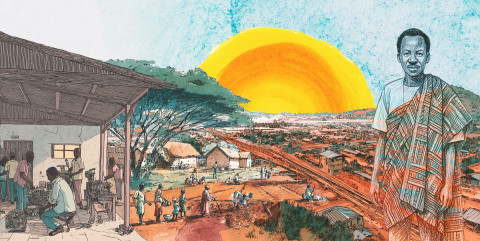

From Palestine to Africa, struggles for liberation expose the limits of colonial “development.” Revisiting Julius Nyerere’s vision, this article explores how Global South solidarity, industrial policy and self-determination offer urgent lessons for confronting imperialism today.

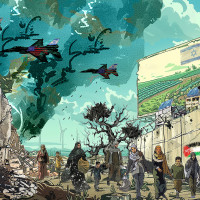

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Nyerere: the big picture

“Growing up in Tanganyika — later Tanzania — in the sixties was a unique experience in this part of Africa where many of our neighbours were going through turmoil, rocked by tribal conflicts and other forms of strife during the very same time when we were enjoying relative peace and stability in my country.” - Godfrey Mwakikagile1, Life Under Nyerere (2006)

Tanzania’s enduring political stability and unifying national narrative are manifestations of the statesmanship of Julius Kambarage Nyerere. They are extensions of a political project that he initiated before assuming the presidency of the country. His political trajectory began in 1954 with the founding of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), an organization which was dedicated from its inception to the ideals of national self-governance. In pursuit of this goal, Nyerere masterfully wielded the tools of the colonial order against that same order when he presented Tanganyika’s case before the UN Trusteeship Council in March 1955, and then again in November 1956. There he compellingly argued that the British administration was failing its mandate to prepare the country for self-rule. This successfully applied international pressure on the coloniser (Msekwa, 2005).

The attempt by the British colonial government to limit Nyerere’s political ambitions came as it forced him to choose between his teaching career (from which he inherited his title ‘Mwalimu’) and political activism. Nyerere was given an ultimatum by the leadership of St. Francis College, near Dar es Salaam, where he was a teacher. Nyerere was given a choice: stop his political involvement or lose his teaching job (Shivji et al., 2020). The move backfired as Nyerere’s conscious decision to relinquish his secure profession became a powerful public demonstration of commitment, transforming him into a full-time mobiliser. This allowed Nyerere to embark on a nationwide campaign articulating a vision of freedom and independence across Tanganyika culminating in TANU’s overwhelming electoral victory in the 1958-59 elections. This mandate positioned Nyerere to negotiate a transition to independence by 1961. He became the first prime minister, and later president, of an independent Tanganyika.

This same strategic wisdom guided his handling of the post-independence period and the formation of a unified Tanzania in 1964. As the principal architect of the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar — the two constituent parts of modern Tanzania — Nyerere proactively constructed a cohesive national narrative, upon which a common identity for Tanzanians stands. This was achieved through a number of sociopolitical tools, including the promotion of Kiswahili as a national language (Saul, 2012). The Tanzanian model of civilian and non-violent governance forged by Nyerere has proven remarkably resilient for decades. It stands in stark contrast to the coups, counter-coups and civil wars that plagued other post-colonial African states (Shivji, 2012). In any post-colonial society, long-term political stability is no historical accident, but rather an outcome of careful leadership and visionary political projects.

Nyerere’s project transcended political cohesion to deliver profound material services and expand the social wage for the Tanzanian populace. Upon independence, he became the president of a profoundly underdeveloped nation possessing no more than 12 fully qualified doctors at a staggering ratio of one physician for every 870,000 citizens (Nyangoro, 2002). By the end of his presidency, in 1985, this landscape was transformed. All urban centres and a third of villages had established medical dispensaries. More than 60% of the country’s 8,000 villages had access to clean water, and the state provided free health care and education, even covering student transport to schools (Townsend, 1998). Though Tanzania’s economic policies under Nyerere meant neighbouring states like Kenya often registered higher export revenues, Tanzanian’s developmental path yielded a more robust foundation of public welfare for its people, defining a different, socially-oriented metric of progress (Adésínà, 2009; Rodney, 1972; Townsend, 1998).

