Resisting Disaster Capitalism through Mutual Aid in Puerto Rico

Temas

Puerto Rico’s inspiring community-led responses to hurricanes, climate change and a deep economic and political crisis rooted in its structural relationship with US empire, offer important insights for social movements worldwide fighting against new forms of neoliberal authoritarianism.

Photo credit Casa Pueblo.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic struck Italy. Schools, universities and offices closed, the government introduced a curfew, many people lost their jobs, and panic started to spread. I was in my second year of college and suddenly was stuck at home with no lessons, no social activity, and a lot of concerns. The government didn’t know how to tackle the socio-economic crisis that the pandemic was generating, while the first people to react were university students and youth political collectives, who founded Volunteering Emergency Brigades (BVE) in Milan and other Italian cities. Based in a small town near Milan, there were no youth-led political organisations, however my neighbour Shirin Reza Elahi and I had been talking about the political conjuncture through the hedge that separated our homes. So one day we took the decision to join the BVE and found a brigade in our town. At first, we helped by answering phone calls from people who felt afraid and alone, or were stuck at home without any help or who had lost their jobs and were left with no money. Then, we created solidarity food collection boxes in many of our town’s buildings, encouraging people to donate or take items according to their needs and possibilities. Finally, we organised a 24/7 food distribution program to those most in need, thanks to food donations and collaboration with local markets and the other brigades. Five years have passed since that moment, and Lupo Rosso, the brigade we founded, is still active with popular education projects, food distributions, a free legal desk, community events and political activity. Many young people joined us, we expanded our organisational capacity and created ties with the silenced and discriminated local Filipino migrant community. Lupo Rosso managed to change the social structure of our town, drawing the annoyed attention of local politicians, who did not expect new constituencies to coordinate, organise autonomously and critique political leaders’ faults and deficiencies, especially not in a time of crisis. However, the sense of unity and community, the collective power of Lupo Rosso stemmed precisely from that crisis, from the sense of urgency, the necessity of action that awakened us from our capitalist, individualistic lives.

Lupo Rosso was a turning point in my political formation, as it introduced me to the concept of mutual aid. I experienced the power of grassroots organisation and mutual aid as imaginative and practical tools to build a more just reality. Since then, I have explored how marginalised and racialised communities – such as the Black Panthers, Occupy Sandy and indigenous movements – have used mutual aid to challenge systematic oppression and to react during critical moments. Mutual aid practices can be a radical transformative approach for social movements, as they can engage un-politicised people to organise in their community, while also involving them in a process of political formation, questioning of social systems and the creation of collective subjects involved in decolonisation and anticapitalist strategies based on solidarity. One of the most powerful recent examples, that I have got to know, is the Puerto Rican Mutual Aid Network, a group of grassroots organisations that united to respond to Hurricane Maria, which violently hit the archipelago in September 2017.

The Puerto Rican grassroots organisations’ experience of autogestión (self-management) and mutual aid shows how people can face a multidimensional crisis, creating a network of groups that collaborate to improve their material living conditions, while also challenging their colonial political system and creating international solidarity ties with other oppressed peoples.

Photo credit Centre for Mutual Aid in Bucarabones Unido (CAMBU).

Puerto Rico’s Colonial Status

Puerto Rico, originally called Borikén in the indigenous language and officially known as the 'Free Associated State of Puerto Rico', is an archipelago in the Caribbean. After being a Spanish colony from the beginning of the 16th century, in 1898 it became a US 'incorporated territory', that is, a US colony. Since the establishment of the Estado Libre Asociado (ELA) in 1952, Puerto Ricans have been able to elect their own Governor and maintain a local judicial system with its own criminal and civil codes, provided they align with US law. However, both the governor and the entire judicial system are subject to the control of the executive, legislative and judicial US bodies. Furthermore, key matters such as citizenship, immigration, defence, and foreign trade remain under US federal control. Crucially, Puerto Ricans still lack voting representation in the US Congress. Despite claims of increased autonomy under the ELA, many Puerto Rican citizens and scholars argue that the ELA still has colonial status, given the absence of congressional representation and the continued dominance of US power over the archipelago. This explains why Puerto Rico is often called 'the oldest colony in the world.'

The primary goal of colonisation is resource exploitation, and the US has extracted and used Puerto Rico's resources, labour, and strategic location throughout its occupation. The islands of Vieques and Culebra were used as military bases and training areas, especially during the Cold War, where chemical agents (later used in the Vietnam War) were tested.1 However, Puerto Ricans have also long resisted colonial rule, for example, winning the closure of the Vieques base in 2003 after years of protests. Beyond military control, Puerto Rico relies heavily on US food imports, with over 80% coming from the mainland, a direct result of colonisation and forced industrialisation that destroyed the island's agriculture.2 Politically, the US has also employed a range of repressive instruments - surveillance, defamation, sabotage, incarcerations of leaders and assassinations - against pro-independence armed and non-armed movements, through what has been called a 'regime of a colonial state of exception.'3

Furthermore, Puerto Rico has served as a US laboratory for various experiments. It was a US testing ground for economic development and political stability strategies during the Cold War, when it was promoted as a 'showcase of democracy' in contrast to Cuba. Its population has been chosen for birth-control and population-control measures, because it was a dense, poor and uneducated population that could show the social advantages of the pill, according to US officials. More recently, companies such as Monsanto4 (now owned by the German company Bayer) and Syngenta5 continue to experiment with genetically modified seeds, thanks to economic benefits like tax exemptions and easy access to water and land. Thus, Puerto Ricans have had to confront the evolving forms in which colonialism has been exerted on their territory.

A Multidimensional Crisis

Since 2016, Puerto Rico has faced a complex crisis, when it declared bankruptcy, worsening a fiscal crisis after a decade of recession. In response, Obama signed the PROMESA law, aiming to restructure the debt and enforce fiscal responsibility. It created the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB), a body comprised of seven members appointed by the US President, which can override local laws, blatantly highlighting Puerto Rico's colonial status. In 2017, the Board imposed a ten-year plan of austerity, cutting budgets for healthcare, education, and other vital services. The inability of the government to deal with the economic crisis led to an increase in political distrust. As Pantojas-García, sociologist and professor at the University of Puerto Rico claims, Puerto Ricans were navigating through a fiscal crisis as well as a crisis of 'governance, institutions, and political leadership'.6 According to the US Census Bureau, in July 2023, 41.7% of Puerto Ricans lived below the poverty line.7 Nevertheless, Puerto Rico receives less funding for Medicare and Medicaid payments than the US states, and is not qualified to receive other types of federal aid programmes.

In this context, Hurricane Maria, a Category 5 hurricane that struck the island in September 2017, amplified both the deteriorating living conditions for the population, and the climate of distrust and disillusionment with the government. The hurricane destroyed roads and buildings and disrupted water supply, energy, telecommunications networks, and access to healthcare, exacerbating the damage brought by another hurricane two weeks earlier. Aside from material damages, the hurricane also unleashed a political crisis, as neither the local nor the federal government adequately responded to the emergency. The US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the first Trump administration allocated more resources to mainland territories, such as Texas and Florida. A month after the disaster, parts of the island were still without electricity. Although the first governmental death count registered only 64 people, independent investigation estimated much higher figures related to the hurricane’s aftermath, up to at least 4,645 people, which the government initially refused to recognise.

Disaster capitalism

Disaster capitalism refers to the instrumentalisation of a natural or human disaster to approve and pass privatisation and deregulation measures, therefore prioritising corporate interests and profit-making over people’s well-being.8 Puerto Rico has been a laboratory of disaster capitalism.

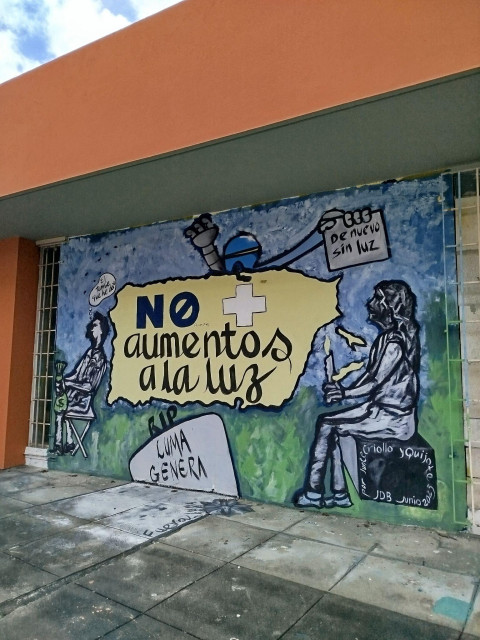

In 2018, the former Governor announced plans to privatise Puerto Rico’s Public Electric Power Authority, claiming it would ensure a better service, after the outages caused by Hurricane Maria. In 2021 LUMA, a Canadian-US company, started operating as the new power supplier in Puerto Rico, with a 15-year licence. After Hurricane Fiona in 2022, LUMA could not provide a sufficient service, leaving 40,000 people without power9 for three weeks after the hurricane. In August 2024, Ernesto, a Category 1 hurricane, struck Puerto Rico and more than 725,000 homes and shops were left with no electricity.10 The islands of Vieques and Culebra, known as 'the colony of the colony', faced almost total blackouts for days. By early 2025, the service had still not improved.11 The evidence shows that companies have taken advantage of the disaster, political instability and the need for immediate solutions to take over public services and profit without providing any relief in return.

Photo by the author.

In 2019, the local government passed Act 60, the 'Puerto Rico Incentives Code', merging Act 20 and Act 22 of 2012, which regulated tax exemptions for foreign corporations and individuals. Act 60 grants tax exemptions on passive incomes and other benefits to foreigners who acquire residency in Puerto Rico and foreign corporations that open an office in Puerto Rico. Since then, housing prices have surged, fewer houses are available to Puerto Ricans, and evictions and foreclosures have risen. Again, it is appropriate to speak of disaster capitalism because, especially in the coastal areas, the incentives attracted many foreign investors, interested in buying buildings and lands mainly for touristic purposes, which, in turn, deprive locals of access to beaches and natural areas. Short-term rentals for tourists further exacerbate the issue, as the owners displace local communities and gentrify neighbourhoods.12 Short-term rentals reduce the housing supply and increase the prices for long-term rentals and housing sales. As Alejandra Castrodad of community organisation Resilient Power Puerto Rico claimed at the UN Committee on Decolonization in June 2024, the displacement caused by foreign investors and companies 'is not gentrification but the voracious advance of settler colonialism'.13

The aftermath of Hurricane Maria, its mismanagement by government and the activation of multiple mutual aid groups prompted a political crisis. A subsequent political scandal led to the collapse of the local political system. In July 2019, a private Telegram chat, where former Governor Rosselló and other politicians discussed political issues, was leaked by the Center for Investigative Journalism. 'Telegram-gate' revealed chats filled with sexual, misogynistic, and homophobic jokes, alongside conversations that ridiculed the opposition and made fun of journalists. However, the most scandalous texts were jokes about the deaths caused by Hurricane Maria. Telegram-gate coincided with the FBI arresting six people linked to Rosselló’s administration with corruption charges for management of disaster recovery funds. Consequently, civil society organisations, political parties, solidarity groups, students’ organisations, and labour unions united in peoples’ assemblies and a national strike under the rallying cry of 'Ricky, renuncia, y llévate a la junta!' (Ricky, resign, and take the FOMB with you!). After weeks of ceaseless protest, they managed to obtain Rosselló’s resignation, a historically unprecedented event.

The so-called 'Verano Boricua' protests were not only an expression of outrage over the Telegram scandal, but a more general manifestation of weariness and rejection of the entire political class and colonial system. For Professor Pedro Cabán, this period showed that the cumulative impact of Hurricane Maria had prompted a new collective awareness to the point of fragmenting the 'colonial mentality of dependence, fatalism, and political impotence'14 that characterised Puerto Ricans. However, in 2020 Pedro Pierluisi, a former advocate for PROMESA and a legal advisor to the FOMB, was elected as Governor. This showed the limited scope of action within institutional and partisan politics in Puerto Rico, given that the root of suffering, privatisation, displacement, and forced migration is not down to a choice of a governor, but rather the structured relationship of colonial dependence with the United States.

Photo credit private source.

