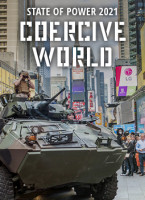

Expression meets repression Social movements and police violence in Chile

Topics

Chile's national police, the Carabineros, have a long and bloody track record of silencing groups demanding their labour, social and economic rights. Their continued existence and violence shows how the Carabineros serve as a key institution for maintaining social structures that perpetuate social injustices that benefit the elite.

Crédito Caiozzama

October 2019 marked a watershed in Chile. The social uprising was the eruption of silenced and ignored demands, grievances and aspirations that had been building up for decades. In the words of one of the main slogans: ‘It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years’. The slogan represented the anger at an economic development model instituted by the Pinochet dictatorship – and followed afterwards – that has led to more precarious living conditions and generated one of the most unequal societies in Latin America.

The authorities did not see it coming or know how to deal with it. Just days earlier, President Sebastián Piñera told a national television show that ‘in the midst of the turbulence in Latin America, Chile is a genuine oasis with a stable democracy’. He praised the country’s economic growth and stability compared to other countries in Latin America, with crises affecting Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Haiti. His blindness to the uprising reveals the existence of two visions of Chile: one shaped by the elite, who do not acknowledge the structural violence implicit in state policies, and the other shared by those who suffer it.

The same blindness affected the manager of the Santiago subway system, who said on television, ‘kids, this didn’t catch on’ two days before the protests sparked by the increased subway fare shook the city and the entire nation. The ‘cabros’, literally ‘kids’ referred to the thousands of students who had begun jumping subway turnstiles on 14 October 2019 in protest. His words were like a match dropped into an oil tank, as people of all ages took to the streets of cities throughout Chile to express their various social demands. In Santiago, as a result of the massive fair evasions, the subway administration decided to close its stations on 18 October, leaving thousands without transport and forcing them to walk for miles back home. Protests escalated with at least 20 stations burned. Meanwhile, a photo of President Sebastián Piñera eating pizza at one of the richest neighbourhoods in Santiago went viral. From then on, a series of protests shook the country.

On 19 October, the government declared a constitutional state of emergency, which restricted freedom of movement and assembly. It sent the military out onto the streets and imposed a seven-day curfew, but this did not stop the protests. On the contrary, despite violent repression, huge demonstrations continued to be held daily. Carabineros, the Chilean national police force, used tear gas, water cannons filled with chemicals causing burns, and rifles loaded with heavy metal pellets against children, teenagers, protestors, artists and journalists. Many were arbitrarily detained. A Carabinero even entered, shot at and wounded adolescents at school. The authorities and the Carabineros intimidated Chilean artists who joined the public demonstrations.

Every day there were so many injuries that health professionals set up volunteer stations near the protestors’ meeting places to offer them assistance. But even the Red Cross health posts were attacked by the Carabineros. At that time, the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet begun so there was no objective or reasonable justification to prohibit mass gatherings.

By reason or by force: the state’s brutal response to Chile’s awakening

The October 2019 social uprising has been compared to the August 1949 ‘Chaucha revolution’ in Santiago. Both were characterised by a precarious economic situation, social discontent caused by the government’s failure to meet social demands and a hike in public transport fares, as well as the subsequent protests and severe repression that left several dead and injured. While there are clear similarities, the two historical moments also differ due to the government responses.

In 2019, force rather than reason prevailed, whereas in the Chaucha revolution, the government of Gabriel González Videla was forced to reverse its decision, change the cabinet and undertake extensive economic and political reforms. Videla even lowered the transport fare and created a reduced tariff for students. The Sebastián Piñera administration, by contrast, opted to ignore the underlying causes of the conflict. It strengthened and supported the repression carried out by the Carabineros and invoked the internal state security act, thus criminalising the social movement.

As a result, the excessive use of force by the Carabineros and army violence in the name of order and security has become a regular occurrence. Reports published by international organisations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights condemned the excessive state violence – and the resulting serious human rights violations.

Chilean institutions also documented the violence. The Public Prosecutor’s Office reports that 33 people were assassinated while exercising their right to protest yet only four of these incidents were attributed to agents of the state. The National Human Rights Institute reports that between 17 October 2019 and 13 March 2020, 460 people suffered eye injuries and 2,133 were wounded by firearms. Between 18 October 2019 and 31 March 2020 the Attorney General’s Office received 8,827 reports of crimes committed by agents of the state, 6,626 by Carabineros. The reports include cases of torture, sexual violence and homicide. The Carabineros themselves revealed that in the first two weeks of the social upheaval alone, they fired 104,000 rifle shots which apparently left 126 people with eye injuries.

Repression: Structural violence enforced by the Carabineros

Créditos Luis Bahamondes (https://www.instagram.com/p/CMccJdZFSgS/)

There is a pattern to the Carabineros’ actions : they repress and censor all dissident voices, be they protestors, artists, adolescents or journalists, basically all speech that displeases them or criticises the status quo. This is sufficient reason for action, with violence as their institutional response. They regularly violate national and international laws without state sanction, despite inflicting violence and injuries. Indeed, the political authorities have continued to support them and their violence with impunity, even though they have injured thousands and killed others.

Take the case of Moisés Órdenes, for example, a 55-year-old man who was protesting in a public square and holding a frying pan when 12 Carabineros attacked him. The result? A punctured lung, a dislocated shoulder and blinded in one eye. Fabiola Campillai, a 36-year-old woman was completely blinded when a tear gas canister hit her in the head while she was going to work a few blocks from her home. Gustavo Gatica, a 21-year-old student and photographer, was also completely blinded when Carabineros shot him in both eyes during the social uprising.

They act very differently with government supporters out on the streets: protecting and even escorting right-leaning people protesting against social movements. On 5 September 2020 in Santiago, Carabineros repressed a protest of health workers who were demanding the regularisation of their employment status, while over 200 pro-Pinochet supporters of ‘el Rechazo’ in a protest held at the same time in Las Condes were allowed and even protected by the Carabineros.

Historical roots of military policing

This pattern of protecting the elite is not new, and is deeply rooted in the history of the institution. The Carabineros were set up by the Ministry of War in 1907, and were made up of soldiers and emerged from a unit of ‘Gendarmes’ whose principal role was to protect internal colonial settlements. While in 1925, they theoretically became independent of the army, they remained a highly militarised, hierarchical institution, led exclusively by army generals.

The Carabineros have a long and bloody track record of silencing groups demanding their labour, social and economic rights. For example, the 1931 ‘riot of Norte Grande’ led by leftist groups in response to the national economic crisis, ended in the arrest, murder and disappearance of around 100 people, including labour and communist leaders. Similarly, in 1934 in the Ranquil Massacre, this time in southern Chile, Carabineros killed more than 100 peasants and settlers who were contesting the confiscation of their land. In 1946, the Carabineros were involved in the ‘Massacre of Bulnes Square’ in which six people were killed. One of them was 19-year-old Ramona Parra, known as the first martyr of the Communist Youth in Chile. She was assassinated for marching in solidarity with the unions of the Mapocho and Humberstone saltpetre works. Then, in the late 1960s, in the ‘Pampa Irigoin Massacre’ Carabineros took the lives of nine men and a nine-month-old boy, who was asphyxiated by the tear gas, and another 52 people suffered gunshot wounds.

Most of these cases never saw justice, despite the gravity of the crimes.

Despite these incidents, since the 1960s, the Carabineros has received proportionally more funding than the army, and has been in direct proportion to their increased use of force against civilians. In response, the government of Salvador Allende disbanded the Carabineros’ most violent group, but after the 1973 coup d’état, the Pinochet military government reconstituted it as a ‘Special Forces’ unit. After 1973, the Carabineros became Pinochet’s machine of massive repression, its officers actively participating in systematic human rights violations in Chile throughout the civil-military dictatorship. At the end of the dictatorship in the 1990s, several groups condemned their complicity with the civil-military dictatorship, but the forces were not disbanded and remain active today. The Chilean constitution currently recognises the Carabineros as an armed corps accountable to the Ministry of the Interior and Public Security.

Their reputation has received a battering in the wake of several incidents in the past few years. In 2017, the so-called ‘Operation Hurricane’ case exposed the planting of incriminating evidence to frame eight members of Mapuche communities., In 2018, the murder of a member of the Mapuche community, Camilo Catrillanca, became the focus of solidarity from across Chilean society and generated harsh public criticism of the Carabineros’ actions. Although the official statements initially referred to an alleged ‘confrontation’, testimonies and images of the events clearly contradicted these. Sergeant Carlos Alarcón was handed an 11-year custodial sentence for the murder of Camilo Catrillanca and a further five years for the attempted murder of the minor who was with him.

So, how does an institution with a track record like the Carabineros de Chile still exist today? There is no one explanation, but clearly the Carabineros serve as a key institution for maintaining social structures that perpetuate social injustices that benefit the elite. Similarly, by allowing the Carabineros to continue to inflict life-changing injuries and murder civilians with impunity, the state has sided with violence. The psychologist Tamara Jorquera explains that the abuses serve as a form of social control and a way to subdue the population for fear of falling victim to their violence and impunity. The social order is preserved by creating subjects who are afraid to protest.

However, Jorquera also argues that despite this, there are always expressions of resistance. Art and creativity in particular have emerged as one of the main means to express collective demands without people exposing themselves to the abuses and excesses of the Carabineros.

Expression as a political tool in Chile

In the first few days of the social uprising, it was clear that the mainstream media was not up to the task and on several occasions, its coverage was biased and even censored. It did not report on social demands; it showed images of some protestors engaging in riots and violence, but not the excessive use of violence by Carabineros and the military. Thanks to the widespread use of mobile phones to record videos and images capturing both the social demands and the violent repression of protestors, social media became the main channel of information from many different perspectives from those witnessing the events in Chile.

To offer a more balanced view, the CIMA art gallery began broadcasting events directly from the so-called ‘Zona Cero’ or ‘Ground Zero’ of the social uprising, to provide real-time coverage of events in the vicinity of Plaza Dignidad (Dignity Square). Thanks to this work, they were recognised as one of the main media documenting the social and political events since the beginning of the social unrest.

Beyond broadcasting and digital media, others took their messages directly to the streets with countless artistic expressions. Walls and monuments became the canvases to depict social demands, making visble the reasons for the social unrest. Visual artists such as Caiozzama, Fab Ciraolo, Juana Pérez, Paloma Rodríguez, Danny Reveco, la Colectiva Pésimo Servicio, Delight Lab and others used their creativity to convey social, economic and environmental demands through their art. Songs such as ‘Cacerolazo’ by Ana Tijoux, ‘Paco Vampiro’ by Alex Anwandter, ‘Cueca del Despertar’ by Andrea Andreu, ‘Somos la resistencia’ by Natisú, ‘Desperté’ by Tata Barahona and many others became the soundtrack for the protests against the violence inflicted by the Carabineros as well as the many acts of solidarity within the social movements.

These artistic expressions had such an impact that the authorities began to harass and intimidate a number of artists. Mon Laferte, a world-renowned Chilean artist, for example faced charges for her televised comments that ‘there are many cases where the police and the military were the ones who started the fires’.

Similarly, Las Tesis, the collective that created the viral hit ‘Un violador en tu camino’ (‘A rapist in your way’) recognised by Time magazine, faced a criminal suit by the Carabineros for ‘inciting violence against authority’ for their video ‘Manifiesto Contra la Violencia Policial’ (Manifesto against Police Violence). In the video, they recited:

‘They persecute us, block the exits of our homes, provoke us, infiltrate as protestors and set everything on fire. They parade through our streets while armed. They throw tear gas, hit, torture, rape, destroy and blind us…. The government does not listen and renews their weaponry. And they don’t stop. The police don’t look after me, my friends look after me. .. Burn the cops, burn the cops

Such censorship has gone unpunished, as have the intimidations.

The state’s attempts to maintain its coercive power and social control border on the absurd. Mayor Felipe Guevara of Santiago, spent more than 250 million pesos (close to 285,000 euros) on a ‘whitewashing’ process in mid-February 2020, literally. The mayor ordered workers to use white paint to paint over more than four months of artwork decorating the façades of the Centre Gabriela Mistral (GAM), the municipal theatre, the Alameda Art Centre and other buildings near Ground Zero.

The social and political situation in Chile today is a result of the many social demands that were ignored and silenced during decades of authoritarian rule, which itself was designed to maintain an economic model which left many Chileans in precarious living conditions. People have long used non-institutional means to express their social demands, but in Chile the excesses and abuses by the police – in particular the Carabineros – were used as a key mechanism to restrict peoples' capacity to protest. The police in Chile were constantly mobilised against citizens who sought to assert their economic, social, cultural, environmental and indigenous rights. Indeed, the institution of the Carabineros seemed to be designed to have minimal control and accountability in order to generate a widespread fear of falling victim to its violence and impunity, and through that fear uphold a dominant social order.

Despite this, the social uprising since October 2019 succeeded in giving voice to social demands thanks to the many independent media, journalists, photo-journalists, citizen reporters sharing their work in social networks. These voices also publicised the abuses and violence of the Carabineros and military ignored by traditional media outlets. At the same time, the artistic expression seen on the streets, walls, and monuments echoed with the social demands, the struggles for the rights of the most marginalised, and the commemorations of the many victims of state violence.

Art has proved such a powerful means to express social demands and condemn state violence that the Carabineros have tried to harrass and intimidate artists who have shared ideas that have unsettled the authorities. Despite many attempts to stop artistic expression, artists continue to expose their abuse, showing that critical art is a political tool and a form of resistance to the social and political models that dominate most of Latin America.

Créditos Caiozzama