Just as significant as his domestic achievements, Nyerere’s international legacy stands as a formidable pillar of his political biography. He was distinguishable not only as one of the most original political philosophers of African independence, forging a project that is consciously tailored to the continent’s historical realities and needs, but also a prominent moral and strategic voice on the global stage. Under Nyerere’s leadership, Tanzania became the primary sanctuary and logistics hub of southern Africa’s liberation movements. Organisations like the ANC (African National Congress) and the PAC (Pan-Africanist Congress) of South Africa, FRELIMO (Mozambican Liberation Front), ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union) and ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People's Union), and SWAPO (South West Africa People's Organisation) of Namibia, all maintained headquarters in Dar es Salaam. This cemented Tanzanian’s status as an epicentre of regional anti-colonial struggle. In Tanzania, anti-imperialist solidarity also manifested itself in hosting one of the earliest Palestinian embassies in Africa, opened in 1973 (at the time it was an embassy/office of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO)) (Magama, 2020), staying consistent with the early Pan-Africanist stance of solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. The global anti-imperialist stance of Tanzania also manifested in various forms of solidarity with Vietnam, Cuba and China since the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, at governmental levels and at levels of student activism in the country (Burton, 2024).

In these ways, Nyerere emerged as an intellectual anchor of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), articulating a vision of non-alignment that is not based on passive neutrality, but active principled commitment to self-determination, anti-imperialism and a radical restructuring of an unjust global economic order. His distinguished stature was acknowledged globally when he was chosen to chair the South Commission in 1987. This assembly of intellectuals and statesmen from across the Global South was a direct response to a global order rigged against their states and nations. Nyerere’s leadership of this initiative confirmed his role as a foundational thinker for Global South solidarity, self-determination and development. More recently, in the year 2009, the UN General Assembly posthumously awarded Nyerere the title of ‘world hero of social justice’ noting that he ‘helped lead all of Africa out of colonialism, and into a social and economic system that placed human beings rather than maximisation of profit at the center of all economic endeavour’ (Brockmann, 2009: 7).

While Nyerere’s international, regional and national legacy is vast, this article focuses on the insights embedded in Nyerere’s industrial and developmental thinking. The subsequent analysis interrogates the economic dimensions of his Ujamaa philosophy, his regional approach to industrialisation, and the critical nexus of sovereignty, development and import substitution in his policy frameworks. Following this excavation, the article critically examines the reasons behind the marginalisation of Nyerere’s intellectual legacy in contemporary developmental discourse, before concluding with an exploration of how his recovered insights can inform and advance urgent debates in industrial policy in the contemporary Global South.

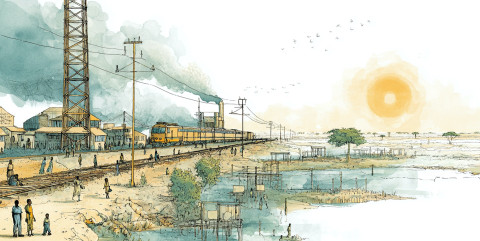

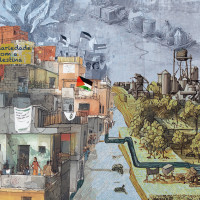

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Agrarian Foundation: Ujamaa as a pathway to industrialisation

“To us in Africa, land was always recognized as belonging to the community. Each individual within our society had a right to the use of land, because otherwise he could not earn his living and one cannot have the right to life without also having the right to some means of maintaining life.”

Ujamaa – The Basis of African Socialism, by Julius K. Nyerere,

published as TANU pamphlet in 1962

Ujamaa, a Kiswahili term denoting communality and familyhood, became synonyms for Nyerere’s sociopolitical philosophy and his distinct articulation of African socialism. This was not a mere ideological stance, but a comprehensive political project aimed at building national self-reliance. Its mechanisms were based on state leadership and technical support for rural cooperatives and the formation of self-managed agricultural communities, all oriented towards transforming agricultural production (Sheikheldin, 2015). At its core, Ujamaa sought to harmonise the twin objectives of equity and productivity, pioneering concepts of appropriate technology and participatory development that remain subject of global academic interests today (Morehouse, 1979; Sheikheldin, 2018). One of the major attractions of Nyerere’s legacy is that it was one of the few incidents in history where such concepts were implemented statewide, thereby revealing their real-world potential, challenges and policy requirements.

