China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Topics

Escalating hostility with green-tech leader China has undermined the energy transition in Europe and the US and now could be completely derailed by a nationalist politics of climate denial. A just green transition depends ever more on combining class politics with rapid decarbonisation and anti-imperialism.

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

China’s green leap forward

In the mid-2010s, it was assumed in much western-based commentary that a re-structuring of China’s economy away from investment to consumption, following the capitalist pattern of economic development, was around the corner and inevitable. But by 2024, no such transformation was observable: China’s ratio of investment to gross domestic product (GDP) remained stubbornly above 40%, compared to around 20% in the US and the EU.

Instead, China has re-balanced in a different way. The massive stimulus in 2008 which kept the wheels turning on China’s industrial juggernaut during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) also inflated a construction- and real-estate bubble, exemplified by the slow collapse of the property giant Evergrande from 2021 onwards. As investment drained from the real-estate sector, it found a new home in another capital-intensive industry: clean-energy manufacturing.

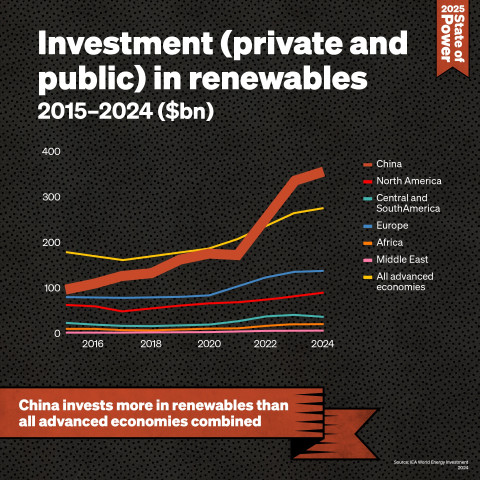

The data tells its own story. In 2023, 39% of all investment was in clean-energy manufacturing, while investment in real estate fell by 9%. A massive 40% of China’s GDP growth came from clean-energy sectors. ‘The major role that clean energy played in boosting growth in 2023 means the industry is now a key part of China’s wider economic and industrial development’, a CarbonBrief analysis concludes

ource: TNI based on IEA World Energy Investment, 2024. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-investment-2024-datafile

Behind this investment shift is the guiding hand of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In July 2024, the Third Plenum, a key five-yearly meeting of the Central Committee, called for officials to ‘make concerted efforts to cut carbon emissions’ and ‘actively respond to climate change’ for the first time. This was just the latest in a long line of policy signals from the CCP that the country’s economic future would rest on what Chinese media now call the ‘new three’ of solar, energy storage and e-vehicles, replacing the ‘old three’ of clothing, home appliances and furniture.

The critical announcement was in 2020 when Xi Jinping told the United Nations General Assembly that China would be carbon neutral by 2060, with emissions peaking ‘well before’ 2030. Since then, the Chinese state has acted to make these goals a reality. Local government has increased subsidies for major clean-energy projects. Central government made it easier for private-sector firms to obtain credit during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the largely private-sector-owned clean-energy sector taking advantage to expand rapidly. As if to emphasise the point that China’s economic strategy was shifting, there are now financial incentives for solar plants to be built on old construction sites that had been left derelict since the downturn in real estate.

These are only the latest developments in a much longer process of green-tech development since 2005, when China introduced its first law on renewable energy, requiring the grid to purchase clean energy at preferable prices. This initiative was given a major boost by the 2008 stimulus. While the surge in construction took the global headlines, 5% of the four-trillion-yuan investment was in renewables. This made clean-energy manufacturing a serious economic player in China, and with it emerged the prospect of an energy source which could both significantly reduce the country’s chronic air pollution and simultaneously cut its dependence on importing oil and gas.

From then on, the development of renewables has been aided by consistent policy support, including import-substitution policies which restrict the influence of foreign competitors. The twelfth five-year plan (2011–2015) required 80% of inputs to the production of solar cells to be ‘localised’. In 2015, the ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy, which helped steer China from a low- to high-productivity manufacturing giant, aimed for 70% of electric and hybrid vehicles sold in China to be built by Chinese companies by 2020, and 80% by 2025. This laid the basis for Chinese clean-energy manufacturers to become national, and then global, players.

This does not mean, however, that clean energy has displaced fossil fuels in China’s energy mix. While fossil fuels now make up less than half of the country’s installed generation capacity, compared to two-thirds a decade ago, in absolute terms the use of fossil fuels – coal, most importantly – has continued to rise, albeit at a slower rate. China’s energy shift is defined more by expansion than transition.

Phasing out coal is complicated by China’s energy grid, which was built for a predictable and flexible energy supply and is not well adapted to the intermittency of renewables. Whereas most Western countries rely on the less-CO2-intensive gas for this flexibility in their energy systems, China’s gas power accounts for only 5% of installed capacity, making coal the main energy source to meet peak demand. China is investing in batteries and pumped-storage hydropower to address this challenge in the energy supply in the long term, but these are unlikely to displace the reliance on coal in the foreseeable future.

Nonetheless, the data is moving in the right direction. In June 2024, renewables capacity outstripped coal capacity in China, while new authorisation of coal-fired power plants dropped by 80% in the first half of the year. There is some evidence to suggest that China’s carbon emissions may have already peaked, five years before Xi Jinping’s target.

To put the East Asian country’s green leap forward into perspective, it is worth contrasting the fortunes of solar manufacturing in China with that of the EU since the GFC. At the start of the 2010s, the EU produced 60% of solar panels worldwide, with the industry’s development aided by generous government subsidies for installation. But when the eurozone crisis hit from 2009 and austerity programmes were introduced, the subsidies were dropped, demand collapsed and solar production declined rapidly. In Spain, for instance, solar capacity fell from 2,718MW in 2008 to just 44MW one year later.

While Chinese policy support has been consistent and large, the EU’s has been haphazard and weak. China invested ten times more in solar supply capacity than the EU from 2011 to 2021, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The outcome is that while China is now the dominant player, the EU is struggling to maintain any sort of solar manufacturing capacity.

“In two years, the European installed solar PV capacity has been multiplied by two,” one 2024 study by researcher Thibaud Voïta finds. “On the other hand, the remaining European manufacturers of solar PV panels are dying.”

China now commands the solar supply chain, with a global share above 90% in every segment except cells (88%). The top ten companies worldwide providing solar-manufacturing equipment are Chinese. Moreover, China has the processing and refining capacity in the critical minerals (primarily copper and silicon) required for solar production, meaning it exercises control over the whole value chain. According to the IEA, ‘[t]he world will almost completely rely on China for the supply of key building blocks for solar panel production through 2025’.

China’s success in producing solar panels is also bringing its own challenges, however. The relentless driving down of costs in all parts of the value chain has seen the price of solar panels drop by more than 80% in a decade, creating a profitability crisis for producers. A group of solar companies have even asked the Chinese government to set a minimum price for solar panels.

In a dash for growth, in 2023 Chinese manufacturers produced three times more solar panels than the global economy could absorb, to the extent that in Europe some Chinese solar panels have been used for fencing. While the cost of solar production has fallen, the cost of installation and grid connection is rising in many countries, leaving Chinese solar producers short of buyers. CCP-controlled China may be verging on a classic capitalist crisis of overproduction.

Western politicians and regulators have depicted this ‘overcapacity’ problem in moral terms, arguing that China is ‘unfairly’ gaining market advantage through subsidies and ‘dumping’ its over-supply of cheap-labour produced green products on the US and Europe, undercutting Western competitors. This is the argument used to justify increasing tariffs on Chinese clean-energy products.

The western case against Chinese green imports is wrought through with contradictions and hypocrisies. First, western elites had no problem with cheap Chinese imports when the products were low-down the value chain, and thus no threat to their corporations, which in any case have directly benefited from cheap Chinese labour for decades. Only now that high-value Chinese technology threatens to dominate western competitors is their concern about ‘dumping'. Second, all governments accept that climate change requires at least some degree of state intervention to hasten the advance of zero-carbon technologies. Given the urgency of climate action, concerns about ‘overcapacity' should be seen as a red-herring. Finally, as we will discuss further below, the EU and especially the US have also rolled-out subsidies for the development of their own green tech firms, just like China, and have sought to protect their market leaders in many industry sectors, in the US case most famously in semiconductors.

In reality, the tariffs on Chinese green tech have little to do with fairness and a lot to do with geopolitical competition: western politicians and CEOs know that their companies cannot compete with cheaper and higher-quality Chinese clean-energy goods. But raising the drawbridge cuts them off from using China’s enormous, low-cost renewables capacity. The IEA has found that global emissions could be 15% lower by 2030 simply through fully deploying existing solar power and grid-connected batteries manufacturing capacity, the vast majority of which is in China. While the EU blocks Chinese clean-energy products from being deployed in Europe, in China they are busy getting on with it.

According to Isabel Hilton, a long-standing expert on China, in 2022 the country ‘installed roughly as much solar photovoltaic capacity as the rest of the world combined, then went on in 2023 to double new solar installations’.

Sadly, China’s progress is not shaming the US or the EU into action. Indeed, since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the watchwords in the West have shifted from ‘climate emergency’ to ‘energy security’.

Europe caught in a web of contradictions

For decades, Germany, the EU’s economic powerhouse, combined energy reliance on Russia, by importing natural gas, with geopolitical reliance on the US, through membership of NATO and the US military presence in the country. In a post-Soviet world where US hegemony was unquestionable, Germany’s contradictory dependencies were not a problem.

But German politicians had failed to notice that, at least since 2008, when the GFC struck in Wall Street and Russia fought and won a war against Georgia in the South Caucasus, the ‘unipolar moment’ of US dominance was over. The world in which Germany was unified after the fall of the Berlin Wall was only a temporary phase in the geopolitical balance of power. When Russian tanks rolled into western Ukraine in February 2022, the naivety of Germany’s strategic planners was undeniable.

Cut off from the country’s most important energy imports, Germany’s energy prices skyrocketed, as it bought more expensive liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US and the Middle East to replace the cheaper Russian gas that had been lost. Coal-fired plants, scheduled for closure, were also kept going in wake of the crisis as the country’s nuclear plants had already been closed. Under a coalition government which included the Green Party, Germany turned to the dirtiest source of fuel to keep the lights on.

The higher energy costs had a major impact on the country’s export-led economy, with industrial output in May 2024 some 15% below its 2017 peak. But in responding to this threat, Germany is once again caught in a web of contradictions. The country’s largest trade partner is China, but the US has sought to use the growing geopolitical tensions emerging from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine to swing Germany and the rest of Europe behind an anti-China trade offensive. At the centre of this tension is Germany’s most politically important industry: car manufacturing.

German cars – Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen and Audi – are known the world over for quality and reliability. But a great history does not guarantee a great future. German car manufacturers started late and hesitantly in investing in e-vehicle technology, falling behind their Chinese rivals.

Just as in the solar industry, Chinese developmentalist policies, including huge subsidies, provided the platform for the rise of the country’s car manufacturers, which previously relied on partnerships with higher-tech Western manufacturers. Now, the tables have turned. Whereas companies such as GM and BMW had become dependent on outsourcing to reduce costs, fracturing their supply chain, BYD has built low-cost, high-quality e-vehicles through vertical integration of its supply chain, right down to owning lithium mines. The results have been spectacular. In 2023, BYD sold more electric and hybrid vehicles worldwide than all German car manufacturers combined.

German car manufacturers are now at a crisis point: Volkswagen is for the first time considering closing German factories as new e-vehicle registrations have stalled in Europe’s largest economy. ‘Germany is at a standstill’, according to Ferdinand Dudenhöffer, a former professor of Automotive Economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen. ‘And things will get really tough after 2025 when the Chinese will be dominating the global market for electric cars.’

The European Commission’s response was to hike tariffs on Chinese e-vehicles, but the German government opposed this, under pressure from the country’s car manufacturers to block a tit-for-tat tariff war between the EU and China. The likes of Volkswagen and BMW know that they have more to lose from retaliatory tariffs on German cars in China, the world’s largest market, than they have to gain from limiting BYD and similar companies’ entry into the EU.

Indeed, far from ‘de-risking’ competition from China, as the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has urged European companies to do, German car manufacturers are doubling-down on their investment in the East Asian giant. More than half of the €19 billion profits made by German car manufacturers in 2023 was invested in China. These companies know that not only do they need access to China’s domestic market, but they also need to produce cars in China because that is where the cutting-edge of global e-vehicle battery technology is.

US car manufacturers are facing similar strategic dilemmas. While Tesla is one of the few US automakers which does not rely on outsourcing, Elon Musk’s company uses BYD cells in its production, and Ford and GM use BYD batteries. GM has decided to move away from the Chinese market, not because of the trade war between China and the US, but because its sales in China have slumped as it struggles to compete on the terrain of e-vehicles. German car manufacturers are desperate to avoid the same fate.

As the historian and economic commentator Adam Tooze has argued, these ‘industry dynamics’ are as important, if not more so, to geopolitics as the pronouncements of politicians like von der Leyen about de-risking. ‘In the case of major industries like car-making, the choices themselves, the industry dynamics themselves are the geopolitical vector that matters’, Tooze writes.

The EU’s anti-China offensive comes as its policy commitments on the decarbonisation of transport start to ramp up. In 2019 the EU pledged to ban the production of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars by 2035, while by 2025 car manufacturers must reduce their emissions by 15% compared to a 2021 baseline – or face severe fines.

These policies are the legacy of a different era in EU politics. Von der Leyen first became European Commission President in 2019, a time when ‘Fridays for Future’ demonstrations were all over the news and there was talk on both sides of the Atlantic of a ‘Green New Deal’ (GND) that promised to combine rapid decarbonisation of infrastructure with a social transformation of the economy. Von der Leyen responded to the pressure with her ‘European Green Deal’, which stripped out the social justice aspects of the GND in favour of seed funding and incentives to nudge the private sector into action, in what the economist Daniela Gabor called ‘a politics as usual, third-way approach’ to decarbonisation.

But in the EU of 2025, the political pressure has shifted away from the green transition and towards security. Von der Leyen was re-elected in July 2024 for a second term as Commission President after a campaign in which she promised an ‘era of rearmament’ and the building of a ‘European defence shield’, and studiously avoided talk of the Green Deal. Her parliamentary group, the centre-right European People’s Party, has called for scrapping the 2035 ICE ban and Von Der Leyen signalled in her manifesto that she backed a ‘targeted amendment’ of the law to allow for ‘e-fuels’ – biofuels which still emit carbon – to be permitted. Brussels’ powerful fossil fuel lobby is pushing for climate policies to be watered down still further.

Von der Leyen’s roll-back is short-sighted. The EU’s energy vulnerabilities stem from the fact that the continent is, along with Asia, one of two major regions that are significant net importers of oil and gas. If self-sufficiency brings about security in energy terms, then renewables are the only game in town for the EU over the long term. Unless and until the EU builds its own high-quality clean-energy manufacturing capacity, its politicians cannot afford to burn their bridges with China if the green transition is to move forward.

There is some evidence to suggest that, despite the political rhetoric, European elites are aware that they cannot do without China right now. One interpretation of the EU’s tariffs on Chinese e-vehicles is less that Brussels wants to keep China out, and more that it wants to force BYG and related companies to manufacture their e-vehicles in Europe. One study has identified 15 e-vehicle and battery-manufacturing investments made by Chinese firms in Europe, nine of which are by Chinese firms directly and six are via European companies.

But while von der Leyen is willing to play hard ball with China, she has also embraced new depths of deference to protect the US link. In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s second presidential election victory, she suggested that the EU could buy more LNG from the US as a quid pro quo for Trump not placing huge tariffs on EU exports to the US. Given the EU’s obsequiousness to Washington, we can expect that the decisive factor in future Sino-European relations – including over the technologies which power the green transition – is not what happens in the EU, but just how far the US is willing to go in its bid to curtail China’s rise.

The US and the geoeconomics of decarbonisation

Looked at solely from the perspective of climate policy, the track record of the US appears to be a model of inconsistency. Under Obama, US diplomacy was key to the Paris Agreement, while at the same time he ushered in a shale-gas revolution which made the US once again a major exporter of oil and gas. Under Trump, the US was taken out of the Paris Agreement and a visible commitment was made to a US fossil-fuel imperialism based on shale gas and LNG exports, or what Trump called ‘energy dominance’. Under Biden, the most serious commitments to building clean-energy infrastructure were made, while at the same time licensing new oil and gas developments and applying intense pressure on OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) to increase production.

Behind these seemingly contradictory shifts lies a red, white and blue thread: US geopolitical supremacy. It is geopolitics which explains the inherent tensions within a country that is the world’s single biggest producer of oil and gas, while also being a global power seeking to maintain hegemony through a period of immense change in global energy systems. When analysing Biden’s climate policy, which was closely tied to an agenda for industrial renewal, this geopolitical dimension is more important than many commentators have acknowledged.

‘Viewed from the halls of power, the anti-China orientation of US industrial policy is not an unfortunate by-product of the green “transition”, but its motivating purpose’, Grey Anderson writes. This is clearest in Biden’s major tariff hike on China, announced in May 2024, which specifically targeted renewables products. Tariffs on Chinese e-vehicles rose from 25% to 100%, batteries for e-vehicles from 7.5% to 25% and on solar cells from 25% to 50%. The US has turned to protectionist measures specifically to block the advance of Chinese goods: Japanese, Korean and European e-vehicle firms were exempt from the tariff scheme.

Anti-China protectionism is combined with ‘friendshoring’ – pushing US firms to set up in countries with low labour costs other than China. US e-vehicle firms can attract tax credits only by sourcing supplies through countries which the US has a free trade agreement (FTA), such as Mexico. Tesla started building its first $5 billion ‘gigafactory’ in Mexico in 2024. But Mexico is also attracting Chinese investment as a back-door route into the US market. Exports of e-vehicles from Mexico to the US have surged.

The centrepiece of Biden’s one-term presidency was the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). At once a historic investment in clean energy and a license to keep drilling for oil and gas for at least the next decade, from the perspective of climate policy the IRA embodies the contradictions of US ‘leadership’. But from the perspective of geopolitics, the IRA is more internally consistent: the US wants to have its cake and eat it; maintain its position as a leading oil and gas producer and catch up with China in the development of its clean-energy industry.

As Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay have argued, the IRA was ‘all carrot and no stick’: it provided generous tax credits for renewables firms to set up in the US but did nothing on the regulatory side to restrict polluters. This stands in contrast to the EU’s approach, as Brussels is constitutionally not permitted to offer direct subsidies to companies, but has wide regulatory powers to restrict carbon emissions, and to offer targeted investments aimed at decarbonising infrastructure and incentivising consumers to go green.

This is not to say that the EU’s climate policy does not contain a strong dose of geopolitics. Its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which entered into force in 2023, hikes the cost of exporting goods into the EU based on the carbon emissions cost in their production, with some of the producers most affected being from among the world’s poorest countries, such as Cameroon, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, where per capita carbon emissions are a fraction of those in Europe. A study undertaken by the Asian Development Bank found that the CBAM will do little to reduce emissions, while costing jobs and livelihoods in the global south. The report proposed ‘mechanisms to share emission reduction technology’ as a more effective measure to get producers in lower-income countries to reduce their own emissions.

The EU’s neo-colonial approach to climate policy extends to critical raw materials (CRM), for which it is highly dependent on the global south for CRM, with China the main global supplier for 34 of the 51 most important CRMs. For the other 17 CRMs, in only four cases is a member of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) the main supplier (Australia and France once each, and the US twice).

The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, passed in 2023, gives insight into how the EU aims to address its dependency on CRM: by 2030, it has set a benchmark of extracting 10% and processing 40% of its CRM consumption. The difference between the extraction and processing benchmarks is illuminating: just as in the colonial era, Brussels expects to use resource-rich countries across the Global South for the dirty work of extraction, while the EU does the added-value work of processing. The reality is that China already dominates the processing of CRMs that have been extracted from countries in Africa, an advantage that will be extremely difficult for Europe to claw back.

Many countries which are CRM-rich have already experienced the ‘resource curse’, whereby they become tied to extractivist trade relationships that ‘yield[s] slower economic growth, higher propensity for corruption and rent-seeking, and increased likelihood of political violence’, as Jewellord T. New Singh describes. That these dynamics are being repeated in the green transition as capital’s appetite for CRM grows is beyond question, and not only in the Global South: Serbia, on the EU’s periphery, has endured a major dispute over its lithium mining in the service of German big business. But some countries are learning from the past: Indonesia has banned the exporting of raw nickel and requires international companies to process mineral ores inside the country, thus developing its own processing capacities in the process.

Western countries are also scrapping among themselves for geo-economic advantage in the green transition. One clear motivation of Biden’s IRA tax credits was to attract clean-energy firms across the Atlantic. There is indeed evidence to suggest that this manoeuvre has been successful, leading the EU – which was sharply critical of the IRA – to respond with its own measures, which allow member states to ‘match’ subsidies offered by the US government, with some strings attached. These temporary measures have been combined with a Net Zero Industry Act, passed in 2024, which provides indirect incentives to European clean-energy firms: a more favourable public procurement policy and administrative support. While beggar-thy-neighbour strategies will undoubtedly improve the bottom lines of Western renewables firms (many of which are also major fossil-fuel producers), it is far from clear whether this approach is up to the task of achieving the rapid zero-carbon transition the world needs.

The US, the EU and indeed China may be spurred on by a geopolitically motivated race for green-tech supremacy, but their combined investments are still far too low in relation to the scale of the challenge. Current planned investments in clean energy are just a third of what the International Renewable Energy Agency (IREA) estimates needs to be built every year until 2030. Although $1.3 trillion of climate finance was invested in 2021/22, $6 trillion is needed by 2025 and $9 trillion by 2030, according to the Climate Policy Initiative.

What’s the hold up? As Brett Christophers has shown, the problem is not that renewables are too expensive for capital relative to fossil fuels: there is a strong case to say clean energy is now cheaper than dirty energy. The problem is that cheap energy does not necessarily produce vast profits. Fossil fuels have generally produced much bigger profits than renewables for the major energy companies, and even the large government subsidies for clean energy have not changed that calculus fundamentally.

‘If private capital, circulating in markets, is still failing to decarbonise global electricity generation sufficiently rapidly even with all the support it has gotten and is getting from governments, and even with technology costs having fallen as far and as fast as they have, it is surely as clear a sign as possible that capital is not designed to do the job’, according to Christophers.

What has bound together distinct climate strategies in Washington, Brussels and even Beijing is that the logic of capital accumulation has still prevailed, with the state limiting itself to shaping the terrain upon which profits are accumulated. What is required is an agenda for the zero-carbon transition in which the dynamics of capitalism and imperialism are subordinate to the universal interest in a future that is ecologically habitable for human life.

For a green transition that is fast, just and anti-imperialist

There is nothing pre-ordained about the working class in any country embracing the politics of a just transition or anti-imperialism. Indeed, another form of class politics, represented by the far right, is increasingly visible. Sections of capital which are invested in sustaining fossil fuels for as long as possible and pursuing an aggressive imperialist policy towards China’s clean-energy revolution convinces workers that their interests lie in a toxic mix of climate denialism, corporate protectionism and ethnonationalism.

One can see this potential among workers in car manufacturing. In the US, an ‘Autoworkers for Trump’ representative, Brian Pannebecker, spoke at one of Trump’s election rallies in August 2024, stating: ‘Chrysler and GM have already gone bankrupt once, but if we allow electric vehicle mandates to be put on this industry by the federal government, they’re going out of business again’. By ‘electric vehicle mandate’ Pannebecker was referring to the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposal that two-thirds of all new vehicles produced in the US should be electric by 2032.

With Trump’s return to the presidency, the ‘electric vehicle mandate’ will almost certainly never come to fruition, while consumer tax credits for buying e-vehicles are set to disappear. However, production tax credits are likely to remain to prevent jobs from being offshored, showing that while Trump may be anti-green he does not want to lose green jobs. As well as the ICE car manufactures like GM and Chrysler, Tesla is also likely to benefit from Trump’s policy on e-vehicles in the immediate term because unlike its rivals in the US, it does not need consumer subsidies to turn a profit on each vehicle sold. Musk’s car company will also gain from Trump ramping up Biden-era tariffs on Chinese e-vehicles. What’s good for the competitive advantage of a manufacturer like Tesla is not necessarily to the benefit of the e-vehicle industry overall, and certainly not for the wider battle to reduce carbon emissions.

It’s not only in the US where far-right politics is proving seductive to autoworkers. In Germany, the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany) has sought to tie its identity to the ICE, stating that their political rivals have a ‘hatred’ for German car manufacturers and that ‘your car would vote for AfD’. With Trump stating explicitly that he wants ‘German car companies to become American car companies’ through the carrot of subsidies and the stick of tariffs, German politicians of all stripes are under pressure to embrace a nationalist politics of their own which dispenses with anything which could threaten the competitiveness of their car giants, including green regulations.

A lethal cocktail of geopolitical headwinds and workers’ anxiety over jobs and conditions could consolidate itself in a politics that derails the green transition indefinitely. The challenge for the left is to ensure this does not happen by offering a compelling alternative to both the doom-laden politics of fossil-fuel nationalism and the tried-and-tested failures of liberal centrism. We need to tell a persuasive story which combines class politics with rapid decarbonisation and anti-imperialism.

Key to this argument is to challenge head-on the idea that autoworkers and their bosses have the same interests. The bankruptcies to which Pannebecker alluded at Chrysler and GM (which were resolved by state bailouts) were not caused by e-vehicles or Chinese competition, but by the financialisation of the two auto manufacturers which had enriched shareholders at the expense of workers. If the future of car workers’ jobs are left in the hands of corporate bosses desperate to suck out the last profits of the ICE age, these same workers will be the first to drown when that ship inevitably sinks.

A rapid transition towards e-vehicles is in the interest of US and German workers autoworkers provided that they are involved in the manufacturing process – but they are being left behind by a lack of public investment in the e-charging infrastructure consumers need and also by poor management of their companies, which have failed to adapt to the rise of the e-battery. Furthermore, car workers in the West should have no objections to using Chinese intellectual property: they have nothing to gain from an imperialist policy that seeks to block the spread of more advanced Chinese battery technology, as more expensive and less efficient battery tech in the West means lower quality in the finished product and less consumer interest.

Part of the task for the left in the West in the green transition is a familiar one: to keep their own states off the back of Global South countries, including China. The more the US, EU and the UK invest in military spending and economic sabotage tactics towards China, the more China will invest in a militarised response. A war between the US and China over Taiwan would trigger a global disaster on various fronts, one of which would be to set back decarbonisation everywhere by years, if not decades. The best form of internationalism remains anti-imperialism.

At the same time, workers involved in the green transition should seek to build class solidarity across borders, as the need for a just transition for workers is just as important in the global south as the global north. It has been reported, for instance, that the production of polysilicon for solar manufacturing in the Xinjiang region of China has occurred under conditions ‘tantamount to forcible transfer of populations and enslavement’. The ambition should be to link up workers across borders and across global value chains in order to exert maximum pressure on corporate executives and governments to ensure that workers’ rights are guaranteed in the green transition.

It is also vital to offer a vision of how the green transition could break free from the constraints of capital accumulation and market competition. What US autoworkers really need is a planned approach to the decarbonisation of transport akin to the transformation of US car factories during World War II. Whereas the state then repurposed car production for tanks and jets, this time they would be transformed to lead a shift from individual vehicles to public transport, especially in urban areas.

This would necessarily involve de-commodifying transport, a socialisation which provides efficiency gains in production as well as reducing and equalising the costs of using transport. Labour planning would ensure that workers would not have to pay the costs of any re-skilling required. Crucially, such a planned approach must also include the active suppression of fossil-fuel developments and infrastructure alongside growing clean-energy capacity: only a combination of green investment and the suppression of fossil fuels is capable of decarbonising the economy fast enough.

We have focused only on the transport sector here, but similar political and class conflicts over the green transition are raging in all the key sectors to decarbonisation, with energy, housing and agriculture being three other important areas. In all these cases, it is imperative to find a dynamic formula which combines climate and class politics.2

While this is a huge undertaking given the current balance of forces, we should be alive to the opportunities that can arise from the intertwined process of the end of fossil fuels and the end of Western hegemony, neither of which is happening anything like fast enough but both of which are underway. In the conflict and chaos that will inevitably ensue from such a radical change in the world order, the possibility of a new paradigm, where profit is replaced with planning and geopolitical rivalry makes way for cooperation, may suddenly feel like a live possibility.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: