De-risking and non-profits: how do you solve a problem that no-one wants to take responsibility for?

Topics

Decisive action should be taken by the G20 to assess the impact, legitimacy and effectiveness of the whole system of international rules designed to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

Wikimedia

This article first appeared on Open Democracy

‘De-risking’ is shorthand for business practices designed to make something – an activity or an investment portfolio, for example – less risky and, crucially, less likely to involve a financial loss.

Over the past few years ‘de-risking’ has taken on a more specific meaning within the banking and financial services sector where it is used to describe the practice of financial institutions exiting relationships with and closing the accounts of clients considered ‘high risk’.

This kind of de-risking effects different organisations in different ways and its impact varies geographically; but correspondent banking relationships, where a large financial institution provides international financial services to a smaller one, appear to have been hit hardest.

There are lots of concerns about de-risking. Most money transfer organisations, for example, are wholly dependent on correspondent banking relationships (hereafter: CBRs), so the termination of those relationships has a direct impact on the flow of remittances. More broadly, because the wider banking sector in less developed countries has been heavily dependent on CBRs with established multinational banks, de-risking is seen to reduce the ability of those countries to participate in the global economy, threatening global trade and economic development.

There is now a growing body of evidence showing that the non-profit sector may have been as heavily impacted by de-risking as CBRs (see for example here, here, and here). But it is concerns about the latter that have seen de-risking placed firmly on the agenda of a growing number of intergovernmental organisations (IGOs), from the IMF to the G20, which will for the third year running note concerns about de-risking when it meets this week.

Why is de-risking happening?

Analysts have put forward various explanations for de-risking but almost all agree that international rules designed to combat money laundering and terrorist financing are the most significant.

These ‘AML-CFT’ rules require financial service providers to conduct extensive ‘due diligence’ on their customers and transactions to ensure that they do not facilitate such criminal activity. They must also ensure that they do not inadvertently breach any of the national and international sanctions regimes or financial ‘blacklists’ that now span the globe in their hundreds.

AML-CFT compliance is subject to intense scrutiny by regulators and bank examiners, and is underscored by substantial criminal or civil penalties for failures or lapses, and the reputational damage this brings.

The rising cost of compliance with these requirements, which in practice require financial institutions to profile all their customers and subject them to ongoing surveillance, coupled with the relatively small profits that may be gained from correspondent banking relationships, is widely seen as the key driver of de-risking.

Conversely, high net worth clients, who may also pose a high risk in the context of stricter AML/CFT rules, do not appear to appear to be adversely affected by de-risking.

De-risking and non-profits

The research suggests that it is international non-profit organizations (NPOs) working in or around conflict zones and the more ‘political’ (or politicised) causes within the non-profit sector that have been hardest hit by de-risking.

Just as the termination of correspondent banking relationships is seen to undermine economic development, the de-risking of NPOs jeopardises the ability of human rights activists, humanitarian organisations and many others to implement their mandates. This undermines the capacity of civil society to hold governments to account, provide much-needed aid and relief, and to advocate for political and social change. As with CBRs, the lack of profit that banks make from the non-profits is believed to be among the key drivers behind the de-risking of NPOs, but other factors such as the banks’ perception of the sector and the de-legitimisation of specific organisations and activities are also relevant. International bodies with a counter-terrorism mandate have asserted that NPOs were “particularly vulnerable” to terrorist financing and although they have now rowed back from this position, the proverbial mud has stuck.

Kafka at the bank

We have spent the last few years meeting with non-profits affected by de-risking all over the world. Here is a sample of the kinds of stories we are by now all too familiar with.

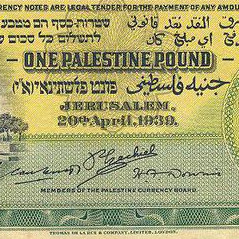

A small campaign group working nationally to raise awareness about the plight of Palestinians is staffed mostly by volunteers and funded by the monthly donations of its members. It has had the same bank account for nigh on 20 years and does not fund any political activities in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Out of the blue it receives a letter from its bank saying that it has two months to find an alternative financial service provider; its accounts are to be closed because it no longer falls within the “risk appetite” of the bank.

The bank refuses to negotiate and offers no further explanation. Other commercial banks refuse to take on the organisation. Instead of campaigning for Palestine, the organisation is now embroiled in a legal and administrative nightmare. Although it is ultimately able to open an account with a not for profit bank, it has by then lost a sizeable chunk of its income, because many of its supporters do not amend their standing order mandates.

Consider also the large international relief and development organisation with programmes all over the world and an annual budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Over the past two years, transferring money to its offices and implementing partners around the world has become increasingly onerous. Transfers are delayed for weeks, additional documentation of internal vetting and due diligence procedures are more and more onerous.

It is by now impossible to get funds into some of the countries where the organisation’s activities are most urgently needed, so they send it to a neighbouring state and use local (informal) money changers to get the funds to their final destination. Sometimes transactions are executed but the recipient bank refuses to release the funds to the beneficiary. Local police have intimidated the partners, and lawyers have been instructed to secure the return of the funds. Eventually the bank requests the organisation to sign a document effectively indemnifying it against any AML-CFT fines it might incur as a result of providing financial services to the humanitarians. They part company.

These are examples of how de-risking is affecting long-established organisations based in western countries. Imagine what is happening to groups in less democratic regions, where de-risking and financial surveillance is playing out in much more politicised and repressive ways.

We have encountered non-profits as diverse as reproductive health clinics, progressive theologians, medical researchers, environmental campaigners and animal rights groups from all corners of the world – all with similar tales to tell. The biggest irony of these sorry stories is that rules that were designed to allow law enforcement to “follow the money” now appear to be pushing that money into unregulated channels, as frustrated organisations are left with no other option to dispense their funds.

A problem of perspective: through the looking glasses

As noted above, more and more IGOs are taking an interest in de-risking, though relatively few are particularly concerned about the impact on non-profits. The most powerful actors, like the G20, view de-risking primarily as a “financial stability” issue that – because of the impacts on correspondent banking, the arteries of the global financial system – threatens to derail economic development and trade financing.

Others, like the World Bank, have widened the frame to encompass financial integrity and financial inclusion, reminding us that the banks are supposed to be good global citizens providing a public service, not simply protecting their profit margins at any cost.

It is important to stress here that not all banks are behaving the same; a minority at least are clearly doing their best to help non-profits deal with the brave new world of hyper-transparency and excessive risk aversion. Nevertheless the banking associations, quite understandably, prefer to point toward to the reality of the AML-CFT frameworks and the huge fines they face for getting things wrong.

From the perspective of a global compliance industry already worth $80 billion annually and straddled by the much-hyped “fintech” and now “regtech” sectors, the disruption caused by de-risking is little more than an opportunity for “disruptive” innovation.

Meanwhile, the architects of the AML-CFT framework deny that the problems described are caused by their regulations, asserting instead that the banks are misinterpreting and/or misapplying the requirements, all the while lamenting the disappearance of clean money into “shadow banking” channels.

Despite “financial inclusion” being repeatedly referenced as a key enabler of various Sustainable Development Goals, the mechanisms actually designed to ensure financial inclusion, like the G20’s global partnership, are yet to take a position on de-risking. Several of the UN Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteurs have called for non-profit-friendly reform of the AML-CFT regimes and suggested that arbitrary decision-making by the banks risks manifest breaches of non-discrimination laws, but none of the stakeholders want to talk about public law remedies or mechanisms for redress.

Finally, the vast majority of non-profits we speak to see the problems they are newly encountering with their banks squarely within the worldwide trend that is now widely known as the “shrinking space” for civil society. Restrictions on foreign funding and political activities, over-regulation via national non-profit laws, increased attention from law enforcement – for already squeezed civil society organisations in many parts of the world, it’s as if the banks are simply sticking the boot in.

Elephants in the room

The wider problems facing non-profit organisations are among several fundamental issues that no-one with a shred of responsibility for de-risking wants to talk about. Also off-the-table is the democratic legitimacy of a global system for countering terrorist financing that was quickly drawn-up by US officials in the wake of 9/11 and railroaded through the intergovernmental decision-making system in just six weeks.

So too are questions as to the ultimate effectiveness of a system whose “negative externalities” are piling-up, but whose impact in terms of actually stopping the flow of funds to terrorist groups and their supporters is at best disputed and at worst rejected outright.

Neither is there any current appetite for critical reflection on the implications of effectively turning our banks into police stations and having them, or outsourced compliance services, stockpile data on individuals and organisations, which can in many states be accessed at will by national “Financial Intelligence Units”.

Because these rules apply globally, including in countries where there are no meaningful “checks-and-balances” or separation of powers – never mind data protection – data collected under the auspices of “due diligence” is now being used to repress activists and non-profits from Hungary to India, Russia to Sudan, Egypt to Mexico. Yet the international community has failed to provide a forum in which these trends and their consequences can be properly discussed.

Ownership and accountability

It is not tenable to leave these issues to the banks and their customers to sort out. By avoiding the difficult conversations we will only sustain an environment in which powerful states and IGOs can evade responsibility for the situation they have created.

As long as there is no ownership of these problems, there will be no mandate to develop the comprehensive solutions that are now clearly required. The longer this situation persists, the more deeply embedded in the intergovernmental order, national law and banking practice the core problems become.

In seeking to find work-arounds rather than reforms, non-profits are forced to internalise the problem and put pragmatism before principle. While this is perfectly understandable given the urgent need to access financial services, we are concerned that the rush to find practical solutions for certain types of organisations, sectors or regions actually risks reinforcing or compounding the problems facing others.

Further harmonisation and standard-setting; kite marks, self-certification and better risk management practices; new technologies and dedicated non-profit compliance services may all have a part to play in arresting the de-risking of non-profits, but all have consequences for the sector that require careful reflection from the outset.

Bottom-up approaches tailored to specific countries and regions, using a mix of policy, financial and legal solutions, may be more appropriate than the top-down decision-making that has created these problems. But they are no substitute for the decisive action that could and should be taken by the G20 to assess the impact, legitimacy and effectiveness of the AML-CFT system as a whole, paving the way for the corrective action that the situation demands.