Breaking with the war parties in Sudan

Topics

Regions

The two warring parties have been able to perpetuate the devastation in Sudan because they have been legitimised, especially by the international community. Peace will return when popular democracy and revolutionary politics, embedded in practices of the 2018 revolution and today’s grassroots ‘emergency rooms’, become the pillars of the Sudanese state, argues Sudanese activist in an interview with TNI.

Map credit: Al Jazeera / Creative Commons

What’s the current situation in Sudan?

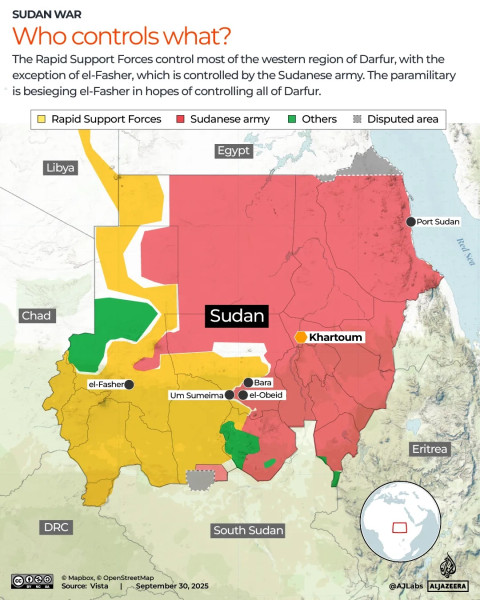

A*: The country is mostly now controlled by two armed groups and their allies. You have the Sudanese Armed Forces, SAF, and the militias allied with it who control the northern and eastern parts of Sudan while the RSF, Rapid Support Forces, and other militias allied with it control the Western areas.

Just over a month ago, RSF took control of El Fasher after a two year siege, which hit the news with photos and videos of RSF atrocities, often documented by themselves. From SAF’s side, there is news every day of prosecutions and death sentences for collaboration. Currently, battles are taking place over El Obeid. We wake up every day to news of one side kicking the other out of one village or another with all the suffering that people are subjected to.

The map gives us the image of the military situation, but it also includes other useful indicators. So, for example, you can see the very long, 2000 kilometre contact line between the two main forces, which shows the fragility and the volatility of the situation because an attack can take place by any side, at almost any point in this line, at any time. We can also see from the map that all the major armed groups control vast lands and also control some of Sudan's international borders. While RSF seems to be the force extending its control right now, earlier this year, SAF managed to take over the capital and was seen as having the upper hand. Both SAF and RSF have also been encouraging the creation of tribal militias in their areas to fight with them or on behalf of them. So volatility and fragility are the characteristics of the military situation, but as all sides have significant leverage and power it also means that this war is far from over and probably also far from its peak.

This has led to extreme humanitarian suffering. Tens of thousands killed, 12 million displaced, four million refugees. Sudan is the planet's largest immigration crisis.

The war has also had a catastrophic impact on the economy. There are two main reasons. First you have the centralisation of development in Khartoum, where a quarter of the population live, and all other regions are marginalised. This is one of the root causes of instability in Sudan and also means that a war in the capital paralyses the entire country, because all the banks were in the capital, all major service infrastructure was controlled and operated from the capital and all road roads pass through the capital.

Second, you have the way the RSF has used its control for looting. As the paper by Joshua Craze and Raga Makawi shows the disintegration of the Sudanese economy has benefited the RSF, turning them into an ‘entrepreneurial system of predatory accumulation’. Key resources have also been split and disintegrated. Gold mining has been split between RSF and SAF; RSF has controlled the major agricultural land while the only port is under the control of the army (SAF). Meanwhile the state under the control of the SAF government has mostly stopped paying salaries for its employees, leading to inflation, loss of income and unemployment. So a teacher's salary right now is less than 20 American dollars a month .A shwarma sandwich costs five American dollars, so you can imagine how difficult the situation is for so many people.

The horrors we have seen in El Fasher were long predicted. Why was it allowed to happen?

I think El Fasher was allowed to happen because those with the power to stop it gained more by allowing it. The RSF ignored all the calls to stop, because no-one could physically or financially stop them. As the largest city of the region, it was strategic for them to capture. And SAF was okay to use people as shields; even aid drops to the city while it was under siege largely benefitted their soldiers. They also benefited nationally from the images of the brutality of the RSF and the propaganda they have done as a result of the siege and massacre. When the SAF forces left, I didn't seen a single civilian coming out with them. SAF leaders easily fled while civilians had to come out of El Fasher on foot and faced brutal attacks. The ethnic ties between the residents of El Fasher and major armed movements allied with SAF increased the value of controlling the city for both sides and this unfortunately came at the cost of the lives of these residents themselves.

How did we get to this moment of war and brutality?

Before the war, Sudan had been in international news for the protests that took place in late 2018 to mid 2019 against injustice and dire economic conditions. Protests erupted against the dire economic conditions and specifically the end to subsidies of wheat, which doubled bread prices overnight. We had 60% inflation at the time and were governed by a military dictatorship that ruled Sudan for 29 years. The people’s demands were for the end of military rule and a civilian government, a bottom-up approach to governance. The protests became known as the December revolution.

We organised through neighbourhood resistance committees, instead of centralised protests which made it difficult for the security forces to attack. The protests grew over five months and became massive enough to start encampments surrounding the military headquarters in 13 of Sudan's 18 states.

The popular pressure forced the heads of the security forces to overthrow the president and set up a military council made up the heads of the Sudanese armed forces, RSF, national intelligence and other security forces. The council was rejected by the public, but received regional and financial support from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. They also found some recognition by legacy political parties who chose to enter power sharing negotiations with the military despite loud and clear public rejection of any form of military rule. Tensions grew between the public demands on one side and the compromises of the elite on the other side, until the military council opted to solve this tension via violence. It ended the encampments with massacres where hundreds died in one day and thousands remain missing to this day.

Nevertheless, the negotiations continued and the power sharing agreement was signed between the military council and the legacy parties, which created the transitional government of Sudan in late 2019. That came with the blessings of the regional and international powers like the EU, the US, Saudi, the UAE and Egypt. This pattern was repeated in coming years where armed groups in Sudan are rewarded for their violence with power and with legitimacy by the international community.

The transitional government itself was a tool of the counter-revolution. It executed the same economic liberalisation policies of the ousted president, all with the support of the international community. They also shielded the heads of the military council from any accountability for their crimes.

And this created a growing cleavage between the public and the transitional government. But before ending the second year of transitional government, internal divisions among the elite gave us another military coup. The coup was led by the heads of the SAF and the RSF, the two war parties, and was rejected by the public. They stood behind the resistance committees, which organised protests that paralysed the government. They were not even able to appoint a cabinet for the entire year.

The resistance committees also evolved politically and organisationally, producing a political charter based on deliberations among more than 8,000 committees across the country. The product, the charter itself, is not flawless. It included compromises with the state. It lacked a revolutionary theory of the state and of the struggle, and demoted their own role to exercising pressure on existing powers and systems rather than being organisers for a new system. In my opinion, the lack of a revolutionary analysis of the state and an understanding of the power of the organised people,was the main reason a lot of the energy of the Sudanese resistance front was wasted. Nevertheless its roadmap for bottom up governance was much better, even technically, than anything the international community or the local elite ever presented in Sudanese politics.

However, the international and regional actors failed to heed their demands, facilitating negotiations between the coup and the legacy parties again, and pushing for a power sharing structure. The resistance committees rejected this as they knew legitimising violence would only lead to more violence. This is the main reason why war takes place in Sudan, because it is accepted and legitimised by local and the international elites. Finally during these negotiations, another split took place and this time it was inside the military council between the RSF and SAF, which led to an outbreak of war in April 2023. Technically, the war started over technicalities of the power sharing structure, but it's actually a war over power and a continuation of the pattern of seizing power through violence, whether it comes in the form of a coup or a massacre or a war.

What happened to the Resistance Committees and the resistance front as war broke out?

As I mentioned earlier the centralisation of power and infrastructure has also affected international aid organisations. Their systems collapsed with the fall of the capital, which meant they were not capable of reaching people in war zones or providing for the displaced. So it was the members of the resistance committees that responded by creating ‘emergency response rooms’ (ERs). They started by providing health services, communal kitchens and shelters for displaced people fleeing war zones. Many then started to provide education, services for children, psychosocial support, work opportunities in some cases, and many are still providing for people that have been suffering for almost three years now. They remain up until now, the most important and the most geographically spread social infrastructure in comparison to the state or the international aid organizations.

They initially depended on their own resources and donations from the Sudanese diaspora, as well as donations from Sudanese people inside the country. But later, they also started receiving grants from International NGOs who realized that they're not able to deliver support the way that the emergency rooms can.

This of course, comes with a lot of risks of co-option and ‘NGO-isation’ of this model as you can imagine. But their model is a proof that bottom-up governance is more successful than elitist models. And not just in democratising governance, but even technically in terms of efficient service provision.

Unfortunately the lack of a solid revolutionary political theory again has its impacts, because it limits the model to temporary solutions without exploring its potential and its capacity to evolve into a new socialist governance model. I argue that practical exploration of this new model of governance is the way to stop the war. By providing people with new alternative scenarios for Sudan’s future away from the duality of the war parties, we can minimise their support. Unfortunately this is not where public opinion is right now. Even the resistance front has been co-opted by elite narratives, including those of the RSF and SAF, buying into some of the historical and nationalist grievances they play to and forgetting their criminality and brutality.

That’s why I think rather than describing this as a proxy war, it’s more accurate to call it ‘a war over proxy’, where both the military parties are fighting over the position of being the agent of international capital in delivering the resources and wealth of Sudan.

I think a revealing anecdote here is that in 2024, both RSF and the SAF exported almost equal amounts of gold to the UAE, even though it is portrayed as being the invading protector of the RSF. That’s why I think rather than describing this as a proxy war, it’s more accurate to call it ‘a war over proxy’, where both the military parties are fighting over the position of being the agent of international capital in delivering the resources and wealth of Sudan.

What can the international solidarity movement do?

It’s worth looking at the image. The banner in the background tells us that this is a communal kitchen by Taweela Emergency Room, serving newly arriving Internally Displaced Peoples (IDPs) from El Fasher. It shows us that - even amidst the atrocities - the Emergency Rooms are still working and more efficient and capable than International NGOs of reaching communities that are in need. That's why I think that the most efficient and realistic thing to be done to minimise the human suffering in Sudan is to push for more international funding to go to the Emergency Rooms. You can find some of them here: https://linktr.ee/bsonblast. ERs also need more support so they can plan beyond the immediate short-term.

In terms of ending the war, that's more complicated. Unfortunately, none of the factions of the elite are being hurt by the war and some of them are even benefiting from it. So the SAF, for example which was totally rejected by the general public is now supported by some and equated with the rule of law and patriotism. Meanwhile the RSF, who were for long a tool of the state now rule their own state controlling more than third of Sudan. Both are profiteering from Sudanese resources - particularly gold and livestock - and selling them to international regional capital with no limitations or counter pressure. They're mostly going through regional, companies, Emirati and Saudi mainly, and regional markets, even if they go somewhere else after that. The solution of the war can only come from the organised Sudanese people, and until that happens there can be truces and temporary suspensions but not a real peace.

What about arms embargoes? Could campaigns for them help?

I think by default pushing for an arms embargo is always a good thing. Minimising the chances of violence is always useful as long as you can execute it across the board. However I don’t think it would make much difference on the ground. There is already an arms embargo that is not doing much. For the RSF, for example, most of the weapons that reports indicate they receive probably comes from the UAE via Chad or Libya. Certainly it’s not via legitimate paths, so it’s difficult to stop.

Why has international solidarity with Sudan been limited?

I agree that we have not seen as much international solidarity with Sudan, even compared to during the revolution or during the early 2000s with the Darfur massacres. In part, there is the normalisation of suffering of Africans. Of course, that's a big part of it: racism. But the fact that previous atrocities and revolutionary uprisings in Sudan did receive significantly larger attention tells us that there are other reasons for the ongoing situation of a “forgotten war” in Sudan.

We also have a media model that cannot provide critical analysis covering more than one area or one topic at the time. Human suffering is covered as incidents and trends instead of manifestations of systematic and linked failures. So that meant that all solidarity energy is going to the Gaza genocide and occupation in Palestine.

Some Sudanese people and also international allies tried to present the situation in Sudan as similar to what's happening in Palestine, but that’s totally inaccurate. The 2018/2019 revolution had a clear narrative of who was the enemy, what the people of Sudan wanted, and what people outside could support. However the situation and the narrative right now is not as clear. Those asking for international support for armed forces that four years ago you were in a revolution against is not doable or understandable. So there's a lot of work for the Sudanese people to push for the alternative narrative.

For the Sudanese and international activist community, learning from Sudan’s history is necessary. We need to support critical thinking and sharing experience. Not just for the Sudanese revolution but for the one we need internationally.

*A is a pseudonym. A Sudanese activist and writer displaced by the war.