Right to Repair and Circular Economy Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Topics

This conversation examines the connections between recycling, material reduction, and extractivism, focusing on nickel production in Indonesia. It explores how policies reducing extraction could benefit communities, the limits of recycling, and how reducing material use in Northern economies could alleviate extraction pressure. It also discusses justice in circular economy visions.

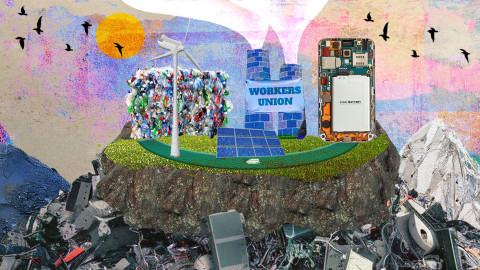

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Defining critical minerals

Katie: Michael could I ask you to start by contextualizing this term ‘critical minerals' or 'transition minerals', and what is meant by it by different actors?

Michael Reckordt: The term 'critical minerals' is a political term. Critical minerals deposits can be used to put pressure on other countries. The term was evoked in Europe around 2010, when China changed their mining policies. They were facing protests around the social and environmental impacts of rare earth mining, and also in a geo-strategic conflict with Japan over some islands, so they suspended their exports of rare earth elements. Within a neoliberal trade framing and the WTO, you cannot say ‘hey, sorry Japan, you don’t get the material anymore’, so that initiated the contemporary issues with raw materials. ‘Critical raw materials’ are critical because, on the one hand, they are located in countries that are not our strongest geopolitical allies, and on the other hand we need them for our industry. The critical raw materials lists from the US, Europe, Germany, Japan and other countries, therefore, differ because it depends on the materials these countries or their partners need urgently for their industries.

The most recent step for the EU has been the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), developed after the pandemic, when exports from China were blocked for several weeks; and the Russian attack on Ukraine. Germany depends heavily on Russia for fossil fuels and cheap energy prices, but also for aluminium, nickel, platinum group metals and others. Currently, there is very little mining, refining or smelting in Europe, and the CRMA is the first regulation in clear support of more.

Katie: Thank you, a great overview. Pius, from the Indonesian perspective, could you tell us about the main issues you are confronting around critical minerals?

Pius: In Indonesia, extractivism of transition minerals, especially nickel, is expanding very fast in the last few years. It creates social and environmental problems. Coal-powered plants [for refining and smelting] create air pollution for villagers, who previously lived in pristine areas with clean air, but now, activists from Jakarta who visit the nickel industrial areas get sick from the bad air quality. Communities and workers are constantly exposed, and it is especially serious for children and elders. These communities have contributed very little to the climate crisis but are now the most impacted by proposed solutions. It is an injustice especially in the eastern part of Indonesia, in central Sulawesi, and North Maluku, because nickel is concentrated in these islands.

Workers also suffer from low safety standards. There are fatal incidents. Burns or accidents with heavy duty vehicles are common. So, a just transition is not just about job security for workers in the fossil fuel industry, but also the labour rights and safety of workers in these new industries.

Indigenous communities that live in the very biodiverse ecosystems [where nickel is being extracted] also need to be taken into account, so Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) needs to be upheld. Germany has signed on to ILO 169 Convention [the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ Convention]. So, we hope Germany will take a role in making its supply chains protect indigenous people's rights and communal lands.

Addressing Just Transitions

Katie: Could you tell us a bit about how your organizations or movements you work with are addressing some of these issues for a just transition?

Michael: As the German network AK Rohstoffe and PowerShift we started to work on a ‘Raw Materials Transition’. We have to be aware that we need metals and minerals, in our societies and in our daily life. We cannot phase out like with the fossil fuels. This is true for the Global South, Global North or elsewhere.

So, the first pillar of our Raw Material Transition is: we have to improve the situation in mining areas, to ensure that human rights and workers’ rights are not violated, and that environmental damage is minimized. Mining always affects the environment, and the question of re-naturalizing in the end of mining life is a huge issue. In Peru or in the Philippines companies often go away without addressing destruction and deforestation, but we have to deal with it, also increasingly in Europe.

Then we have the second pillar: We have to reduce our consumption dramatically in the Global North, because the burden we are putting on the Global South and other resource-rich countries is immense, and unjust on a global scale. We have to identify where we can reduce our material consumption. We have to improve the use of metals, be much smarter and discuss whether we really need some products or not.

Katie: Very important pillars. Is demand reduction also being discussed in Indonesia?

Pius: Part of our campaign is also regarding demand reduction. We need to reduce the demand in order to fully supply [nickel] from renewable energy.

This is also the interest of the national government, to be competitive in the international market. The EU’s CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) means it will be problematic later if the nickel products in Indonesia are processed by fossil fuels. So to be accepted in the global market, we need to move to decarbonizing nickel production. Right now, nickel processing is powered by coal power plants in most places. This needs to be shifted, and the level of production needs to be matched with the capacity of green renewable energy, which needs investment. Wind farms or solar photovoltaics need to be feasible, and investment needs to consider the amount and the duration of demand for that energy. If levels of extraction remain very high, some data mentions that Indonesian nickel may be used up in 20 years. This would mean renewable energy infrastructure would become a stranded asset because reserves would diminish and the demand for energy to process it would fall. So we want to avoid this.

We are advocating for a low-carbon economy that needs critical minerals, transition minerals, but we want to move the transition in a just and good way, not create new problems.

Indonesia's export ban

Katie: Could you tell us about Indonesia’s ban on the export of unprocessed nickel? How do you see its impact on local development and possibilities for a just transition in Indonesia?

Pius: Indonesia banned export of [unprocessed] nickel since 2014 and the export of ore has decreased to near zero. But processed nickel products, such as nickel pig iron, have been increasing, because the government supported companies to build industrial parks. If this was done in a better way, it could give more benefit in terms of local economic development. Older nickel smelters in Indonesia, such as those in south Sulawesi, had investments from Canada since the 1970s. The government gets more royalties [from these older smelters] because instead of being based on the mineral ore value, the royalty is based on the value of processed nickel. So this makes an economic contribution to the government, to fund social sufficiency for citizens.

But since the ban in 2014, the royalty is based on the ore value for the new nickel smelters. The processed product is still exported but does not provide the same income to the local and national government, because of this tax incentive or tax holiday. The local government will only get maybe 5% of all total GDP created by this industry.

Based on government data, the number of people living below the poverty line is higher in the industrial nickel districts, compared to other districts in the same province without nickel industries, such as central Sulawesi and North Maluku. So the benefits from these industries need to be improved to make it more equitable for communities living near these industries.

Katie: That is very interesting and surprising to me to hear that even though the nickel is being processed before export, the royalties are being paid based on the raw ore. Are there groups working on changing that, or trying to ensure that more of the benefits go to local communities?

Pius: This is already a concern for the locals who know about this scheme, but the NGOs are mostly working on the environmental impacts and on decarbonizing industries because almost all smelters are using coal power plants. But the tax holiday needs to be ended in order to give more benefit to the communities.

Refuse, rethink and reduce

Katie: A really important point. Michael, you mentioned 'circular economy' in the context of the EU. Could you tell us what that means, and if there are different definitions?

Michael: The easiest way to make it clear is through the 10 Rs. For us, the first three steps towards a circular economy are: refuse, rethink and reduce. Do we need these critical raw materials? Do we need the products and functions these products give us? Are there better ways to have this function? Can we reduce our consumption?

We often talk only about resource efficiency, meaning improving the resource-use of a single product. But considering rebound effects [where increasing efficiency does not decrease material use because people consume more] means this could mean even more raw material use. So ‘refuse, rethink and reduce’ is the first step. And it is completely lacking in the Critical Raw Materials Act.

The second part of the 10 Rs: is reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture and repurpose. This is wonderfully designed in the graphic by the Austrian Circular Economy Strategy. This means: Can we repair a product? Do we have a right to repair? Can we replace the battery in a cell phone? Can we reuse it? It was a huge issue in the [EU] Battery Directive. After the first life of a car battery, can we use it as energy storage? Or are there other uses? Can we use the cells in a pedelec [a bicycle that generates power when the cyclist is pedalling] or anything else?

Then, we have refurbish. Can we renew it? Very often, for smartphones, the software is a big issue. Can we have new software and use smartphones for another year or five years? Re-manufacture: can we have parts reused in the future? And repurpose, do we have another use for the product?

The last two R’s are recycle and recover, getting the material back in the loop. This is where the EU has a target in the Critical Raw Materials Act – to recycle 25% of all material used. All this is a small part of what a circular economy or circular society should be.

Katie: Pius, could I ask, how do these terms resonate in Indonesia at? Is there discussion around demand reduction or planning for recycling of nickel?

Pius: We see that we need to limit [nickel] production, so that it can be powered by renewable energy and coal-powered plants can be retired, and to avoid massive deforestation, unsustainable practices and even floods.

Regarding recycling, right now, global nickel prices are low. Certain countries are pausing their production because of cheap and abundant products from Indonesia, which is not sustainable for Indonesia’s renewable energy infrastructure. Maybe we need investments in renewable energy in order for it to be feasible for another 30 or 40 years.

Based on the data from the International Energy Agency, the level of recycling for nickel is very low and expected to remain low until 2040.This is different for aluminium, which is already almost 50%. This means there will be a need for continuous mining, because the level of recycling is so low. We need to diversify battery production [in Indonesia] so that it doesn't rely solely on nickel. We need to think about these two concerns on the macro level.

Katie: It sounds like recycling is only a very partial answer in the short term. Michael, could you say a bit about the power structures that keep in place a system that doesn’t think about reducing, rethinking, repairing, repurposing, etc?

Michael: Well, the easy answer is our whole economy. The first thing is the price. The main reason we waste so many raw materials is because we are bad at collecting and sorting the products containing them. The issue is that the value in these production steps is very low. It is often hard, manual work. It is often more expensive than having primary material. So it’s cheaper to mine than to recycle or have a circular economy.

Secondly, metals are often cheaper than some substitutes. In housing or office construction, we could use wooden constructions to save steel and aluminium for windows, but metals are still cheaper.

Our societies are not prepared to think about refuse, rethink, reduce…We see advertisements to buy this or that. We buy things because they look good or are very practical. But this practicality or nice design can be counter-productive for recycling. For example, if you cannot remove the battery, you have to throw away the whole smartphone.

As PowerShift, our investigation found that in Germany, 32% of all metals are going to the mobility sector. This includes some bikes, buses and public transport, but these are a minority. It is mostly private cars. So, this is one of the main leverage points we see in Germany. We have also done some research on minerals in the housing sector, but this is a much more challenging sector to address while we are also facing higher rents and lack of housing. So, mobility is a key issue. However, the automobile sector is super hard to address. In Germany, it is probably the most powerful sector, and connected to the fossil fuel industry. It is also connected strongly to labour unions, and the automobile sector in Germany has well-organized, well-paid generally safe jobs. But the German car industry is very special because we produce the big two-something tonne cars, while Italy and France are producing much smaller cars. So, the segment is hard to address. Strategic decisions had to be made 20 years ago around decarbonization of the transport and automobile sector. We are not frontrunners. We thought we could make the combustion engine be less CO2 intensive, like a miracle, but sadly we failed.

There are also challenges in this sector as part of a Just Transition. As PowerShift, we talk to trade unions and ask: where do we agree? Of course, if we say 'we need fewer, smaller and lighter cars', we still have a conflict, but if we say 'let's talk about circular economy', they are open, because they see the human rights and environmental impacts of mining, and are open to think about making production smarter.

Yukari: Great, thanks for that Michael. Pius, your organization in Indonesia also works on public transport and the mobility sector for reducing material demand. Could you tell us about that? What movements, organizations or trade unions are you working with for these campaigns?

Pius: Shifting from fossil fuel transportation to low carbon transportation is important. But instead of private electric cars, we need to promote more public transportation. This needs less nickel or electric batteries in total compared to private electric cars, so it can reduce over-extractivism. Also, if we move to private EVs in the cities, it will not solve the traffic jams. It may be a partial solution for air pollution in cities, but then it causes air pollution in the rural areas where nickel industries are based, including in the coastal areas. I should mention that fishing communities are also facing problems from nickel extraction because of sedimentation or degrading seawater quality in the areas they rely for fishing.

We are dialoguing with the governments in Indonesia to support more public transportation, such as electrified buses. Many passenger buses in Indonesia are also made in Germany, and they need to move now to electric vehicle buses. Mercedes buses are quite common. We see there is development by industry and government, but it needs to be more ambitious because we also see bigger and bigger private EVs, which need more materials from mining areas.

Our collaboration is mainly with the unions in the coal-powered plants or coal mining because we are moving through a just energy transition, so these workers need to be prepared.

Right to Repair

Katie: Thank you very much for sharing that Pius, it’s really interesting to hear about the campaigns for electric public transportation. Michael, could you say a bit about some other technologies you mentioned, and maybe about the right to repair?

Michael: About smartphones, the value of raw materials inside a smartphone is only a few euros. I heard once the figure of 1,11 euro as the raw materials value in a phone sold for 400 euros. So this is a huge challenge. The Right to Repair, as agreed by the EU in I think February 2024, now has to be transposed into national laws. The newest manufacturers will be required to repair a selection of common household appliances. Sadly, the scope is limited, not covering all electronic goods. But it gives consumers the right to borrow an appliance while their own is being repaired. In some German provinces we now have a kind of repair bonus of 50 to 100 euro if your smartphone is broken. So there is some progress, even if the scope is limited.

Longevity is also a big issue. We talk about circular economy and we think ‘that’s perfect, because metals are not gone like coal we burn’. But a lot of metals are used only in nanotechnology, less than millimetres, as a layer somewhere. So they are wasted, or dissipated. They are in such thin layers or even mixed that we cannot get them back economically and technically. There is an example of the old combustion engine, the catalytic converter [which injects very small amounts of platinum into fuel to make it burn more efficiently], that is distributing platinum on the German streets. We don't have enough energy in our solar system to get this platinum back as usable material. The platinum is there, but not available for humanity anymore. It is dissipated.

I asked some researchers: ‘what is the highest possible recycling quota we could reach with materials?’ They said it could be 70 to 80%. So even in a perfect world we are losing 20 to 30% of the material as nanoparticles, or in other ways. We use a smartphone for two years and after that, we are losing, in a perfect world, 20% of the material. So, a lot of the critical raw minerals, like gallium, germanium or rare earth elements, are used only for that product lifespan, and after 10 years, nearly 100% of these materials are gone, wasted, like fossil fuels. The Right to Repair is a step towards increasing the longevity of a product and product parts.

We are also not prepared for materials that will come in the future. We are building lots of offshore wind power facilities, which is a good thing, but we use rare earth elements for the magnets and turbines, but we don't have a clue about how to get them back on land, where to store them and where to make the rare earth elements in this turbine, to reproduce for the next generation of wind turbines. At the moment, for wind turbines we have a downcycling of the magnets, which are used in batteries, pedelecs, ladders or other applications inside wind towers. But after that, they are gone. It would be better to have them refurbished to keep them in the original use as magnets for wind turbines. We have to prepare for that, because a lot of wind turbines will reach the end of their lives in the next 10 to 15 years.

Katie: Are there peoples’ movements behind the European Right to Repair?

Michael: I know the Right to Repair Europe Alliance did an amazing job. In Germany it is the Roundtable Repair, and they organize activists and local repair cafés, where you can bring your broken record player, smartphone. But this is an interesting example of organizing from the bottom up and raise issues. The German Roundtable on the Right to Repair worked for around 10 years and they lost some issues on the accountability of the producers, etc. But in NGO speech: it is the first step in the right direction, and this was the first two or three steps in the right direction.

Historically, there was much more focus on repair. I would like to use my smartphone for as long as possible, but it’s often a software issue. It would be good to have regulation so that accountability is not with the person using it but the producer.

Katie: How do you see the responsibility of corporations here, and the role of legislation to create accountability?

Michael: Design is a really important question here. I often hear it is better to 'screw it' than 'glue it'. This applies to nearly all things, including solar panels on your rooftop. If you can screw it, you can loosen the screws and exchange things, but if you 'glue it', you have to break it in the end.

We visited the biggest German recycler of mobility batteries. I was surprised how small he is, but this shows how hard the fight against the combustion engine is in Germany. He showed us the manual steps to remove the battery cells from the packaging, to make sure there is no electricity remaining. They prepare everything and send it to a battery company who will do the actual recycling because this needs a lot of chemicals.

We also had trade unionists with us, asking about the working conditions. I am not sure how these workers are unionized, but this is a task for trade unions. Because there are new green jobs coming. This is the future. We have to prepare for recycling battery cells in the future. All the workers have to be unionized, also if they do this job for buses and other battery cells.

