Tying up Goliath Activist strategies for confronting and harnessing digital power

In recent years, the Right has been more successful at using digital tools than progressive movements. What are the strategies and tactics, progressive movements can use to build digital counter-power?

illustration by Zoran Svilar

The last decade has seen a sweeping change in our perception of social media platforms and their role in social movements. Within the wave of protests in 2011, from the so-called Arab Spring to the Occupy mobilisations, such platforms were often presented as technologies of liberation. Ten years on, however, social media have come to be seen as spaces of surveillance and repression that are captured by capitalism and authoritarian governments. The Edward Snowden revelations in 2013 were a turning point in this regard, when the role of commercial social media platforms in the surveillance of activists was made abundantly clear. Since then, many mainstream social media platforms have been saturated by misinformation and offensive speech. They have often been seized by far-right forces that, under the banner of ‘free speech’, have used them to ruthlessly attack their opponents. In 2022 we may have seen another turning point in this tale, as this was a year when the power of social media faced intense challenges. The chaotic takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk, the recent losses in the value of Meta (formerly Facebook), and the growing calls to regulate content on these platforms have been accompanied by a modest exodus from social media, and Twitter in particular, and the migration to alternative platforms such as Mastodon, even though this move might be short-lived.

Of course, mainstream social media platforms still hold significant power. They have become important conduits of news and information with research both in the US and the UK showing that platforms like Facebook and YouTube are increasingly spaces where users get their news. The business model of such platforms promotes ‘surveillance capitalism’, the relentless gathering and selling of data on user behaviour. The companies behind them have also become too big to regulate and control, as they have been steadily acquiring smaller start-ups and adding diverse platforms and applications to their list of products. So, although social media platforms may have offered more opportunities to users to express their voice, they still reinforce the capacity of the powerful to shape public opinion as they have the resources to pay the fees charged by some of these platforms, to conduct black propaganda through bots and fake accounts, and to invest in digital ad campaigns. These platforms also have an ambivalent relationship with repressive regimes around the world, sometimes colluding with them – as the Snowden revelations amply showed – and sometimes providing a channel for dissent that is not controlled by the government, even though it is still shaped by complex geopolitical interests.

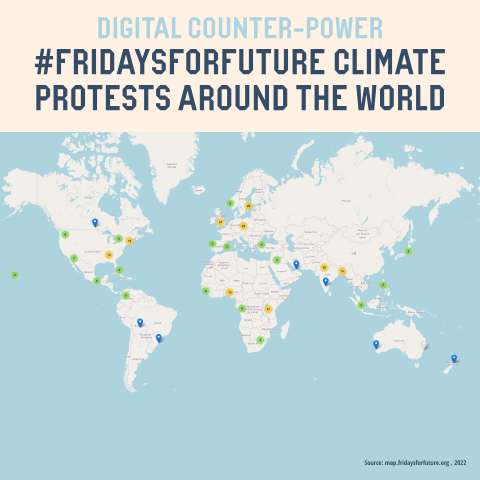

Within this landscape, progressive activists need to both challenge and harness the power of social media in an effort to build the world that they’d like to see. But how can social movements do this? And what are the obstacles they face along the way? In this essay, we explore some strategies that activists can use by focusing on the example of the environmental movement, and particularly groups and organisations mobilising against climate breakdown. These are diverse and heterogeneous, ranging from traditional non-government organisations (NGOs) and charities, to more recent groups like Extinction Rebellion (XR), which focus on direct action, to mobilisations associated with Greta Thunberg and the Fridays for Future movement.

Our analysis draws on the work of social movement scholar Dieter Rucht on the strategies that activists adopt when dealing with the tendency of the mainstream media (MSM) to misrepresent, trivialise and marginalise activist causes. In the early 2000s, Rucht observed that, in response, some activists decide to put visibility aside, and abstain from the mainstream press. Others opt to openly blame the mainstream press in an attempt to make them accountable for their biased reporting of protest. Still others choose to bypass the mainstream press by creating alternatives to cater to their constituencies. Finally, some groups attempt to get good mainstream media coverage by seeking to understand how the media work and by adapting their communication to them. Rucht’s framework was named the ‘Quadruple A’ as each of the four strategies begins with the letter ‘A’: Abstention, Attack, Alternatives, Adaptation. While Rucht’s strategies originally referred to an age of dominance by the mainstream press, they still resonate today when social media platforms, as well as the press, take centre stage in the communication strategies of activist groups.

Since the mainstream media follow a capitalist model, it comes as no surprise that these four strategies echo Erik Olin Wright's (2019) discussion of the four logics that characterise anti-capitalist struggles: smashing, escaping, eroding, and taming capitalism. When activists engage in collective action with the logic of smashing capitalism, they are in tune with communication strategies that revolve around attacking social media platforms. Similarly, when activists promote collective action that would allow people to escape capitalism, they are consistent with the strategy of abstention from social media platforms. When activists develop collective action that does not wholly reject capitalism but, rather, seeks to tame it, we can see a resemblance with the strategy of adaptation. Finally, anti-capitalist struggles that aim to erode capitalism link to activists who are creating alternatives to social media platforms, building and curating spaces of contention that they can manage directly.

Keeping in mind these different anti-capitalist logics and the four strategies that activist groups might employ to address the issue of visibility, we explore how the environmental movement has engaged with social media platforms.

Abstention (Escaping Capitalism)

Strategies of abstention involve shunning the mainstream social media completely as a form of both protest towards and protection from their business models and surveillance mechanisms. Deciding not to delegate your group’s visibility to the profit logic of social media platforms is liberating. It frees activists from the constant pressure to be visible and produce content on these platforms. It also emancipates activist groups from the opacity that characterises social media algorithms – black boxes whose functioning is difficult, if not impossible, to understand. The strategy of abstention can promote more sustainable ways of maintaining membership beyond Facebook groups or Twitter threads, by developing the group’s own media.

It can also protect activists from online attacks and surveillance. As the case of Greta Thunberg has shown, prominent activists can be the targets of scathing attacks on social media that range from trolling to death threats. Being present on social media also renders activist groups vulnerable to surveillance by the authorities. This is particularly dangerous for activists who use tactics of civil disobedience or push the lines of legality. Such groups thus typically engage in face-to-face planning rather than online coordination. Therefore, abstaining from social media platforms is crucial for enhancing the privacy and data integrity of internal organising.

Alongside abstention, some activist groups have also launched campaigns urging people to disconnect from such platforms or to engage in practices of digital or data ‘detox’. For instance, Tactical Tech provides a tool kit for creating awareness of the data traces that we leave online and for developing alternative practices for what they call ‘a more confident relationship with technology’. Disconnecting from social media may also be done for environmental reasons. As Tactical Tech notes, digital detox strategies can help in the fight against climate change as digital technologies are now responsible for 3.7% of the world’s global carbon emissions, a figure that may increase to 8% by 2025. ‘That's currently more than the civil airline industry, and soon it's predicted to surpass the automobile industry, too.’ Environmental groups may therefore opt to abstain from social media in order to reduce their e-waste and carbon footprint.

However, ‘digital detox’ practices are often related to individual lifestyle politics rather than collective efforts to achieve systemic change. Attending digital detox camps or restricting our digital data footprints by using specific browsers and configurations involve individual practices and ways of relating to social media. They may thus have a smaller impact on challenging capitalism and Big Tech than seeking to promote structural change through regulation, for example.

Furthermore, a complete abstention from digital platforms seems virtually impossible, especially for political causes with a transnational character or those aiming to mobilise large numbers of supporters. In a world where visibility on social media has become crucial for expanding a movement’s community, abstaining from these platforms means cutting oneself off from a dense network of relationships that has sustained numerous protests around the world over the past decade. The environmental movement is no exception, as evidenced by the extensive use of social media by organisations such as Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion or movements like Fridays for Future. Instead, and as we note in the sections on the strategies of Adaptation and Alternatives, activist groups often choose to use mainstream platforms for promoting their cause to a broader audience, even if they abstain from using them for internal organising.

Attack (Smashing Capitalism)

Activists and social movements can also attack social media platforms and campaign for them to reform their corporate practice or the regulations governing their operation. ‘Attack strategies’ include anti-trust actions that challenge the size and concentration of social media companies, as well as digital rights campaigns that target the misuse or misappropriation of data by companies and national governments.

There are also many campaigns against disinformation on social media, a problem that is also enormously affecting campaigns on climate change. Large polluters such as oil companies engage in elaborate greenwashing campaigns on social media. False statements regarding climate change have proliferated, often peddled by fake accounts and ‘astroturf’ campaigns. Climate change denialism is rising on social media platforms, also as a result of the strengthening of far-right accounts and the lack of effective moderation. In February 2022, Reuters reported that Facebook ‘failed to flag up half of posts that promote climate change denial’. Research undertaken by Global Witness has found that the Facebook algorithm not only locks climate-sceptic users in echo chambers of climate denialism but also directs them ‘to worse information, so that what began on a page full of distract and delay narratives, ended on pages espousing outright climate denial and conspiracy’. On Twitter, the situation seems to have worsened after Elon Musk’s takeover, which led to the firing of content management teams, the dismantling of the platform’s sustainability arm, and the return of banned users to the platform, some of whom have a significant history of climate denialism. Consequently, the hashtag #ClimateScam has climbed in the rankings and is ‘now regularly the first result that appears when ‘climate’ is searched on the site’.

Campaigns against disinformation on social media have included the #StopHateForProfit campaign in 2020, in which various civil society groups and organisations called on advertisers to boycott Facebook for this reason. The campaign was initiated by a coalition of activist groups, including the Anti-Defamation League, Free Press, and GLAAD. In February 2020, Avaaz ran a campaign specifically about climate change denialism on YouTube and other platforms, which was based on a detailed report compiled by the organisation. Avaaz called ‘on all social media platforms to detox their algorithms by ending the amplification and monetisation of disinformation and hate speech’. It also urged ‘regulators to turn this into a legal requirement’ and demanded that ‘platforms work with independent experts to track and downgrade creators of repeated and deliberate disinformation’. It is worth noting that the group amended the initial text of the petition to remove a ‘demand to “deplatform” creators of repeated and deliberate disinformation’. While no reason was given for this amendment, we suspect that it relates to the slippery slope when demands to deplatform individuals or groups peddling disinformation can be turned against progressive actors and used to restrain their voices on social media. Calls to boycott and deplatform should thus be alert to the implications for freedom of speech across the political spectrum. Furthermore, for such actions to be effective, they need backing from prominent activist groups and advertisers so that they are considered sufficiently effective for others to join and are able to draw sufficient news coverage.

Attacks can also occur more directly, such as through hacking. For example, Twitter and Facebook have been targeted by denial-of-service attacks in which computers prevent users from accessing the platform or slow down their use. Such attacks have not always been clearly linked to criticism of the platforms themselves, but to protests against the role of such platforms in giving voice to particular political viewpoints, for instance in relation to Russia’s conflicts with neighbouring countries. Yet, ‘hacktivism’ requires sophisticated technical skills and comes with the risk of arrest and other repercussions. This is probably why there are no recorded cases of environmental hacktivism, even by groups like Extinction Rebellion that focus on disruptive action (at least until their very recent change in strategy) although the group did engage in internal discussions about hacktivism during the pandemic. For the academic Gabriella Coleman, who has conducted extensive research on Anonymous, this may be because there are few overlaps between hardcore hackers and hardcore environmentalists, meaning that the environmental movement lacks the necessary skills and experience to engage in such activism. On the contrary, it is environmental activists who have fallen victim to hacking attacks. For instance, in 2017, environmental groups who ran a climate change campaign against Exxon Mobil received phishing emails by accounts impersonating their colleagues and lawyers, as part of ‘a sprawling hacking-for-hire operation that for years has targeted the email accounts of government officials, journalists, banks, environmental activists and other individuals.’

Collective actions that follow a strategy of attack are typically seen as spectacular interventions and so are likely to gain mass media attention. However, media reporting tends to focus on the attack itself, rather than on the message it attempts to convey, making it difficult to gain resonance among the broader public and policymakers. At the same time, attacks that disrupt users’ daily use of social media risk generating annoyance, which again may restrict the impact of the message.

Alternatives (Eroding Capitalism)

The strategy of alternatives (or eroding capitalism) entails activists building their own social media platforms or digital properties where they can network on social issues and disseminate alternative information to the public. Such platforms operate with different rules: they are often designed by advocates of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), meaning that the code is open for everyone to use, adapt and change, provided that they are not doing it for commercial reasons. Such platforms also operate with different policies regarding anonymity and privacy, in an effort to guarantee the safety of their users. Examples include the platform N-1 developed by activists in Spain right before the first stage of the Indignados movement in 2011, as well as RiseUp!, Crabgrass, and Occupii, the activist alternative to Facebook created by Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Other examples include video-streaming platforms such as BitChute (previously also Vine or Periscope) or podcast channels hosted outside the dominant commercial platforms to circumvent moderation. Activists may further use platforms like Mastodon, which is now emerging as an alternative to Twitter, that, although not explicitly developed by social movements, still operate in ways that accord with progressive values.

There are also alternatives for instant messaging or email that facilitate more secure internal organising processes for social movements. For instance, Riseup.net, an independent social network based in Seattle, has provided encrypted secure email and mailing-list management services for social movements since its inception in 1999–2000. More recently, platforms such as Signal, Telegram or GroupMe have also been used for coordination, with Telegram in particular facilitating both interpersonal and broadcast communication. Such channels are also used by environmental activists that engage in more disruptive tactics.

Social movements have also created their own platforms to disseminate information about their causes and to report on their mobilisations in an effort to tackle the marginalisation and misinformation peddled by most mainstream news outlets and social media platforms. One example is Unicorn Riot, a non-profit online news collective, which was founded in 2015 by activists who were involved in alternative media around the Occupy movement, the tar sands mobilisations, and the Ferguson protests. Unicorn Riot reported from the ground in North Dakota during the #NODAPL or Dakota Access Pipeline Protests in 2016, when different Native American tribes opposed the building of a pipeline carrying crude oil from Dakota to Illinois. Protesters considered the pipeline, which was going to pass through the Indian reservation at Standing Rock, as posing a serious hazard of water pollution. Calling themselves ‘water protectors’, activists established a protest camp in the area and attempted to stop the building of the pipeline. The mainstream news media provided little news coverage, while prominent investigative journalists, like Amy Goodman, co-founder and presenter of Democracy Now!, were arrested on riot charges. By contrast, Unicorn Riot was able to provide independent coverage of the protests, with journalists staying in the camp and interviewing protesters. The decentralised online platform is therefore a good example of the kind of community media built in the service of social movements and the continued importance of journalism produced from within activist communities.

With some notable exceptions, however, efforts to build anti-capitalist alternatives tend to be ephemeral, under-funded and unable to fully replace the services afforded by corporate social media. What these platforms also lack is ‘network effects’, a term that points to a crucial dynamic of social networks: that the more members they acquire, the more useful they become, since they can be used to communicate with a wider range of participants. In reality, many alternative platforms are used only by the converted – experienced activists who are already familiar with the mobilisations in question. Hence, by communicating solely within these spaces, activists may effectively remain invisible within a communicative niche.

