A New International Economic Order from Below

Regions

Step into the autumn of 1973, where the Transnational Institute (TNI) emerged in Amsterdam, a beacon of hope against authoritarian regimes and corporate giants. Founded by visionaries like Richard Barnet and Marc Raskin, TNI embarked on a quest for a new societal ethos, challenging the status quo through groundbreaking research.

The North-South Dialogue and the Beginning of the TNI

During its early years, TNI operated as a network of fellows. This was more in line with Barnet’s idea of the institute as a ‘communication system’ than the office with an in-house team it is today. Raskin’s original conception of TNI was for it to be a decentralised network that would facilitate the realisation of projects put forward independently by its fellows.

Soon, however, following the establishment of the TNI Planning Board by the institute’s first director Eqbal Ahmad, projects became more centrally driven. The board would coordinate which proposals could go forward, who would get what amount of funding, and so forth. The institute had two primary centres, in Amsterdam and Washington D.C., where the TNI leadership would meet and organize public events. Nevertheless, fellows remained spread out across many countries.

Aside from its organisational function, TNI offered its fellows material assistance and international contacts, the latter mainly by means of public events.2 In Amsterdam, this was famously done with the ‘Lessons of Chile’ conference held in late February, 1974. There, exiled former Allende officials met alongside European Socialist Party representatives, academics, and think tank executives.3 The conference attracted much ado in the press, putting TNI on the map as an important hub for radical thought amongst European leftists. Such a hub felt more prescient than ever as the radical spirit of the late ‘60s appeared wilting in the aftermath of the Chilean coup.

Still, hinting at the possibility of radical global change, meetings were beginning to occur at international forums around the same time.

Lasting from 1974 till 1981, these meetings made up the North-South Dialogue, a series of diplomatic summits in which actors from countries of the Global North and South debated the future of global trade and development. One important set of proposals that came out of these meetings was the New International Economic Order (NIEO). This proposal was aimed at instituting natural resource sovereignty, transnational corporate regulation, preferential and non-reciprocal trade agreements for developing countries, and technology transfers.

The ideas underlying the NIEO stemmed from dependency theory, an analytical framework which contends that the global trade order structurally causes the extraction of surplus capital from the Global South to the Global North, thereby preventing the former from being able to technologically innovate which ultimately perpetuates global inequality. Along with Brazilian economist Celso Furtado, the Argentine economist Raul Prebisch developed and propagated this theory via his role as the Executive Director of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL)between 1950-63 and as the founding Secretary General of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)between 1964-69.

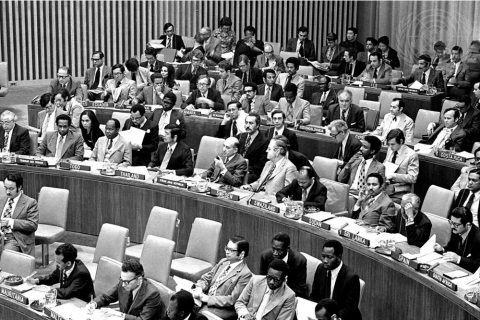

In 1964, inspired by Prebisch’s ideas and spurred on by stagnant economic growth in the developing world, representatives of the non-aligned Global South at UNCTAD formed the Group of 77 (G77), a coalition to end economic dependency. Over the course of the next decade, the G77 developed a set of policies at UNCTAD I, II, and III. Emboldened by the success of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, the G77 finally put forward its proposals by passing two resolutions at the UN General Assembly in 1974: The Declaration for the Establishment of a NIEO and The Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States.

This initiated almost a decade of international negotiations over how to reform global trade and development policy which collectively came to be known as the North-South Dialogue.4

Developing an Approach to Global Economic Reform

Spearheaded by its Amsterdam office, TNI began to promote the aims of the NIEO through anti-report initiatives. TNI’s role in regulating transnational corporations began in early 1974 when Eqbal Ahmad struck a partnership with Counter Information Services (CIS), a London-based research collective. CIS was the first to produce what it called ‘anti-reports’ on British companies. These were pamphlets which contrasted the immense wealth of the companies under review with the massive costs on people and the environment that the generation of this wealth produced. Since the members of thecollective were protecting their privacy, it was up to TNI to conduct press conferences on behalf of the CIS after the publication of every new anti-report.

In the autumn of 1974, TNI collaborated with the CIS and another investigative organisation, the Amsterdam-based Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), to produce an anti-report on Courtaulds, one of the ten biggest firms in the UK at that time. The report caused an uproar in the British press, leading Labour MPs to call for an investigation of the firm from the House of Commons.5

In November 1974, TNI brought the concept of the anti-report to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO)World Food Conference to discredit the Western-backed development model that was being propagated there. Critical of the agrobusiness-dominated FAO, the TNI report World Hunger: Causes and Remedies argued that the Western agricultural practices that were being pushed by the FAO onto developing countries was increasing their dependence on the Global North. In typical TNI fashion, the institute’s current president Susan George, who was still a fellow at the time, organised a press conference at the FAO event itself and presented the report to a crowd of 400 attendees. This included the then-president of the G77, who personally encouraged the institute to intensify its focus on the NIEO.6

This intensification commenced under Eqbal Ahmad, who put together TNI’s first Fellows’ Meeting in March, 1975. There, the fellows outlined four possible main projects, one of which was to meet the challenge of the NIEO. Effortsslowly started to take shape, and priority was given at this stage to building a network. Part of the endeavour included the Club of Rome of Reviewing the International Order (RIO) project,7 an initiative designed and coordinated by the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen to produce and internationally promote comprehensive practicable proposals for an NIEO, including ‘a global planning system’ run by the UN’s economic agencies which were to be converted into global ministries.8

Despite these initial steps, it truly began to manifest as a project under the TNI’s new leader Orlando Letelier, a former Allende government minister. Letelier initially developed a relationship with TNI during his tenure as Chile’s ambassador to the US. After the 1973 coup, Letelier became one of several Allende cabinet members to be imprisoned by the Pinochet junta. However, under international pressure organised by the Venezuelan government, Letelier was released from prison on the condition that he would live in exile. Soon thereafter, IPS fellow Saul Landau contacted the former minister to ask him if he wanted to join the IPS as a fellow himself. Letelier accepted the offer and moved to Washington in 1975, where he quickly rose through the ranks of the institution. By March, 1976, Letelier was appointed as TNI’s general director.

The International Economic Order Project

In his position as TNI’s general director, Letelier reoriented the institute’s agenda more strongly towards the NIEO. Together with Richard Barnet, Michael Moffitt, and TNI Amsterdam fellow Paresh Chattopadhyay, Letelier developed a new programme, the ‘International Economic Order’ (IEO) project, in which TNI was to take on a central role in facilitating the North-South Dialogue. It was to do this by building a network of like-minded think tanks, international organisations, civil society groups, and national political parties around itself from which it could cultivate and propagate its ideas. This included UN bodies such as the aforementioned CEPAL and UNCTAD, but also the Non-Aligned Movement.

In addition, the IEO programme was to continue the work that had previously been done on multinational corporate monitoring, noting that the structuring of the global economy was not merely the remit of the state but also that of the corporation.9 At the heart of this vision was a commitment to dependency theory and a fierce opposition to the theory of comparative advantage promoted by Keynesian liberals as it related to agricultural production for developing countries, as well as to the free market dogma of the early neoliberals in the Gerald Ford administration.10 In the IEO’s first pamphlet, Moffitt and Letelier set the tone by declaring that it was not enough to simply resolve inequality between nations, but that a new international economic order was necessary to resolve the inequality within nations as well.11

Tragically, however, Letelier’s tenure would end almost as soon as it began. The Chilean secret police assassinated him in September, 1976, also killing Ronni Moffitt, a fellow IPS economist and Michael Moffitt’s wife, in the process.

Letelier’s vision lived on under his successor Howard Wachtel, who was asked by Richard Barnet to take the reigns of the IEO programme.12 A leading economist in the revival of radical political economy within American academia, Wachtel continued the critique of the liberal Keynesian developmental state from a leftist perspective, arguing in his first IEO draft discussion paper that the welfare state had created “a political vacuum in which progressive programs are...non-existent.”13 The IEO plainly needed to transcend the liberal order.

Letelier’s networking initiatives also persisted. By early 1977, for example, TNI had gained official consultative status in the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and had established contacts within other targeted UN bodies, as well as with numerous other nongovernmental organizations.14 In addition, as the co-founder of the Union of Radical Political Economists, an academic association of radical leftist economists, Wachtel also brought his own vast network to the IEO programme. This included his contacts at the influential Institute for Development Studies’ (IDS) Dependency Working Group at the University of Sussex,15 as well as ties to renowned dependency theorists such as the Brazilian economist Celso Furtado.16

The IEO team spent the late 1970s building up a repertoire of pamphlets, and eventually books, and promoting them to governmental, intergovernmental, and nongovernmental institutions. The first of these included Michael Moffitt and Orlando Letelier’s pamphlet The International Economic Order and Howard Wachtel’s The New Gnomes, which were both published in June, 1977. The former was the IEO’s first splash into print, sold as a warning to US President Jimmy Carter’s administration that more cartels would form if it continued the trajectory set by its predecessor. The latter was a groundbreaking study on the private lending spree by multinational banks in the developing world, accelerated by the Carter administration and which facilitated austerity and authoritarianism in the Global South.17

Following the success of these works, the IEO team planned ‘a series of international meetings of parliamentarians, church leaders, union leaders and academics from the US, Canada, and Europe’ to spread their ideas.18

The International Campaign

Concerning such legislators, Wachtel himself already had prior relationships with the legislative and executive branches of the US. He had previously delivered seminars on the NIEO to the State Department and served as a consultant to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress. The US participants in the IEO programme thus became involved with the staff of Congressman Michael Harrington, chairman of the House Subcommittee on Economic Development, to advise on development policy, as well as with the staff of Senator Frank Church, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy, on multinational banking regulation.19

During one episode, TNI fellows in Washington attempted to end IMF austerity programs by working with Congressman Tom Harkin and Senator James Abourezk. The aim was to pass amendments to the bill that sanctioned US participation in the so-called Witteveen Facility, a capital infusion to the IMF worth $1.7 billion. The goal was to put a condition in place that the organization end its austerity mandates. However, despite Wachtel’s regular meetings with staff of the Treasury department, their initiative received tremendous pushback. The Treasury organized enough opposition to sink Abourezk’s amendment, and whittle down that of Harkin, to only call for the IMF to study the effects of its conditionality policy.20

Outside of the halls of Congress, the IEO group promoted their agenda internationally as well. Wachtel conferenced vociferously for this purpose. He participated in a French Socialist Party conference on autogestion, the workers self-management movement of the French Left during this period.21 The New Left economist also helped organize the 1978 First International Conference on Economics of Workers’ Management in Yugoslavia which featured labour economists from across the West.22 Wachtel also continued to meet regularly with representatives from governmental and intergovernmental organizations, including at the World Bank, from where he had somewhat covertly retrieved his New Gnomes dataset in the first place.

Michael Moffitt, for his part, also promoted the IEO programme, attending a month-long conference hosted by the University of Sussex in November 1977.23 Additionally, on the basis of her book How the Other Half Dies and a subsequent IEO project on world hunger, Susan George featured in the IEO’s global campaign, notably attending the UN Conference on Science and Technology for Development and the FAO’s World Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development in 1979 to promote her technological dependency thesis.24

TNI’s activism resulted in real action taking place within intergovernmental institutions. Although they could ultimately not affect change in the short-term, these acts began to cement TNI’s position on the world stage. One instance of concrete action that occurred as a result of IEO campaigning was the Swedish Confederation of Professional Employees (TCO) using The New Gnomes to pursue multinational finance regulation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As part of its Trade Union Advisory Committee, they submitted a proposal to the OECD Committee on International Investments and Multinational Enterprises that the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises needed to include regulations on multinational banking.25

Elsewhere, the IEO campaign had also helped the IPS build up the connections with NGOs necessary for the organization of the NIEO conferences in Jamaica and Tanzania in October, 1979 and June, 1980, respectively. These conferences were planned in collaboration with the governments of Michael Manley and Julius Nyerere to gather experts together who would breathe new life into the North-South Dialogue by conducting original research on what the NIEO could look like going forward, and how to achieve it. Their conclusions were summed up by the Terra Nova Declaration and the Arusha Initiative, respectively, and later distributed to delegates at the Seventh Special Session of the UN General Assembly.

Their hopes were quickly dashed the following year, however, as the North-South Dialogue was ended outside the UN system at the 1981 North-South Summit in Cancún. There, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher made it clear to the representatives of NIEO’s proponents that in their view, free markets, not regulated trade, was to stir economic development. Its participants were consequently unable to reach any substantial agreements. With the onset of the Third World Debt crisis, the Global South was suddenly left at the mercy of newly elected neoliberal governments in the Global North who now demanded neoliberal reform.

The Pivot to Global Labour

Around the same time, at TNI’s Amsterdam office, a more permanent initiative was taking shape. Under the local leadership of former CIS director Basker Vashee, TNI began contemplating the potential of mass outreach through the circulation of its anti-reports to civil society organisations in the Global South. After all, their report on Unilever had been read by people from Nigeria to Singapore. Even a Zulu translation had featured in an underground newspaper for South African workers.

In 1978, thirty groups, including TNI, CIS, and SOMO, gathered together to establish the Transnational Information Exchange (TIE) with funding from the World Council of Churches. Based out of TNI Amsterdam, participants planned to research and distribute information to workers around the world.26 Back in Washington, support for a similar initiative began growing after Wachtel and Moffitt received a letter from Eqbal Ahmad, informing them that Algerian and Cuban representatives had approached him after a Non-Aligned Movement meeting about TNI supporting their newly-proposed Information Centre on Transnational Corporation.27

That same year, the IEO group sent a proposal to the TNI Planning Board for a Multinational Monitoring Project. In this project, the IEO group planned to work with organisations beyond just the CIS, such as the Pacific Asia Resource Center in Japan, to publish pamphlets and books on whole industries.28

Although at first this project did not get far off the ground, by January, 1983, TNI Washington revamped the initiative under the new name of the Transnational Corporations project and it was to work in cooperation with the TIE. Under Jorge Sol, John Cavanagh, and Deborah Smith, this project produced numerous texts during the 1980s, including a study on MNCs and the global alcohol market with the World Health Organization and another study on MNCs and beverages more generally with UNCTAD.29 The Transnational Corporations project also featured conferences in Amsterdam and Washington to organize civil society against MNCs.30 This allowed the IEO to prepare US House representative Don Pease for his legislative actions on labour standards,31 including his involvement in the banning of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation from insuring MNCs that did not enforce worker rights abroad.32 Though the IEO was ended by the late 1980s, this focus on multinationals has persisted on both sides of the Atlantic till this day with the TIE still serving the labour movement globally.

Moreover, despite the IEO programme persisting well into the 1980s, its initiatives had less and less to do with the NIEO. While Jorge Sol still travelled to related events such as the Socialist International’s 1983 conference in Jamaica on the aftermath of the Cancún meeting, the team was under ‘no illusions’ about the future success of the NIEO.33 By 1985, the IEO concluded that they needed ‘a new alternative economic posture’ in their present and future activities report. Aside from the new attention devoted to MNCs, the IEO founded the Debt Crisis Network to work on the escalating Third World Debt Crisis instead of the North-South Dialogue.

Working with the World Council of Churches, TNI began pursuing this issue by again following its strategy of researching, organising, and mobilising. In shifting its attention to this crisis, the IEO programme surmised that it could focus on fostering opposition to multinational banks by informing the public that any risk faced by these banks’ overexposure to debt in the Global South would be externalized through higher interest rates to their customers in the Global North. They would thereby link the issues of the working classes across the North-South divide.34 Thus, the spirit of the NIEO lived on and evolved within TNI despite the original project itself being moribund.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the failure of the NIEO and the onset of the neoliberal revolution, TNI carved out its identity internationally in this formative period. The Chile conference, the Kingston conference, and the Arusha conference had garnered a lot of attention in the media. The New Gnomes had been a big hit amongst readers of international political economy. TNI had managed to establish itself in all corners of the international community.

Furthermore, although TNI would continue to cultivate its influence in the higher echelons of power, TNI also took a decisive step during the days of the IEO programme by embracing a mass-based approach to its activism. Instead of remaining in the conference halls of the North-South Dialogue, TNI attempted to foster a North-South Dialogue from below amongst workers, activists, and academics – a dialogue which aided in keeping the spirit of the NIEO alive and a practice that TNI continues to apply to this day.