published in August 2014, and last updated in June 2016.

Ecuador is going through a process of reform of its legislation on drugs and the related institutional structure. The government of Rafael Correa is pushing forward this process, which began in 2008 with a new constitution that led to the declaration of an amnesty for small-scale traffickers. In February 2014 parliament approved the Organic Criminal Procedures Code. This replaces the criminal offences section of Law 108, a piece of legislation infamous for its harshly disproportionate sentences and drive to prosecute. As a result of the amnesty and the new legislation, thousands of people were freed from prison. Al the beginning of 2015 the National Congress started to debate a proposed Organic Law on the Integrated Prevention of Drugs and the Use of Controlled Substances, a bill which seeks to replace what remains of the old law.

1. What are the current trends regarding drug laws in Ecuador?

2. What are the current drug laws in Ecuador?

3. What reform proposals and reforms to the drug laws have been made recently in the country?

4. What impact have the drug laws had on the prison situation in the country?

5. What does the law say about drug use? Is drug use or possession for personal use a crime in Ecuador?

6. Is there compulsory treatment for dependent drug users? Are there drug courts in Ecuador?

7. What is Ecuador’s stance in the international debate on drug policy?

8. What role has civil society played in the debate about drugs in Ecuador?

9. Relevant drug laws and policy documents in the country

1. What are the current trends regarding drug laws in Ecuador?Under the government of Rafael Correa and since the new constitution was enacted in 2008, a series of legislative and institutional reforms are under way, with a clear tendency towards the decriminalisation of drug users, proportionality in sentencing for drug offences, and a shift away from the focus on crime to a focus on health. From 2008 to April 2015, a series of concrete reforms have taken shape.Ecuador’s drug law was one of the most punitive in the Americas, with very harsh sentences for the crime of possession of even a small quantity of drugs. Its geographical position as a drug transit country and its proximity to cocaine-producing countries means that there is a heavy presence of different types of traffickers and levels of trafficking. It was the government of Ecuador itself that launched the wave of reforms, with strong support from academics.

The reforms kicked off in 2008, when the Constitutional Assembly approved or awarded an amnesty to people imprisoned for having transported drugs, under certain conditions. This amnesty is part of a new approach that is also reflected in the text of the constitution itself, which states in article 364:

Addictions are a public health problem. The state’s role is to develop coordinated programmes to provide information, prevent and control the use of alcohol, tobacco, and narcotic and psychotropic substances, as well as offering treatment and rehabilitation to occasional, habitual and problem users. Under no circumstances shall they be criminalised or their constitutional rights infringed.

More about the change in the approach to drugs in Ecuador in this publication by the Public Defender’s Office: Ecuador está listo para debatir el tema drogas (Only in Spanish)

The Law on Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances (Law 108) is the current law that is in the process of being replaced. It was published in the Official Gazette N° 523 on 17 September 1990, amended on several occasions since it entered into force (in 1992, 1994 and 1997), codified in 2004 and reformed in 2005. This is the law that regulated drugs in Ecuador and its objective was to “combat and eradicate the production, supply, improper use and illicit trafficking of narcotic and psychotropic substances”. The process of gradually abolishing and replacing this law is currently under way.

This law represents one of the harshest pieces of legislation in the region. Its enactment wiped out the integrated approach of Ecuador’s previous laws and national plans regarding the control and prevention of the use of illicit substances. Law 108 changed the country’s direction on these matters, shifting it away from a focus on drugs as a public health issue to give priority to law enforcement. This did not happen as a result of significant changes in the drug market in Ecuador. Instead, it was the result of the dictates of international drug control treaties and political pressure, as well as the flow of fresh funds offered by the government of the United States for drug control programmes.

Although the bilateral cooperation agreements on drug control between the United States and Ecuador are usually kept under wraps, the Ecuadorian press revealed parts of the agreement reached during the 2003 review. This agreement declared as a clear goal that Ecuador would improve its actions against illegal drug trafficking. In exchange for funding, new equipment and police stations, Ecuador would conduct aerial interception and destroy illicit crops and (practically non-existent) facilities producing illegal drugs, through joint military and police operations. The agreement included indicators to evaluate the results: the amount of drugs seized had to increase by ten per cent; the quantity of weapons and chemical inputs confiscated had to increase by fifteen per cent; and the number of people arrested and prosecuted for drug-related crimes had to increase by twelve per cent.

One of the most flagrant ways in which Law 108 contradicts the Ecuadorian constitution is the presumption of guilt inherent in the law. As well as treating drug-related offences differently to other crimes that would seem to be similarly serious, defining them as crimes punishable by imprisonment, people accused of drug offences are presumed to be guilty before they have even appeared in court.

The judicial aspects of Law 108 became the main means that allowed the Ecuadorian security forces to implement measures financed by US drug control assistance. However, Law 108 also provided for the creation of an administrative institution focused exclusively on drug issues. Specifically, it required the setting up of the National Council for the Control of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, CONSEP. The establishment of a separate institution to take charge of drug control implied a significant shift away from how the Ecuadorian government had previously dealt with drug issues.

3. What reform proposals and reforms to the drug laws have been made recently in the country?Drug policies in Ecuador are in the process of being “humanised”. The reform of Ecuador’s body of laws was launched in 2008 with the new constitution. The major step forward in doing away with Law 108 from 1990 was the bill for a Comprehensive Organic Criminal Code (Código Orgánico Integral Penal - COIP), which was brought before the National Assembly in October 2011. Articles 219-228 of this bill, which was approved in February 2014, replace the criminal offences section of the Law on Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances (Law 108).

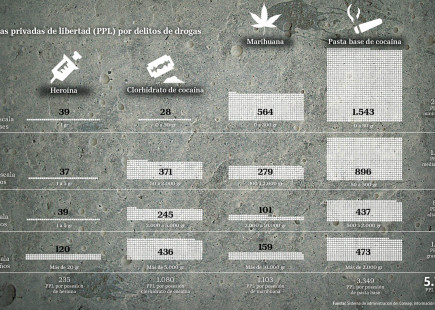

The COIP set the parameters for reorganising the criminalisation of activities that continue to be considered illegal, with the intention of making the punishment fit the crime: it differentiates between large and small-scale traffickers; grades punishments according to the role the person played in the illegal acts; and distinguishes between drug users and small-scale traffickers by means of a thresholds system (see the table in point 5). Judges are still finding it hard to apply the new law and the thresholds system as a framework of reference, and they prefer to criminalise possession plain and simple.

The growing of plants with psychoactive properties that are part of the control system is prohibited only if it is done for commercial purposes. As a result of this provision, cultivation for personal use has been decriminalised.

In January 2015, Congress held the first debate on a proposed Organic Law on the Integrated Prevention of Drugs and the Use of Controlled Substances, presented by the governing party representative Carlos Velasco Enríquez. In March 2015, the bill was discussed by the Permanent Specialised Commission on the Right to Health.

As it states in its first article, the objective of this new Organic Law is to “establish the institutional framework for the subject of drugs and controlled substances, as well as determining obligations to control them and the results of infringing such obligations.” Its approval would repeal Law 108.

The institutional structure of national agencies responsible for policy implementation would change once the bill is debated in parliament and the law approved. CONSEP (the National Council for the Control of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances) would be replaced by an Inter-Institutional Committee and a Technical Secretariat for Drugs, as new stewardship bodies responsible for implementing the law.

The proposed law also lays the legal foundations for "the classification of drugs and controlled substances for the purposes of prevention and an integrated response to their use and consumption". It understands drugs to include alcohol, tobacco, the substances classified by international treaties, synthetic drugs and substances for industrial use (glues etc), and defines the five principles that guide the application of the law: due process; shared responsibility; cross-sectoral cooperation; human rights; and sovereignty. This law is expected to be approved in the course of 2015.

4. What impact have the drug laws had on the prison situation in the country?The study Systems Overload (2010) describes in detail the heavy impact that Law 108 has had on the prison situation in Ecuador. A census of Ecuador’s prisons carried out in 2008 found that, in May that year, 34 per cent of all detainees in the country were imprisoned for drug offences. However, that same year, taking into account only the prisons in urban areas covered by the police in charge of drug control, the percentage of detainees held for drug offences increased by as much as 45 per cent.

When the types of crime for which people were charged and imprisoned each year between 1991 and 2007 are examined, the percentage of people detained for drug offences is consistently one of the highest. At several times between 1993 and 2007, nearly 50 per cent of all prisoners in Ecuador were locked up for drug offences.

In 2008, 34 per cent of the people in prison were there for drug offences, with the second largest group being people detained for crimes against property. According to the current director of the Public Defender’s Office, Ernesto Pazmiño, the sale of small quantities of drugs and petty theft accounted for the majority of these crimes. The fact that 63 per cent of all the detainees in the country were imprisoned for small-scale drug sales or theft led Pazmiño to conclude that the crimes most frequently committed in Ecuador are those that bring an economic benefit in some way. To paraphrase Pazmiño: “If I commit theft or steal something it’s because I need to survive; if I get involved in drug trafficking as a mule it’s because I need an income. So this is crime here in Ecuador. As these figures I’m giving you show, it’s a consequence of high levels of poverty, a direct consequence. What I’m saying is there’s a very close relationship between poverty, crime and imprisonment. Because the saddest thing is, when you go to the prisons, all you see are the faces of poverty.”

The percentage of women imprisoned for drug offences in Ecuador is consistently higher than that of men. Over the last 15 years, between 65 and 79 per cent of the female prison population in Ecuador were detained for drug offences. In 2009, 80 per cent of the women held in El Inca, the largest women’s prison in the country, were there for drug crimes.

With the 'amnesty for drug mules' the government of Rafael Correa sought to repair some of the harm done by the law, sending a very clear signal to the country and the world. Following the approval of the COIP in February 2014, the Office of the Human Rights Defender reviewed the cases presented in the period between the 2008 amnesty and the enactment of the new law, resulting in 1,065 people being released from jail in November 2014.

More information can be found in this article in the Ecuadorian press (in Spanish)

5. What does the law say about drug use? Is drug use or possession for personal use a crime in Ecuador?

On the subject of drug use, the contradiction between the constitution and the current law and practice is in the process of being rectified.

Article 30 of Law 108 on Narcotic or Psychotropic Substances stipulates that "the detention of drug users is prohibited.- No-one shall be deprived of their liberty for having been found under the effects of controlled substances." In Article 62, however, it criminalises the possession of controlled substances. Furthermore, Article 51 of the Organic Law on Health emphatically prohibits recreational or voluntary use of narcotic or psychotropic substances: “The production, sale, distribution and use of narcotics, psychotropic drugs and other addictive substances is prohibited, except for therapeutic use as prescribed by a doctor, which shall be controlled by the national health authority, in keeping with the relevant law.”

Thus, drug use is criminalised in practice. But Resolution 001-CONSEP-CO-2013 issued by the Ministry of Public Health and the Executive Secretariat of CONSEP now stipulates that the possession of quantities up to an established limit should not be assumed to be a crime, with the upper limit being considered the borderline between drug use and trafficking. "For the first time in this country, this resolution sets the thresholds that determine the quantity of various drugs in grams that anyone is allowed to possess or carry without arbitrarily being considered a criminal." [See the table prepared using figures from the study by Jorge Paladines, “The health response to the illicit use of drugs in Ecuador.” This study is part of the research by CEDD, “In Search of Rights: Drug Users and State Responses in Latin America.”]

Thresholds for the possession of illicit drugs in Ecuador

|

Substance |

Quantity |

|

Marijuana |

10 grams |

|

Cocaine Base Paste |

2 grams |

|

Cocaine Hydrochloride |

1 gram |

|

Heroín |

0,1 gram |

|

MDA |

0,15 grams |

|

MDMA |

0,015 grams |

|

Amphetamines |

0,040 grams |

6. Is there compulsory treatment for dependent drug users? Are there drug courts in Ecuador?

In Ecuador – as in many other countries – much of the health service is in the hands of the churches. The so-called “rehabilitation” of problem drug users is only available in four public health centres, and the rest of the facilities offering it are private or church-run. In extreme cases, the “treatment” includes torture and abuse.

The new approach to the subject of drugs places the emphasis on public health. Consequently, the system that provides care to users requires effective regulation and state control. A Ministerial Agreement of 11 May 2012 establishes the “Guidelines for the regulation of recovery centres for the treatment of people with addictions or dependency on psychoactive substances”.

In 2013, the Ministry of Public Health began to investigate the treatment facilities operating in the country, intervening in those centres operating without official permits. In the last quarter of 2013, more than 500 people were freed from clandestine “clinics”.

Even though the idea of establishing drug courts has so far not been taken up by policy decision-makers in Ecuador, some of the country’s political groups are continuing to propose that these courts be set up. The organisation Criminal Justice Ecuador (American Bar Association –ABA– and Rule of Law Initiative) actively promotes the introduction of Drug Courts, leading to several disagreements with the then Transitional Judicial Council and the National Assembly. Its proposal states:

“The Drug Courts model is a system in which drug addicts who meet certain requirements may be sent for treatment instead of continuing with the conventional criminal trial, under a mutual agreement between the prosecution and the defence and the supervision of a judge. These Courts are administrative bodies characterised by the intensive treatment of users, court supervision of that treatment, which could include mandatory drug testing and regular meetings with the judge to monitor progress, and consequences for non-compliance and failure to complete the treatment. The Drug Courts model has been very successful in reducing reoffending rates and the overburdening of the justice system caused by cases of possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use. For all these reasons I believe that our proposal should interest you” (Amado, A. (2012). “Oficio No. 95069 dirigido al Arquitecto Fernando Cordero”. Quito: Asamblea Nacional).

Information drawn from “The health response to the illicit use of drugs in Ecuador.” (in Spanish)

7. What is Ecuador’s stance in the international debate on drug policy?

Ecuador has been playing an increasingly high-profile role in the international debate and is becoming a leader on the issue at the regional level in the setting of UNASUR and CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States).

The South American Council on the World Drug Problem, which was set up in 2010 as part of UNASUR, has its headquarters in Quito. The organisation has a Plan of Action that focuses on demand reduction and alternative, integrated and sustainable development. The building of a South American identity on the issue, one of its key objectives, has been hampered by the differences in views and policies between the member states. Recently, in February 2015, it announced that it would be presenting regional initiatives in response to the world drug problem.

At the OAS Summit held in Cartagena in 2012, when the debate on drug policies broke out at the highest political level, President Correa of Ecuador was absent in protest at the exclusion of Cuba from the event but he made statements to the press supporting the new approach and acknowledging the failure of the current strategy.

During the annual meetings of the CND, Ecuador’s official statements likewise reflect a stance that is critical of the international drug control system and in favour of discussing potential reforms to the international treaties.

8. What role has civil society played in the debate about drugs in Ecuador?

The reform process in Ecuador is being driven mainly by the progressive political elite in coalition with academics. Ecuador’s Public Defender’s Office has played a very relevant role by pointing out the effects of the current legislation and orchestrating changes.

There are a few civil society organisations or social movements working on the issue, as well as groups of activists – campaigning on cannabis specifically – who influenced the design of the proposed new law, insisting on the decriminalisation of drug users.

9. Relevant drug laws and policy documents in the country

Legislative and Government Documents

Proyecto de Ley Orgánica de Prevención Integral de Drogas y Uso de Sustancias Catalogadas Sujetas a Fiscalización - December 2014

CONSEJO NACIONAL DE CONTROL DE SUSTANCIAS ESTUPEFACIENTES Y PSICOTRÓPICAS - 002 CONSEP-CD-2014 Expídense las tablas de cantidades de sustancias estupefacientes y psicotrópicas para sancionar el tráfico ilícito de mínima, mediana, alta y gran escala - July 2014

Resolución 001 CONSEP-CO-2013 - Ministry of Public Health and Executive Secretariat of CONSEP

Cooperation on drug control: Letter of Understanding between the Government of the Republic of Ecuador and the Government of the United States of America relating to the operation of the program for sensitive drug investigations in Ecuador. August 2009 (In Spanish)

Studies, surveys and other documents

En busca de los derechos: Usuarios de drogas y las respuestas estatales de América Latina , El Colectivo de Estudios Drogas y Derecho (CEDD), Mayo 2014 (Only in Spanish)

Systems Overload - Ecuador, 2010

Pardon for mules. A sound proposal - TNI Serie reforma legislativa en materia de drogas No. 1, febrero de 2009

Análisis de la ley de drogas desde una perspectiva socio-política: “Diagnóstico de la ley de sustancias estupefacientes y psicotrópicas”, Por: Carla estrella y otros, 2008

La recurrente crisis carcelaria en Ecuador. Por: Fernando Carrión M. Enero de 2006