How to Kill an Entire Country The Legacy of the Sanctions against Iraq

Regiones

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the US invasion and occupation of Iraq. While much attention has been given to the devastating effects of the war, little is known about the sanctions regime inflicted against the Iraqi people, which predates the 2003 invasion by over a decade. In this longread Doa Ali delves into its painful legacy.

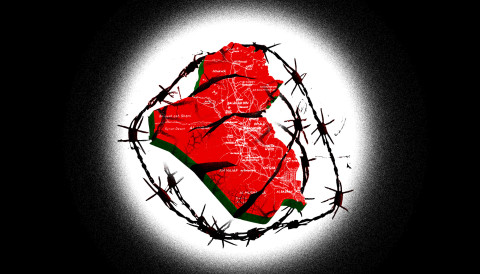

Illustration by Mohammad Shehadeh

Introduction

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the US invasion and occupation of Iraq. While much attention has been given to the devastating effects of the war, little is known about the sanctions regime inflicted against the Iraqi people, which predates the 2003 invasion by over a decade.

Iraq is a case in point of how the US has captured the UN Security Council’s sanctioning capacity using it to impose its own ‘rules-based global order’ and further its imperialist interests, regardless of the human cost.

The sanctions unleashed on Iraq on 6th August 1990 and imposed until the 2003 invasion were deeply cruel and inhumane. People could no longer acquire basic food products or medical supplies. This led directly to starvation, chronic child malnutrition and other severe health conditions, and death. Conservative estimates indicate that at least two million people died as a direct result of the sanctions.

In this longread Doa Ali delves into the painful legacy of dismantling a country, its economy and its society, through US led criminal and murderous sanctions, which as Doa affirms were designed ‘to kill an entire country’.

This is a translation of an article published originally in Arabic by media outlet 7iber. We have translated it into English for our readership to shed more light on the true reality of sanctions - far from being an effective tool to stop wars, they should be more accurately understood as weapons of war.

U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Rick Sforza/@USArmy/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

The United Nations (UN) imposed sanctions against Iraq from August 1990 until the United States (US) invasion in March 2003, marking the beginning of a new era with the US emerging as a global power. The imposition of comprehensive sanctions on a country with a population of approximately 20 million at the time showcased US power, unilateralism and its ability to leverage international bodies to legitimise its policies. Simultaneously, the sanctions on Iraq served as a paradigm that has been replicated and developed several times, becoming one of the most significant weapons of this new era.

Such sanctions had never been possible before. During the Cold War, the power balance within the UN Security Council (UNSC) prevented the consensus necessary for such an agreement, and alternative options were available for countries facing the risk of sanctions. While the case of South Africa, often cited as a positive example of utilising economic sanctions, garnered significant international participation, the sanctions against apartheid did not go so far as to severely hinder its ability to import goods or dismantle its infrastructure.1

During the latter half of the 20th century, third-world countries drew their strength from their anti-colonial movements and the wave of independence after World War II. Additionally, semi-socialist alternatives provided better development solutions for newly established nations that had endured centuries of impoverishment. However, these countries experienced a substantial decline in power in the new global order they were thrust into. They not only faced violent repercussions, including extensive social and economic ‘structural adjustments,’ but also lost their ability to navigate between the political spheres of the East and West. This vulnerability was exposed in the international balance of power like never before, highlighting their diminished influence within the UN, despite being the very countries that had endowed the organisation with its central role in international affairs.2

The Western narrative of the Cold War victory portrayed the new international order as more stable and peaceful, with the West assuming the role of safeguarding global security through the UN.3 However, it was within this supposedly protective framework of global stability and adherence to international law through collective decision-making and nonviolent means that sanctions emerged. In hindsight, three decades later, we now realise that this new order was far from peaceful or collective. Instead, the risk of war intensified, often camouflaged by humanitarian interventions, and the concept of collectivism merely became a rebranding of American influence. Furthermore, as in the case of Iraq, the new tools employed turned out to be just as destructive and violent, with the impact of sanctions qualifying as a form of genocide.

Revisiting these sanctions over 30 years after their implementation serves as a poignant reminder of the immense impact of this recent history, which continues to cast its shadow on the present day. It signifies a new era of destruction, epitomised by the occupation of Iraq. Equally important is the need to comprehend how sanctions have been utilised as tools of coercion to establish and maintain the current global order. Furthermore, it is vital to grasp the implications of the diminishing capacity to employ sanctions.