Nyerere’s vision for a socialist organisation of labour in Africa, and more specifically Tanzania, was predicated on two foundational principles. First, the objective centrality of the rural economy, which engaged the vast majority of the population and generated most of the revenue for the state. Second, a profound valuation of historical African ways of social organising, particularly the extended family unit and its tradition of communal ownership. This was coupled with an explicit rejection of a universal one-size-fits-all socialist model. Nyerere argued consistently that the historical trajectory of Europe, catalysed by its industrial revolution, was fundamentally different from that of Africa. Therefore, Africa’s path to socialism could not be a mere imitation of foreign blueprints (Nyerere, 1977c). He was quoted as saying, ‘If Marx had been born in Sumbawanga [a locality in Tanzania], he would have come up with the Arusha Declaration instead of Das Kapital’ (Shivji, 2012: 108).

Building on this foundation, Nyerere theorised that Tanzania’s route to equity and socialism must be an agrarian one, built on the continent’s primary assets: land, labour, and pre-existing communal values. He justified this approach on both pragmatic and sovereign grounds. Firstly, Tanzania lacked the necessary immense capital and specialised expertise to launch its development with large scale heavy industry. He also contended that relying on external sources for these resources would inevitably compromise the nation’s hard-won political sovereignty and create new forms of dependency. Secondly, and within the options for organising agriculture itself, the high cost of modern agricultural tools made individual ownership unattainable for the vast majority of people. Therefore, achieving efficient production that puts all the country’s resources to work necessitated communal ownership of these means of production, regulated and supported by a state that represents its citizenry through action and not just rhetoric.

These arguments were repeated in Nyerere’s speeches to the public throughout the 1960s. They were richly illustrated with references to African transition and the importance of political and developmental projects that suit the African context. And it was these arguments that formed the ideological bedrock for the Ujamaa villagisation project. Ujamaa villages were conceived as integrated residential and agricultural production units, farmed collectively utilising state services, with tasks and profits distributed via democratic and cooperative methods. The creation of these villages followed the nationalisation of colonially alienated lands and the creation of state-derived leasehold land-tenure systems on the remaining estates (Patnaik et al., 2011). In its initial phase from 1968 to 1973, the project was met with significant popular enthusiasm. Agricultural revenue to the state surged in the first year, outperforming the unreliable and often diminished inflows of foreign grants (Ibhawoh & Dibua, 2003). However, this momentum proved difficult to sustain. There was a slowdown in voluntary participation, largely attributed to the lack of direct financial incentives for individual farmers. This led to a policy shift. By 1973, Nyerere reversed course from voluntary and incentivized villagisation he emphasized previouslyand made it compulsory for all rural populations to live in villages.

The imperative to boost productivity within the Ujamaa framework took Nyerere’s policies beyond agriculture. He highlighted that rural women worked the longest hours, while other segments of the population maintained work schedules that were inadequate for the nation’s developmental urgency (Nyerere, 1977a). He also advocated for a radical rethinking of education, urging that curricula and structures — including age of enrollment — be redesigned to produce individuals equipped to serve and sustain their communities, rather than offering advancement to a privileged few (Nyerere, 1977d).

Crucially, Ujamaa’s agrarian focus was in no way an outright rejection of industrialisation, but a proposal for a complementary-phase model. The philosophy framed the anticipated increase in agricultural productivity as an essential prerequisite for creating the surplus capital needed to fund industrial expansion. Meanwhile, the model explicitly incorporated co-operatively managed, small-scale industries for processing agricultural produce. These small industries were envisioned and designed not as massive factories, but as decentralised cottage industries that leveraged local labour and raw materials without demanding prohibitive capital investment. As for larger strategic industrial facilities intended to serve the national market, like the Chinese-supported Friendship Textile Mill, Nyerere prioritised logistical efficiency, locating them in urban centers where existing infrastructure minimised additional costs (Nyerere, 1977b). Thus, Ujamaa envisioned a dialectical progression where the transformed agrarian sector would lay the material and social foundation for a uniquely Tanzanian decentralised path to industrial development. A major shortcoming of the model was that it overlooked class struggle within Tanzanian society, thus allowing wealthier peasants to use villages to further their own interests (Shivji, 1970).

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Industrial Policy of Self-reliance: freedom and development

“We are fairly comfortable now; foreign exchange is not one of our present problems. But we have to see that it does not become a problem, and we can do this by increasing and diversifying our exports, and by the deliberate development of import substitution industries”.

A speech by Julius K. Nyerere upon laying the foundation stone of the Bank of Tanzania building – Dar es Salaam, 9 December 1966

Like every facet of his political project, Nyerere’s industrial policy was fundamentally geared towards the overarching objectives of achieving self-reliance for Tanzania and securing freedom and development for its people. The intrinsic link between freedom and development is one of Nyerere’s major intellectual contributions. He articulated this at a time when mainstream discourse treated them as separate concerns. In his philosophy, freedom — including national sovereignty, freedom from hunger and poverty and individual freedoms — was contingent upon a material and intellectual foundation. It depended on increasing the wealth and knowledge available to the community; in other words, upon development. Conversely, he argued that true development can only be achieved when directed by free people and sovereign states capable of pursuing their own interests free from external subordination (Nyerere, 1973). This dialectical framework shaped his industrial strategy, as evident in his rationale for import substitution industries, which he justified as essential for liberating the nation from the vulnerabilities and dependencies resulting from the chronic need for foreign exchange.

To a great extent, the Arusha Declaration of 1967 was the foundational blueprint of this agenda. The TANU document penned by Nyerere explicitly links the ownership of the means of production to the goals of self-reliance and national industrial needs. The declaration mandates state ownership over a relatively large range of strategic assets including 'land forests, minerals, water, oil and electricity, news media, communications, banks; insurance; import and export trade; wholesale trade; iron and steel, machine-tools, arms, motor-cars, cement, fertilizers, and textile industries; and any big factory on which a large section of the people depend for their living, or which provides essential components of other industries; large plantations, and especially those which provide raw materials essential to important industries.’ In a catalysing article published about a month after the publication of the Arusha Declaration (Nyerere, 1968a), Nyerere elaborated that certain sectors were to be exclusively state owned. He described these sectors as major means of production and exchange, and they included minerals, electricity, communication, fertilisers and sectors that provide raw material required for essential industries. He also added the arms industry, mentioning that no private investors should have a share in tools of death. While other sectors could include private investors, the state must retain control over majority shares. These principles were rapidly operationalised via an extensive program of nationalisation and state-led investment. The policy was further radicalised in the 1968 pamphlet Socialism and Rural Development (Nyerere, 1977c), which proposed that public shares in joint enterprises should — whenever possible — be owned by worker cooperatives, further deepening the model of citizen ownership. In the same article, Nyerere also emphasised the importance of utilising the profits of publicly owned companies (or, as they are called today, state-owned enterprises (SOEs)) in national development and welfare.

This framework gave rise to a number of SOEs designed to command the heights of the economy, including the Tanzania Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) and the flagship National Development Corporation, a holding company of state ventures in cement, textile, beer and other consumer goods. Nyerere complimented this ownership structure with progressive labour policies, which included a national minimum wage. His approach to market regulation was also relatively pragmatic. In a presidential address in 1967 he debated the complexities of price control, arguing that unified national prices are only feasible if the state was to subsidise transportation to equalise base cost for sellers (Nyerere, 1977a). He used this example to caution against dogmatic, hastily-implemented controls that ignored regional economic disparities across the country. His solution for mitigating the complexities of price control was the creation of a national council for the matter.

In 1970, Nyerere issued a presidential circular decreeing ‘workers participation’ in public corporations. This established workers’ councils composed of representatives of workers and top management working as an advisory body to corporate boards. The initiative was designed to reduce industrial conflict, address workers’ alienation and enhance productivity by fostering collective ownership. However, the following period from 1971 to 1976 witnessed a surge in industrial disputes and strikes. Researchers attribute this to the policy of retaining pre-nationalisation management personnel and entering into management agreements with the same multinational corporations whose assets were nationalised (Shivji et al., 2020). This generated a stark and unregulated class conflict between workers, on one hand, and management and foreign capital on the other. The blind spot to class struggle appeared with its negative implications within the realm of industry as it did with agriculture.

Nyerere’s prioritisation of sectors that facilitated self-reliance, via the substitution of simple imports and the processing of agricultural produce, did not preclude ambitious efforts to pursue new technology. But the application of technology was deliberately strategic. For example, Nyerere clearly emphasised that the immediate goal was not to adopt the world’s most advanced machinery, but to utilise technology appropriately and within the skill level of the domestic labour force, thereby avoiding new dependencies on foreign expertise (Nyerere, 1977b). On the other hand, Tanzania also invested in strategic, ambitious projects to push the evolution of its national technological capabilities. One quintessential example was the local reverse engineering of automotive engines. Led by the Tanzanian research and technology organisations (referred to as RTOs; also called R&D parastatals) including the Tanzania Automotive Technology Centre (TATC) and the Tanzania Engineering and Manufacturing Design Organization (TEMDO), a strategic, publicly-funded project successfully reverse-engineered a complex internal combustion engine.2 The project, which began while Nyerere was still in power and was completed in the early 1990s after he was no longer in power, demonstrated high local capacity for advanced manufacturing and trained a generation of Tanzanian engineers and technicians. Ultimately, the engine prototype was not commercialised as a result of the subsequent political retreat and structural adjustment pressure after the Nyerere era (1961-1985). Still, the project stands as a powerful testament to the technical and institutional infrastructure forged under Nyerere’s industrial, economic and educational policies. This shows that while Nyerere’s industrial policy is not without flaws and room for improvement, it nevertheless leaves a legacy with significant successes worthy of learning from. This is the case particularly for nations of the Global South that are currently facing the resonant challenges and that share aspirations for self-reliance, freedom and development.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Regional Integration as Collective Self-Reliance

“We cannot have fifty iron and steel complexes in Africa at the present time. All of them would run at a heavy loss which we cannot afford…. We need to coordinate our industrial strategies, to exchange technical information, and to work out some means of concentrating those industries.”

Julius K. Nyerere, addressing the Organisation of African Unity – 28 April 1980

In articulations of his philosophy of self-reliance, Nyerere consistently clarified that it was not a prescription for isolation, but a prerequisite of a more equitable form of international cooperation. His vision presented self-reliance as an essential foundation for collective sovereignty, where nations freed from dependency could engage as genuine partners. His famous analogy about steel manufacturing powerfully illustrated this principle. Here, Nyerere argues that a single capital-poor nation could never afford its own steel mill, a cornerstone of modern development and industry. However, by sharing investments and pooling resources among neighbouring countries, such a project becomes economically viable. This model does not only minimise individual costs but also guarantees large integrated markets for the factory’s output, thereby transforming an impossible national dream into an achievable regional imperative.

Nyerere argued that political alliances must be supported by economic unity. This idea was central in his opening address to the 1970 preparatory meeting of the NAM Conference in Dar es Salaam (Nyerere, 1974). He framed the core message of non-alignment as ‘asserting the right of small or militarily weaker nations to determine their own policies in their own interests.’ He insisted that this political right was hollow without economic backing and argued that economic weakness is what allows the ‘Big Powers’ to impose their will on weaker nations, even without using military power. He identified common deficits of capital and technical expertise across the Global South that are hindering its ability to break from economic weakness. Accordingly, Nyerere contended that NAM must become an economic alliance as well. He envisioned practical examples of shared industrial investments, joint infrastructural projects and preferential trade agreements designed to build productive capacities and create mutually beneficial markets to fuel the NAM’s original commitment to genuine political independence.

This vision was further studied and detailed through the South Commission, a high-level 1987 initiative comprising prominent leaders and intellectuals from across the Global South that was founded by NAM and chaired by Nyerere himself.3 The commission’s landmark report, 'The Challenge of the South’ (Nyerere & Independent Commission of the South on Development Issues, 1990), was published in 1990 and presented an intellectual and policy framework for South-South collaboration on major development imperatives. The report outlined — among a number of other outputs — arrangements for global trade and collective action, as well as possibilities for regional integration on industrial and technological fronts, that were qualitatively distinct from the prevailing neocolonial and neoliberal models, while championing self-reliant development pathways that are forged through southern solidarity.

Nyerere’s commitment to regional integration is confirmed not just by his intellectual efforts, but by his practical political efforts towards unifying African nations such as the Preferential Trade Area for Eastern and Southern Africa. These intellectual and political endeavours were not peripheral to Nyerere’s project, but logical extensions. They were part of a deliberate strategy to construct a regional economic base that is robust enough to withstand the pressures of a hostile global order and secure a future defined by collective sovereignty.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Erosion of a Legacy: why Nyerere has faded from mainstream discourse

When the South Commission report was published in 1990, the UN General Assembly requested that all UN agencies study and take note of its recommendations. This same year the first Human Development Report, supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), was published. By that time, and since the late 1960s, Nyerere had published several books with Oxford University Press, some of which had received significant praise from reviewers. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Nyerere’s name was well known in circles concerned with governance and development in the South, including the relevant academic circles in the North. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Nyerere was still influential in circles concerned with South-South collaboration. However, starting in the mid-1990s, his contributions became less known, largely fading by the turn of the millennium. This coincided with the era by which the neoliberal offensive had consolidated its stranglehold on African politics and in scholarly circles of development studies, in concert with the reign of structural adjustment programs (SAPs) and the dominance of development discourses promoted by the IFIs. There were, of course, small ‘pockets of resistance’, in circles of development scholarship and development policymaking, that continued to produce relevant literature documenting those ‘dark times’ for African development (e.g., Adésínà, 2009; Mkandawire, 1999, 2001). But the overall picture was bleak.

By then, the dominant atmosphere was the antithesis of Nyerere’s anti-imperialist, pan-Africanist, socialist stances on development that promoted the developmental state model, industrial policy, self-reliance and South-South collaboration. IFIs become more emboldened by political and economic discourses that discouraged Nyerere’s model. From time to time, Nyerere’s name and legacy were given honorary mention and ceremonial acknowledgement, but that was it. Subsequent generations of African development scholars (especially economists), African decision makers, African NGO directors and ‘activists’, and IFI consultants, barely spoke of Nyerere and his legacy. Many have not even encountered his work.4 Indeed, such treatment did not only target Nyerere’s legacy, but in different degrees the legacies of several African leaders of national liberation, like Amilcar Cabral, Robert Sobukwe, and others. More recently, when parts of Nyerere’s legacy are mentioned, including the Ujamaa period of Tanzania, they are mostly presented as parts of negative narratives — inflating failures and undermining successes.

Only now is that period of neglect undergoing revision. Various African development scholars and policymakers have begun to reconsider topics and perspectives from the national liberation era and early decades of political independence (Adésínà, 2009; Oqubay, 2015; Sheikheldin, 2015). Topics like the developmental state, industrial policy, African regional integration and South-South collaboration, are back on the menu (Chang et al., 2016; Cramer et al., 2020; Sheikheldin, 2025; Wade, 2018). With them, Nyerere’s legacy is witnessing a revival through new, both appreciative and critical, lenses.

Blind Spots: critical engagement with Nyerere's legacy

Any appreciative lens of the Nyerere legacy also should be critical. This is a way of building upon the positive insights and successes while revising the theoretical and practical shortcomings. In this section, we briefly highlight some main points of critical engagement with Nyerere’s legacy.

One of the main theoretical and strategic blind spots in Nyerere’s philosophical foundations was the early failure to recognise class conflict within independent Tanzania. In his foundational writings, like the Arusha Declaration, Nyerere treated newly independent Tanzania as a class-conflict-free-zone that remained unpolluted by the emergence of conflicting classes in post-colonial societies. Nyerere saw an opportunity to restructure before capitalist relations of production emerged. However, several sincere scholars of Nyerere’s legacy consider this to be one of the main problematic aspects of his theoretical work, given that Tanganyikan/Tanzanian society already demonstrated the emergence of post-colonial class contradictions (Rodney, 1972; Shivji, 1970). Such theoretical and strategic shortcomings were surely reflected in planning and decision-making.

Additionally, the forced villagisation phase of Ujamaa — discussed earlier in this article — has been the foremost target of criticism of the Ujamaa project and the entire Nyerere legacy. While the forced villagisation phase proved a serious inconsistency in the praxis of Ujamaa, and for that reason deserves criticism, there are studies that give a balanced account of the Ujamaa project in general (Freyhold, 1979; Hydén, 1980). Here there are two important aspects to highlight. The first is that forced villagisation has recorded ‘successes’ in other countries —achieving what it set out to do, which is to have the rural peasants produce a high surplus that the state can then use to invest in economic transformation and industrialisation in ways that allow for the provision of public services and development of infrastructure. Collectivisation in the USSR (Davies, 1980) and China ‘succeeded’ in that sense – i.e. achieved the goals behind their design – and exercised more coercion than the forced villagisation phase of Ujamaa. In that sense, forced villagisation itself cannot be described as ‘the reason’ for the failure of Ujamaa5. The second aspect is that the Ujamaa scheme began with voluntary villagisation, with relative success. However, studies by Freyhold (1979), Hyden (1980) and others highlighted various external factors — including an unexpected long drought period in Tanzania and problematic interventions by agencies like the World Bank — that contributed to increased pressure. Additional factors included the slowing down of the rate of voluntary villagisation (contrary to the early phase of Ujamaa). Eventually, and after that initial success, the Ujamaa scheme struggled. Forced villagisation was a rescue attempt that did not provide the desired effect, but nor was not the reason for the failure itself. In this context, the relative success achieved by Ujamaa still carries as many lessons as the eventual failure.

Some studies highlight the dissonance between strategy and management in Ujamaa as another shortcoming of the Nyerere legacy (Sheikheldin, 2015). This argument points to technical and managerial shortcomings. Indeed, some of these same technical/managerial shortcomings were even highlighted by Nyerere himself. These include his own reflections on the hastiness of nationalising some industries before making sure that the Tanzanian public sector has the human and institutional capabilities to nationalise them. This also opened a back door for the foreign companies which previously owned these industrial enterprises to return via management contracts.

Another general criticism is that, despite Nyerere's preoccupation with combating conditions that foster corruption and compromised political leadership, he ultimately did not succeed in reproducing high calibre strategic and moral leadership within the ruling elite. As some scholars highlight, it was quite telling that by the time Nyerere stepped down from the country’s presidency, no one from the ruling party's high ranks was willing to openly defend his project. In his later days, Nyerere became more aware of the need for transformations within the state apparatus and ruling elite, as well as in the overall socio-political and socioeconomic landscapes. In 1995, in a general meeting of the ruling party (CCM), he famously said, ‘Watanzania wanataka Mabadiliko; Wasipoyapata ndani ya CCM, watayatafuta nje ya CCM’ (translated roughly to: ‘Tanzanians want change, and if they don’t find it within CCM they will seek it outside CCM).

Overall, Nyerere’s blind spots are themselves profoundly instructive. They teach us that any economically progressive policy must be designed with a clear-eyed analysis of national power structures to avoid being co-opted by comprador bourgeoisie and rentier classes, or by a version of ‘development' actively promoted by neoliberal institutions and powers. Additionally, even when theory is sound, without a good strategy the theory cannot prove itself. Furthermore, without effective implementation, and building capabilities for implementation, no strategy can prevail. In dealing with Nyerere’s legacy, and the legacies of other important visionaries from our past, we do well to remember the broad guideline: ‘Vision inspires, practice teaches’ (Shivji, 2008).

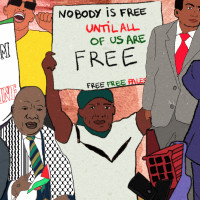

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Reclaiming a Legacy: Nyerere's compass for a new Global South

The structural threats that Nyerere diagnosed in the 1960s have solidified into the shackles constraining development across the Global South today. The perils of economic dependency, the failure of the neoliberal project, and the foundational link between national sovereignty and human freedom, are not historical footnotes but contemporary realities. In fact, even as neoliberal discourse began to lose ground on scholarly and experiential fronts, it increased its stranglehold on political power. The debt burden of our nations has worsened, granting IFIs unprecedented leverage to dictate domestic policy. And while the unipolar moment of a single 'Big Power’ may be fading, the emerging multipolarity does not guarantee emancipation. Without deliberate collective strategies and renewed initiatives of collective sovereignty that learn from NAM, the South Commission, and other experiences, the Global South risks merely swapping old masters for new ones.

New existential crises further compound these persisting challenges, including: the escalating uncertainties of climate change, displacement caused by war and conflicts and pandemics. Such emergencies have, in our recent history, intensified the imperative of self-reliance in strategic commodities and the necessity of robust and state-guaranteed social welfare systems.

In this complex landscape, Nyerere’s dialectical conception of freedom and development can serve as an indispensable compass for crafting industrial policy. It directs us toward people-centric models that prioritise both social and economic rights. His philosophy, guided by the overarching objective of expanding freedom, provides a critical framework for navigating the fine line between development and disenfranchisement. It challenges us to chart pathways of industrialisation that do not culminate in the limitation of freedom through environmental collapse, resource wars or inequalities in wealth distribution. Furthermore, his extensive experiments with communal ownership, workers ownership and direct democracy, even if not all successful, still provide a vital repository of practical knowledge. They offer, for instance, critical insights into our contemporary attempts to resolve the enduring questions of state intervention and democracy. As Nyerere himself presciently highlighted, ‘if the people are not involved in public ownership and cannot control the policies followed, the public ownership can lead to fascism, not socialism. If the people are not sovereign, then they can suffer under dreadful tyranny imposed in their name’ (Nyerere, 1968b).

The relevance of Nyerere’s proposals in terms of regional integration are similarly magnified in the current moment. In the age of fragile global supply chains and weaponised economic tools like sanctions and tariffs, the logic of collective self-reliance and South-South cooperation in an autonomous fashion (i.e., not subordinated to the empire) is a strategic necessity. Additionally, while Nyerere’s specific tactics of agrarian led industrialisation may not form a universal blueprint, his methodological approach to designing an industrial road map that strategically balances available resources with defined developmental goals, stands as powerful evidence for the fruitfulness of appropriate, context-specific industrial policy.

There is a critical intellectual imperative to repatriating the contributions of ‘Mwalimu’6 J. K. Nyerere in development and industrial policy debates. His legacy is not a mere relic rendered to the archives, but a living tradition of Southern socialist philosophy, and a rich, critical and practical resource for any project that seeks to forge a future where freedom is the tangible outcome of a just economic order.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

View series-

Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

Publication date:

-

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

Publication date:

-

Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Publication date:

-

Sustainability fantasies/genocidal realities Palestine against an eco-apartheid world

Publication date:

-

Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

Publication date:

-

From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024

Publication date:

-

The circus of academic complicity A tragicomic spectacle of evasion on the world stage of genocide

Publication date:

-

India, Israel, Palestine New equations demand new solidarities

Publication date: -

Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation

Publication date:

-

From the Favelas and Rural Brazil to Gaza How militarism and greenwashing shape relations, resistance, and solidarity with Palestine in Brazil

Publication date:

-

Yalla, Yalla, Abya Yala Reaching out to Palestine from Latin America in times of genocide

Publication date: