Dependency by design: How the JET-IP structures South Africa’s energy future

Regions

As South Africa hosts the G20 summit, it must learn from the failures of the ‘Just Energy Transition Investment Plan’ that has undermined its economic and energy sovereignty. A just transition in the majority world requires sovereign, sustainable and people-centred economic policies.

Meraj Chhaya/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

The calamitous consequences of global dependence on fossil fuels is indisputable yet governments continue to subsidise the right to inflict catastrophic damage. Researchers estimate that “[b]etween January 2020 and August 2022, the 38 largest economies and 8 multilateral development banks…committed $515 billion in new financing to fossil fuel–intensive sectors, compared to $488 billion to clean energy sectors[.]” It is with this backdrop that the South African government is set to host the first G20 summit in Africa at the end of November.

Many are looking to the South African government to bring decisive leadership on issues of debt, global critical mineral supply chains, and financing for a just energy transition. However, if the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP) partnership between South Africa and the International Partners Group (IPG) — initially comprising France, Germany, the UK, the US, and the EU — is anything to go by, the summit discussions will leave workers and communities across the Global South in an even worse position.

The Just Energy Transition Partnership was announced in 2021 by President Ramaphosa as part of South Africa’s desire to “…accelerate the just transition and the decarbonisation of the electricity system, and to develop new economic opportunities such as green hydrogen and electric vehicles amongst other interventions to support South Africa’s shift towards a low carbon future,”

Putting aside that the European Union, a member of the IPG, increased its coal imports from South Africa by 40% in 2022, the South African government identified that its aim to decarbonise through the JET-IP from 2023-2027 would cost $98.7 billion. It has received a funding commitment from the IPG, which Denmark and Netherlands also later joined, of $13.8 billion. This figure dropped to $12.8 billion after Donald Trump, in another ‘climate change is not real’ delusion, withdrew pledged US funding at the start of 2025.

Economic Dependency and Supply Chain Control

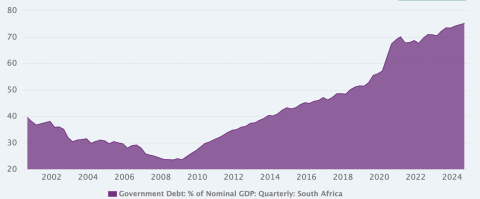

South Africa’s JETP investment plan (JET-IP) describes a just transition as one that “…builds the resilience of the economy and people through affordable, decentralised, diversely owned renewable systems[.]” But the processes and finances of the JET-IP do not tell the same story. By 2024, only 4% of JET-IP financing was in the form of grants, meaning that most of the money South Africa receives is structured as loans. More debt for a country that is already drowning in it. In October 2022, the month before the JET-IP was announced, South Africa’s debt totalled about 70% of its nominal GDP, continuing an almost 20 year upward trend.

Ceicdata.com

In a 2024 survey of the JET-IP grant financing, the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies at Wits University found that 76% of the grant funds had been given to foreign entities to implement aspects of the JET-IP. More than one-third of the total grant financing was given to the German development agency and bank. Similar patterns were found for the grant funds received from the US, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Grant dollars were being used to strengthen donor country institutions instead of South African institutions. One German official argued that, even if South Africans are not the implementers, this was fine since they benefited from the work done by foreign entities. But Africa has learned what happens when you are a ‘beneficiary’ and not the one who controls the money and how it is used. You lose control of the political and economic development path of your country. This case is no different.

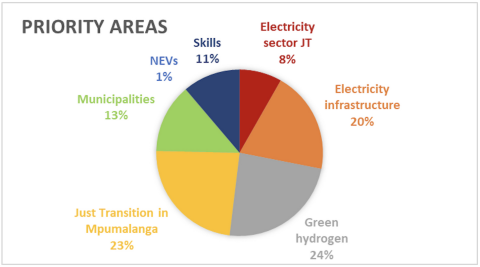

A range of priority areas are identified for grant dollar allocation in the JET-IP.

Lehmann-Grube et al/Wits University (2024)

Electricity infrastructure is allotted 20% but almost none of those funds have been used for that purpose. Instead the money has been spent “…on a mix of technical assistance, project feasibility studies, scenario projections and capacity building.” That leaves longer-term structural interventions that South Africa is in desperate need of, like electric grids and renewable infrastructure, to be financed by loans. This type of infrastructural financing often means that infrastructure is either fully owned or partially owned by foreign private companies or foreign governments.

Further consolidating the path of dependency, the JET-IP was only opened for input from the South African public after half the grant dollars had been apportioned. Meanwhile the JET-IP was developed under the guidance of the IPG group. As if this imbalance of power between the South African people and foreign interests was not problematic enough, only 0.4% of the grant dollars had been allocated to civil society organisations and worker’s unions as of 2024. With no allocation “…provided for care for workers in affected value chains (as stipulated in the [JET-IP]), nor social protection more broadly.” While some money has gone to skills training, a key priority for labour unions, even that is not without its limitations. One of the costs allocated to the skills category included paying an employee of the British High Commission to work with the Presidential Climate Commission.

Using the need for climate action as a front for policies that increase indebtedness and create an even more dependent South African economy is not part of a transformative solution to structural environmental and economic crises. Decarbonisation or renewable energy investments, technologies and infrastructure that people still do not have access to or control over can also not be considered a just transition strategy. Sovereign, sustainable and people-centred economic development is not at odds with climate action; it is integral to its success.

The logic undergirding African economies must stop serving the accumulation of capital and the centralization of power in the hands of a few if we want to get Africa out of the debt and dependency starvation cycle. The just transition is not just a technical transition but also an ideological one. There is nothing inevitable about predatorial extractive economic systems. An economy is a set of decisions. Should we decide to make a different set of decisions, we can advance sovereign, sustainable, and people-centred economic development that is consistent with pro-worker and pro-environment agendas.