Can China challenge the US empire?

Topics

Regions

China’s extraordinary growth has led many to assume it will soon replace the US as the world hegemon. It is important to look beyond the headlines at structural power – namely security, finance, production and knowledge – to get a more accurate view of China’s potential and limitations as a global power.

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

Structural Power in Security, Finance and Production

Security Structure

Usually even those who argue that we already live in a multipolar world order recognise that US military power is still dominant. There is no other nation that has ever had so many military assets around the planet, estimated between 750 and 1,000 (many are classified and involve ‘only’ a CIA or National Security Agency (NSA) listening post) in at least 80 countries.11 Even at its peak the British empire had bases in around 35 countries or colonies.12 There have been more than 50,000 US troops permanently stationed on both ends of Eurasia since 1945, and currently another 50,000 in the Middle East. With NATO, the US has the most expansive alliance system the world has ever seen, in addition to key non-NATO allies/proxies such as Australia, Israel, Japan, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Ukraine. They all purchase US weapons systems and share intelligence/security resources. Because of this alliance system, referencing only the US military budget of $850 billion does not capture the full extent of US dominance in the security structure – even if this budget alone is larger than the next ten militaries combined and roughly quadruple China’s, greater if we include the Departments of Energy (custodian of the nuclear arsenal), Homeland Security and NASA, among others.

Many theorists of globalisation have trouble with incorporating this US empire of bases into their conceptualisations of a ‘de-nationalized world market’, or a ‘transnational capitalist class’ above nation-states.13 So many take for granted the most powerful empire in human history as water to fish – yet this stunning success in shaping the ideological knowledge structure of liberalism renders invisible naked US imperialism even for many on the Left.

That said, China has had a naval base in Djibouti since 2017 (as do France, Italy, Japan, the UK and US), its first overseas base since the 1400s. It seems to be building another one in Cambodia. Since 2016 there have been military installations on various artificial islands in the South China Sea, and China and Russia now do regular joint exercises. China also has control of two key ports in the Indian Ocean (among others), Gwadar in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, although Pakistan still does not allow China to station military assets in Gwadar, despite much Chinese pressure.

Nevertheless, China is not militarily supporting Russia in its war against NATO-backed Ukraine; only North Korea and Iran are providing military assistance (in fact Chinese state banks have cut off Russian dollar financing). This doesn’t bode well for any potential mutual defence treaty between China and Russia, both of which are reticent to sign with others – but surely they cannot take on the US empire alone. Apart from brief conflicts in 1962 and 1967 against India and 1979 against Vietnam, China hasn’t mobilised troops since the 1950-1953 Korean War; China has never fought wars across continents or oceans. The lack of any Chinese security role in the conflagrations of the Middle East is itself revealing – whereas Russia has been deeply involved in the Syrian dirty war since 2015, and has exported missile defence systems to Iran to counter Israel.

Finance Structure

The US ensured that its currency would be the most traded in the capitalist world during the 1944 Bretton Woods conference that set up the new dollar-gold standard backed by the newly established International Monetary Fund (IMF). When President Nixon unilaterally unmoored the US dollar from gold in 1971, the US was free to balloon its balance of payments deficit, coupled with much financial de-/re-regulation as well as the emergence of the petrodollar.14 Persian Gulf states committed to recycling their dollar revenues from oil exports back into US dollar-denominated assets, especially Treasury Bills (T-Bills). This ensured that any country that wants to import oil, the fundamental commodity of industrial capitalism,15 needs to stockpile US dollars, which can only be earned via their own exports (except for the US of course, which can just print money). As all countries that rely on export-driven growth (from China, Japan, Germany to virtually all ‘emerging markets’) stockpile the dollar, they need to invest in safe-haven assets to protect their value from depreciation and the volatility of other assets (such as the stock market).

In global finance the T-Bill is considered the world’s safest asset in large part because the US state is believed to be the most able and willing to guarantee global capitalist interests.16 While expressed in terms of ‘market/political stability’, ‘democracy/rule of law’, ‘low risk’, etc, this is essentially because of US military power (no country can invade the US and overturn its bourgeois nature) and the strength of its capitalist system (very little chance for a socialist revolution to overthrow the US capitalist class).

