Power and politics through keywords in everyday life

Topics

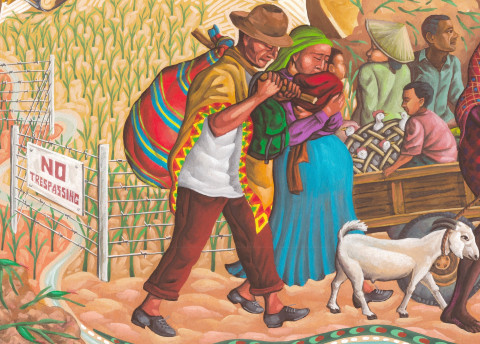

What a keyword means to you often depends on which side of the fence you stand. The term ‘land tenure security’ can be protecting poor peasants, but it could also mean legitimizing a land grab by a corporation and legalizing the dispossession of the displaced villagers. Power and politics do operate through keywords in everyday life.

© Boy Dominguez

“No trespassing” is one of the most ubiquitous keywords we see in the world. It is deployed in order to claim and protect the ownership of something, often land, by someone. It is a keyword that excludes. Keywords are relational. They are embedded in power relations. They are, thus, political. Everyone with a land claim can use the term “no trespassing”, but who has the ability to enforce it is another story. Keywords neither self-interpret nor self-implement. Activation of keywords unfolds in the actual dynamics of social relations among groups and classes in society. In his This Land Is Your Land, Woody Guthrie sang:

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing”.

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

The meanings of keywords constantly evolve. As Raymond Williams in his Introduction to his book, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, said: it is the subsequent variation in the meaning of keyword that is often more interesting than its original meaning. It is thus difficult to attribute final meanings to keywords. Moreover, when taken as a stand-alone term, a keyword can easily be interpreted in ways that are different from its original signification. The structural, institutional and political conditions of societies play a role in crafting keywords and giving them meanings in particular historical conjuncture.

There are some interesting patterns in terms of clustering meanings and how they are contested and transformed over time. We offer partial and preliminary ways of clustering such changes in the context of land and agrarian transformations.

Same keywords, different meanings. Giving a keynote in an international conference in 2017, Henry Bernstein said that there are no peasants in the world today. Paul Nicholson, the first general coordinator of La Via Campesina (LVC), stood up and shouted: Somos! We are! We exist! As explained by Marc Edelman, the term ‘peasant’ is used to mean different social categories: backward people from the countryside who are uneducated and live in drudgery; social category that existed only in pre-capitalist world and later had been differentiated into small-scale capitalist farmers, petty commodity producers and landless wage labourers; a broad category that includes landless labourer to small and medium-size farmers who work the land to construct a livelihood and are key social group in today’s world.

It matters for what purpose one uses what keyword: academics critically examine social dynamics and capitalism, while activists imagine and construct actual alternatives. For Bernstein, peasants do not exist; for Nicholson, peasants exist. The French farmer and current general coordinator of LVC, Morgan Ody, said: “Peasants are humiliated for being peasants and for having the culture of being peasants… When you are humiliated, you need to reclaim the word to say, actually, yes, I am a peasant and it’s something beautiful.” Edelman’s new book, Peasant Politics of the Twenty-First Century seems to take the position that peasants exist, and brings the matter back to academic conversations. Bernstein, Nicholson, Ody and Edelman advance important contributions to thinking about anti-capitalist struggles, if we follow Erik Olin Wright who reminded us that to be anti-capitalist in the twenty-first century “we need a way of assessing not just what is wrong with capitalism, but what is desirable about alternatives.”

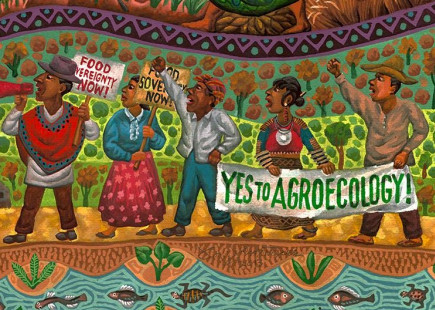

© Boy Dominguez

Same keywords, opposite meanings. In the classical meaning of ‘land reform’ for the most part of the 20th century, it means redistributing land from owners of big capital to landless and land-poor impoverished rural working people. There is a clear class dimension in the direction of change effected by land reform: from the rich to the poor. Since the neoliberal era from the 1980s onwards, mainstream land reform has meant reallocating land from what is assumed (quite problematically) to be economically inefficient impoverished rural working people, to the owners of big capital in the name of economic efficiency and the capitalist dream of limitless economic growth. This is the justification for declaring expropriationary redistributive land reforms, and replacing them with the so-called market-assisted land reform and land tenure formalization projects by the World Bank. Land tenure security in the 20th century almost always meant improving and protecting the tenure security of the working poor; today, it is widely used to protect existing private property systems often benefitting the rich and the powerful.

Different keywords, one meaning. Different keywords are interchanged and conflated to vaguely refer to the same social phenomenon, leading to a confusing understanding of realities. The global land rush that was reported around 2008 has since then generated different keywords to refer to the phenomenon: large-scale land acquisition, large-scale land investments, land grabs, land deals, land enclosure, land boom, and land rush. The conflation of these keywords has led to less clarity about social realities and how to address them. There are also keywords with different, yet overlapping, meanings. When tackled together, these keywords can become complicated, or enriched, such as in Ian Scoones’ discussion of peasants and pastoralists or his discussion of the ideas of controlled planning and uncertainty, and Jennifer Clapp’s exploration of food security and food sovereignty.

Catch-all keywords. There are keywords whose usage is stretched to cover social realities that may not logically and actually fit. The term ‘agrarian reform’ is often used as a catch-all term to cover all reforms in land politics that supposedly favour the marginalized classes and groups in the countryside. But while it gains traction and political support from some groups of the rural working class, it generates resentment from others. To many Indigenous peoples, agrarian reform was the state policy that, in wanting to avoid expropriating politically powerful landlords, decided to instead distribute Indigenous lands to land-hungry peasants. For peasants, the term ‘agrarian reform’ means inclusion and possession; for many Indigenous and pastoralist communities, it means expulsion and dispossession. This reminds us to always take keywords not a stand-alone term, but always in relation to others.

Negative keywords. Generally, there is nothing inherently good or bad in keywords as their interpretation depends on actual balance of social forces for or against particular meanings. But there are some words in which the long-standing dominant meanings are associated with particular tradition. The term ‘social justice’ tends to always be in favour of the exploited and the oppressed. But there are keywords imbued with a negative connotation. The term ‘agrarian populism’ that was popularized in the late 19th century Russian left, meant romantically celebrating undifferentiated communities, class-blind, and naively believing in the role of peasants in building a positive future outside capitalism. Today, agrarian populism is a term used in a derogatory way by a section of Marxist academics to ridicule and downplay the importance of one of the world’s most potent and best organized anti-capitalist social movements, the broad agrarian movements on the same basis used in the late 19th century Russia. The criticism is persistent even when in actual reality many of these social movements and their supporters have foundational ideological moorings rooted in Marxism and class politics.

Emerging keywords. As structural, institutional and political transformations unfold worldwide, and the understandings of these are altered, old keywords acquire different meanings, and new keywords emerge. By examining the fragmentation of classes in current global capitalism, Bernstein has developed and advanced the concept of ‘classes of labour’. Challenging the neoclassical economics idea of limitless economic growth, ecological economists advanced the concept of ‘degrowth’. Some are adaptation of classic concepts to new realities, such as social justice in the era of climate change: climate justice. It is in this context that several relevant concepts have emerged: green grabbing, land scarcity, food sovereignty, green colonialism, plantationocene, climate security, investment, etc. The Journal of Peasant Studies (JPS) has a section on Key Concepts, and has published keywords including: agro-extractivism, the second contradiction of capitalism, and anticipatory ruination, providing a useful guide in navigating the emerging field of Critical Agrarian Studies.

How the rich and the powerful put meanings on keywords and make them hegemonic happens in the corridors of power and academia. The exploited and the oppressed challenge this by advancing competing meanings to the same keywords. The hegemonic-counterhegemonic keyword-making and meaning-giving are fiercely contested political processes – in rural villages, university classrooms, ministry meeting rooms, corporate boardrooms, intergovernmental reports, and in international conferences.

Incidentally, there were and are major international events in which the politics of land were and will be debated and discussed – but from very different perspectives within and across these events: the annual World Bank international land conference in Washington DC, the LDPI global land grabbing conference in March 2024, the Global Land Forum in June 2025 in Bogota, Nyeleni2025 world assembly on food sovereignty in Sri Lanka in September 2025, the Land, Life and Society international conference at PLAAS in Cape Town in October 2025, and the International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD+20) in Cartagena, Colombia in February 2026. It is important to take a close look at these events and reflect on the politics of keywords used by different individuals and groups. During the 20th century, the term ‘land tenure security’ had a deeply subversive meaning against the status quo marked by land monopoly and a call for redistributing lands democratically. Nowadays, the term ‘land tenure security’ is deployed to disqualify land redistribution from the official agenda, and its meaning flipped: to mean ratifying the status quo of deeply undemocratic distribution of land access and ownership. Many in these aforementioned fora are expected to declare the need to promote ‘land tenure security’, just as the numerous reports of the IPCC do. However, without specifying which land, what tenure, and whose security based on class and interlocking axes of social differences (gender, generation, race, ethnicity) this entails, and who gains and who loses, even well-intentioned narratives may inadvertently be used to promote the interest of big capital, rather than of the rural working class.

The issue of the politics of land remains important and urgent, and we see a body of old and new keywords of land politics emerging, with competing, conflicting, parallel, complementary meanings. How do we make sense of this, and how do we navigate this complex politics? It is in this context that we have published a book on keywords – Essential Concepts of Land Politics – in which we compiled, discuss, and explain the key concepts in land politics.

Boy Dominguez and John B. Tan – ©

This book takes a broad view on land, across the rural and urban corridor, and advocates for a holistic view of the politics of land, as an aggregation of land and global social life, that is, the politics of food, climate, labour, citizenship, and geopolitics. We have curated a wide-ranging list of 67 key terms most commonly used in the study of land politics, with each entry mapping out an important concept or idea and illustrating how it relates more broadly across the growing field of critical agrarian, environmental and food studies. The key concepts in this book are therefore not discussed in a random way but rather framed from the field’s critical perspectives and scholar-activist tradition, which means taking the side of the exploited and the oppressed. With further reading recommendations included alongside the entries, this book will be useful to students, policy practitioners, and political activists. There is a 25% discount when ordering the book using the code: ECLP25.