We talked to recyclers of the whole car, and they say ‘we have so much carbon, glue and other things used. This is not helpful in the recycling process. For us, it’s good if it is as clean as possible’. This is aluminium scrap, this is iron scrap, this is copper scrap, and then we don't need much energy. And we have a good product, nearly the same product in the end.

Offloading waste

Katie: You mentioned that recycled materials tend to be more expensive, because recycling uses a lot of difficult manual labour, and with this mixing of materials, this labour is difficult to automate. Historically Europe has tended to reduce labour costs by shipping waste to places with worse labour practices and standards. What are your thoughts on that offloading of waste onto the developing world, and creation of dirtier jobs elsewhere? How might we deal with that?

Michael: This is a crucial issue, especially if we talk about electronic scrap being shipped to Sub-Saharan Africa, without good working conditions, without taking care of health, living wages. They often burn products just to get the gold and other precious metals. But there is also a lot of scope to improve the conditions, for example through training people doing recycling there. We need both approaches.

At the same time the framing of ‘waste’ is already part of the problem. Metals are not waste, and we should improve the situations to recover them. I would call myself an internationalist. In the end, I don’t care if recovering materials is done in Germany, the Netherlands, UK, France, Sweden, Bulgaria, or in Ghana, Peru, Philippines, Indonesia, Mongolia, or wherever. It is a question of standards: make sure workers' rights are respected, make sure they can unionize, make sure human rights, environment standards, right to health, right to education, right to clean water, etc. are not violated.

A lot of industry people say 'these are our raw materials and let’s keep them here!'. They support free trade, condemning China for blocking exports, and arguing that Indonesia should export raw nickel. But when it comes to this ‘waste’ or scrap, they say: ‘no, no no, these are our raw materials.’.

As PowerShift, we are not free trade advocates, but Turkey needs secondary material for their steel smelters, because they don't have the technology to smelt primary materials to decarbonize their steel sector. They need to import steel scrap from Europe. So if we block exports, and say ‘this is waste and we should treat our waste ourselves,’ then Turkey has a problem with decarbonization of their steel sector. They will be kicked out of the auto supply chain, because the car industry is searching for 'green steel'.

This is the complexity with international raw materials trade, for primary as well as secondary materials. But we have to look at the product path, potentially, as a solution. Technology transfer from the Global North to the Global South. Maybe Circular Economy Partnerships, rather than Raw Material Partnerships, focusing on secondary materials, so they are not mined in the future in such large amounts. And think about regional circles.

In our talks with trade unions from the automobile industry, some expect that the automobile production will shift much more to the Global South. Transport is very high in CO2 emissions, so to reduce this, you have to produce near markets. For a circular economy, local markets are key: Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Chile need to have a local cluster to collect materials, and countries like Indonesia and Chile rebuilding or building smelters and refiners, need much more circular material. So, we should have global networks advocating for these.

At the moment, Indonesia is buying nickel from the Philippines because it is cheap and Indonesia does not have enough for all its new smelters. That supports their own industrialization, but for the Philippines, I don't see the benefit. It would be much better for Indonesia, Philippines and ASEAN countries to cooperate and consider a circular economy. And as Europeans, we should have accountability for this, regarding technological transfer beyond market opportunity, because we are benefitting from a system that has been in place for the last 300, 400 years.

Of course, there is a big difference between scrap and scrap. If you have electronic waste, smartphones, and 1 euro worth of minerals inside, there is a lot of waste. This is different from a car, which you can recycle more easily. But with the Battery Regulation, stated goals for recycling from mobility batteries are 95% of the cobalt, nickel, lithium in I think 2035. The industry is preparing, and factories are being built to reclaim the material. But what does it mean if the German automobile industry is exporting most of the cars? How can you make sure that these batteries are not ending up in a waste disposal in a country that cannot treat it? People are dumping cellphones and disposable electronics in the regular garbage. There is energy in these, which makes it dangerous waste, and another risk is that we end up exporting our risky materials.

Recycling and the future of nickel production

Yukari: That is a really interesting perspective. Pius, could you tell us a bit about where nickel being extracted in Indonesia is being used, and for what?