US military power is also important to protect the petrodollar: Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi both wanted to sell their oil in non-dollar currencies but that didn’t work out well for them. Liberal economists neglect the vital role of US military power in protecting the US dollar as the de facto global transactions currency.

At 2.2% in the third quarter of 2024, China’s RMB can barely compete even with the Canadian dollar (2.7%) in global currency reserves, despite having a GDP more than eight times larger than Canada’s. To seriously challenge the US dollar China would have to reduce capital controls so that investors (whether foreign or domestic) can freely move RMB in and out of the country. But since its first major stock-market crash in Shanghai 2015, far from liberalising, China expanded its capital controls – thereby prioritising state control over internationalisation. From 2020 Xi also cracked down on private fintech including dramatically cancelling what would have been the world’s largest IPO (initial public offering) at the time, Ant Group, when its CEO Jack Ma criticised Chinese central banking policy, after which he went into hiding for several years.

Even if the Chinese state were to reduce capital controls and unleash private finance, it would still be a tall order to convince capitalists of the world that their interests would be better served by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) than the thoroughly bourgeois US state. This is not to say that China is anti-capitalist in any meaningful sense, but clearly the CCP privileges political stability above capitalist class interests, whether foreign or domestic.

There is thus little basis for capitalists of East Asia/BRICS+ (let alone the world) to rally around any potential ‘Chinese hegemony’ to support the RMB dethroning the dollar.17 Even if there were, China would still have to face the might of US military power, as the latter would certainly not sit idly by if China made serious efforts to challenge its financial power.

Production

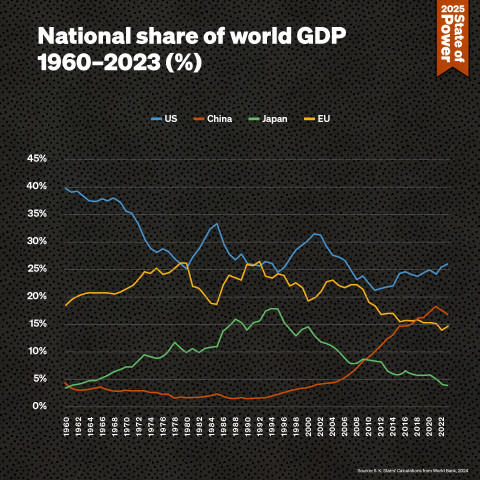

Where China seems to have gained most ground is in the sphere of global production. Figure 1 presents national/regional shares of world GDP from 1960 to 2023, in current US dollars.18 By this measure the US has clearly declined, from accounting for 40% of world GDP in 1960 to 25% by 1980, and fluctuating thereafter, reaching a 2011 nadir of 21% and rising to 26% by 2023 – a far cry from its share in the 1950s. By contrast, China’s share of world GDP began to rise continuously since Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 ‘Southern Tour’ in which he doubled down on the province of Guangdong and the free-trade zone of Shenzhen in particular as a workshop and export platform for foreign capital. China’s 1992 share of 1.7% (which was also its share in 1978) surged to a peak of 18.3% in 2021 before falling for the first time since 1985 to 16.9% in 2023. While significant for future growth projections, China’s post-pandemic economic woes should not distract us from recognising its extraordinary rise, regaining its lead over Japan’s share of world GDP in 2010 for the first time since 1961.

China’s rapidly increasing international competitiveness is not the only reason that it effectively wiped out 50 years of Japan’s pre-eminence in production, but it is noteworthy that Japan’s decline from its 1995 peak of 17.8% occurred at the same time as China’s take-off accelerated. Perhaps even more strikingly, for the first time since the ‘Great Divergence’ of the nineteenth century,19 China regained its GDP lead over Europe (more specifically the European Union, EU) in 2018. The latter used to be an economic peer competitor of the US, but as Figure 1 shows, it has still not recovered from the 2008-9 global financial and 2010-12 eurozone crises.

