The municipalist drive for a fair and participatory energy transition Energy tables in Cádiz, Spain

Topics

Regions

In May 2015, the party Por Cádiz Sí Se Puede (the local version of Podemos) took over the government of Cádiz, inheriting a situation of massive debt, widespread energy waste, severe unemployment, energy poverty, and a lack of public awareness around energy issues. In just a few years, however, Cádiz has celebrated a number of concrete results.

By Alba del Campo, feminist, ecologist and journalist who has been advising the Cádiz City Council about the energy transition and coordinating the city’s energy tables

Affected population 118,919

First of all, the local company Eléctrica de Cádiz now supplies 100 per cent certified renewable energy, impacting every municipal supply contract and 80 per cent of household consumers. Secondly, a pioneering alternative proposal for a ‘social discount’ is expected to guarantee access to energy for more than 2,000 families each year. And finally, the discussion around the energy model has been brought into the public sphere, both within and beyond the city’s institutions.

This has all been achieved through partnerships between the City Council and citizens gathered in two open and participatory roundtables: one to specifically tackle energy poverty, and the other with the longer-term mandate to spur a municipal transition towards renewables.

Beyond these direct achievements, there have also been positive indirect impacts. Due to the Council’s commitments to sustainability and energy transitioning, a new electric bicycle and motorcycle factory will generate 200 new jobs in the city. Furthermore, Eléctrica de Cádiz, 55 per cent of which is owned by the municipality, has secured the contracts to supply 100 per cent certified renewable energy to two nearby municipalities that were previously in the hands of the oligopoly.

Cádiz has quickly become an example of how a municipality, a semi-public energy company, and a people can together ignite the transition to renewable energy. This shows that the right to energy, increased employment and a transition towards renewables can in fact go hand in hand.

A peculiar starting point

In May 2015, two recently created parties, Por Cádiz Sí Se Puede (For Cádiz, Yes We Can) and Ganar Cádiz (Win Cádiz) won the municipal elections in the city of Cádiz, Spain. This put an end to 20 consecutive years of government by the conservative party, the Partido Popular (PP). With the economic crisis heading into its eighth year, this change took place in the midst of widespread questioning of the political-institutional model and its local reforms based on austericide.

Cádiz is a city of contrasts. The image of an ideal holiday destination clashes with the fact that it is the provincial capital with the highest unemployment rates in the European Union (EU). Upon entering office, the new Por Cádiz Sí Se Puede municipal government discovered that it had inherited not only a municipal debt of € 275 million, but also an urban development model that had clearly failed. The city’s population had dropped from 160,000 inhabitants in the 1980s to 119,000 in 2017.

Although Por Cádiz Sí Se Puede was elected to the municipal government with renewable energies and an energy transition as an engine of job creation high on its agenda, the new government had to start from scratch. Remarkably, even though Cádiz is among the sunniest cities in the EU (with over 3,000 hours of sunshine per year), its solar energy production does not cover even 0.001 per cent of the electricity consumed there.

Furthermore, Cádiz is in the unique situation of still having two semi-public electricity companies. The municipality owns 55 per cent of Électrica de Cádiz (the remaining 45 per cent is owned by Endesa and Unicaja), which consists of one distribution and one supply company. This is the largest private-public power company in the country, with over 60,000 power contracts. Users include all of the city’s municipal entities, as well as 80 per cent of the households and services.

What benefits does this semi-public energy company provide for the population of Cádiz? First, the municipality uses the revenues to cover the cost of supplying energy for municipal buildings, public lighting and traffic lights. Any remaining profits end up in the city’s treasury, increasing public spending. Furthermore, these revenues have allowed the city to allocate a substantial amount of funds (more than € 500,000 in the last two years) towards occasional emergency aid and to partially subsidise the energy bills of low-income pensioners. In other words, 55 per cent of the revenues are reinvested in Cádiz.

It should be highlighted that current Spanish national regulation does not protect low-income families from being cut off from the energy supply. Yet since Eléctrica de Cádiz is semi-public, the city’s social affairs department has been able to maintain direct and regular communication with the company in order to to save thousands of homes from power cuts every year.

National laws impeding the energy transition

With regard to energy policy, it is worth highlighting that Spain’s regulatory framework strongly favours the dominance of large energy corporations and hinders the entry of new actors onto the market. The country lacks a strategic plan for energy transition, and the progress made in the 2000s was followed by huge setbacks just a decade later. Unfortunately, Spain is renowned for having some of the world’s most restrictive regulations on the self production and self consumption of renewable energy. The mainly socialist governments that have ruled the country stimulated private investment in renewable energy by offering premiums guaranteed by the state. However these governments, along with conservative party (PP) governments, also introduced between 2008 and 2013 retroactive measures that reduced payments to investors. This gave rise to investor-state dispute settlement claims, in which international investors have been suing the government of Spain for hundreds of millions of euros. Furthermore, these measures were taken at the expense of ordinary citizens, and 60,000 families lost the savings they had invested in renewable energy. This generated unprecedented legal insecurity for citizens, investors and energy companies, and led to the elimination of more than 30,000 jobs in the renewable energy sector.

In this context, the new municipal government of Cádiz aims to promote a just energy transition by adopting four main lines of work: 1) savings, efficiency and renewable energy in public buildings; 2) the fight against energy poverty; 3) the promotion of a democratic energy transition; and 4) the promotion of job creation linked to energy.

Starting from scratch: monitoring municipal energy consumption

In 2009, the Cádiz City Council signed the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, thereby committing to a 21 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions by 2020. However the ensuing Sustainable Energy Action Plan, presented in 2013, lacked achievable goals, concrete strategies and follow-up tools, and did not create any real momentum for an energy transition. The conservative government also failed to plan any investments in energy efficiency or renewable energy, or to carry out an energy assessment for the city, or to establish a structure for the implementation of the plan.

One of the main objectives of the new municipal government is to take advantage of local renewable energy resources, including the possibilities offered by the port and shipyards. This would promote an energy transition that would serve as a driving force for change in the urban development model, and would help to rebuild the city’s social and productive fabric. The municipality’s first action was to conduct an internal energy assessment; this revealed a tremendous lack of control over municipal energy consumption. It also exposed a culture of rampant energy waste; the lack of investment and poor maintenance of infrastructure; a deficit of knowledge about energy issues among municipal workers and public representatives; and a complete absence of the necessary human and technological resources for the efficient management of energy.

This is why the new administration’s initial measures were aimed at regaining control over municipal energy consumption. The Centro Municipal de Informática (the municipal IT centre), in collaboration with Eléctrica de Cádiz, has created an online database on energy consumption that allows the close monitoring of costs, consumption and CO2 emissions at each point of supply. It also established a monitoring committee, and a municipal technician exclusively dedicated to energy management has been assigned to each area. Research has been undertaken in order to implement energy efficiency measures in buildings with high energy consumption, and projects to introduce renewable energy in public buildings have been developed. The municipality has applied for funding from the Autonomous Region of Andalucía in order to carry out these projects.[1]

The municipality has taken up the challenge of involving local people in carrying the energy policy forward. Eager to start working with local social and environmental organisations, the city created two working groups on energy even before it had a plan: the Mesa contra la Pobreza Energética (Roundtable against Energy Poverty, or MCPE) and the Mesa de Transición Energética de Cádiz (Roundtable on the Energy Transition in Cádiz).

The social discount of Cádiz: a first step towards guaranteeing the right to energy

At an October 2015 Council meeting, the municipal government unanimously approved something that a number of citizens’ groups in the city had been demanding for years: a social discount to guarantee access to energy for vulnerable families. This proposal was different from the state’s programme, which only provides a 25 per cent discount on energy bills. The social discount proposal stipulated that the design of the energy subsidy would be drafted by a working group open to the public, and the MCPE was created for this purpose.

Why did the people of Cádiz want a different kind of discount? Between 2009 and 2017, 80 per cent of the families in Cádiz were not eligible for assistance from the national programme. This was because they did not get their electricity from certain private energy corporations, such as Endesa and Iberdrola, but rather from Eléctrica de Cádiz, the company that had always supplied them with energy.

MCPE implemented a participatory process to design the future Bono Social Gaditano (Social Discount of Cádiz). Ultimately, the proposal was built collaboratively by the activist groups and human rights organisations that had been demanding its adoption for years. These groups had been working to give visibility to the problem of energy poverty in the city, together with organisations that help families to pay their energy bills (including Caritas, the Red Cross, the Virgen de Valvanuz Foundation, the Dora Reyes Foundation, APDH, 15m and the Cardijn Association, among others); experts from the city’s department of social affairs; political representatives from all parties (except the PP); the personnel of Eléctrica de Cádiz; and people suffering from energy poverty.

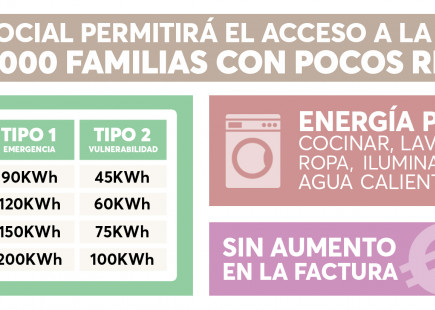

During the process, participants defined the criteria for access to the subsidy and agreed to establish an energy efficiency training as a requirement for beneficiaries. It was decided that instead of providing a 25 per cent discount on energy bills (as the state subsidy did), the Gaditano discount would offer a reduced tariff for the amount of energy and power each family needed in order to live a dignified life.

To complement the proposal, the Colegio de Ingenieros Técnicos de Cádiz (College of Technical Engineers of Cádiz) carried out a study on the energy needs of vulnerable families. Suggestions from a number of technical and legal reports were also included in order to ensure that the proposal was technically and legally viable. Once endorsed by the citizens’ groups, the proposal was submitted to the Board of Directors of Eléctrica de Cádiz for a vote.

Despite obstacles created by the Popular Party and Endesa, at the time this article was published Eléctrica de Cádiz and the municipality were working hand in hand to implement the first alternative social discount in the Spanish state. This discount is expected to guarantee access to energy for more than 2,000 families each year. Because Eléctrica de Cádiz is legally prohibited from changing its rates, the funds to cover the costs of this aid will come from a voluntary donation of profits from the energy distribution company. Conversely, the big energy companies that are part of the national discount programme pass the costs of their discount on to their consumers.

As an illustration of the difference in the two benefit schemes, in Cádiz a family of four (with two adults and two children) would be entitled to a discount of at least double what is offered by the national programme (€ 28.50 compared to € 12.95). In addition to this social discount, households are given insight into the specifics of their bills, and are trained to use energy as minimally and as efficiently as possible. With the full assistance of the social discount programme, energy bills may decrease by up to 80 per cent.

Parallel to the adoption of the Gaditano discount, the city launched an Emergency Plan against Energy Poverty. Also, through the Plan +30-30 job creation programme, 15 unemployed individuals are being trained as energy consultants for homes and small businesses. Half of them will work for the city advising, training and accompanying families living in energy poverty. During the first four months, the training team offered 50 workshops and trained 525 vulnerable families; and in cooperation with Eléctrica de Cádiz, they have improved the energy contracts of 415 vulnerable families to achieve savings between 10 and 40 per cent.

The Roundtable on the Energy Transition in Cádiz: building a common path

The Roundtable on the Energy Transition in Cádiz (MTEC) was created as a permanent space for participation and collaboration. Open to organisations, citizens and companies, the MTEC meets every two weeks to develop actions and proposals to push for changes to the city’s energy model. Municipal specialists, environmental organisations, individuals, employees of the University of Cádiz and Électrica de Cádiz, and members of the Som Energía cooperative participate on a somewhat regular basis.

The MTEC, which operates horizontally and by consensus, was created in November 2015 during the city’s first conference on energy transition. This roundtable promotes the conversion of the Électrica de Cádiz supply company to 100 per cent renewable energy sources. The MTEC carries out various popular activities in the city to raise awareness and to build momentum for the transition to renewable energy. The roundtable organised the city’s first Social Pulse on Energy survey, and organised an Energy Culture Week with workshops, conferences and a local fair. Furthermore a Popular Energy Literacy campaign is being developed, and reflections and debates on gender and energy have also been launched.

With the transition to renewables, Eléctrica de Cádiz has improved the environmental ratings of all of its municipal building contracts as well as those of 80 per cent of the families in the city. The city’s electricity company buys certified energy, generated from renewable sources, and sells it on to its customers. Eléctrica de Cádiz has also managed to win contracts to supply energy to two other municipalities in the province (previously served by companies forming part of energy oligopoly). These new contracts were possible because the tender documents included a requirement to provide 100 per cent certified renewable energy.

Despite the fact that Eléctrica de Cádiz board members nominated by the municipality are in the minority (five of the nine members are from the conservative party and Endesa), a business line dedicated to renewable energies and a gender equality plan have recently been approved.

Taking the city’s social pulse on energy

The Social Pulse on Energy in the City of Cádiz was the first municipal survey conducted in Spain on what citizens know about the most basic energy-related issues. People were asked how well they understood their energy bill; what energy model they wanted for their city and their country; and what steps towards energy efficiency they thought their municipality should take.

The survey emerged from the need to establish a baseline for an energy responsible culture. It was designed and elaborated by MTEC participants, and consisted of 450 interviews conducted on the street. Once completed, the study was presented to the municipal government with a series of recommendations to the City Council, Eléctrica de Cádiz, and citizens on how to promote a better culture for sustainable energy use in the city, and how to prioritise actions to this end.

Some interesting data can be found in the results: 70 per cent of the people surveyed said that they did not understand their energy bills. Of the 30 per cent who believed that they did understand their bills, their answers to some simple verification questions revealed that this belief was wrong. Among the measures identified as priorities, the most popular was to change public streetlights to LED. Ranking second was training and awareness campaigns on how to save energy; third was the adjustment of the time schedule of the public lighting system; and fourth was a switch to renewable energy in public buildings. It should be highlighted that 9 out of every 10 people interviewed had difficulty in distinguishing renewable energy sources from fossil fuels. However, it is important to note that 92.6 per cent of the people surveyed indicated that they would like the majority of the City of Cádiz’s energy supply to come from renewable sources.

The Popular Energy Literacy campaign currently underway is based on the idea of helping by empowering. Every week, MTEC participants go to a different neighbourhood to give a workshop on saving energy in collaboration with other local actors (neighbourhood associations, women’s groups and NGOs). In addition to helping participants to save money, a culture of socially and environmentally responsible energy use is promoted during the workshops, and neighbours are encouraged to play a leading role in an energy transition that responds to their interests.

All of these initiatives are taking the energy model debate to the street and to local institutions. People are now questioning the current model and demanding change. What is more, the political pressure for a more sustainable and renewable urban model is producing its first positive results in terms of increased employment.

At the beginning of October 2017, the Torrot company announced its decision to open an electric bicycle and motorcycle factory in Cádiz, which would generate (directly and indirectly) 200 jobs. The company president stated that one of the main reasons for choosing Cádiz was the municipality’s policies on mobility and energy. In a city with an unemployment rate of 28 per cent, this announcement brings new hope and gives a major boost to the municipalist strategy.

To continue promoting this democratic energy transition, the municipal government plans to elaborate a participatory process for a Roadmap to Sustainable Energy by 2030, before the end of its term in 2019.

Conclusions and lessons learned

The new City Council and citizen’s groups in Cádiz are aware that the road towards a renewable energy model could deepen current social inequalities and exacerbate the environmental crisis. For this reason, they realise that it is essential to involve public administrations, companies, social organisations, universities and civil society in building a fair energy transition from the bottom up.

The organisations and local people that have joined forces in the Roundtable against Energy Poverty have successfully designed a social discount programme for families living in the city. This plan is a much better one than that created by the Spanish government. Within the Roundtable on the Energy Transition, a small group of people have proposed and are promoting measures to change the energy model using the tools they have at hand and taking community needs into account. All of this has been made possible through the support and involvement of the municipality. The most important lesson that can be drawn from this is that – with active citizen engagement – a semi-public energy company can bring real benefits to the population.

It must, however, be pointed out that none of the above-mentioned changes have been easy to achieve, and that the number of people participating in the energy roundtables is not huge. This may be due to unemployment, job insecurity or the ageing of the population. Also, we have not mentioned the shameful role that some politicians and the media have played in this process; the conservative party for example is doing everything possible to boycott the Bono Social Gaditano. Despite these obstacles, the energy democracy movement in Cadiz is now closer to proving that achieving the right to energy is a feasible goal.

[1] The Cádiz City Council submitted seven projects, all of which were approved by the Andalusian Energy Agency. It is expected that these projects will be carried out in 2018.