Adaptation (Taming Capitalism)

The limitations of small-scale alternative platforms often lead activists to use corporate applications like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to attract a wider public. Activists thus engage in a strategy of adaptation, meaning that they adapt to the rules of corporate platforms, trying to harness their power for increasing their movement’s visibility.

Corporate social media platforms have now become key channels for publishing information about climate change. Most major activist groups and movements are using their social media accounts to disseminate information about their cause. Social media have also facilitated the rise of ‘green influencers’ – environmental activists who command very large followings on social media. Alongside them, we find collectives like EcoTok who report on environmental issues on TikTok. According to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, such channels are particularly important for users under the age of 35 who ‘are often two or three times more likely to say they pay attention to celebrities, social media personalities, or activists for climate change news than people over 35’.

There are also cases where social media channels have enabled marginalised voices to come to the fore. An example is the Digital Smoke Signals Facebook page, founded by the late Native American journalist Myron Dewey, which provided important coverage of the #NODAPL protests. The page was one of the most followed news outlets on the protests and some of its videos amassed more than 2.5 million views. Facebook live was also used to report live from the protests, allowing activists unfiltered and uncensored reporting from the ground. In the years since the Arab Spring, livestreaming has become an important application in the hands of citizen reporters. While in the 2011 wave of mobilisations, livestreaming was provided by smaller start-up companies, by the mid-2010s most major social media platforms, including Instagram and Facebook, started to offer this functionality, thus eclipsing the smaller players in the field.

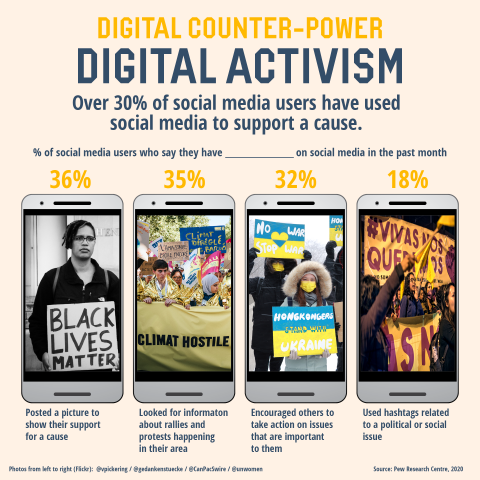

Strategies of adaptation also include the development of new approaches for engaging with the campaign targets or for demonstrating one’s support for a cause, which are tailored to the social media environment. These may include relatively ‘effortless’ acts, such as adding a banner on your profile picture on social media to show your support for an environmental cause. While such tactics are useful for gaining visibility in a crowded media landscape, they are often derided as ‘clicktivism’ – a portmanteau term that combines ‘click’ with ‘activism’. Critics point to the limited commitment needed to engage in such activism and its potential to create a misleading sense of effectiveness and connection. Yet this depends on the political context since in more restrictive and authoritarian countries a tweet or a Facebook post can easily land you in prison, or even face a death sentence. ‘Clicktivism’, in other words, depends on the eye of the beholder.

Strategies of adaptation are also associated with the emergence of new activist tactics such as Twitter storms, whereby users bombard a hashtag with tweets to make it into a trending topic. Hashtag hijacking is a variant of this tactic, where activists seize control of a target’s hashtag. Environmental activists have also pioneered the tactic of ‘greentrolling’ the social media accounts that peddle climate disinformation or engage in ‘greenwashing’. ‘Greentrolling’ is a strategy of adaptation as it is based on adopting ‘a form of rebuttal better associated with the Internet’s ne’er-do-wells — trolling — infused with voice, verve and mordant humor’. By targeting the social media of large corporations, climate activists gain a wider reach for their messages and attract mainstream media interest. A famous example came in November 2020, when Shell put up a social media poll asking users ‘what are you willing to do to reduce emissions?’. The poll received many ironic replies from environmental activists, politicians and ordinary users, including high-profile individuals such as Greta Thunberg and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who used the poll to denounce Shell’s role in increasing emissions.

Yet, to pursue strategies of adaptation, activists have to obtain intimate knowledge of how commercial social media platforms operate. This may demand greater professionalisation of activist communications, leading movements to employ social media professionals or to provide training to social media administrators, as well as to develop specific guidelines and protocols.

The adaptation strategy has several risks for progressive activists. It forces them to give up direct management of their visibility spaces as they can exercise very limited control over the materials they publish on commercial platforms or the infrastructure that enables their publication. This makes their visibility particularly fragile: if a social media outlet decides to delete a group’s profile, the entire archive of content published up to that point will probably disappear, along with the network of contacts built up through ongoing use of the platform.

Commercial social media platforms are constantly tweaking their algorithms to impede content creators from attracting wider audiences on the basis of organic reach. This allows them to charge creators for reaching their own followers with prices that are sometimes exorbitant for most activist groups. It also creates power asymmetries in activist efforts to counter disinformation. Groups that spread false information on, for instance, the role of polluters in slowing down the adoption of policies on climate change are often financed by these very polluters, capital that enables them to pay for greater reach. Social media are also exploiting the user data created by the activity of social movements on the platform. The more polarising the cause, the more profit it creates for the company as it fuels traffic and user activity. It is thus no surprise that the strategy of adaptation tends to be at odds with core values of left-leaning activist communities, such as their aversion to capitalism. In fact, the use of proprietary platforms is often at the heart of internal conflicts within activist groups, between those who support their use for pragmatic reasons and those who refuse to engage with them.

The corporate surveillance on mainstream social media also feeds into systems of state surveillance. This is the double sword of visibility, where becoming more visible on social media also makes activist groups more vulnerable to the authorities. A key strategy in this respect is to use commercial platforms to promote public events, but keep all internal organising on alternative platforms that have encrypted communication or off digital media altogether by employing the time-worn methods of secret face-to-face meetings. In other words, activist groups need to combine different strategies and platforms, depending on the tasks they need to accomplish and their associated privacy or need for greater visibility.

Moving forwards: Collaboration, Interconnectivity and Curation

Progressive social movements, and environmental activists in particular, can use different strategies for both challenging and harnessing the power of commercial social media. They can abstain, build alternatives, go on the attack and adapt. Each has advantages and drawbacks in terms of effectiveness and impact, and depends on context. In practice, activists often deploy some or all forms.

In other words, the four types of strategies outlined in Rucht’s ‘Quadruple A’ work better in combination rather than separately. Yet, it is exactly this art of pursuing different strategies simultaneously that is the most formidable. What should be the balance between challenging corporate platforms but at the same time harnessing their power? And can one group do all this alone or should it work in coalition, so that it can specialise in specific strategies?

In this respect, working collaboratively seems to be the way forward. This may take the form of more formal coalitions and umbrella platforms or happen more informally through the development of common themes in campaigns, the exchange of resources, as well as sharing each other’s content and creating more densely hyperlinked communication properties. Environmental groups, for example have also begun to work in a more intersectional manner by considering the issues on which they campaign from the perspectives of different stakeholders and by mapping the interlocking systems of power that need to be overcome. Such collaboration and coalition-making need to be reflected more strongly in the digital realm, with greater hyperlinking and interconnectivity among environmental groups, whether via social media accounts on commercial platforms or alternative media outlets. In this respect, studies on video activism around climate justice and social justice movements in the early 2010s showed very weak connections between actors on YouTube. The actions and actors within social justice movements were largely disconnected – or at least they were not coming together in any meaningful way on that particular platform. Thus, as a potential site of resistance YouTube failed to provide a space for sustainable, horizontal, and radical media practices.

This seems to ring even truer today – a decade on and in a context where YouTube is mainly discussed in terms of rabbit holes, radicalisation and disinformation rather than democratic broadcasting, visual evidence and radical eye-witnessing. When there is evidence to suggest that a network of connective actions is in fact materialising, the process is led by anti-democratic and far-right reactionary forces. They have largely succeeded in connecting across party lines and intra-movement differences, building a sizable audience, and forming a coherent web of related channels and content which extend into a larger media ecology of alternative far-right media. They do this through an interlocking series of connective practices including guest appearances on each other’s YouTube channels, joint livestreaming, as well as various referencing and hyperlinking practices.

Even when the right have been deplatformed, for example in the wake of The Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, far-right groups have migrated to Alt-Tech platforms that are harder to control, including Gab, Parler, Gettr, BitChute, Rumble, PewTube, Odysee, Hatreon and numerous others. These have been designed following the models of Big Tech platforms and mimic their features while also offering anonymity and far fewer restrictions on the level of offensive and harmful material that can be posted.

The far right has been very able to engage on a wide range of platforms at the same time and for different purposes – combining alternative and mainstream – while deliberately adopting a different tone for different platforms with some degree of success. It helps, of course, that in comparison to progressive movements, far-right activists have fewer scruples in using a more offensive, irreverent and populist tone that does well on social media in terms of virality and algorithmic optimisation. The far right is also less reluctant to use commercial and profit-driven platforms, and has found ways of monetising its content by interspersing business strategies with political propaganda techniques.

Far-right activists have thus built an ecosystem of Alt-Tech platforms that has outdistanced progressive alternative media in terms of crowdsourcing and successful fundraising for tech start-ups. Of course, the recent success of the far right has resulted not only from savvy social media strategies, but also from a broader political context that is conducive to its goals. After the repression – and, in some quarters, perceived failure – of the 2011 progressive movements, some of the same anger towards the establishment has been harnessed by reactionary, conservative actors. Far-right activists have thus made the most of the opportunities that come with being in line with broader political currents and particularly the rise in the politics of fear that go along with uncertainty and increasing inequality. Yet, the perfect storm of economic, social and climate crises that we are currently facing is also presenting an opening for radical change on the progressive side of the political spectrum. Developing greater connectivity across groups, issues and digital media properties is paramount within this context.

Apart from hyperlinking and interconnectivity, consistency and continuity will also help progressive groups, and the environmental movement in particular, in harnessing digital power. Lasting bonds of collaboration can alleviate the immense efforts of voluntary labour for establishing and running alternative platforms through the development of routines and a repository of knowledge and experience. Such labour is also necessary for attacking commercial social media, which is often based on the painstaking collection of information about the profit-driven logics of Big Tech. Sustained collaboration over a period of time makes this voluntary labour possible as it enables knowledge transfer across different activist groups and generations, gathering insights from past experiences, from what works and what doesn’t, and ensuring that these lessons are passed on and combined with new insights for new generations of activism.

As demonstrated by the example of the far right, the curation of digital content is another crucial aspect of interconnectivity and collaboration. Curation refers to the process of finding, selecting, organising, and interlinking suitable messages. It thus helps to create a collaborative network of interconnected actors and communications that provides a rich and consistent message and offers users different entry points to the ‘message space’ of progressive movements. At its core, curation is all about the cultivation of community, connectivity and participation, a logic that goes against social media business models which foster individualism and the personalisation of political action.

Obviously, such strategies of collaboration often encounter many obstacles. Doctrinal and ideological differences, however minute they may seem to outsiders, may split progressive movements and increase factionalism. Greater collaboration can pose risks to legitimacy, as groups may be afraid to align more closely with, for instance, a more radical actor, since they can be tainted by association. Or the reason may be more self-interested, as groups may want to retain audiences in their own social media properties rather than sharing them with related actors. The lack of funding and resources for progressive politics may lead to competing for audiences and a lack of connectivity between activist groups online.

Thus, for collaboration to work, activists need to be committed to working together in providing alternatives. Moving ahead, it is this belief in the value of building broader networks of networks that can help activists in harnessing the power of digital media, resisting Big Tech and changing the world.