Puerto Ricans face a colonial institutional crisis: all aspects of the state and the consequences they have on people's lives, both collectively and individually, are affected by the crisis. It is a political crisis, in which the bipartisan system is increasingly losing legitimacy, and the empire clips the wings of any autonomous solution that could alter the legal nature of the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico; a fiscal and economic crisis, where the population is forced to migrate to the US in search of opportunities; and a crisis in resource management, responsible for the deaths of many citizens, due to the inability to foresee disasters, and the precariousness of life for Puerto Ricans. Finally, it’s a crisis of imagination: in such a hostile scenario, where worrying about one's survival and ensuring access to basic services is a daily concern, what political solution, what resistance can develop?

Mutual Aid response

Disaster capitalism shows how disasters provide opportunities to pursue a neoliberal agenda; nevertheless, corporations and governments are not the only actors who can take advantage of the changes generated by catastrophes. Social actors also have the agency and the capacity to mobilise people and resources. The emotional effect generated by the disaster can be transformed into opportunities for social change. In Puerto Rico, from 2016 to 2019 and until today a new wave of grassroots solidarity has mobilised many people both in the archipelago and within the diaspora, activating mutual support and self-management groups. The connection between crises and mutual aid is not new. Most present-day examples of mutualistic experiences have been in a post-disaster context (i.e., Occupy Sandy that responded to the 2012 hurricane in New York, or the worldwide mutual-aid grassroots organisations that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic), when the urgency of solidarity becomes stronger, and the inability of the state to manage the situation becomes more evident. In fact, mutual aid has been described as 'a highly politicised, prefigurative phenomenon which links non-hierarchical organisation to structural critiques of disaster, capitalism, climate change and disease, which tend to impact unequally on the most oppressed groups in society'.15

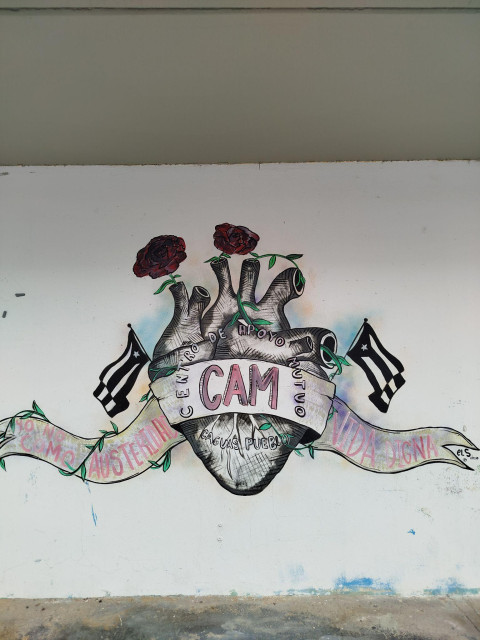

In post-Maria Puerto Rico, the necessity of rebuilding homes and streets, providing essentials and medication to the elderly, and helping each other overcome the trauma led to the creation of the Mutual Aid network. The need for communal spaces, internet access, activities for children in abandoned rural areas, and support for local agriculture and small traders solidified this grassroots solidarity, transforming it into established organisations that continue to operate beyond immediate relief efforts. The grassroots organisations participating in the network agreed on the principles of mutual aid, solidarity, community sovereignty, sustainability, and justice. At the forefront of the network were the Centros de Ayuda Mutua (CAM, Centre for Mutual Aid). The first CAM was born in Caguas days after Maria, when activists of the university collective Comedores Sociales and community members decided to occupy and rescue an abandoned building, first organising meals for the residents, then evolving into a centre with physical and mental health services, a food cooperative, summer camps and community-based events. Based on this experience, many other CAMs were formed throughout the island, often occupying rescued schools that were abandoned because of privatisation.

The network included and collaborated with pre-existing and/or different organisations from the CAMs, such as transfeminist and queer collectives like Taller Salud, agroecological initiatives, community-based sustainable development projects such as IDEBAJO, and groups more oriented to institutional politics. Caminando la Utopía is a project born after Hurricane Maria that practices community healing to treat trauma response through acutherapy and other methodologies. Even though the Network is not as active as it was during its first years, more organisations are emerging following its same principles, such as Apoyo Mutuo Agricola PR, that provides agroecological support to small farmers, organises health care labs, and investigates the policies that hinder agricultural development in Puerto Rico. As happened after Maria, after Fiona too, groups such as the Brigada Solidaria del Oeste, and Taller Salud organised direct economic aid, volunteer home reconstruction groups and workshops, as well as emergency kits distributions.

In response to the blackouts and the privatisation of the energy supply system, community-based groups strived to decentralise and democratise energy generation, promoting solar panels to guarantee energy supply independently of LUMA. Casa Pueblo is a community-based organisation founded in 1980 that focuses on energy self-sufficiency and the cultural affirmation of an alternative development model; they envision energy independence as a decolonial route, as Arturo, the son of the founders of Casa Pueblo and one of the leaders of the project, explained. After Maria, Casa Pueblo started a solidarity and sustainable development project called '50% Con Sol' (50% with the sun), which aims to install solar panels over the roofs of houses and small businesses, in order to reach a goal of 50% of total electric energy produced by the sun. The project defines itself as a self-management initiative, because it tackles the issue of energy dependency at its roots, replacing it with bottom-up, endogenous, clean and renewable sources. It is decolonial in the sense that it breaks with the dependency model, making citizens less reliant on fossil fuel companies and less impacted by adverse weather conditions and the apagones caused by malfunctions of the privatised energy system, encouraging a sustainable and effective 'model of self-decolonisation'.

As regards the housing crisis, the local reaction to this 'disaster opportunism'16, as Puerto Ricans activists call it, has been the development of a movement to reappropriate urban spaces and disused buildings, in an attempt to keep the residential neighbourhoods alive, and develop nearby and accessible services and activities. Close to the CAM in Caguas, there are multiple buildings managed by Urbe Apié, a grassroots organisation created by residents in 2015 with the purpose of returning abandoned buildings to the community in the form of social projects and public spaces. Among other initiatives, they now have a community art gallery, a secondhand clothing boutique, a community vegetable garden and other initiatives all in the same neighbourhood, which they are trying to transform into the Caguas 'social neighbourhood', with the collaboration of CAM Caguas.

Guiding principles

Two words or concepts mark the mobilisation in Puerto Rico: mutual aid and autogestión. Dean Spade, a US law professor and intersectional trans-feminist activist, defines mutualism as the collective coordination to meet the needs of all, with the understanding that these needs arise from a system that is unable to meet them.17 Autogestión (self-management) is a political process based on participative democratic consensus and popular political education, with the awareness that power is meant to satisfy the community’s needs without reliance on dominant internal or external centres of power.

Mutual aid projects are often confused with charity programmes or government assistance. However, mutual aid is, by definition, horizontalist and participatory. It doesn’t rely on professional non-profits, and it follows the community’s needs, not the goals of a programme or government regulations. A first aspect that characterises the emergence and trajectory of Puerto Rican organisations is precisely volunteer grassroots participation, which is at the core of mutual aid. This participation is driven by the urgency and necessity arising from natural disasters, but it is also a political choice, implying a specific repertoire of action. In a context of little hope, limited institutional political opportunities, and significant precariousness, Puerto Rican organisations emerge based on the needs of the community.

Mutual aid projects do not necessarily organise as traditional social movements, do not automatically imply advocacy towards authorities and do not only focus on a selected issue, but are necessity-driven and community-based. Nevertheless, they are political: awareness of the structural and systemic causes of precarious living conditions and inequalities is at the foundation of opting for action based on an alternative model of organisation. Furthermore, the very exercise of mutual aid is pedagogical, in the sense that organising among neighbours and collectively responding to their needs awakens a sense of power, agency, and imagination that naturally produces political awareness. Villarubia-Mendoza and Vélez-Vélez, Puerto Rican scholars who have studied the island’s processes for years, argue that the CAMs are striving to 'build new imaginaries through practice' that both criticise and question the government and the extractivist mode of production, and pose alternative ways of living, producing and organising.18

Photo by the author.

The consequence of mutual support and community self-management is a process of dignification, the creation of a collective subject through which anyone, not just political leaders or activists, realises they have agency, and can elaborate answers to their needs in a non-individualist way. Just as happened in my small town with the experience of Lupo Rosso during the COVID-19 pandemic, neighbours get involved in decision-making, in a counter-hegemonic appropriation of resources, and by contributing to community processes, as happened in Puerto Rico with the proliferation of CAMs following the model of the CAM in Caugas. The common thread among mutual-aid organisations in Puerto Rico is that they address, through mutual aid and self-management, the neoliberal-colonial structure of power19 as the root of the inequalities and difficulties they experience.

Intersectoral solidarity

In pursuit of solidarity, horizontality, and dignity, Puerto Rican organisations emphasise the connections between anticolonial, anticapitalist and antipatriarchal struggles. The CAMs that originally composed the Network are now working alongside other groups, each focusing on their own area of work, such as popular education, the economy, food sovereignty, health, energy independence, and the defence of public spaces. All engage communities, put participatory democracy into practice and address relevant and interconnected issues, with limited funding. The creation of mutual aid connections not only within, but also among organisations, enables the exchange of resources, practices, support, and gives the network strength. It also provides coherence to its solidarity principles, because it recognises not only abstractly, but in practice, the interdependent nature of oppressions, discriminations and disadvantages. The convergence of spontaneous solidarity and an intentional effort to achieve greater political, economic, and social autonomy recalls the theories put forth by post-Marxist philosophers Hardt and Negri regarding the concept of the multitude as an active, multifold social agent capable of producing 'new forms of life, new languages, new ethical and intellectual powers'.20

This aspect leads to another fundamental element in the landscape of social action in the archipelago, that is, territoriality. In Puerto Rico, as is common in Latin America, resistance takes on an inherently territorial character, in the sense that the first step in almost any struggle is to reappropriate local resources that have been taken and exploited for an exogenous benefit, as does Urbe Apié in downtown Caguas. Another example are the agroecological brigades who are creating an internal food growing and distribution system, avoiding exports to the U.S., as part of a food sovereignty effort, self-managing their natural resources and reclaiming their peasant and indigenous origins.

![Graffiti by @sliz.pr and @sexareo in the ‘social district’ of Caguas, near Urbe Apié and Cam Caguas. In the cartoon, the words “may the [Puerto Rican] people not die”.](/files/styles/full_width_small/public/2025-08/Graffiti%20by%20%40sliz.pr%20and%20%40sexareo%20in%20the%20%E2%80%98social%20district%E2%80%99%20of%20Caguas%2C%20near%20Urbe%20Api%C3%A9%20and%20Cam%20Caguas.%20In%20the%20cartoon%2C%20the%20words%20%E2%80%9Cmay%20the%20%5BPuerto%20Rican%5D%20people%20not%20die%E2%80%9D.jpeg?itok=VT88cFhY)

Photo by the author.

Territoriality is a crucial dimension of the struggle, because resistance can ‘simply’ mean staying in Puerto Rico, opposing occupation, gentrification, displacement and resource-grabbing by foreign actors. Resisting means fighting for dignified living conditions in the place where one was born. It is for this reason that the intersectoral solidarity of Puerto Rican organisations is extremely effective: it allows for addressing the multiple and diverse consequences that the crisis has on the supply of services, physical and mental health conditions, and the territory's resources.

In a recent interview with an activist who was among the first to organise the Mutual Aid Network back in 2017, she shared her realisation that: 'We have no strategy; we're not engaging with institutional politics or participating in the electoral process, because we're so focused on our survival—just getting water, light, and electricity to literally survive. Resistance in Puerto Rico is simply staying here, not leaving, and trying to build a life on this island'. This conversation happened right after the storm Ernesto, in August 2024, and the subsequent weeks of blockages. At times, the ability to develop strong political strategies is lacking, as daily survival consumes all energy. However, surviving isn't occurring in a selfish or individualistic manner, but rather through community-based processes of bottom-up solidarity. As Spade points out, in modern capitalist societies, which are built on patriarchy and colonialism and prioritize competition and individualism, collaboration and mutual care become acts of radical resistance.

International solidarity

The political perspective of Puerto Rican organisations is grounded in their territorial reality, but it extends beyond this, encompassing a global critical vision. The significant presence of the United States in the public, private and governmental sectors of Puerto Rico is the legacy of an incomplete decolonisation process, a condition faced by other countries of the world too, and which the narrative of a multipolar decolonised world contributes to silence. Due to the Zionist genocidal and ethnic cleansing colonial project in Palestine, this narrative is increasingly scrutinised, with the Palestinian struggle emerging as a rallying focus for many decolonial, feminist, and anticapitalist organisations worldwide. Among them are many Puerto Rican organisations that have mobilised strongly in support of Palestinians, acknowledging the numerous parallels between the colonial dynamics experienced by the Palestinian Occupied Territories and their country.

A common thread has always linked the struggle for Puerto Rican independence with the Palestinian struggle, because although the empire tries to disguise settler colonialism, occupation, and exploitation with ambiguous regimes and manipulation of international law, colonised peoples recognise the violence they endure and see it reflected in other occupied populations. As Professor Awartani claims, the constant comparison between Puerto Rico and Palestine that the Puerto Rican Armed Forces of National Liberation made between 1974 and 1985 revealed 'the essential role that geographies of imperial aggression played in efforts to denaturalize Puerto Rico’s ambiguous status in the US imagination'.21 Just as the Palestinians’ right to armed resistance against the occupying power is nowadays largely vilified by the Western world, the Puerto Rican armed struggle was also labelled as unjustified terrorist violence and repressed. Just as Israeli prisons are full of political prisoners, US prisons have also seen many Puerto Rican independence activists pass through. Just as one of the pillars of the Zionist project in the Palestinian territories is settler colonialism, in Puerto Rico—on a different scale and with a lower degree of violence—economic and financial interests are also secured through permanent settlements by foreign entrepreneurs, which force the local population to emigrate or live under worsening conditions. In both Puerto Rico22 and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, what is lacking is public recognition of the colonial occupation. Until this is acknowledged, no proposed solution will be able to justly compensate the oppressed population. Making colonial practices by oppressive states visible and connecting them can help shift the analytical lens, fostering a change in perspective.

Photo credit Colectiva Feminista en Construcción.

Recently, Comedores Sociales, founded in 2013 to eradicate hunger in Puerto Rico, supported the student-led Gazan organisation Ele Elna Elak and the community kitchen Shabab Gaza through donations and the Cooking in Gaza initiative. The latter involves a Puerto Rican activist who prepares traditional Puerto Rican dishes in refugee camps in Gaza, which highlights Puerto Rican solidarity in support of food sovereignty, which has been severely undermined in both territories through the selling of indigenous products as colonial goods, control over water, fishing, and agriculture, and the destruction of natural resources. All these actions only serve to increase dependence on the colonising nation, trapping the citizens of the colony in a cycle of reliance.

Conclusions

In the face of growing threats of economic crises and climate collapse, and a new global surge to the right, as well as the emergence of new forms of neocolonialism and extractivism, there is much to learn from those resisting capitalism and colonialism in one of the world's oldest colonies.

Through the reimagination and implementation of alternative modes of living, which align with the direction of a collective just transition, organisations in Puerto Rico are not only revealing the illegitimacy of colonial institutional authorities and opposing the global system of imperial aggression, they are also defining and affirming their capacity for autonomy and self-determination. As capitalism and colonialism expand and penetrate all aspects of life, even psychologically, resistance evolves to unite struggles against capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy. Since the modern battlefield is everywhere, resistance must also be everywhere, starting locally, as colonial conflicts stem from land theft, and growing from the bottom up through participatory democracy and self-management. However, while rooted locally, looking beyond one's own borders is also crucial to build horizons of justice for all. Mutual aid can be an articulator of local and transnational solidarity and direct-action.

Puerto Rican organisations, despite challenges of managing non-hierarchical dynamics, lack of funding, precarious living conditions, and the drop in enthusiasm due to the end of the acute moment of crisis, have shown flexibility and resilience. They have been able to meet community needs by addressing the economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and a series of poorly managed climate disasters, as well as structural problems such as energy and food dependency, and they continue to evolve. Thus, the Puerto Rican approach offers valuable insights for social movements worldwide, but especially in other non-autonomous territories, in their fight against current hegemonies. Furthermore, as it was for me, the Puerto Rican experience can be an inspiration to all people who feel the need to take action and do not know how to begin.