EU/ECHO/Peter Biro/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The United Nations (of America)

On 6th August 1990, four days after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, the UNSC passed Resolution 661. This resolution prohibited the importation and exportation of goods to and from Iraq, except for medicines and limited provisions of foodstuffs "in humanitarian circumstances." However, the enforcement mechanisms established to implement the sanctions effectively blocked Iraq from importing any food, even though it relied on imports for 70% of its food supply at the time. Within a year of the sanctions being imposed, Iraq's exports plummeted by 97%, and imports declined by 90%.4

The resolution was passed without any objections and adopted by 13 votes, with Cuba and Yemen choosing to abstain—which was no coincidence. In her book, Invisible War: The US and the Iraq Sanctions, Joy Gordon argues the US offered almost every developing country within the UNSC ‘concessions’ in exchange for their favourable votes on the resolution. The US used its influence over the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to provide loans to Jordan, Egypt, Turkey and China while also extending economic aid to Colombia, Ethiopia and Zaire.5 As for Yemen, the US offered to support Palestine by appointing a Palestinian as a UN ombudsman in Israel. Upon Yemen's decision to ultimately abstain from voting, a US diplomat remarked to the Yemeni ambassador, “That will be the most expensive 'no' vote you ever cast.” Just three days later, the US cancelled a US$70 million aid programme designated for Yemen.6

The resolution determined the establishment of a committee within the UNSC, comprising all council members, to oversee the enforcement of the sanctions, commonly referred to as the '661 Committee'. Initially, the powers of the 661 Committee were restricted to reviewing reports on the measures taken to implement the sanctions and requesting additional information on the progress made. However, over time, the committee's authority expanded, granting it ultimate control over all goods entering or leaving Iraq. The committee also identified imports eligible for humanitarian carve-outs, including those facilitated by UN bodies, and assumed the responsibility of interpreting all UN resolutions pertaining to sanctions on Iraq.7

The 661 Committee was designed to grant US control over the sanctions regime. It operated on a consensus-based decision-making process, where any member had veto power. Moreover, all sessions were closed, and some members were often not provided with meeting agendas. Despite the large number of export and procurement contracts that the committee was tasked with ratifying, it consisted of only 15 members representing the member states in the UNSC, leading to significant delays. Moreover, the committee did not provide justifications for its decisions to prohibit the import of certain goods, simply responding with "did not get approval". Throughout its tenure, the committee had no well-defined criteria for disapproval.8

During the early months of the sanctions, the US, along with a few Western countries led by the UK, opposed the implementation of the humanitarian carve-out that permitted food imports as stipulated in the resolution. A UN memorandum documents the dispute within the committee regarding a request from Bulgaria to export a shipment of infant formula in early 1991. The US argued that only severe food shortages, such as a large-scale famine, fell within the scope of the humanitarian carve-out, emphasising that food itself was not considered a humanitarian necessity. Until March 1991, the US maintained that allowing Iraq to import food "undermined the purpose of Resolution 661". Subsequently, the commission issued a decision authorising the import of food with prior notification and humanitarian goods subject to the committee's approval, based on the recognition of humanitarian concerns faced by the entire Iraqi population.9 Throughout the period from the initiation of the sanctions until that point, Iraq managed to import only 10,000 tonnes of grain, approximately equivalent to its requirement for a single day.10

The US, supported by the UK, found ways to work around that decision. Using the pretext of barring industrial inputs, they disapproved the importation of materials necessary for food production and preservation. These materials include aluminium for packaging food products, plastic for juice bottle production, salt used in the leather industry, and white cloth for shrouds, claiming that it could enhance the Iraqi clothing industry. Syria requested permission to grind wheat for Iraq due to the destruction of a significant number of its factories and its inability to import industrial machinery, but the US representative on the committee opposed the request, arguing that the focus should be on capacity building within Iraq.11

The US used the dual-purpose argument to justify rejecting several contracts. Under the pretext of military and civilian use of goods, the US prohibited the import of several items, including generators, water purifiers and construction materials, which were crucial for the restoration of Iraq’s destroyed infrastructure. Additionally, a long list of prohibited items was enforced. This list even included children's vaccines due to concerns that weakened viruses could be extracted for the production of biological weapons. Other items such as eggs were banned because they could potentially be used as incubators for viruses, toothpaste because fluoride could be used in the production of chemical weapons and atropine (a drug necessary for surgeries requiring general anaesthesia) due to concerns that Iraqi soldiers could use it as an antidote to nerve agents in battle.12

Consequently, Iraq could barely import any goods in the first five years, often citing reasons such as industrial input, dual-purpose nature, or non-essential humanitarian status. In 1995, the UNSC passed Resolution 986, which established the Oil-for-Food Programme (OIP) to allow Iraq to export a portion of its oil production in exchange for importing its essential goods.13 Despite the UN Secretary-General's Envoy acknowledging that this arrangement would only fulfil less than a third of Iraq's essential human needs, the US continued to pursue a similar approach within the committee. However, the language changed and instead of rejecting import contracts, the committee delayed them for months even years pending approval. By May 2002, the value of the withheld contracts reached USD 5.5 billion, with the US alone responsible for withholding 90% and the UK approximately 5%. The remaining reservations were imposed jointly by both countries.14

During the summer of 2002, the extensive list of prohibited and restricted items imposed by the US generated global outrage. In response, the UNSC approved a new mechanism for reviewing import contracts, which introduced a categorisation system of ‘prohibited’, ‘requiring approval’ and ‘permitted’ goods. Moreover, a new UN committee was formed to review the contracts. As long as the contracts were no longer under US control, most of them were swiftly approved, resulting in a significant decrease of withheld contracts by 87% by October of the same year.15 However, the damage had already been inflicted after 12 years of enduring the crippling siege.

The design of the 661 Committee granted the US significant power to shape the sanctions regime. Resolution 661 did not have a specific time limit, which meant that lifting the sanctions required a new UNSC resolution, and such a resolution could always be vetoed. As a result, the sanctions would remain in effect until the US decided to lift them.16 While the stated objective of the resolution was the withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait, the US soon introduced a complex set of additional conditions. These conditions were challenging for Iraq to meet, and it was difficult for the UNSC to assess compliance.17 The US also began using human rights lingo, emphasising that lifting sanctions is directly linked to the Iraqi regime ending the violations committed against its own people. It is worth noting that just four years prior to the imposition of sanctions, the US voted against a UN resolution condemning Iraq for its use of chemical weapons against Iranian soldiers. Before the first year of sanctions was even completed, the US made it clear that the new condition for lifting them was regime change.18

However, a regime change consensus was not achieved at the UN. Hans von Sponeck, who served as the UN Assistant Secretary-General and UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq at the time, and was in charge of the oil-for-food programme in the late nineties, commented, "There was some barking, but there was no biting."19 Madeleine Albright, the U.S. Ambassador to the UN in the mid-nineties, expressed her indifference to the UN "barking" by stating, " We will act multilaterally when we can and unilaterally when we must."20

Arlo Ringsmuth/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Dismantling society

We will return you to the pre-industrial age.

- The US. Secretary of State, James Baker, 9 January 1991.21

The sanctions regime was both a prelude and a complement to the 1991 war. The US-led coalition has left Iraq in an apocalyptic state,22 and the sanctions have ensured that the country will not be out of crisis for decades.

In just 42 days, coalition forces carried out 118,000 airstrikes, dropping more than 170,000 bombs weighing nearly 88,000 tons, including thousands of depleted uranium bombs, over 800 targets, mostly from Iraqi infrastructure and industrial facilities. This amount of explosive power was equivalent to seven Hiroshima atomic bombs. In addition to tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers who were killed by shelling in the desert, burned with napalm in trenches, thousands buried in mass graves, and some even buried alive, an estimated 113,000 Iraqi civilians were killed before the end of the war, 60% of whom were children.23

The US targets included a huge number of civilian facilities that had nothing to do with the invasion of Kuwait. These encompassed power plants, water purification facilities, reservoirs, sewage treatment plants, bridges, roads, railways, train stations, bus stations, telephone networks, wireless installations, oil wells, pipelines, refineries, food, textile, and car assembly factories, universities, schools, hospitals, dispensaries, places of worship, archaeological sites, as well as nearly 20,000 houses, apartments and housing units. The total cost of the destruction in Iraq was estimated at USD 190 billion.24

The war technically destroyed all the essential elements necessary for a modern society to sustain life, leaving the Iraqi government incapable of performing its daily state functions. Subsequently, the sanctions were imposed, further hindering any attempts to address this dire situation. Immediately after the end of the war, the government initiated an infrastructure repair campaign, which achieved "unexpected success" within three months. However, these efforts were far from sufficient. By the end of the war, Iraq's electricity generation capacity had plummeted to less than 4% of its previous levels, access to potable water had decreased by 75%, and half of its telephone lines were irreparably destroyed. The absence of electricity meant that medicines could not be refrigerated, hospitals could not operate effectively, and the lack of water purification and sanitation facilities led to the rampant spread of waterborne diseases. Additionally, the distribution of food heavily relied on trucks and functional roadways. Recognising that this catastrophic situation persisted throughout most of the embargo, the extent of the calamity inflicted upon Iraq becomes evident."25

The combination of war and sanctions resulted in the undoing of nearly half a century of development and improvements in living standards. By the late 1980s, Iraq had achieved one of the highest per capita food rates in the region, with a high enrolment rate of children in elementary education. In the late 70s, Iraq even received a UNESCO award for its successful campaign aimed at raising the female literacy rate to 85%. Furthermore, 93% of the population had access to healthcare, and significant progress had been made in eradicating communicable diseases through widespread vaccination.26

However, towards the end of the 90s, quality of life indicators experienced a significant decline across all levels. The Iraqi government's food ration system, recognised by the FAO, served as the only safeguard against widespread famine. Shockingly, in the first year of sanctions, approximately 11,000 Iraqis succumbed to starvation. The average calorie intake per capita plummeted by almost half, and the rations provided were deficient in vital nutrients and proteins.27

By 1998, one-third of Iraqi children suffered from chronic malnutrition and weighed only a fraction of the expected weight for their age. Additionally, an alarming 70% of Iraqi women suffered from anaemia.28

It came as no surprise that diseases associated with malnutrition and transmitted through water and food, such as cholera, typhoid and malaria, as well as cancers, especially leukaemia, were spread as a result of radioactive contamination from depleted uranium and other toxic chemicals used during the war.29 Iraq's devastated health sector was ill-equipped to deal with such crises. Refrigerated drug stocks were destroyed, and domestic production of medicines, which constituted 25% of total consumption before the war, ceased. The capacity to utilise medical equipment was severely limited, and even basic medical supplies like cotton, gauze and syringes became inaccessible. By 1995, the number of surgeries performed had declined to less than a third of pre-war levels. In 1998, one-third of hospital beds had to be closed, and over half of the medical equipment was non-functional.30

All this coincided with violent economic and social collapse. The prohibition on oil exports during the initial five years of sanctions deprived Iraq of its most essential source of hard currency, leading to a severe devaluation of the currency, rampant inflation, and a GDP contraction of nearly one-eighth. By 1995, the value of the Iraqi dinar had depreciated by 5,000%, resulting in an average monthly income equivalent to two US dollars. Food prices had skyrocketed by 4,500%, and households' purchasing power was only 5% of what it had been before August 1990.31 As state revenues dwindled and wages lost their value, one-third of the Iraqi army soldiers were laid off, over 12,000 teachers resigned, and many professionals fled the country. Desperate families resorted to selling furniture, electrical appliances, clothes and even parts of their homes, such as windows, doors and concrete blocks. When there was nothing left to sell, theft, prostitution, and violent crime surged rapidly."32

As a result, a terrible amount of people died. In 1999, the Iraqi government declared that two million Iraqis had died from sanctions, half of them children. UNICEF noted that at least half a million children under five have died due to sanctions.33 The number of deaths from sanctions caused great controversy, as the US had long questioned Iraqi estimates – considering that a country so broken is supposed to maintain accurate statistical capabilities – as well as UN estimates.34 But the most conservative of these estimates paints an extremely grim picture of what happened.

Public domain

The dawn of the end of the siege

After famously remarking in 1996 that the death of half a million Iraqi children was an acceptable price for weakening the Iraqi regime, Albright later expressed regret for what she recognised as a stupid statement. However, as Gordon points out, it was no more than a public relations blunder—clearly, the loss of lives was deemed worthwhile. US officials were neither naive nor uninformed, and the blockade of Iraq, despite the outcry it generated, was not a failure from their point of view; on the contrary, it was a resounding success. The sanctions served as a perfect crime, achieving maximum effectiveness at a minimal cost. As a result, it has become a model that has been repeatedly employed against whoever deviates from the American rules-based world order.

The US alone imposes more sanctions than all other countries and institutions combined, against a long list of targets ranging from Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, Russia, Syria, China, North Korea and Lebanon. Since the blockade of Iraq, US sanctions are no longer directed at countries only, they go after institutions, companies, individual officials, and even ordinary citizens in countries that may not necessarily have bad relations with the US. And once sanctioned, escape from the blacklist of the world's most powerful country is not easy.35

The example of Iraq reveals that US sanctions are indistinguishable from UN sanctions. Throughout the past three decades, no other country has advocated for sanctions to the same extent as the US. Gradually, the US has assumed the UN's role in sanctioning nations, no longer maintaining the ‘international’ cover. For instance, a recurring event is the annual vote at the UN General Assembly against the US embargo on Cuba, which has intensified since 2019 and endured for thirty years. This vote consistently follows a familiar pattern: an overwhelmingly supportive resolution, minimal abstentions and only two opposing votes from Israel and the US.

The sanctions imposed on Iraq are not only significant for understanding the pinnacle of American hegemony but also for comprehending its decline. The recent Ukraine war and sanctions on Russia, indicate that the US is no longer capable of replicating its actions against Iraq with any country, and this applies not only to a nuclear power like Russia. The US has escalated its antagonism towards China, promoting the "either with us or against us" narrative, resulting in the emergence of the so-called affected club, consisting of a growing range of nations and communities that share a desire for a post-American world, and sometimes nothing more.

Much has been said about the West's hypocrisy since the war on Ukraine, and an increasing number of countries are distancing themselves from the influence of the US. The crucial question that arises is: what actions will these affected countries take? Will they envision and shape a new world, or will they simply sit and watch? Recognising the nature of this pivotal moment early on will allow nations to seize this historic opportunity. And no one is better prepared to navigate this path than those who steadfastly resisted submission to the US at the height of its power.