Figure 1. National share of world GDP 1960-2023 (in percentages)

Source: S.K. Starrs' calculations from World Bank, 2024

While the concentration of where the world’s production is geographically located is still highly significant for understanding twenty-first-century global capitalism, this does not tell us the full story of the globalisation of ownership and power. For example, when smartphones are assembled in China for export we cannot assume that the bulk of the profit will return to China because those smartphones could be owned by a foreign firm, such as Apple or Samsung Electronics.

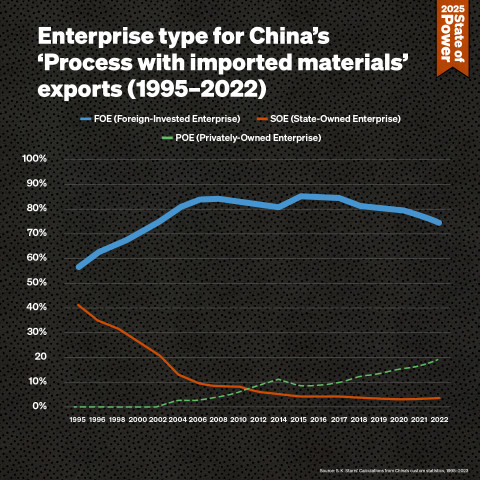

Figure 2 reveals more generally that what China Customs classifies as ‘foreign-invested enterprises’ own three-quarters of China’s most advanced hi-tech goods encompassed in ‘process with imported materials’ exports in 2022, worth $809 billion. These include China’s voluminous electronics exports that involve importing key components, conducting final assembly in China by a foreign firm such as Foxconn, subcontracted by another foreign firm such as Sony, then exporting. While Chinese privately owned enterprises have increased their share of these crucial exports from virtually nil in the 1990s to 20% by 2022 (doubling its share since the dawn of Trump’s post-2018 trade war), this is still much smaller than most would expect from China’s huge national accounts. Hence even if China surpassed Japan in 2010, we still need to investigate who ultimately owns and therefore profits from production in China – and globally.

Figure 2. Enterprise type for China’s ‘Process with Imported Materials’ exports, 1995-202220

Source: S.K. Starrs' calculations, based on China’s Customs Statistics 1995-2023, 2024

To overcome this mismatch of national production with transnational ownership, a useful proxy for measuring what is essentially corporate power is aggregating the national profit-shares of the world’s top transnational corporations (TNCs), encompassing their transnational operations. The accumulation of profit, after all, is the central driving logic of capital. There are several corporate rankings but the best is the annual Forbes Global 2000, the world’s largest 2,000 publicly listed TNCs ranked by a composite index of assets, market value, profit and sales since 2005. Figure 3 shows the 15 sectors in which Chinese corporations have an aggregate top-three profit share in 2024. In the first four sectors, China has the world-leading share. These accord well with China’s state-directed infrastructure-driven growth since its declining exports in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC) as Western imports fell. The remaining sectors represent China’s continued (even if diminished) role as the world’s workshop as well as its emerging domestic consumer market.

Thus, China is second only to the US at the pinnacle of global capitalism with the latter’s top-three presence in 24 of the 25 sectors,21 while Japan’s ten sectors have been pushed to third, trailed by the UK with five and both France and Switzerland with four each. Considering that Chinese TNCs in aggregate did not reach the top three in any sector until 2009 (when China debuted a top-three presence in Banking, Insurance, Real Estate, and Transportation), this is an extraordinarily rapid corporate rise.

Figure 3. Forbes Global 2000 sectors in which China has a top-three profit share in 2024 (in percentages)22

Source: S.K. Starrs' calculations from Forbes Global 2000, 2024 (with research assistance from Quoc Linh Pham and Yizhou Miao)

Following from this, Figure 4 shows the 13 sectors in which the US profit share is dominant, at a level that has remained consistent over the past two decades (the US also dominated in 13, albeit slightly different, sectors in 2005).23 It is in this figure that we really see how national accounts in the age of globalisation can lead one to grossly over- or under-estimate economic power. For example, China has been the world’s largest exporter of electronics since 2004 and yet 20 years later its profit share is ‘only’ 11% (fourth worldwide) while the US share is 43%. This makes intuitive sense once we look at all the ‘Made in China’ labels on US-owned electronics sold by Apple, Amazon, Cisco, Dell, HP, Microsoft, and so on. Even starker, after the Chinese firm Lenovo acquired IBM’s personal computer division in 2005, China became the world’s largest consumer of computers in 2011 and eventually home to the most software developers in the world (over 7 million), yet its profit share is only 6.3% next to the US’ staggering 86%.

China of course has a population more than quadruple that of the US, but the latter’s wealth means that the US dominates in Food, Beverages & Tobacco, and Retail. And while China surpassed the US in Banking in 2009 and has occupied first place ever since (with a peak of 41% in 2021, falling to 31% by 2024), the US, namely Wall Street, dominates Financial Services at 63%. This is significantly higher than the three years before the 2008 Wall Street crash when the US share averaged 48% before tumbling to a 2009 low of 27%. One reason why Wall Street increased its global dominance after its crash is because US ownership of foreign capital subsequently increased. We have elsewhere called this the ‘Americanization of global capital’,24 as US corporate ownership has increased around the world, including of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Finally, US dominance in global media (76%) indicates its ability to ‘manufacture consent’ and shape the agenda around the world – the knowledge structure par excellence.25

Figure 4. All 13 Forbes Global 2000 sectors dominated by the US, 2024 (in percentages)26

Source: S.K. Starrs' calculations from Forbes Global 2000, 2024 (with research assistance from Quoc Linh Pham and Yizhou Miao)

Again, none of this is to deny the extraordinary capitalist rise of China since the 1990s as evidenced in Figures 1 and 3. But we can now see that this has come more at the expense of Japan and Western Europe than of the US. The latter has in fact increased its dominance over the past 20 years in a variety of core sectors despite, or perhaps because of, the rise of China.

Indeed, we are reminded of Henry Luce’s (populariser of the ‘American century’) 1950 call for a more ‘prosperous and integrated Europe’ that would allow US firms to increase their profits but not threaten the US as long as the latter remained dominant.27 A similar logic applies to a more prosperous China, while US firms continue to have access to its labour and consumers (Figure 2 shows that the post-2018 trade and tech wars have so far had only marginal effect on the dominance of foreign firms in Chinese exports). Thus, most of the decisions at the summit of the global production structure on where and what to produce in by far the most sectors are predominantly made in US boardrooms. In sum, in 2024 US-domiciled TNCs led in 19 of the 25 broad sectors of the Forbes Global 2000, while China led in four (and Japan in the remaining two): persistent US dominance of the global production structure is staggering and invisibilised if we only inspect national accounts.

China Will Not Save the World (While it Remains Capitalist)

In Xi’s first term (2012-2017), there seemed to be momentum in fulfilling his grand strategy of re-Orienting Eurasia towards China, if one considered only relational power. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched in 2013 with one (land) belt eventually connecting China with Duisberg on the German Rhine (which then connects to Rotterdam, Europe’s busiest container port) via Russia with high-speed freight trains. The (sea) road follows Zheng He’s early 1400s trade routes through Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, and East Africa. The New Development Bank was established in Shanghai in 2015 and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in Beijing in 2016. The UK government declared a ‘Golden Age’ with China in 2015, and joined the AIIB, as did Italy and other European countries, as well as South Korea, among many others.

China continued breakneck growth, even if peaking at 14% in 2007 still an envious 7.9% in 2012 to 7.0% in 2017. With giant annual export earnings, China launched tens of billions of dollars for industrial policies, namely the ‘Big Fund’ for semiconductors in 2014 and in 2015 ‘Made in China 2025’ (targeting ten sectors). Scores of countries were now exporting more to China than to the US.

With the wind seemingly behind him, Xi spoke to capitalists at the World Economic Forum in January 2017 and admonished those trying to regress the ‘natural outcome’ of ‘economic globalization’ in pointed reference to Trump, and offered China as a more responsible stakeholder of the global trading system. How far China has come since Mao accused Deng Xiaoping of being a ‘capitalist roader’!

But Xi dramatically misjudged the likely response of the world hegemon, the US. He assumed that China could keep ‘transferring’ industry after industry, most of all advanced technology, freely from the US without any blowback. In his first term, President Trump disagreed, initiating a trade then tech war against China. In the process his administration began transforming the nature of globalisation itself, dismissing ‘free trade’ and ushering in a new era of techno-nationalism28 upon which Biden doubled down, in which the ownership of advanced technology is geo-politicised.

The US’s vast structural power was leveraged in a two-pronged approach. First, blockading some of China’s top hi-tech firms (Huawei, SMIC, YMTC) with export controls (including eventually the TNCs of allies, such as the Dutch firm ASML) then entire sectors (advanced chips, Artificial Intelligence (AI), quantum and supercomputing). The US could not do this against Japan in the 1980s nor the Soviet Union during the Cold War because neither was dependent on US technology; they were much more technologically self-sufficient before 1990s globalisation.

Second, the US unleashed an unprecedented stimulus – $5 trillion from March 2020 to March 2021 alone, more than the 1930-40 New Deal– and over $500-billion-worth of industrial policies in the 2022 CHIPS and Science and Inflation Reduction Acts. The US can distribute such unrivalled sums today (and not in decades past) partially because of the rise of China and many other exporters recycling their US dollars back into the US. In this way, China has been the first or second largest (fluctuating with Japan) foreign funder of everything the US does, including US imperialism against China. No other empire has ever constructed a financial system in which the chief geopolitical rival is structurally bound to finance its own containment.

Relatedly, the most devastating US comparative advantage is its extraordinary capacity for mass death and destruction (whether directly or via proxies) while professing the noblest of intentions and having so many people believe it (especially those who still uncritically ingest establishment news).

Without having space to evidence planning,29 fast-forward to the beginning of 2025: Western allies (the G7, NATO) are now convinced that China is a ‘systemic rival’, China’s BRI route through Russia is cut off by US-led sanctions essentially decoupling Russia from Western capitalism. Israel is on a regional rampage partially to clear the way for the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) announced at the New Delhi G20 meeting in September 2023,30 checking China’s sea road and Middle East influence in general (in times of war, China has no military capacity to compete with US influence in the region, and as the Assad government has fallen in Syria, Russia’s influence is diminished while also being distracted in its war on Ukraine). The EU and UK’s ‘Golden Age’ with China less than a decade ago is now a molten mess.

Irrespective of this turn of events, understanding structural over relational power is more fruitful for analysing longer-term trends in the geopolitics of capital and this essay offers a new methodology to do so, revealing staggering US dominance across multiple structures.

What would China have to do to ‘save the world’ from US imperialism and capitalism itself driving exploitation, oppression, and industrial ecocide? Sign mutual defence treaties with as many around the world as possible (since 1949 China has preferred to remain unentangled), assist the industrialisation of the Global South including transferring technology and manufacturing (not just infrastructure development and/or de-industrialising resource extraction), move towards de-dollarisation by establishing an alternative international currency not corrupted by national interest (i.e. not the RMB), rapidly increase social welfare at home and abroad to boost living standards, drastically reduce fossil-fuel burning and help others do the same, to name a few.

But as long as China remains capitalist it will have no incentive to fundamentally transform global capitalism, especially when its hegemon is willing to defend its power by provoking World War III. So, Chinese workers must first initiate another socialist revolution to remove capitalism from China, perhaps in collaboration with revolutions around the world to remove the logic of endless capital accumulation via class exploitation and oppression – most of all in the US, to unshackle the global grip of its ruling class. This is of course a tall order. But if there is one country that embodies Marx’s dictum ‘All that is Solid Melts into Air’ it is China since 1911, undergoing multiple revolutions and counter-revolutions: nightmares have become Chinese dreams before.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: