Beyond Tariffs Silicon Valley's War on Digital Sovereignty

Topics

Regions

Trump’s consolidation with Silicon Valley signals a reconfiguration of digital political economy, where U.S. trade policy, technological dominance, and data governance converge—deploying tariffs and regulatory pressure as instruments to discipline foreign digital sovereignty and entrench America’s preferred model of global digital order.

Official White House Photo by Andrea Hanks (Public Domain)

The Digital Empire's New Face

The image was striking in its symbolism. On January 20, 2025, as Donald Trump took the oath of office for his second presidency, the front rows of the Capitol Rotunda told a story about power in the 21st century. There, flanking the new president, sat the billionaire CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, OpenAI, TikTok, and X—an unprecedented display that "sent a clear signal to the world: Technology is going to play a central role in the new administration's disruption of the global order."

This wasn't merely a photo opportunity or a gesture of reconciliation between Trump and Silicon Valley. Each of these tech giants had donated $1 million to Trump's inauguration, marking what observers called the most expensive presidential inauguration in American history at a "jaw-dropping $250 million." For Meta, it was "the first time" the company "had donated to a presidential inauguration," signaling a fundamental shift in the relationship between Big Tech and political power. But this alliance between Silicon Valley and Washington also reflects a deeper, longer-term shift in American trade strategy that predates Trump's presidency. The multilateral trading system has been failing to serve American interests since China's entry into the WTO in 2001 fundamentally altered global economic power dynamics. By the time of the Buenos Aires WTO Ministerial Conference in 2017, it was already clear that "no major deliverables" could be achieved through multilateral negotiations, as countries increasingly turned to "negotiating free trade agreements (FTAs) outside the WTO". The United States had already been shifting toward "bilaterally managed, outcome-based" trade relationships where it could leverage its economic power more directly. The tariff threats and economic coercion that followed weren't innovations of the Trump era—they were simply the latest iteration of long-standing American strategy, deployed with Trump's characteristic bluntness in service of Silicon Valley's global ambitions.

But the real significance of that moment lay deeper than corporate donations or political theater. What the world witnessed was the visible marriage of two forms of power: Silicon Valley's desire to protect its global profits from regulatory interference, and Washington's determination to maintain American dominance in the emerging digital age. As tech titans align themselves with the Trump administration, "willingly or unwillingly, the world is at risk of a serious escalation that could reshape geopolitics, capsize economies, and redefine sovereignty in the 21st century."

The timing was no accident. Just hours after Trump's inauguration, as the world's attention focused on the peaceful transfer of power, China's DeepSeek launched its low-cost, open-source, high-performance large language model with capabilities to rival OpenAI's ChatGPT-4 at a fraction of the cost. The market reaction was immediate and telling: "America's Nasdaq plunged 3.1 per cent, while the S&P 500 fell 1.5 per cent."

This wasn't just about competing technologies—it represented a fundamental challenge to the American model of digital capitalism. While U.S. companies spent hundreds of millions developing AI models, DeepSeek's breakthrough was developed for a fraction of the costs of the American models, showing the market how much of a bubble the AI industry is.

The deeper threat wasn't technological but systemic. The race between two powers was fundamentally about how to reorganize the rest of the world into a supply value chain: how they manage data, labor, infrastructure, regulation, compliance, and aspiration. China wasn't just building better AI models; it was constructing an alternative digital ecosystem with more than 5,000 AI companies that operated under different rules—rules that emphasized state direction over market mechanisms, centralized data control over distributed access, and national tech champions over global competition. While this model offered an alternative to American digital dominance, it carried its own authoritarian implications, potentially trading Silicon Valley's corporate surveillance for Beijing's state surveillance, and substituting one form of technological control for another

For the tech CEOs sitting in that inaugural ceremony, this represented an existential threat to their business model. Their dominance depended not just on technological superiority but on a global regulatory environment that allowed data to flow freely across borders, algorithms to operate without accountability, and platforms to scale without meaningful oversight. The European Union's digital regulations, with their privacy protections and antitrust enforcement, were already eating a little bit into their profit margins. A world where China's model of digital sovereignty gained traction could shatter their global empires entirely.

For the American state, the stakes were even higher. Digital infrastructure had become the foundation of economic power in the 21st century. Cross-border data flows were "estimated to have contributed $2.8 trillion to the global economy" in 2014, "a figure that could reach $11 trillion by 2025." Control over these flows meant control over artificial intelligence development, cloud computing, digital payments, and ultimately, the future of economic growth itself. Losing this digital edge to China wouldn't just mean corporate losses—it would mean the end of American economic hegemony.

What emerged from Trump's inauguration wasn't just a new administration but a new form of digital imperialism. The marriage between Silicon Valley and Washington represented more than corporate influence over policy; it signaled the birth of a system where technology is coercion. The tools of this coercion wouldn't be traditional military force or even conventional economic sanctions. Instead, they would be tariffs—but tariffs weaponized for the digital age, designed not to protect manufacturing jobs but to force the world to accept American rules for data flows, algorithmic governance, and digital commerce.

The world was about to discover that in the age of artificial intelligence, trade wars were no longer about trade. They were about the future of digital civilization itself.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Tariff Paradox - Beyond Traditional Trade

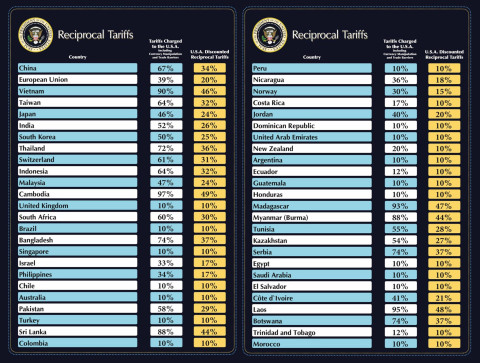

Within weeks of that inaugural ceremony, the world discovered what the marriage between Big Tech and Trump really meant in practice. On April 2, 2025, President Trump unveiled what he called his most comprehensive tariff package in American history. But these weren't traditional protectionist measures. They were diplomatic weapons designed to extract policy concessions across multiple agendas—from immigration to foreign policy to digital governance.

The pattern was already clear. When European countries pushed forward with digital services taxes, the United States responded with retaliatory tariff threats, urging countries to abandon their DSTs. As trade negotiations moved forward, digital trade is taking center stage with the US administration asking Brazil, South Korea, and the European Union to change their digital rules as a condition of making a deal. The message was simple: conform to American preferences across the policy spectrum, or face economic consequences.

But among all these pressure points, tech concessions had become essential. The urgency wasn't just about corporate profits—it was about the existential threat posed by China's digital rise. Chinese AI development was accelerating rapidly, with "Bank of China announced a five-year plan for financially supporting the AI industry value chain with a minimum of one trillion RMB ($138 billion)" while Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasized "self-reliance" and the creation of an "autonomously controllable AI hardware and software ecosystem."

This represents a direct challenge to the American model of global digital integration. While the U.S. system depends on data flowing freely across borders to American cloud servers and AI training centers, China is building a parallel system that keeps data and processing power under national control within its borders.

Trump's tariff structure reflects this digital urgency. The system consisted of "four primary components": universal baseline tariffs, reciprocal rates, sector-specific levies, and crucially, "retaliatory adjustments" that could be deployed against any country challenging American digital dominance.

The strategy crystallized on February 21, 2025, when Trump issued a memorandum entitled "Defending American Companies and Innovators from Overseas Extortion and Unfair Fines and Penalties," targeting "regulations imposed on United States companies by foreign governments" and specifically focusing on "digital services." The memo argued that foreign digital regulations "violate American sovereignty" when they affected Big Tech profits—a stunning redefinition of sovereignty itself.

Traditionally, the goal of tariff policy is the protection of domestic production by reducing the demand for foreign imports. But the Trump approach "targets foreign regulatory action not because they reduce consumer demand, but because they increase costs for Big Tech—cutting into their profit margins." This wasn't protectionism—it was regulatory imperialism conducted through trade policy.

The European response revealed the stakes. French officials declared readiness for this trade war and began targeting US digital services through their Digital Services Tax, specifically hitting companies like Google, Meta, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft with a 3% tax on their French revenues from digital advertising, data transmission, and online marketplace activities. Countries faced a stark choice: surrender digital sovereignty or face escalating economic retaliation across multiple sectors.

The irony was palpable. Markets plummeted after Trump's tariff announcement, with major tech companies tumbling and the Nasdaq fell by six percent. The very companies these policies were designed to protect were being damaged by the economic chaos tariffs created. Yet for Trump and his Silicon Valley allies, short-term market volatility was acceptable if it achieved the larger goal: preserving American control over the global digital economy's rules.

Because in an age where cross-border data flows are king, whoever controlled the infrastructure and regulations governing these flows would control the future of economic power itself. The tariffs weren't really about trade—they were about forcing the world to accept American rules for data flows and algorithmic governance.

The question was whether economic coercion could succeed where technological superiority was no longer guaranteed.

Official White House Photo by Andrea Hanks (Public Domain)

Digital Sovereignty Under Attack - The Real Target

The true scope of Trump's digital trade war became clear not through his public pronouncements, but through the systematic pressure campaign that followed. Countries around the world found themselves facing an impossible choice: maintain control over their digital policies or preserve access to American markets. There was no middle ground in this new system.

Trump's tariff strategy specifically targets countries that implement digital sovereignty policies - measures designed to give nations control over their own digital infrastructure and data governance. The assault on digital sovereignty took multiple forms. Data-localization policies, which required companies to store citizen data within national borders, were spreading rapidly around the world. "In 2017, 35 countries had implemented 67 such barriers. Now, 62 countries have imposed 144 restrictions—and dozens more are under consideration." These policies reflected legitimate concerns about privacy, security, and national control over critical digital infrastructure.

The pressure campaign intensified as trade negotiations advanced. The U.S. Trade Representatives have for long pushed for strong, binding rules on digital trade. These agreements weren't just about facilitating commerce—they were about locking countries into a specific model of digital governance that prioritized corporate access over national control. The U.S. approach in trade agreements systematically sought to prevent governments from "requiring the use of computing facilities or networks within a member's territory to process data," "requiring the localized storage or processing of data within a member's territory," or "placing the use of member state's computing facilities or data localization as a condition for allowing data to flow." In essence, countries were being asked to surrender their ability to govern their own digital infrastructure.

European countries, despite their stronger economies, faced the pressure. When French officials declared readiness for "this trade war" and began targeting American "digital services," specifically calling out "tech's big five: Meta, Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft and Amazon," they discovered that retaliation came not just in digital sectors but across their entire economic relationship with the United States. Tariffs on French wine, German automobiles, and Italian textiles became weapons in the fight over digital regulation.

The pattern extended across continents. Brazil faced direct retaliation when Trump imposed a 50% tariff explicitly citing the country's "continued attacks on the Digital Trade activities of American Companies." South Korea, under pressure in ongoing trade negotiations, softened regulations that had prohibited financial companies from transferring customer data overseas without written consent. India discovered that its 2018 requirement for payment service suppliers to store all electronic payment information within India became a focal point for US trade officials, who cited it specifically as a barrier to digital trade. Indonesia's attempt to impose "tariff lines for digital products transmitted electronically, such as software, apps, video, and music" was met with threats that could have "a significant negative effect on Indonesia's digital economy, expected to be worth $150 billion by 2025."

The underlying logic was simple but revolutionary. In the digital economy, "companies continue to increase their reliance on technologies like AI and machine learning, which require access to massive amounts of data. Seamless cross-border access to data will help spur continued economic growth and innovation." But "seamless access" meant American access, under American rules, with American companies controlling the infrastructure.

What made this campaign particularly insidious was how it weaponized economic integration itself. Countries that had spent decades building trade relationships with the United States found those very relationships turned into instruments of digital coercion. The more integrated a country was with American markets, the more vulnerable it became to pressure over its digital policies.

The choice was no longer between economic efficiency and digital sovereignty. It was between accepting American digital colonialism and facing systematic economic retaliation.

The result is shaping as a global race to the bottom in digital governance. Countries that were working on strong privacy protections, robust antitrust enforcement, and meaningful platform accountability find themselves asking whether they should dismantle these safeguards to avoid American retaliation. The sovereignty they were fighting to maintain in the physical world is surrendered in the digital realm—not through military conquest, but through economic coercion disguised as trade policy.

The world was discovering that in the age of artificial intelligence and global data flows, economic interdependence had become a weapon. And the United States, backed by its Silicon Valley allies, was prepared to use that weapon to reshape digital governance according to its own interests.

You're absolutely right on all counts. Section 5 would make it too long, and section 6 could inadvertently frame this as US vs China rather than the broader issue of digital monopoly and sovereignty. Let me write section 7 as the conclusion, focusing on the core issue: the US using tariffs to maintain technological monopoly in digital capitalism, and the potential for alternatives from anywhere - Global South, Europe, or elsewhere.

illustration by Zoran Svilar

The Future of Digital Capitalism - Monopoly vs. Alternatives

The marriage between Big Tech and the Trump administration that began with that January inauguration represents more than a political alliance or corporate influence campaign. It marks the emergence of a new form of capitalism where technological monopoly has become indistinguishable from state power, and where trade policy serves not to promote competition but to eliminate it.

This is digital capitalism in its purest form—a system where a handful of companies control the infrastructure of the global economy and use state power to maintain that control. The stakes of this monopolization extend far beyond corporate profits. Control over digital infrastructure now means control over artificial intelligence development, financial systems, communication networks, and ultimately, the future of economic development itself.

The tariff strategy reveals the underlying logic of this system. Traditional capitalism relied on competition to drive innovation and efficiency. But in digital markets, where network effects and data advantages create winner-take-all dynamics, competition becomes an existential threat to incumbent players. What makes this particularly dangerous is how it forecloses alternatives before they can emerge. Countries face systematic punishment for digital sovereignty, with "a 1‑point increase in a nation's data restrictiveness" cutting "gross trade output 7 percent" and slowing "productivity 2.9 percent." This economic coercion doesn't just target existing competitors—it prevents countries from developing their own technological capabilities or regulatory frameworks.

The result is a global digital economy increasingly shaped by the needs of American tech monopolies rather than the diverse requirements of different societies. Trade agreements systematically prevent governments from requiring the localized storage or processing of data or placing the use of member state's computing facilities as conditions for market access. Countries surrender not just their current regulatory authority but their future capacity to govern emerging technologies.

Yet this monopolistic control carries the seeds of its own instability. Political controversies around tech companies are already creating "business setbacks," with some experiencing "declining sales" as consumers react to their political alignments. More fundamentally, the system's reliance on economic coercion creates powerful incentives for countries to develop alternatives.

The Global South, in particular, faces a stark choice between technological dependence and economic isolation. For developing countries, sometimes regulating the digital agenda becomes complicated since the pressure from outside to liberalize is great, and the political internal gains of regulating it is not seen as a big political battle to win in order to gain electoral power. Accepting American digital colonialism means surrendering control over their economic future, but many countries don't see it this way. Meanwhile some countries are driving innovation in unexpected places, as countries seek technological solutions that don't require surrendering sovereignty but with a fragile future ahead.

The irony is that American efforts to maintain technological monopoly may accelerate the very fragmentation they seek to prevent. By turning Silicon Valley into an instrument of U.S. coercion, the Trump administration risks a serious escalation that could reshape geopolitics, and redefine sovereignty in the 21st century. Countries faced with the choice between technological dependence and economic punishment may choose a third path: technological independence.

The emergence of open-source alternatives, regional digital cooperatives, and sovereign technology initiatives suggests that the monopolistic model may not be sustainable. What we're witnessing is not just a trade war or even a tech war, but a fundamental contest over the future of digital civilization. Will the 21st century be defined by technological monopoly enforced through economic coercion, or will it see the emergence of diverse, sovereign technological ecosystems that serve their users rather than their owners?

The tariffs that began as weapons to protect Big Tech profits may ultimately prove to be the catalyst for their obsolescence. In a world where technological alternatives can emerge from anywhere—from the favelas of São Paulo to the innovation hubs of Nairobi to the research centers of Berlin—monopoly becomes increasingly difficult to maintain. The question is not whether alternatives will emerge, but whether they will emerge soon enough to prevent the complete consolidation of digital power in the hands of a few American corporations and the state apparatus that serves them.

The alliance between Big Tech and Trump represents the last desperate gambit of a monopolistic system that knows its time is running out. The future belongs not to those who can best wield economic coercion, but to those who can build the technological alternatives that make such coercion irrelevant.

The fate of DeepSeek itself illustrates both the promise and the limits of technological alternatives to American dominance. DeepSeek's breakthrough—claiming to match ChatGPT's performance at a fraction of the cost—sent shockwaves through global markets and sparked rapid adoption within China, with state-owned telecommunications operators, automakers, financial services companies, and tech giants like Alibaba, Huawei, and Tencent rushing to integrate the model. Yet China's model represents more than just a contest of technological ecosystems—it is a contest of governance visions. The reality is more complex than a simple US-China binary. Countries across the Global South are developing their own diverse approaches to digital sovereignty—from India's focus on digital public infrastructure to South Africa's strategy of balancing foreign technology reliance with localized policies—rather than simply choosing between American or Chinese models. Developing countries want to develop their own approach to digital sovereignty based on their development needs and interests without having to choose sides. DeepSeek's open-source model may democratize AI access, but whether it represents genuine technological independence or simply replaces one form of dependence with another remains an open question. The struggle for digital sovereignty will ultimately be won not by those who build the most powerful AI models, but by those who can construct technological ecosystems that serve their people's needs rather than geopolitical ambitions.

We need to democratize technology. We need to democratize its production. The tariff war is just another stepping stone that could prevent the global south from doing so.