The Green Pakistan Initiative Green capitalism and rural dispossession in Pakistan

On 11 July 2025, as monsoon rains flood Lahore, Pakistan launched the army-backed Green Pakistan Initiative—corporate farms and six new canals in Punjab. Sold as “modernization,” it’s triggering evictions of small farmers, fresh water disputes with Sindh, big Gulf investments, and a growing protest movement led by figures like “Zulfiqar Junior.”

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Executive Summary

- The Green Pakistan Initiative is a military-led programme launched in 2023 to promote corporate farming through large-scale irrigation projects and foreign (mainly Gulf) investment in agriculture. It is presented as a comprehensive response to Pakistan’s economic and ecological challenges, promising mechanised farming and green development. However, despite this language of sustainability the Green Pakistan Initiative reflects longstanding patterns in Pakistan’s political economy, where the military holds a dominant role in governance and controls vast areas of land.

- This article places the Green Pakistan Initiative within a historical trajectory that runs from colonial ‘canal colonies’ to post-colonial mega-projects, and shows how development schemes have worked to strengthen elite control over land rather than redistribute it. The programme marks a shift from agricultural landlordism to corporate-led agribusiness supported by key state institutions and foreign investors.

- Legal and policy changes under the Green Pakistan Initiative allow for the long-term leasing of state land to military-run enterprises and Gulf-based agribusiness corporations. These arrangements give them secure access to Pakistan’s agricultural resources while communities who have farmed the same land for generations now face eviction. Environmental risks and damage, such as groundwater depletion, destruction of mangroves, and water scarcity, fall on rural populations, while much of the profit leaves the country.

- The Green Pakistan Initiative hides its extractivist logic by framing these processes in green terms. In doing so, it places Pakistan squarely within a global trend in which climate action is used to drive capital accumulation and elite control, instead of addressing ecological and social inequalities.

Introduction

It’s 11 July 2025 and Lahore is drenched in monsoon rains, with grey skies and flooded roads. An unusual sense of anticipation fills the city’s Press Club, where a press conference is about to begin on a new wave of state-led agrarian development projects called the Green Pakistan Initiative. Inside, journalists in damp shalwar qameez1 wait anxiously for the speakers to arrive. Among the speakers is a young bearded man in his mid-30s who is popularly known as ‘Zulfiqar Junior’. He is named after his grandfather, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s former socialist-oriented prime minister who was executed by the US-backed military dictatorship of Muhammed Zia-ul-Haq in 1979. Over the last year, Zulfiqar Junior, a young artist and eco-socialist, has emerged as the unlikely face of the peasants’ and farmers’ movement opposing the Green Pakistan Initiative. When he addresses the assembled journalists, he does so with a calm and composed demeanour, telling them: ‘We will not leave our farmers and peasants at the mercy of this madness’.

Beyond the Press Club, the political climate in Pakistan is currently marked by immense popular support for the jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan, who was ousted from the government three years ago in the country’s first successful parliamentary vote of no confidence.2 Since then, Khan has been imprisoned, convicted of corruption and leaking state secrets – charges many of his supporters describe as trumped up. Nevertheless, Khan has been able to mount a direct challenge to the authority of the country’s powerful military, which he believes was responsible for his ouster from the government.

In the period of political instability that followed Khan’s ouster, a coalition led by the centre-right Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz came to power. During this time the country also faced violent attacks by Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an armed group, as well as surging inflation, all of which fuelled public discontent.3 While the India–Pakistan war in May this year (2025) has helped the military to partially recover its public image, it has been unable to curtail the popularity of its most vociferous opponent, Imran Khan. Nevertheless, the country's generals retain massive political power within Pakistan, with many people suggesting the country has a hybrid form of governance whereby elected officials hold office but key decisions rest with the military.4

It was against this tense background, including growing economic woes and a crisis of balance of payments, that, in 2023, state authorities began the Green Pakistan Initiative, an ambitious programme of economic recovery that is the brainchild of Pakistan’s army and that is directly overseen by it.5 Through both domestic and foreign corporate investment, the Green Pakistan Initiative aims to bring modern agricultural practices to cultivable lands and to lands that are not currently cultivable. This is important because Pakistan relies heavily on its agricultural sector to sustain its economy (it contributed about 24% of GDP in fiscal year 2024-25). A central part of the Green Pakistan Initiative is the six canals project, which involves developing six major irrigation canals across arid regions in the country’s biggest province, Punjab, with the aim being to convert vast stretches of barren land into cultivable zones.

While officially framed as a productivity-enhancing effort, the Green Pakistan Initiative serves as the institutional framework under which large tracts of state land are being leased for corporate farming. Under this scheme, provincial governments identify so-called ‘barren’ or ‘unused’ lands and transfer them to a military-run company, Green Corporate Initiative Pvt. Ltd., established under the oversight of the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC). This company then enters into long-term lease agreements—typically for 20 to 30 years—with domestic and Gulf investors, who develop these lands for export-oriented agribusiness.

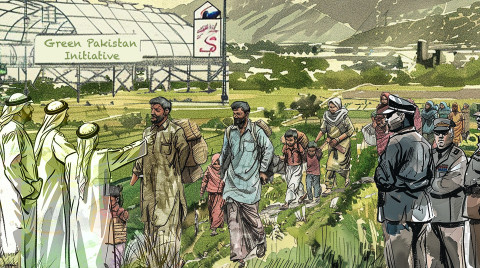

While the Green Pakistan Initiative is cloaked in the language of productivity and investment, the darker reality is now being highlighted by various movements across the country: of people being dispossessed from their lands and of those lands being appropriated by domestic and foreign capital, mainly from Gulf countries.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Roots of Elite Capture: A militarised developer state and class formations in Pakistan

Back in 1961, the first military dictator of Pakistan, General Ayub Khan, was welcomed with extraordinary pomp to the US after Pakistan joined the US-led Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and Central Treaty Organization (CENTO). These two Cold War military alliances were created to contain the spread of Communism in Asia and the Middle East; by joining them, Pakistan becoming a frontline state in the Cold War.6 It was for this reason that when General Ayub arrived at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington, he was welcomed with a full military honour guard and a 21-gun salute, and was personally received by US President John F Kennedy.

Aided by Western—and particularly US—support, General Ayub pumped billions of dollars into Pakistan’s agricultural sector, with many hailing a revolutionary transformation of the country’s agricultural landscape.7 Western outlets wrote reports on how Pakistan was on course to become a so-called ‘Asian Tiger’. Financial aid to Pakistan’s agriculture was part of an attempt to give legitimacy to the military dictatorship in Pakistan, while also quelling the possibility of a peasant insurgency of the kind that was common in much of the Global South during this period.8 Indeed, Nick Cullather has argued that US agricultural assistance to Asia during the Cold War was a form of green counter-revolution, stating: ‘The Green Revolution became the weapon of choice to ensure that the balance of power remained in America’s favor. Washington looked to agricultural technology to alleviate poverty and promote economic growth on a scale that would “discipline [Asia’s] unruly politics and shore up client regimes”.’9 Seen in this way, Washington’s technological monopoly was instrumentalised to ‘discipline’ politics, by binding peasants and farmers into an elaborate system of credit institutions and stripping them of land and agricultural autonomy. Under this new system, farmers had to take out loans, buy seeds, use chemical fertilisers and sell cash crops. They thereby became a part of a controlled economic circuit10 that restructured social relations and undermined possibilities for organising and revolt.11 This new system framed hunger as a technical challenge, one relating to a simple ‘lack of calories’, rather than being a political question that was directly tied to inequality and (land) dispossession.12

While the leftist regimes of Maoist China and post-revolutionary Vietnam carried out radical land reforms, such reforms were a ‘no-go’ area for the US-aligned regime of Ayub Khan. The regime instead pushed to increase agricultural productivity through the application of Western-backed technology and finance. Domestically, the underlying aim of these policies was to ensure Pakistan’s traditional large land owners stayed in control, preserving traditional class formations.13 On the international front, Pakistan’s role as a US client state was to present the US model as an alternative to Communism. Pakistan was not alone in this experience: this model of agricultural aid as a counter-insurgency strategy was forcefully implemented during the Cold War period in the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand.14

The US’s geopolitical backing of its client regime in Pakistan enabled the military dictatorship to establish an accumulative agricultural model in which the military plays a key role—a situation which continues till today. According to current estimates, approximately 12 million acres of land in Pakistan, or 4% of the total area, is under military control.15 This has led to the creation of a military landed class that extracts rents from tenants without actually living on the land. For example, in regions like Okara, Bahawalpur and Balochistan, lands that were historically cultivated by tenant farmers under colonial leases were reappropriated by the military in the early 2000s, with those who claimed ownership subjected to repression. Importantly, the lands allotted to the military-bureaucratic establishment are irrigated by water from government-run canals, while the canals used by small farmers are often dry, silted or broken, forcing them to rely on expensive tube wells, which raises the cost of production.16

While militaries in countries like Egypt and Turkey hold significant economic power, the scale of direct land control by the military in Pakistan is unusual: it has one of the most entrenched military landed classes in the world. Through its land holdings, preferential access to water, and state patronage (in the form of subsidies for agriculture), the landed military elite dominates the rural economy and earns rents and profits, but is distanced from actual farming. Tenants, on the other hand, are vulnerable to evictions, especially when the profit motive leads to the real estate-isation of agricultural land, mainly in relation to elite housing projects.

The transition from agricultural landlordism to urban real estate capitalism has further intensified the class divide between a military-connected landed elite and tenant farmers. This transition accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s as state-backed housing schemes expanded in major cities. In this shift, land was no longer tied to production but rather was increasingly subject to speculation and accumulation. Rural and peri-urban areas increasingly came into the ownership of the sprawling housing societies that were established to cater to the urban middle and upper classes. For example, 25% of land in Lahore, the capital of Pakistan’s biggest province, Punjab, falls under the Defence Housing Authority, a real estate and housing development authority originally established to provide housing to retired and serving military officers.17 Over time, the Defence Housing Authority has become one of the most powerful real estate empires in the country, catering to urban elites, both civilian and military.

Another example of these housing societies is Bahria Town, which is one of the largest private housing schemes in South Asia, with massive projects in Lahore and Karachi. Bahria Town exemplifies the model of turning land into fictitious capital and is a paradigmatic case of elite rentierism where wealth is not produced by labour or innovation but is instead extracted by owning and manipulating land markets. Bahria Town is also a notorious example of what David Harvey terms ‘accumulation by dispossession’, being known for its forced evictions of longstanding peri-urban communities. In cases where attempts at outright eviction fail, the conglomerate adopts an alternative strategy: it buys land at a cheap rate through exercising coercion over the owners, and then re-zones those lands from agricultural to commercial uses.18 Once reclassified, it aggressively markets the land, appealing to upper class aspirations of luxury and exclusivity. Even before the development of housing projects on the land begins, plots are presold to investors, generating massive capital upfront.19 This capital is then used to buy additional land, creating a cycle of speculative expansion. Land is thereby transformed from a productive asset into a tool for elite accumulation. Land remains central in this equation but its value now comes from its exchange potential, not its use value.

What is novel in this transition from agricultural landlordism to real estate capitalism is the entry of new elite groups into the control and management of lands, a position that was previously dominated by feudal families. Beginning in the 1980s and accelerating after the 2000s, this elite came to include military generals, judges, bureaucrats and real estate tycoons, who work in partnership with key state institutions. Thus, while real estate capitalism represents a new phase of capital accumulation, it also builds on the older feudal structures. Importantly, patterns of dispossession continue. It is also a case of elite capture, which takes the form of exploiting regulatory loopholes, influencing local development authorities, and creating a parallel economy based on expectations of land value appreciation. This is all a textbook example of what Marx referred to as fictitious capital.

The consequences of the transition from agricultural landlordism to real estate capitalism have been dire for Pakistan’s economy. As land has become the main site of capital accumulation, the economy has shifted from production to speculation, leading to the erosion of industrial competitiveness. Naked rentierism precludes industrialisation and the development of productive forces: instead, capital is misallocated to the real estate sector in pursuit of faster and safer returns. Between 2015 and 2020, real estate attracted more capital than the textile sector, which still accounts for roughly 8–9% of GDP and more than half of Pakistan’s exports.20 As a result, the country struggles with a persistent trade deficit, with external debt now exceeding $90 billion. Pakistan now relies mainly on foreign remittances to stay afloat.21

At the societal level, this real estate capitalism has led to the decay of rural tenancy systems and to increased food insecurity, which now affects 43% of Pakistan’s population according to World Food Programme estimates. With rural poverty still hovering above 35%, migration to cities and other countries from rural households has intensified, leaving agricultural workforces increasingly feminised.22 However, this feminisation is not accompanied by increased autonomy or institutional support for women, as women’s labour is either unpaid or poorly remunerated. In the province of Sindh alone, an estimated 60% of women work as unpaid labourers on family farms, while the annual value of their labour is estimated at $2.46 billion, constituting 57% of the total agricultural labour in the province.23

Concomitant with the precarity of labour in rural sites, the real estate-isation of land is accompanied by a housing crisis that is leading to dramatic spatial inequality in major urban centres, such as Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. According to a study by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, the country currently faces a total housing shortage of 10.3 million housing units. This backlog is unevenly distributed, with some provinces facing very high shortfalls, such as Punjab at nearly 40% and Sindh at over 57%.24

In this context, development for the few often means displacement for the many, with entire Katchi Abadis (informal settlements) sometimes razed to the ground, without any plans for the resettlement of their occupants. For example, in the heart of the country's capital, Islamabad, a violent operation was launched in July 2015 to demolish one Katchi Abadi for a real estate project, affecting almost 8,000 working class people, mainly belonging to the minority Christian community. Such demolitions are class-based attacks on poor residents that benefit real estate investors, in collusion with the military-controlled state. They constitute a symbolic and material criminalisation of homelessness and poverty, while the violations of the rich go unnoticed.25 Despite being justified in the name of the housing crisis, these real estate schemes are by design inaccessible to the urban working poor. Developers frequently invoke the rhetoric of providing housing, yet their projects cater to affluent sections of the middle and upper classes, not to low-income groups. As a result, the demand for genuinely affordable housing in urban Pakistan remains unaddressed.

The historical trajectory that has seen a shift from agricultural landlordism to real estate capitalism has now entered a new phase: that of green capitalism. This new phase of accumulation is cloaked in green rhetoric and sustainability jargon, yet it is being implemented by the same actors as are involved in real estate capitalism. It thus represents a shift in language but not in logic. This shift mirrors the global trend of green capitalism, in which climate action is designed to generate finance and extract rent, rather than to disrupt extractive logic or confront ecological and climate injustice. In green capitalism, the language of ‘climate-smart agriculture’ and so-called ‘new green revolution’ technologies is increasingly deployed in state and donor discourse. This framing does not merely highlight technical solutions, it also implicitly casts traditional land users as inefficient, positioning industrial agriculture as the inevitable future.26 As Tania Li (2007) argues, such discourses seek to transform complex agrarian questions into solely technical questions, turning struggles over land and livelihoods into narrow problems of productivity and efficiency.27 In practice, this legitimises corporate farming schemes, including the Green Pakistan Initiative, while obscuring the dispossession of peasants and the environmental knowledge embedded in local practices.28 Thus, in green capitalism, environmentalism has become a new frontier for elite capture that enables dispossession under the guise of ecological stewardship. The aim is less about restoring ecosystems and more about re-legitimising land grabs in the name of conservation, agricultural efficiency and carbon offsets.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Planting Profits: Unpacking the Green Pakistan Initiative

وارث شاہ نیویں نیویں وسدا، جتھے کھیتی روئے کھُرکاں مارے

‘Waris Shah walks with a bowed head through villages where crops cry under the weight of oppression’—Waris, in Heer.

Heer by Waris Shah is Punjab’s equivalent of the Iliad, Shahnameh, or Alf Laila Wa Laila. It is a book of love and land, filled with rural imagery, where characters break into monologues and dialogues, often with spiritual and social overtones. Heer is a masterpiece of Punjabi Sufi literature written in the 18th century that reflects the south Asian tradition of storytelling called Qissa. Sung and celebrated for centuries, Heer eerily reflects the patterns of agrarian distress we see in modern Punjab. In Waris Shah’s telling, the protagonist Ranjha’s lover Heer is not only a woman but also a symbol of Punjab’s land: fertile, proud and autonomous, yet subjected to domination. Her forced marriage to protect her clan’s honour shows how both women and land have long been traded and violated. This continuity matters: while in Waris Shah’s time such metaphors captured the workings of patriarchal and feudal authority, today similar dynamics unfold in new guises as agricultural land is converted into real estate without the consent of those who till it. This Qissa reminds us that development without consent is always a violation, no matter how it is packaged. Likewise, the protagonist Ranjha’s decision to become a Sufi wanderer after his brothers deny him his rightful share of land resonates with the plight of contemporary peasant migrants who leave their homes in order to find a means of survival in the face of agrarian hardships.

Shaped by the colonial legacy of land classification and canal colonies—settlements built by the British in Punjab near to irrigation canals that transformed arid land into farmland that was worked for revenue—the modern state governing Punjab today presents a different vision of the province to that portrayed in Heer: one that is devoid of the rich cultural tapestry of the past. This vision imagines the land through a language of development and security. The deep cultural memory embedded in its soil, richly articulated by poets like Waris Shah, is now being overwritten by technocratic and unjust visions of development. Land has been turned into a quantifiable asset and is no longer the home of the myriad communities that gave it life and meaning through their labour and culture. This is a moral and epistemological rupture from the past brought about by the colonial, post-colonial and neo-colonial logics of development, as imagined through projects like the Green Pakistan Initiative.

Launched officially in 2023, the Green Pakistan Initiative is pitched as a panacea that can solve the country’s economic problems and enhance national food production through mechanised agriculture. Its website states: ‘The Green Pakistan Initiative (GPI) is an agricultural project which is a joint effort between the Government of Pakistan and Pakistan army aimed at enhancing agricultural development in the country.’29 The initiative claims that it is improving agricultural productivity through applying modern technology and irrigation techniques, while creating large-scale employment in rural areas by attracting foreign direct investment, mainly from Gulf countries.

Beyond the stated objectives, the Green Pakistan Initiative must be understood as a broader institutional architecture that is being developed by the Pakistani government, in close cooperation with the military leadership, to consolidate control over land and agricultural investment in the country. This architecture includes the establishment of the Land Information Management System (LIMS), the Green Corporate Initiative Pvt. Ltd. (GCI), and the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), alongside the construction of six new canals in Punjab, all of which collectively centralises decision-making around land use, water allocation and agricultural governance under the military’s oversight.

The effects of this ambitious venture are already being felt across the country. According to estimates, approximately 1 million peasants and small-scale farmers are expected to be displaced and dispossessed due to corporate farming projects under the Green Pakistan Initiative.30 Moreover, serious questions have been raised over the process of land acquisition for these projects.

The initiative dates back to early January 2023 when, following the installation of a caretaker government in Punjab, the Pakistan military proposed to expand corporate farming projects in the province under what came to be called the Green Pakistan Initiative. Acting on this proposal, and despite the fact that it lacked a constitutional mandate to make such long-term policy decisions, the caretaker cabinet approved single-source leases31 of more than 45,000 acres of so-called state land in Bhakkar, Khushab and Khanewal districts32 to the Pakistan military’s Frontier Works Organization (FWO), an engineering and construction conglomerate, under a joint venture with the Punjab government focusing on agricultural and livestock development. These leases have a term of 20 years, but they can be extended for another 10 years. In June 2023, the Lahore High Court declared this entire process unconstitutional, ruling that the caretaker government had exceeded its authority and that the military had no constitutional role in commercial farming. However, that judgement was suspended on appeal in July 2023. This paved the way for the ongoing acquisition of so-called state lands for corporate farming projects under the Green Pakistan Initiative.33

It is important to note that land labelled as state-owned is in fact cultivated by tenant farmers under the tenancy system introduced by British colonial authorities over a century ago. However, these farmers’ ownership rights either remain unrecognised or are frequently contested by the state. Similarly, many areas classified as uncultivated are actually accessed seasonally by pastoralist and nomadic communities for grazing and subsistence.

The controversial leases for corporate farming under the Green Pakistan Initiative have paved the way for the eviction of tenant farmers across Punjab. One such case is Muhammad Nagar village, in Khanewal district, where, on 4 November 2024, the Assistant Commissioner suddenly ordered the eviction of tenant farmers from land they had lived on for 120 years.34 In response to the order, around 300 local farmers held demonstrations, chanting the slogan ‘Ownership or death!’ and declaring that they would never leave their land. After clashes, the administration retreated, but a sense of fear continues to hang over the area and the farmers continue to receive threats of forced eviction from the local administration.

To facilitate the expansion of the Green Pakistan Initiative, in July 2023 the government instituted two key mechanisms:

The Land Information Management System (LIMS): Established under the joint oversight of the federal government and the military, the LIMS is a key component of the Green Pakistan Initiative, It is a government agency tasked with identifying, mapping, and monitoring state-owned and uncultivated lands for corporate farming projects in the country. The LIMS has so far identified approximately 4.8 million acres of land for corporate farming projects in the initial phase of the initiative.35 The LIMS is a part of a broader government push to centralise land use decision-making and promote technological methods in agriculture to increase productivity and crop yields.36

- Green Corporate Initiative Pvt Ltd (GCI): The GCI is a company established by the Pakistan military under the Green Pakistan Initiative to manage and lease cultivable land transferred to the army’s control through joint venture agreements with provincial governments. While legal ownership of the land remains with the provinces, the GCI functions as an intermediary, leasing these lands to corporate and foreign investors for periods of up to 30 years to facilitate large-scale agribusiness projects.

Following these developments, the Green Pakistan Initiative was expanded to the province of Sindh. Although information on the activities of the Green Pakistan Initiative remains limited, appearing in only a few documents available to the public, it can be determined that around 52,000 acres of state land in the districts of Khairpur, Sukkur and Ghotki have already been leased by the Sindh government to the GCI.37

While the 52,000 acres leased in Sindh and 45,000 acres leased in Punjab may seem modest, these initial steps mark the first phase of a much larger plan to bring 4.8 million acres of so-called state lands and uncultivated land in Sindh and Punjab under similar lease arrangements. Importantly, this development represents a drastic change in how land is governed: tenant farmers who have inhabited and tilled state lands since colonial times will lose their right of ownership over their land; and the so-called uncultivated lands previously accessed by pastoral and peasant communities under customary use will be reclassified and leased for large-scale corporate farming projects. The initiative also reflects the military’s deepening role in the management of the agrarian political economy, with a shift towards a model that invokes the global language of sustainability while reproducing pre-existing structures of exclusion and dispossession.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Enter Gulf investment

Gulf participation in the Green Pakistan Initiative is already materialising, in the form of a series of investment deals involving countries like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia. These deals have been facilitated by the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), a body created in 2023 to fast-track foreign investment under the Green Pakistan Initiative. For example, in 2023 the UAE committed to over $35 billion in deals with Pakistan, including direct investments in corporate farming, halal meat production, and date palm production to be exported to UAE.38 Major UAE entities like Al Dahra, ADQ and AD Ports Group have signed memorandums of understanding with the Pakistani government on expanding their role in port, logistics, and customs infrastructure. These developments signal a deepening UAE presence in Pakistan’s agri-food and logistics sectors.39

Similarly, Saudi Arabia has positioned itself as another key player in the Green Pakistan Initiative’s agrarian agenda. In 2023, it pledged a projected $25 billion investment over two to five years, with agriculture as a central focus, and it made an initial $500 million investment in agricultural ventures facilitated through the new LIMS.40 Several Saudi companies, including Sarh Attaqnia Co., Al Marai, Saleh, and Al-Khorayef, have entered into partnerships with Pakistani conglomerates, such as the Fatima Group, for large-scale cultivation of rice, barley, oats, and silage under corporate agriculture farming schemes.41 The Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company (SALIC) has also been offered a project to establish a cattle farm in Punjab with 30,000 animals and an annual meat production capacity of 6,000 tons for export. The company has also showed an interest in leasing 49000 acres of land for corporate farming projects.42 Moreover, a March 2024 deal allotted 5,000 acres in Bhakkar (Punjab) to grow alfalfa that will be exported to feed Saudi dairy cattle.43 Saudi dairy conglomerate Al Marai was invited to join this venture despite its controversial operations in the United States, where it stands accused of diverting scarce Colorado River water to grow alfalfa in drought-stricken Arizona. Alfalfa is a water-intensive crop and growing it in a semi-arid region like Bhakkar will deplete already stressed groundwater.

These projects all reveal a deepening integration between Pakistan’s agricultural sector and the Gulf food security agenda. This must be understood within a broader political economy in which capital accumulation is framed as food security and modernisation. As Adam Hanieh has shown, such agricultural ventures are in fact less about ensuring food access for Gulf populations and more about reinforcing corporate power by spatially reorganising resource control and displacing environmental costs, particularly water depletion and pollution, onto host countries.44 In Pakistan, this logic materialises through the Green Pakistan Initiative, where Gulf investors collaborate with Pakistan’s military-led agribusinesses to convert state-claimed ‘fallow’ lands into export-oriented corporate farms. Yet such ‘fallow’ or ‘unused’ designations are rarely neutral. Lands officially classified as vacant or state-owned have often long been accessed by pastoralists, whose informal or customary rights are erased through bureaucratic reclassification. A study on the Cholistan Desert reveals that approximately half a million Rohi pastoralists depend on animal husbandry and seasonal grazing across desert ranges.45 Their livelihoods are now being threatened by the reappropriation of land for mega agricultural projects under the Green Pakistan Initiative. Residents across the region report that traditional grazing areas are being systematically taken over, leaving livestock farmers and local communities without viable alternatives.46

As Hanieh argues, these ventures form part of a transnational ecology of accumulation that binds Gulf and South Asian corporations together in a shared project of resource extraction and environmental risk displacement.47 They follow on from earlier failed attempts to cultivate the Gulf’s own deserts, which led to ecological degradation and massive financial losses. This prompted a strategic shift that Rafeef Ziadah (2019) terms the ‘externalization of food insecurity’, a process (elaborated by Christian Henderson (2020)), whereby Gulf agro-capital offshores environmental and food risks through transnational land acquisitions.48

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Hydrology of Dispossession: The six canals project

One key element of the Green Pakistan Initiative is the construction of six new canals in Punjab Province. Approved in July 2024, the 176 km canals are projected to irrigate approximately 1.2 million acres of arid land in the Cholistan Desert of Punjab Province, supported by both public and private investment.49 This mega project has already generated fierce resistance in the lower riparian communities of the country, particularly in Sindh Province.

While the project’s planners suggest that the new canals will draw water from the Sutlej River, in reality the river does not have enough water for this purpose. Water flow in the Sutlej River has become highly erratic due to Indian upstream dams and climate variability.50 According to the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty between Pakistan and India, the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej rivers are largely controlled by India. Data from the Indus River System Authority indicates a persistent decline in flows in these three rivers, while Punjab and Sindh are currently facing 20% and 14% water deficits, respectively.51 This means that water to the six new canals will very likely actually be diverted from the Indus River, which is controlled by Pakistan under the Indus Waters Treaty framework. Such a move would reduce Sindh’s share of water, in violation of the 1991 water apportionment accord governing inter-provincial water sharing in Pakistan.52 This would cause serious environmental damage. In particular, it would lead to further destruction of arid-zone mangrove forests in the Indus Delta in Sindh, which require a delicate balance of fresh water and seawater. Reducing river flow to these zones will increase salinity, destroying mangrove habitats and threatening the livelihoods of around 100,000 farmers who engage in traditional fisheries in this zone.53 This would also undermine the natural defences against cyclones and tsunamis, as mangroves act as climate buffers for coastal communities. Moreover, the canals project also threatens to turn around 4 million acres of agricultural land in Sindh into barren land, due to resulting water shortages.54

The current uneven balance of power over water access, between Punjab and Sindh, has its origins in British colonial rule. In the colonial era, Punjab, was the location of a large canal colonisation project: an extensive irrigation network that was constructed across the Indus Basin with the aim of both supporting agriculture and asserting strategic control over the area. Through this project, the British developed what historians call a military-agriculture nexus in the region. Punjabi soldiers returning from British imperial wars abroad were rewarded with lands in the newly created ‘canal colonies’, as the British sought to create a loyal landed peasantry who would act as the backbone of the colonial order in the Indian subcontinent.55 The legacy of the British canal colonisation project was that Punjab’s dominance in water access was baked into the post-colonial state of Pakistan. Historian Daanish Mustafa points to this hydraulic infrastructure as a site of domination whereby regions outside of Punjab are treated as colonies within the larger nation state. Mustafa argues that the Indus Basin irrigation system was designed to enable extractive agrarian capitalism that benefits large landowners and military-bureaucratic elites. Thus, water is diverted upstream to benefit central regions, at the expense of downstream users.56 In effect, Sindhi grievances over water are not about scarcity: they are about historical dispossession perpetuated by the post-colonial state.

The six canals project being implemented under the umbrella of the Green Pakistan Initiative essentially reproduces the logic of the canal colonies, but cloaked in the language of green development. During colonial times, canal colonies were designed to expand cash crop cultivation and generate maximum land revenue for colonial administration. Similarly, by diverting water to zones that will host large-scale corporate farming projects backed by foreign and local capital, the six canals project attempts to align water infrastructure with the corporate interests of local and foreign investors, leaving downstream communities in Sindh to bear the ecological costs.

The six canals project was launched without any environmental assessment or debate in the national parliament, and the state did not consult the affected parties. Neither was Sindh’s consent sought through the Council of Common Interest, a constitutional body responsible for resolving disputes and coordinating policies between the federal government and provinces, particularly in relation major inter-provincial projects. As indicated above, Punjab, as the upper riparian province, has historically exercised disproportionate control over irrigation and land access, to the detriment of downstream Sindh. As Ayesha Siddiqi (2023) argues, state spatial practices and water governance have institutionalised Sindh’s marginalisation within Pakistan’s political economy, shaping enduring perceptions of economic exploitation and political exclusion.57 In addition to the historical dispossession resulting from hydraulic infrastructure, Sindh’s objection to the six canals project stems from the lived realities of its deltaic communities. Many in southern Sindh depend on riverine and deltaic ecologies for their livelihoods. Fishing in rivers and estuaries, often carried out at a small scale and managed by local communities, is a main source of income for these households.58 The diversion of Indus water undermines these livelihoods, pushing deltaic communities to migrate or to seek wage labour in bigger cities. This further reinforces the political alienation Sindhis have long experienced. As a result, many Sindhis blame the Pakistani federation for their dispossession.

The most striking paradox of the six canals project is that the state is attempting to convert the arid Cholistan Desert into cultivable land through constructing the new canals, even as it risks rendering vast tracts of currently fertile agricultural land elsewhere barren. A more rational approach than expanding cultivation into ecologically fragile zones would be to put an end to the ongoing conversion of agrarian land into residential housing schemes.

Another initiative that embodies this paradox, and which further exposes the detrimental ethos of state development initiatives, involves the Ravi Riverfront Urban Development project, also known as the RUDA project, which was initiated by the Government of Punjab in 2020. Officially presented as an environmental restoration and urban renewal plan to ‘revive the Ravi River’, the project involves large-scale land acquisition across more than 10,000 acres of fertile agricultural zones on Lahore’s periphery. Under the guise of river rehabilitation, the RUDA project envisions a series of real estate developments that will convert fertile agricultural land along the banks of the Ravi River into extensive housing schemes.59 Thus, while the government claims to be ‘greening’ deserts such as Cholistan by expanding irrigation networks, it is simultaneously dismantling Punjab’s most productive agrarian landscapes through their conversion into urban property.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The SIFC

At the heart of the Green Pakistan Initiative is the SIFC. As indicated above, this powerful body serves as the fundamental conduit for fast-tracking projects under the initiative. Its purported claim is to grant fast-track approvals for agricultural projects under the initiative and to coordinate between federal and provincial authorities to remove bureaucratic red tape and regulatory hurdles for investors who are interested in Green Pakistan Initiative-related projects. Its leadership includes senior army officers, with the Prime Minister and the Chief of the Army Staff being its main decision makers. According to its official website, the SIFC aims to attract investments from friendly countries in selected sectors such as agriculture, renewable energy and mining, improve the ease of doing business in Pakistan, and promote coordination across government institutions, with the Pakistan Army playing a facilitative role.60

The SIFC is a sophisticated continuation of the praetorianism that Pakistan has faced since its inception, whereby the military takes key national decisions. Even the mainstream political parties in the country see the SIFC as an instrument for rolling back the legislative and financial autonomies that were granted to provinces under the 18th amendment to the country's constitution, which was passed in 2010.61 The amendment was a significant democratic reform that reversed many authoritarian features of the constitution introduced under preceding military dictatorships. It strengthened provincial autonomy and gave a semblance of parliamentary supremacy to national decision-making. It was a democratic counterweight to decades of military rule and centralisation at the federal level.62 The military is uneasy with the amendment because it has eroded centralised control by devolving administrative power to the federating units. It also reduces central influence over resource allocation as it gives provinces greater financial autonomy, thereby shrinking the federal government’s fiscal space. Critics argue that the SIFC is an attempt to achieve backdoor recentralisation of constitutional authority, and that it undermines the spirit of the 18th amendment, as the body lacks constitutional legitimacy and sidesteps democratic processes. Its decisions are not debated in the parliament, and they are not subject to provincial scrutiny. The SIFC seeks to centralise investment decisions related to agriculture, energy, industrialisation and even tourism, which are constitutionally the mandate of provinces under the 18th amendment.

Unlike the overt military takeovers of the past, today’s military overreach is disguised in the language of investment and reform. The underlying aim, however, remains the same: to expand the army's institutional footprint. General Ayub’s modernisation in the 1960s enriched the landed aristocracy, while General Musharraf’s privatisation drive in the 2000s favoured real estate moguls. Each time, the reforms were initiated by invoking narratives of development and the national interest. The SIFC uses the same playbook: faced with an economic crisis of its own making, the ruling elite now justifies sweeping changes in governance by appealing to ‘efficiency’ over legality, and ‘development’ over justice. At its core it is an attempt to rewire the economy in favour of entrenched elites, rather than a response to economic collapse.

This rewiring is not new: it draws upon the legacy of centralised control instituted by the British colonial administrative system. The post-colonial state inherited the hardware the British had installed to facilitate imperial plunder—what historian Hamza Alavi has described as an overdeveloped state.63 During the colonial era, strong military and bureaucratic institutions, modelled on British institutions and imbued with an ethos of hierarchical discipline were tasked with maintaining order and facilitating extraction. In the Indian subcontinent, these mechanisms extended beyond the military and bureaucracy to include comprehensive legal and property regimes designed to secure imperial control. Within this system, the law was primarily a tool for resource expropriation, rather than a vehicle for ensuring justice. Laws like the Punjab Land Alienation Act of 1900 enabled easier taxation, ensuring land remained in the hands of agriculturist castes deemed loyal to the British crown.64 Similarly, mobile pastoralist lifestyles were criminalised under the Criminal Tribes Act and various Forest Acts, which redefined shared landscapes as state property, thereby restricting indigenous access to them. These legal instruments have remained largely intact in the post-colonial period, enabling elite control over land and resources.65 The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 is a case in point. Initially introduced by the British to consolidate land on which railways and imperial infrastructure were built, it remains in force today with minimal revision. Its ambiguous clause relating to acquiring land for the ‘public good’ is relied upon to expropriate land for real estate ventures and military-run development schemes.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The SIFC’s Renewable Energy Gambit

While the SIFC primarily directs and approves large-scale agricultural investments under the Green Pakistan Initiative, its mandate is now expanding to encompass other strategic sectors, such as renewable energy. One of its stated priorities is attracting foreign and domestic investment in the country's renewable energy sector, which it claims stands at 3,300 gigawatts (GW).66 This pivot to renewables is framed within the broader green and sustainability promise. SIFC’s stated ambition is to add 60 GW of renewable energy to the country’s grid by attracting domestic and foreign investment by 2034. According to its own projections, if achieved, this would reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), oil and coal, which are currently mainly sourced from Gulf countries, thereby saving critical foreign exchange. It would also help to reduce the need for ‘load shedding’ (temporary outages), while contributing to climate mitigation efforts under Pakistan’s Nationally Determined Contributions.67

But the SIFC’s ambitious plan to boost renewable energy is in apparent contradiction to the government’s recent policy initiatives in the energy sector, including an effort to stall the growth of decentralised solar rooftop systems, which are increasingly being installed by citizens. Reuters68 and the Financial Times69 have reported that Pakistan’s rooftop solar boom is a rare instance of a bottom-up innovation in an otherwise dysfunctional energy regime. As at early 2025, more than 125,000 consumers had registered net-metered solar connections, with a cumulative capacity exceeding 1,200 MW. This is equivalent to approximately 2.5% of Pakistan’s total installed capacity. While still modest in scale relative to the national grid, rooftop solar is the fastest-growing segment of the renewable energy market. The surge in solar has created a burden of around $570–720 million on non-solar users annually, as solar households are credited for the power they send to the grid at the same rate they pay for electricity, even though they do not share in the fixed costs of maintaining the system.70 This has increased tariffs for consumers who rely on the national grid, pushing Pakistan’s power sector towards what analysts call a ‘death spiral’, where rising tariffs drive more people to adopt solar, further shrinking the paying customer base.71 In March 2025, the government responded to this problem by slashing the net-metering rate from Pakistani rupees (PKR) 27/unit ($0.10) to PKR 10/unit ($0.037), significantly reducing the financial returns for solar rooftop users. As a result, the average payback period—that is, the time required for households to recover the upfront cost of installing solar systems through savings on electricity bills—has increased from about two years to between two and five years.72

This policy reflects conflicting tendencies within the government: on the one hand it seeks to attract large-scale foreign investments in renewable energy under the Green Pakistan Initiative; on the other, it is disincentivising a citizen-led solar transition. These contradictions point to a broader preference for capital-intensive projects and a model of renewable energy generation that is profitable for investors, rather than one that prioritises equitable access or meeting people’s energy needs. Without aligning its macro-level planning with the realities of bottom-up innovation, the country’s renewable energy ambitions risk becoming extractive—not merely through resource capture, but through what Shalini Randeria calls the ‘cunning’ recombination of state and market authority that sidelines local claims to commons. In this sense, the ‘cunning state’ operates by invoking the language of sustainability to extend control over resources, allowing market forces and bureaucratic institutions to reinforce one another in ways that deepen existing hierarchies—an arrangement that ultimately consolidates state power rather than democratising governance.73

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Fightback Against the Green Pakistan Initiative

In Sindh, the opposition to the six canals and to corporate farming is led by various political parties, including Awami Tehreek (AT) and Jeay Sindh Mahaz (JSM), as well as Zulfiqar Junior’s Bhullan Bachao Tehreek, which works to protect Indus River dolphins. Together with other social and political movements from across the country, these organisations form a cross-provincial resistance that is grounded in shared experiences of dispossession. It is this dispossession that Zulfiqar Junior emphasises when he describes the six canals project as one that will benefit private capital, rather than landless farmers in Cholistan and Sindh.74

Resistance to the six canals project resonates particularly strongly in Sindh, attracting writers, poets and other members of the intelligentsia, who have collectively condemned the canalisation of land.75 Experts on the issue are challenging the feasibility as well as the legal status of the project.76 The issue is a rallying point for disparate groups in the province who see it as yet another betrayal by the ruling Pakistan People’s Party. Although the Party has come out in opposition to the project, critics point to the Party’s inability to defend provincial interests because of the military’s involvement, and they argue that the Party is complicit in the broader pattern of ‘developmental militarism’ that is consolidating state control over land and resources. The result is a widening trust deficit between the Party and its traditional support base in rural Sindh, where the canalisation of land and the expansion of corporate agriculture are read as forms of internal colonisation.77

Public conferences, marches and protests have therefore become the norm in the province, with resolutions calling for distributing land among peasants and abolishing the SIFC.78 Nationalist parties such as the Qaumi Awami Tehreek (QAT) and Jeay Sindh Mahaz (JSM) have condemned the Green Pakistan Initiative more broadly as an existential threat to the province’s agriculture and livelihoods, while warning of the broader political and social instability it may unleash. For many in Sindh, the struggle against these projects represents both a defence of the Indus River as a lifeline and a rejection of corporate and federal encroachment in provincial affairs.

In Punjab, resistance against corporate farming and the Green Pakistan Initiative is spearheaded by Anjuman-e-Mazareen Punjab (AMP) and Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee (PKRC).79 These movements have a rich history of grassroots mobilisation to correct historical injustices. AMP is at the forefront of what is widely known as the Okara Military Farms Movement, a nonviolent struggle for peasant rights in Punjab centring on the question of the ownership of lands in Okara that were allocated to local families by the British colonial administration more than 120 years ago but which are now controlled by the military. The British colonial state set up these farms as part of its canal colonisation scheme (referred to earlier) to serve military supply chains: they settled tenants on the land to cultivate it on the condition that they would pay a fixed rent. AMP’s president Meher Ghulam Abbas explains: ‘When Pakistan was created, these lands should have automatically been given to us. Instead, this state put different departments in charge of our lands, asking us to sharecrop.’ The current dispute began in early 2000 when the Pakistani Army attempted to convert the status of the tenants to that of contract farmers, meaning the military would legally own the land and farmers would work on it as wage labourers. The tenants, under the leadership of AMP, refused this, claiming that they were the rightful owners of the land.The tenants resisted eviction and launched a nonviolent mass movement demanding recognition of their land rights. In response, AMP leaders were arrested under anti-terrorism laws, accused of being Indian-backed agents.

Since 2000, AMP has mobilised hundreds of thousands of farmers around their central demand for ownership of the lands in Okara.80 Meher Ghulam Abbas asserts: ‘We have one slogan: it’s “ownership of our land or death.”’ His words are anchored in a deep sense of generational belonging: ‘My grandfather's grave is here, so is my father’s and so will mine. My sons are the fourth generation tilling this land and we are not giving an inch of it to any corporation’.81

At a press conference in Lahore earlier this year, various movements, political parties and progressive farmer associations, including AMP, came together vowing to resist corporate farming and the Green Pakistan Initiative specifically. The press conference was called after police tried to evict tenants from a farm in Hasilpur, in Bahawalpur district of Punjab. Since then, opposition to corporate farming has evolved from localised tenancy disputes to a national agrarian movement that has the backing of political parties and civil society.

Alongside AMP, another key actor in this struggle is PKRC, which is an extensive network of more than 20 peasant and farmer organisations from across three provinces. PKRC was formed to coordinate groups in the early 2000s that were involved in the Okara military farms issue. Its General Secretary Farooq Tariq asserts: ‘[The] Green Pakistan Initiative has brought us all together, that’s why we were able to mobilise in more than 30 towns and cities across Pakistan opposing corporate farming and [the] six canals project, and we are being heard and taken seriously.’82 As these words suggest, Tariq believes that the Green Pakistan Initiative and corporate farming have brought leftists, progressives and nationalists together around one common agenda: ‘Water was always a nationalist issue in Sindh, but you see, even the movements and farmer groups in Punjab opposed the construction of six canals and stood with their Sindhi brothers and sisters. This sent a very good message and formed a unified front against corporate capture.’83 Tariq explained that a day of action had been called by PKRC in collaboration with AMP on 14 April 2025.

The convergence of the struggle across provincial lines marks a shift in the country’s political landscape. In previous disputes over water and land, provincial divisions were deepened. For instance, the proposed Kalabagh Dam on the Indus River at Kalabagh in Mianwali District, Punjab, was a defining inter-provincial controversy during the Musharraf regime (2001–2008). The dam, which has never been constructed, drew widespread opposition from the provinces of Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and from civil society groups more broadly, who saw it as a mechanism that would further ensure Punjab’s control of water. The issue divided not just provincial governments but also civil society and progressive groups, essentially pitting people in Pakistan’s different provinces against each other. By contrast, the opposition to the Green Pakistan Initiative and to the six canals project has increased solidarity among farmers’ movements. Farooq Tariq asserts: ‘it was historic that opposition to the six canals is spearheaded by groups in Punjab which was later taken up in the Sindh Province. This was always our aim: to unite movements and fight together.’ 84

The present resistance to corporate farming, the Green Pakistan Initiative and the six canals has thus united various progressive forces in the country. In addition to those already mentioned, these include left-wing parties, such as the Haqooq-e-Khalq Party (People’s Rights Party) and the Pakistan Mazdoor Kissan Party (PMKP), alongside urban actors like journalists and student organisations. One of the defining traits of this coalition is that it redefines the language of development to centre the rights of farmers and peasants. It presents an alternative vision to state-led positivist visions of development. This broad coalition has the potential to reshape the balance of power between the state and rural communities. However, it also faces risks. In the past, anti-terror legislation has repeatedly been used to criminalise peaceful mobilisation, and its continued presence poses a serious threat to the movement resisting corporate farming and the Green Pakistan Initiative. Police and military backing for corporate farms further heightens the risk of intimidation and eviction. Moreover, while this movement demonstrates growing strength, its potential for achieving long-term structural change remains uncertain.

The ongoing developments relating to corporate farming, the Green Pakistan Initiative and the six canals project raise critical questions about the shift from a military-industrial complex to a military-agro-industrial complex that is emerging in Pakistan. The drive for capital accumulation through green agricultural programmes raises the need for careful reflection on how the language of sustainability is employed by state authorities to dispossess communities and, in some cases, create further environmental harm. It also highlights the growing involvement of transnational actors in these initiatives. Finally, it calls for greater consideration of how Pakistan, despite not being a major contributor to global climate change, has overseen a ‘developmental regime’ that often exacerbates the local and regional effects of climate change.