- What are the current trends regarding drug laws in Mexico?

- What are the current drug laws in Mexico?

- What reform proposals and reforms to the drug laws have recently occurred in the country?

- How have drug laws impacted the prison situation in the country?

- What does the law say about drug use? Is it a crime in Mexico?

- How is the drug market in Mexico?

- How does Mexico positions itself in the international debate on drug policy?

- What role has civil society played in the debate on drugs?

- What are the consequences of the war on drugs in Mexico?

- Relevant drug laws and policy documents in the country

1. What are the current trends regarding drug laws in Mexico?

The arrival in December 2018 of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) to the presidency of Mexico appeared to involve a shift in the dominant prohibitionist government discourse on illegal drugs. Since 2006, Mexican drug policies have been characterised by increasing of militarisation and centralisation in order to fight the drug cartels. However, the results were poor in terms of reducing the supply of narcotics and the country experienced a rise in the number of homicides, displacements, forced disappearances and the recurrence of several human rights violations and corrupt practices.

As a consequence, the newly installed president emphasised a change in the war on drugs, focused more on reducing violence and homicides rather than going after drug lords. “Officially there is no longer a war on drugs” said AMLO. “The government’s main goal is to guarantee national security. This is essential; the other [chasing drug lords] is for the spectacle. We have lost too much time on the latter, and it has not solved anything” (

See more). Despite these and other declarations, the government soon installed a National Guard to tackle the country’s drug trafficking problem: an elite body composed of military police and naval forces, members of the federal police and the National Gendarmerie. The project was approved unanimously by 32 local congress members on the condition the National Guard kept a civil approach, to avoid the militarization that Mexican society faced during Felipe Calderón’s presidency in 2006 – 2012 (

Read more about the controversy around the National Guard).

At the same time, the new administration, part of the Morena party (National Regeneration Movement) in alliance with civil society groups, openly proposed a change in direction in drug policy, especially for cannabis. Inspired by countries like Canada and Uruguay and some states in the US, where the recreational use of marijuana has been legalised, and supported by an increasing number of Mexican citizens, the government presented a new law proposal at the end of 2018 to regulate the production, commercialisation and consumption of marijuana. It was helpful that the government faced a legal obligation to draft new legislation, after five separate Supreme Court decisions ruled on the unconstitutionality of cannabis prohibition (see further down).

Mexico was perceived in some circles to be a progressive country since it was one of the early promoters of a revision of the current UN drug control model, and pressed for a Special Session of the UN General Assembly (UNGASS) that happened in 2016. Additionally, Ernesto Zedillo, a former president of Mexico, has played a role in advocating for a change from the current war on drugs as a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, an agency that contributes to the dissemination of scientific results and evidence about the effects of drugs and drug policies, and advocates for pragmatic, rational and drug policies that respect human rights.

In public opinion, nevertheless, a small majority of Mexicans disapproves of the legalisation of cannabis, although this is decreasing. Whereas in November 2015 just 19 per cent of the population approved of legalisation, in 2016 this rose to 29% (

See more). The perception varies depending on the purpose of legalisation. A poll of 2018 shows that whereas 86.8% is in favour of legal cannabis for medical reasons, 71% said no to legalisation for recreational use (

See more).

Back to top

2. What are the current drug laws in Mexico?

In spite of the long tradition of prohibitionist policies regarding psychoactive substances, the regulation of cannabis markets in countries such as Canada, Uruguay and several states in the US has influenced in the debate around regulation of cannabis (for medical purposes) in Mexico. In 2017, the former president Enrique Peña Nieto signed a decree to legalize medical marijuana throughout a series of reforms to the General Health Law and Federal Criminal Code and appointed the Ministry of Health to design and execute public policies to regulate the medicinal use of pharmacological derivatives of all varieties of cannabis, including its content of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The Ministry is in charge of establishing rules for research and national production of medicines derivative from cannabis. The decree contemplates commercialisation, export and import of cannabis products with 1% or less THC and decriminalises farming or harvesting cannabis for medical and scientific purposes. Lastly, the Secretary of Health is in charge of reinforcing programs of prevention, rehabilitation and control of cannabis consumption, as well as treatment for people with problematic cannabis use.

Although the original regulation limited legalisation for imported medicinal cannabis products, Congress approved national production and established a time limit for the Executive to publish the regulations for the licensing process.

However, after more than a year of the approval of the law, both production and imports are currently paralysed, as the Executive refuses to publish the regulatory laws needed for granting licenses. Consequently, in practice, medicinal cannabis remains illegal.

On the other hand, in Mexico several ministries are involved in drugs control and regulation: Ministry of Security and Citizen Protection, Defence and Health. The bulk of existing drug legislation is formed by stipulations in the General Health Act and the 1994 reforms to the

Federal Criminal Code. An important change introduced by these reforms was separating drugs (and the range of crimes related to them) into distinct articles, increasing the amount of punishable offences. Sentences were increased to between 10 and 25 years for the production, transportation, trafficking, sale and supply of drugs. Sentences were reduced, however, for planting, cultivating and harvesting drug crops for the purpose of consumption. In a significant change from earlier legislation, the act states that:

“proceedings will not be initiated against a person who is not a drug addict and who is detained for the first time in possession of a quantity of narcotics included in Article 193 and when the quantity is determined to be for personal consumption [and] no penalty will be applied to drug addicts who possess narcotics listed in Article 193 strictly for personal consumption.”

The

Federal Law Against Organised Crime was approved in 1996, exponentially increasing sentences for any crime committed as part of a criminal conspiracy. This law also established the notion of "preventative detention", which was later incorporated into Mexico’s 2008 constitution. It allows for detention of up to 80 days without an arrest warrant or charge, thus allowing individuals to be detained solely on the basis of being suspected of having links to organised crime.

Although the crimes and associated sentences defined in the 1990s remain on the statute books, a change in the law (August 2009) meant they only were applied in cases involving wholesale trafficking. This

Law for small-scale selling of drugs, informally known as

Narcomenudeo, reformed Article 478 of the General Health Act and was adopted by the parliament in April 2009 and implemented as of 21 August that year. It eliminated all penalties for possession for personal consumption up to the following amounts: 5g of marijuana, 2g of opium, 500mg of cocaine, 50mg of heroin or 40mg of methamphetamines, and increased penalties for quantities above these limits, assuming the drugs were meant for sale. It also stipulated that addicts can only be subjected to obligatory treatment after their third arrest for a drug-related crime, and increased the sentences for a range of crimes, including sale of drugs to minors or selling near schools.

The law for small-scale selling of drugs also set the threshold for trafficking prosecutions at one thousand times the maximum amount allowed for personal consumption. This could result in ‘drug mules’ that swallow capsules containing more than 500g of cocaine or more than 50g of heroin, for example, being tried as large-scale traffickers subject to the harshest sentences.

Back to top

3. What reform proposals and reforms to the drug laws have recently occurred in the country?

After the elections in July 2018, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) changed the discourse about cannabis in Mexico, with more than 13 initiatives presented in the parliament aiming to regulate its market. On November 8th 2018, Olga Sánchez Cordero, secretary of the Interior, presented in the congress the

General Law for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis, an initiative that seeks to regulate the production, sale and consumption of cannabis. The bill, promoted by the president’s party Morena, establishes that adults can carry up to 30 grams of marijuana, grow a maximum of 20 plants and harvest as much as 480 grams per year (

See the proposal). The project also foresees the creation of cooperatives, which will have up to 150 members and could produce up to 480 grams a year per member. Regarding consumption, the proposed bill allows smoking in public spaces and follows the same regulations as tobacco, which implies sanctions for selling marijuana to minors. The initiative also expects the creation of the Mexican Institute for Regulation and Control of cannabis, in charge of developing the rules for production, commercialisation and consumption. Lastly, the bill also allowed cannabis production for selling with a preliminary license, as well as industrial, medical and therapeutic production (

See more).

On the other hand, Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong and Manuel Añorve Baños, members of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the former president’s political party, presented in 2018 a similar initiative to reform several articles to the General Health Law, as well as the Federal Criminal Code and the Federal Law against Organized Crime, in order to eliminate the absolute prohibition of recreational marijuana. The bill hoped to remove the authorisation from the Secretary of Health to cultivate, harvest, possess, transport, use and consumption of cannabis with recreational purposes. The project also increases the personal possession limit from 5 to 28 grams but does not specify the amounts allowed for cultivation, instead but leaving them to the General Health Law. The commercialisation, selling and distribution of any cannabis product, however, remain illegal (

See more).

These initiatives received a strong impetus from the decision of the Supreme Court of Justice that

declared the absolute prohibition of recreational use of marijuana unconstitutional in October 2018. The Supreme Court ruled positively about two specific rights related to legal protection of cannabis use, a decision that reached sufficient jurisprudence to force Congress to modify the law related to marijuana. As explained

in an article by Jorge Hernández Tinajero, drug policy specialist, jurisprudence is created when the same court rules in the same sense and on the same subject on five consecutive occasions. Once jurisprudence is established, any other court in the country must resolve in the same way in any similar case that falls within the scope of its jurisdiction.

The decision of the Supreme Court set a precedent in the cannabis law in Mexico and has several implications: first, it orders the Federal Sanitary Risks Commission (COFEPRIS) to grant a permit to the complainants (who requested a permit from this agency) to grow cannabis under certain conditions; second, it establishes the unconstitutionality of some sections of national laws dealing with cannabis; and finally, it states the limits of the State's legal action against any private decision of adults, as long as they do not affect third parties. Hernández states that: “The new jurisprudence thus protects all those adults who decide to use cannabis privately, regardless of the purpose. Since the plaintiffs explicitly asked to grow their own plants, arguing that they refused to obtain cannabis in the illegal market, the Court determined that they could grow them in private spaces, and proof that the cultivation has no commercial purpose, it is carried out between adults and does not affect third parties”.

According to one author, the most important aspects of the Supreme Court resolution are: 1. the Court establishes that the complete prohibition of cannabis in Mexico is unconstitutional; 2. recognises that the Mexican State guarantees – and must protect – the free development of personality and personal autonomy as inalienable rights of adults; 3. the law regarding cannabis in Mexico has not changed, despite the Court’s resolutions, which means that any act related to the cannabis plant remains illegal and constitutes a crime. Consumption is allowed, nonetheless, but any act inherent to it is and constitutes a crime; 4. the new jurisprudence, however, means that if one cultivates for oneself, and within the limits established, but for some reason is surprised by the authorities, the judge will have to rule in favour of the grower and leave him free with everything and his plants, since the State protects the aforementioned legal rights: the right to personal autonomy and the free development of personality; 5. The Court’s decision opens the door for users to have an alternative to the black market, which represents a challenge for the current legislation that will have to be modified given that nowadays it is more dangerous to cultivate, even for oneself, than to buy in illicit circuits. “In other words, the law itself now encourages what it is intended to fight”; 6. the jurisprudence does not establish that cannabis cultivation must be just individual, so it opens up the possibility of forming crop associations in the future.

The Supreme Court verdict, however, does not allow the commercialization or the use of other psychotropic substances, and forced the government to introduce new legislation through Congress before October 31st 2019.

Consequently, members of the Morena party presented the General Law for Regulation and Control of Cannabis in October 2019, but due to a lack of consensus within the parliament, the due date was postponed until April 30th 2020. Because of the Covid-19 emergency, the deadline was again extended and on November 19th 2020 the Parliament finally approved

the adult-use marijuana legalisation bill. This bill allows users to carry up to 28 grams and grow a maximum of four plants per person, and 6 per household. This new legislation also regulates the hemp industry but does not address medical cannabis. Although approval by the lower legislative chamber is pending as of December 15, 2020 and needs to be signed by the president López Obrador, the law has been criticised for its social justice implications; the regulation benefits large companies to the detriment of small scale growers and consumers by limiting home growing. The bill also keeps the prohibition approach by criminalising users that exceed the allowed amounts, and perpetuates the illegal market (

see the critiques).

On another topic, on August 2019 a judge issued

two court decisions that allowed two people to have an authorisation "for personal and recreational use" of cocaine. This decision, however, does not imply the legalisation of cocaine consumption but has been perceived as a first step towards decriminalisation of different substances.

Back to top

4. How have drug laws impacted the prison situation in the country?

Although the past administrations put a big effort into applying rigorous and strict legislation, the use and commercialization of illicit drugs has increased in the past decade. As noted by the

Report of the Global Commission of Drug Policy 2018, prohibition has not only been inefficient but has empowered and enriched organised crime, boosted levels of violence and increased the imprisonment rate. According to the report

La política de drogas en México: causa de una tragedia nacional, in despite of the changes introduced on marijuana consumption and other substances throughout the Narcomenudeo Law (that eliminated all sanctions for established amounts for personal use and focuses on combating the retail drug trade), Mexico still prosecutes and imprisons people who use drugs, as well as women who carry illicit substances without criminal records and small-scale sellers (who later get replaced by others). A

report by Mexico Unido contra el Delito shows that in 2014, around 410,758 people were incarcerated for drug crimes (41 percent of the total jailed), from which 307,133 (75 percent) were simple possession or consumption. Another study showed that in 2016, 43.8 percent of arrests at the federal level were related to drug crimes (

See Sobredosis carcelaria y política de drogas en América Latina)

This situation has brought about an increase in the number of people in jail and has contributed to an overcrowding problem in Mexican prisons that in 2016 were already more than 10 per cent over-full (

See further data). According to data from 2016, the simple possession of illicit drugs represented the fourth most committed crime with nearly 5,700 people arrested, compared to drug trafficking that was the tenth-place offense with around 3,200 people prosecuted. Most recent data also shows an increase on crime incidence rate related to drugs; in January 2019, for example, the number of alleged drug crimes was 5,661 cases, compared to 4,862 cases for the same period in 2018, which represents an increase of 16.4 percent. And a comparison between December 2018 – when the new government came to power – and January 2019, the crime incidence rate related to drugs also increased 22.77 percent, higher than the crime incidence in total which increased by 9.03 percent (

See the Crime Incidence Report).

A particular situation has been the increase of women incarcerated for drug offences (See graphic). Data from 2014 shows that 44.8 percent of the women in jail were for drugs crimes. More women get involved with drug-related crimes due to financial difficulties or pressure from their partners who are already involved in the activity (

read more).

According to Carlos Zamudio, a drugs expert, the growth in the numbers responds to a government policy of increasing prosecutions that has not necessarily translated into a reduction neither in the drug market nor of consumption. One of the reasons for the latter, notes Zamudio, is that the behaviours that are pursued – especially possession – are not only committed by narcomenudistas, but by simple users, which results in the police wasting efforts to stop and punish regular users instead of dealing with real narcomenudistas. Furthermore, the Narcomenudeo Law has become an excuse for the police to establish what Zamudio calls “institutionalised extortion”, in which the majority of the victims are young users caught with a certain amount of cannabis who are asked for a bribe in order to avoid prosecution.

“When a user or his surroundings smell like cannabis, the police stop him for a routine check. In case that they find enough (or supposed) evidence, the person can be sent to the Public Ministry by the alleged crime of drug dealing. This implies – in addition to the loss of confidence in the authority by the users – the legal possibility that some police officers detain users for possession of drugs because they did not accept or could give a morbid, or as a way to avoid persecution of narcomenudistas that could corrupt them. In any way, by presenting alleged narcomenudistas the police justify its work” explains Zamudio (

Read the complete article by Zamudio).

Another reason behind the overpopulation is due to the use of preventive detention that is established by the constitution to be applied in what are considered serious offences, such as public health offences, the category drug consumption falls into. According to the 194 article of the Federal Code of Criminal Procedure, every offense related to drugs is considered a serious felony; therefore any person accused of committing this kind of offence has to go to prison even if she is innocent. As mentioned by Luis María Aguilar in the report

Statistics on the state penitentiary system in Mexico, the preventive detention has resulted in “exorbitant costs to maintain precarious, overcrowded and dangerous prisons, criminal schools for offenders of little malice, connivance between prosecuted and sentenced, separated families, truncated projects and lives wasted for those convicted without conviction, those absolved after years of litigation” (

see Report here). According to the same report, as in the rest of Latin America, Mexico has an estimated 40 per cent of its inmates in jail with no sentence.

Due to the overloaded conditions, the government has tried to decongest the penitentiary system by releasing non-violent offenders sentenced for simple possession of cannabis throughout the National Law of Criminal Execution. However, up to 2017 just 38 cases benefited from early release.

Back to top

5. What does the law say about drug use? Is it a crime in Mexico?

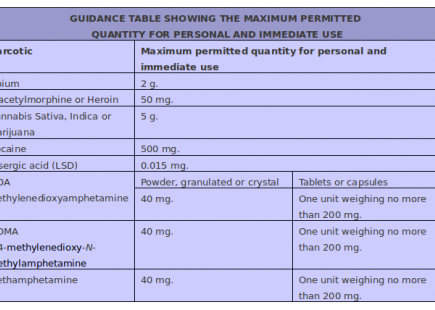

It is not a crime to use psychoactive substances in Mexico, but possession of a drug for the purpose of using it is classified as a crime. Even so, possession does not carry a prison sentence if the quantity held does not exceed the upper limits established by the Guidance Table (see below), and providing the person is not carrying drugs in the places stipulated in Article 475 of the General Health Law (schools, prisons, etc).