Pius: Nickel is used in some steel production, mainly for stainless steel, for construction, for cars, including fossil fuel cars, and aeroplanes, jet fighters. Nickel is quite light strong and corrosion resistant, so there are many uses. A lot is also used for batteries.

China is the main export destination for nickel from Indonesia, as the investment is also dominated by China. Some percentage later goes to Europe or other Asian countries. Indonesia is the biggest nickel producer in the world so we have confidence that all the industries in the world, including Europe depend on the nickel from Indonesia. However, the amount of nickel used inside Indonesia is quite small.

The government of Indonesia started to build nickel battery factories this year, for the first time. Electric cars and motorbikes have presence in the streets in Jakarta, although these are mostly not powered by nickel [batteries]. What we heard from the industries is that the motorbikes in Indonesia mostly use LFP [lithium-ferro phosphate] batteries. Nickel is used for more specialised vehicles that need a higher density of energy, so nickel batteries are mainly for export products, CATL and also TESLA are starting to use nickel from Indonesia. As we understand it, nickel production should be for the local economy and local technology.

Yukari: It’s interesting to hear that European industry is preparing for more recycling in the battery sector. Michael, how much public funding is going towards these initiatives?

Michael: Actually, one part of the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) of the EU are ‘Strategic Projects’. These could be primary mining, but also secondary material and recycling factories. We advocate for money and political support to recycling factories as strategic projects. Recycling and smelting is a very dirty, loud, dangerous industry. We should not have a romantic view of it. But for me, it could be a compromise, with less material use in the future, and changes in mobility behaviour, etc., while still having decent living standards that we can reach globally. We need some of these factories and improve them to be less dirty, loud and dangerous.

But I was surprised that the CRMA has the goal that 25% of future materials should come from recycling, and this is quite ambitious for rare earth elements, or others where we are currently lower than 10%. But it is under-ambitious for copper, aluminium and tungsten, where we already recycle more than that.

And disappointingly, recycling is still left as a national issue: the EU refuses to tackle it. It doesn't help if every city, or region or country has their own recycling structures and ideas. Because collecting, sorting is a question of scale.

We are still living in a capitalist system, so there needs to be some value for the private industry, otherwise you need better-funded local collection and sorting. But in a capitalist system, cities are in competition against each other, so we need ways to work together, which is quite hard to achieve. I wish the European Commission was better prepared, because these raw materials are crucial, not only for our industry but also for our societies. They are finite and we are losing them. That knowledge is there. The next step is to make this knowledge into practical instruments and measures to do more, use metals longer, recycle them better, and think where we use them for what kind of products.

Closing points

Katie: Your earlier point that we treat them as though they are renewable, because they are recyclable, but after 10 years they are effectively gone – that really requires some new thinking. Would you both like to share any closing points?

Michael: These are my favourite examples of how we waste raw materials: In 2022 a study in the UK found that so much lithium from disposable e-cigarettes was in the waste that we could use them for 4400 cars. And I learnt recently about disposable power banks to load your mobiles, and this is unbelievable! There should be a way to react on that politically, as a society. The same is true for 2.5 tonne cars used mainly in cities. So, we really need to be aware that metals are not there in the future as we think they are.

Pius: We need to minimise the need to mine, promote public transportation, and avoid mining in the protected forest, especially forests with high conservation value.

We need to reduce material consumption and this is particularly true for nickel in Indonesia, because it comes from the forest area and concentrated in only 4 of Indonesia’s 38 provinces: Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi and North Sulawesi. We need to avoid overburdening these areas. But of course, communities also need development. I visited communities in 2012, before this wave of extraction, and people told me they urgently needed roads, hospitals, education, not the kind of over-extractivism happening now, with its environmental and social impacts.

Digging Deeper

Full dossierConversations on Mining and Just Transitions

This series of conversations is aiming to explore challenging questions around mining and the energy transition, and the solutions that social movements are putting forward.

-

Digging Deeper An Introduction

Publication date:

-

Ending corporate impunity & realising the Right to Say No Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date:

-

Artisanal and Informal Mining Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date:

-

Mining, Land and Territories Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date:

-

Right to Repair and Circular Economy Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date:

-

Green Industrial Policy Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date:

-

Climate finance & Climate reparations Digging Deeper: Conversations on Mining and Just Transitions

Publication date: