The Referendum in Ecuador Article 422 of the Constitution resists

Regiones

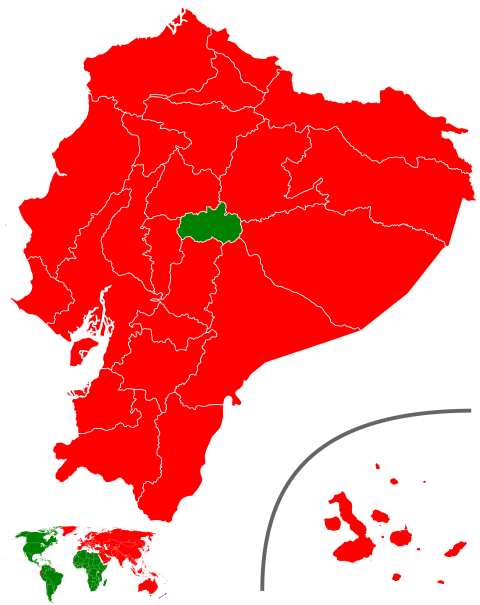

The people of Ecuador voted against proposals put forward by Ecuador’s president, Daniel Noboa, in a referendum on calling a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution, allowing foreign military bases, reducing the number of members of the National Assembly and eliminating public funding for political parties.

For Noboa, who had been re-elected in April until 2029 with a landslide victory, this was a major setback. What was expected to be a celebration for the governing party at the beginning of the day ended up being one for the opposition. Luciana Ghiotto, Doctor in Social Sciences (UBA) specializing in trade and investment agreements, highlights one important result of the referendum: another NO to the investment protection regime.

Rodolfo Matias, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

On 16 November 2025, the people of Ecuador went to the urns to voice their opinions in a referendum called by President Daniel Noboa. Four questions were put to voters: permit foreign military bases on national territory (eliminating the ban in article 5 of the Constitution), end state funding for political parties, reduce the number of National Assembly members from 151 to 73 and hold a Constituent Assembly to draw up a new constitution.

The results were clear: the “NO” won in all four questions. The main question, on the convocation of a Constituent Assembly, was rejected by 61.39% of voters. This represents a historic victory for the defence of the Constitution of Montecristi of 2008 and, with it, article 422, which prohibits international arbitration in disputes with foreign investors.

The most advanced constitution in the world under systematic attack

For more than a decade, the economic right has systematically attacked the Constitution of 2008, considered the most advanced in the world in matters of human rights, the rights of nature and collective rights. The Constitution, with its 444 articles, broke with the traditional approach that prioritizes some rights over others, as it recognizes all rights as interdependent and of equal status.

Among its historical innovations, the Constitution of Montecristi was the first in the world to recognize the rights of nature and rivers as subjects of rights. It enshrined sumak kawsay (the good life) as a guiding principle and established Ecuador as a plurinational and intercultural state. It was also a pioneer in Latin America as it included 58 articles on human mobility, taking a comprehensive rights-based approach to emigration, immigration, refuge, asylum and internal displacement. In addition, it guaranteed the human right to water as a fundamental and inalienable right and strengthened the collective rights of Indigenous peoples and nationalities.

President Noboa had declared his intention to reduce the constitution to 180 articles, although he never presented a concrete reform programme or plan. The proposal to hold a constituent process was to be a “blank cheque” to dismantle the rights framework won in 2008. Alberto Acosta, the president of the Constituent Assembly of Montecristi, warned that the real goal was “to further consolidate the personal power of a ruler” and “favour the elites and foreign interests”, especially in relation to the overprotection of foreign investors and the elimination of prior, free and informed environmental consultations.1

The Constitution of Montecristi was elaborated with the active participation of a wide range of sectors of society, which is a departure from the Ecuadorian constitutional tradition of drafting texts with little popular participation. As Acosta points out, this Constitution is unique for being “the only one approved in a referendum after a genuine constituent process” in the history of Ecuador.

Article 422: a padlock against transnational corporate power

The attacks on the Constitution have mainly targeted article 422, which stipulates that:

“Treaties or international instruments where the Ecuadorian State yields its sovereign jurisdiction to international arbitration entities in disputes involving contracts or trade between the State and natural persons or legal entities cannot be entered into.”

This article arose from Ecuador’s traumatic experience with international arbitration. The country has faced devastating cases such as the one of Occidental Petroleum (in which Ecuador was condemned to pay out US$1.77 billion) and the one involving Chevron. In 2018, an international arbitration tribunal overturned the ruling of Ecuadorian courts that had ordered Chevron to pay US$9.5 billion for contaminating the Amazon for decades. Article 422 was the Constituent Assembly’s response to these predatory arbitration cases: it aims to prevent transnational corporations from circumventing Ecuador’s courts and going to private international tribunals to penalize the state.

Article 422 is key to the right’s proposal for the international integration of Ecuador: to have an influx of large extractivist corporations that will operate in the territory free from state control. Rejoining the investment protection system would mean total freedom for investors and that the state would have no capacity to guide these investments towards development objectives. The elimination of article 422 would consolidate Ecuador as an oil, mining and raw materials supplier subordinated to transnational extractivist interests.

Ecuador does not forget: 29 lawsuits and 3 billion paid in arbitration

Ecuador has proven experience in saying “no" to arbitration and corporate privileges. This is not the people of Ecuador’s first victory in their defence of article 422. In April 2024, in another referendum, 64.88% of the population voted “NO” to modifying article 422. Ecuador has a long history of resistance to arbitration, which led to its explicit prohibition in the Constitution of 2008 and that the recent popular victory reaffirms.

To understand this ongoing resistance, one must first comprehend what the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) system is. This mechanism is contained in investment protection treaties and gives foreign corporations the right to sue the Government of Ecuador in private international tribunals when they believe that their expected profits have been affected by public policies. Contrary to ordinary justice, this system allows foreign investors to bypass national courts and access private, parallel and privileged judicial channels.2 The arbitrators in these tribunals are not independent judges, but private lawyers who charge million-dollar fees for each case, which generates serious problems of conflict of interest and lack of transparency and impartiality. Moreover, the rulings (called “awards”) are final, there is no appeal mechanism and states are forced to pay the compensation ordered.

This mechanism also has a chilling effect on public policies: states refrain from introducing necessary environmental, labour or social regulations for fear of being sued under these treaties. What is more, the sunset clauses in these treaties allow investors to file claims up to 10 to 15 years after the country has terminated the treaty. This explains why even though Ecuador ended all its bilateral investment treaties in 2017, it can still be sued until 2027-2033. At the international level, ISDS arbitration has drawn major criticism in academic, government and civil society circles, which question it for its antidemocratic nature and for favouring corporate interests over the rights of communities and environmental protection.

Ecuador knows about these costs from its own experience. The country has faced 29 international arbitration lawsuits, making it the fifth most sued country in Latin America. Half of them is linked to activities in extractive sectors. Arbitration cases have already cost the Ecuadorian state close to US$3 billion. US investors registered seventeen of the 29 claims or almost 60% of the total.3 This traumatic experience with the ISDS system explains the wisdom of the people of Ecuador in saying no to extractivism and corporate power, built and reaffirmed through multiple popular consultations:

- The consultation on the Yasuní (2023), in which 59% of Ecuadorians voted “YES” to keep the oil of block 43 (Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini, ITT) indefinitely in the ground of the Yasuní National Park, one of the most biodiverse areas on the planet. This decision obliged the government to dismantle all oil operations in the area within one year.

- The consultation in Cuenca (2021), where 80% of voters said “YES” to banning large-scale metal mining in several rivers’ water recharge areas and where popular resistance to a Canadian mining corporation in the páramo of Quimsacocha is still strong today.4

- The April 2024 referendum, where 64.88% of the population voted “NO” to amendments to article 422, thus refusing to allow the Government of Ecuador to recognize international arbitration as a method for solving investment disputes.5

- And now, the November 2025 referendum, where they rejected the proposal of a Constituent Assembly, which would have opened the door to the dismantling of these protections.

This popular resistance received institutional support in 2017, when, based on the findings of the Commission for a Comprehensive Citizens’ Audit of Reciprocal Investment Protection Treaties (CAITISA), the Rafael Correa administration terminated all investment protection agreements that contained arbitration. The CAITISA demonstrated that Ecuador does not need investment treaties with arbitration to attract investment: most investments had been from countries with which Ecuador does not have investment treaties, such as Brazil, Mexico and Panama.6 This decision was fundamental in reinforcing the legal padlock that the Constituent Assembly of Montecristi had built into article 422.

This legal barrier has, however, been systematically attacked. The governments of Lenin Moreno, Guillermo Lasso and Daniel Noboa have tried to knock it down in different ways. Moreno attempted to reactivate investment treaties and proposed that disputes could be resolved in regional arbitration centres (in Latin America) instead of the ICSID. He also suggested signing 16 new investment protection treaties. Lasso had Ecuador rejoin the ICSID in 2021 and signed a treaty with Costa Rica (which the Constitutional Court later declared unconstitutional precisely because it included ISDS). Noboa, for his part, sought to give the green light to arbitration through the 2024 referendum and tried to call a Constituent Assembly to eliminate this protection and negotiate contracts with Canadian mining corporations that contain the ISDS mechanism.7 The trade agreement that Noboa reached with Canada in February 2025 follows along the same lines: this treaty incorporates international arbitration, in direct violation of article 422, and has been specifically designed to protect Canadian mining investments.

The strength of the constitutional design and popular resistance have succeeded in holding up this barrier to international arbitration. However, the battle is not over. It now remains to be seen if the government will respect the will of the citizenry or continue attacking article 422. The treaty with Costa Rica remains paralyzed, and the one with Canada, virtually frozen. Organized popular forces are needed to protect the Constitution and article 422 from the blows that will surely continue.