The Many Scandals of the Border Industrial Complex

Topics

Regions

As election campaigns heat up, the true state of the border is revealed in record budgets, record contracts, increased border deaths, and the barring of press from the Border Security Expo in El Paso.

Photo by Todd Miller

All eyes were on Border Patrol chief Jason Owens when he took the stage on May 21 to deliver the keynote at the Border Security Expo—the premier annual event that brings border officials together with the private sector—in a conference room at the El Paso Convention Center. He was a key figure in the Border Patrol’s scandal involving a Mexican tequila mogul and the creation of a special blend for the Border Patrol’s centennial. According to an NBC report, Owens had been partying with distiller Francisco Javier González in Jalisco.

Owens, however, did not seem uncomfortable as he spoke in the crowded conference hall. He looked at the audience of mostly suit-and-tied industry people and addressed them directly. He thanked them for what they did “to bring these new ideas, business, innovation” that “help us get an advantage over a very serious adversary.” That word “adversary”—to describe cross-border threats—would be repeated multiple times by officials during the three-day event. “I know you guys are here on business,” Owens continued. “You’re here to make money.” But it “means the world to us. I want to thank each and everyone of you who contribute to the safety of our green family.” Border Patrol agents, of course, wear forest-green uniforms.

Photo by Todd Miller

And while Owens would go on to mention the “green family” several more times, he avoided mentioning the centennial tequila scandal. But as I watched the opening keynotes, and panels titled “The State of the Border” and “The Future of the Border,” I wondered if the tequila scandal was the right one to focus on. As Owens talked about potentially profitable technologies as “force multipliers,” and stressed the importance of “situational awareness” for agents, there was no press presence. For the first time in the 17 years of the Border Security Expo, media were barred from registering. I myself came in my academic capacity. In an era when border contracts doled out to private industry are the highest in history, there would be little scrutiny of CBP’s and ICE’s fomenting relationships with a multibillion-dollar industry and what that means for one of the most hotly debated issues during a presidential election year.

Carla Provost, chair of the Border Security Expo and former Border Patrol chief, described the expo as “a great opportunity for government and industry to come together to find solutions for border security challenges.” But without press, serious questions went unanswered: How might the profit motive influence how border and immigration enforcement work? How much clout and influence do companies have in Washington when it comes to strategy and policy? How are the “solutions” brought to the table to begin with, and under what criteria? Are border communities and civil society consulted?

Photo by Dugan Meyer

Some of the “solutions” were on display in the exhibition hall, where nearly 200 vendors—large and small—displayed their wares. It was a thicket of surveillance technology where robotic dogs courtesy of Verizon and AT&T trotted on gray carpets, large monitors showed off AI-fueled camera systems, and armored all-terrain vehicles were backed by a large video screen that depicted them rumbling through war zones. There were mannequins with helmets and headsets and bulletproof vests looking like they could take over El Paso on command, fake border walls armed with “smart” technologies, BuckEye camouflaged cameras.

Photo by Dugan Meyer

There was facial recognition, biometric systems, cybersecurity, heart beat detectors, command centers, rugged laptops, and kinetic dog food for sale. The dog food advertisement exclaimed, “No corn, soy, or fillers! No BS!” Underneath, a running, growling dog—wearing a tactical vest and backdropped by a helicopter—chased someone, presumably an “adversary.”

The border, one might presume by the looks of the exhibition hall, is a never-ending war. And El Paso—where border crossers died in record numbers last year—was in the middle of this war zone.

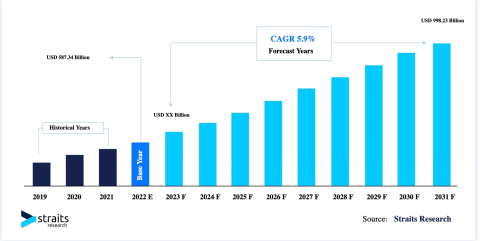

As in other years, entering the expo felt as if you were peering into a crystal ball, the soothsaying of an industrial complex, of a border more and more digitized and increasingly fueled by artificial intelligence, in a global homeland security market projected to reach nearly a trillion dollars by 2031 (from $587 billion in 2022). It is expanding, according to Straits Research, at a “rapid rate.”

https://straitsresearch.com/report/homeland-security-market

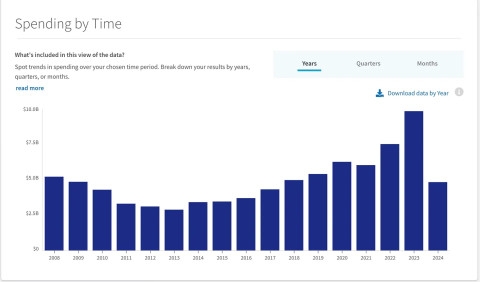

Despite the mildly dour mood at the expo resulting from the tequila scandal and cancellation of the Border Patrol centennial anniversary gala, there was a lot of room for optimism. According to Provost, this year’s expo was the largest ever in terms of company participation. And in the United States, the total border and immigration enforcement budget for 2024 (CBP and ICE added together) has exceeded $30 billion for the first time ($30.2 billion), not only a record high but nearly double the budget from when I first attended the expo in 2012. Since the 1980s, enforcement budgets have increased year after year, regardless of party and president.

But there are more reasons for industry optimism: issuing private contracts for border and immigration enforcement has become a staple of the Joe Biden administration. The $28.1 billion of contracts issued under Biden since 2021 already has outdone Trump—who doled out $20.9 billion during his four years—by quite a bit. Last year was the largest ever recorded for contracts, at $9.8 billion, a total of 8,729 contracts, with an astonishing average of 45 contracts a day to a variety of companies. As it stands in 2024, there are thus far 3,741 contracts, worth $4.8 billion, which seems like it might fall short of last year’s record, but that remains to be seen with nearly four months to go in the fiscal year and this year’s hefty budget.

Regardless, Biden will end his first tenure as the top contractor for border and immigration enforcement, a far cry from the “open borders” narrative that pesters him at every turn.

usaspending.gov

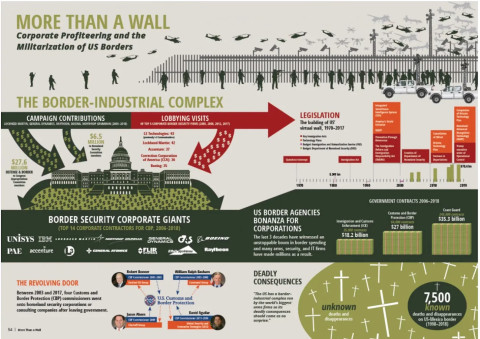

There were, of course, hints that this might happen. A study on campaign contributions after the 2020 elections showed that Biden received three times from top border industry companies than Trump, and that Democrats topped Republicans 55 to 45 percent. This doesn’t mean that the industry necessarily favors Democrats; it is more amorphous, leaning toward whatever is most advantageous, and often both sides at the same time. Top border industry companies such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Accenture, and CoreCivic also regularly get behind closed doors in Washington, influencingpolicy, strategy, and appropriations discussions. Companies will also use the Border Security Expo to ask the federal government for more money, which is what Palmer Luckey, founder of the surveillance tower company Anduril, did in 2022 in San Antonio (as reported by The Border Chronicle).

TNI

Back at the podium, Owens explained how hard it is to control the border. He calculated 7,500 miles just counting the Mexican and Canadian borders. Imagine, he asked the audience, how many agents you would need, how much assistance you would need to cover all these miles. “We need more people. We need more stuff,” he said repeatedly to a sea of nodding heads. It wasn’t just protecting the green family that needed protections; we need, he said, to protect “our way of life.” While Owens was stressing how overwhelming, if not impossible, the border enforcement mission is, I wondered if what he described was also tantalizing to industry, showing all the areas of potential market growth.

But without press, there was no way to ask. You couldn’t ask about the budgets, the profit, the record contracts. You couldn’t even ask about the tequila scandal. All you had was the expo narrative of security, innovations, and adversaries. Eventually, I needed to walk out into the fresh air.

Photo by Todd Miller

Luckily, the El Paso Convention Center is a mere 10 blocks from the border. Up on top of the Stanton Street bridge, I looked down onto the sickly, trickling, polluted Rio Grande, surrounded by razor wire and walls, stared at by cameras and agents and police. This was how all that stuff in the exhibition halls looks on the actual border. In the past couple of years, I’ve seen huge groups of people wade through the contaminated water to get to the large wall on the U.S. side. I thought about the 149 people who died crossing the border in the El Paso sector in 2023. Perhaps the tequila incident was a big deal, but the real scandal wouldn’t be reported at all.