Waging counterinsurgency How to dismantle the US coercive apparatus

Temas

Regiones

The constant waging of counterinsurgency by the US both domestically and on foreign soil has served as the basis of exchange among the institutions of the US and, eventually, the global coercive apparatus.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/expertinfantry/ (CC by 2.0)

On 1 May 2003, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, President George W. Bush declared victory in Iraq. This optimism proved to be premature. In early 2007, General David Petraeus assumed command of the US forces in Iraq to salvage that ‘victory’ after the world’s greatest military power had struggled to quell Iraqi opposition to what had become a US occupation. Iraqi resistance was cast as an insurgency and Petraeus highlighted the ‘innovative’ strategy to combat it in a memo entitled ‘Counterinsurgency’.

The US amnesia regarding its ‘new approach’ in Iraq is truly remarkable; but then the US historical narrative about its own policing and military forces is also fractured and disjointed. The official version of US history obscures the common thread of civilian-focused, irregular warfare, known as counterinsurgency (COIN), that runs through the country’s coercive apparatus from before its independence to the present day. Coercive apparatus refers to the range of institutions engaged in a state’s policing and military capabilities at home and abroad.

Counterinsurgency is understood by its implementors in purely negative terms: eliminating or subduing an insurgency, which is defined as ‘a revolt against a government, not reaching the proportions of an organized revolution; and not recognized as belligerency’.1 Unlike conventional battle, this form of warfare recognizes that the insurgent claim is fundamentally political and, therefore, attempts to engage the enemy on primarily non-military terrain. As a result, counterinsurgency tactics are conceived in very broad terms, encompassing, political, economic, military, paramilitary, psychological and civic actions.2 Over time, COIN has been described by a host of names, including ‘irregular’, ‘guerrilla’, ‘winning hearts and minds, ‘unconventional’, ‘total’, ‘low-intensity’ or ‘special operations’ warfare.

In all, the negative definition, tactical diversity and range of pseudonyms contribute to a muddled and imprecise conception of COIN. This conceptual ambiguity combined with the array of contexts across time and space where it has been utilized has given counterinsurgency a powerful mystique: sufficiently dynamic and malleable to allure its advocates yet nebulous enough to elude those trying to explicate its repeating patterns of violence.

Here, I will argue that counterinsurgency can be understood in more concrete and practical terms. Rather than defining it against insurgency, a nebulous concept itself, I consider COIN’s central aim and strategic approach: a form of warfare designed to combat primarily political not military threats through a tactical repertoire that targets civilians and their livelihoods. Conceiving of COIN in this way helps establish an initial foundation for building a more comprehensive interpretive framework. This framework is further enriched by situating COIN’s legacy in the historical record and by incorporating the experiences of its targets, everyday marginalized people.

The constant waging of counterinsurgency both domestically and on foreign soil has served as the basis of exchange among the institutions of the US and, eventually, the global coercive apparatus. When the US emerged from World War II as the dominant world power, it needed to develop a form of control far less overt and direct than the European colonialism of the previous centuries. In order to wield this power under the guise of respecting political and human rights and propelled by a rapidly advancing military-industrial complex, it exported its model of population-centred warfare to police forces around the world. As a result, much of the global coercive apparatus can be viewed today as a descendent in the genealogy of what the US military scholar John Grenier has termed America’s ‘first way of war’.

Understanding the relentless pursuit of counterinsurgency helps us to see the US national project from its settler colonial beginning to its contemporary status as global hegemon as coherent and consistent. This further reveals the historical continuity among the state’s coercive institutions from its settler militias, slave patrols and early imperial army to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), militarised police forces and a modern, professional occupation-style military.

Comprehending the historical and geographical pervasiveness of counterinsurgency in the coercive branch of US empire serves not only to interpret the past more accurately. This reconceptualisation of how we understand the structure of state violence is also instructive for contemporary social and political movements around the globe looking to dismantle it.

Counterinsurgency’s Contradiction

The labelling of enemy combatants as an insurgency is intentional, and its logic has a very specific purpose. Returning to the definition, insurgency is waged against a government, but does not reach the threshold of an organised revolutionary movement and so is not entitled to the normal privileges and legal conventions of battle. In other words, it is a militant adversary that is viewed as an unorganised, illegitimate challenger to an assumed legitimate entity in the form of a government.

As the prescient scholar of counterinsurgency Eqbal Ahmad noted, ‘The opposite is true: counterinsurgency involves a multifaceted assault against organized revolution….It serves…to relegate revolutionaries to the status of outlaws…constitut[ing] an a priori denial of legitimacy’.3 Ahmad’s observation is incisive and illuminates a key characteristic of counterinsurgency contexts: the very legitimacy of these operations is contingent upon its adversary waging what the government authorities view as an illegitimate struggle.

Thus, the logic of counterinsurgency, taken at face value, is contradictory. It is a strategy that purports to be political in nature, as it attempts to win ‘hearts and minds’, yet its very foundation requires the negation of the political claim of the ‘insurgents’. This renders the political ‘battlefield’ zero-sum terrain, whereby counterinsurgents central aim becomes smothering political imagination into acceptance of the status quo or advancing a counter-revolutionary cause.

Tactically speaking, the strength of COIN is supposed to be its adaptiveness or the ability to wage war in such a way that remains contextually appropriate. However, its inherent political rigidity leads to an obsession with order, control, obedience and stability over participation, consent and change that makes people the objects of policy in such a way that renders the incorporation of contextually specific and well-intentioned tactics irrelevant. 4

These fundamental contradictions are further realized through an investigation of the historical contexts where COIN has been waged most formatively. US counterinsurgency refined its art in waging war against indigenous resistance to settler colonialism, Black Liberation, leftist movements and anti-colonial forces fighting for self-determination. While the US government has largely been effective in framing each of these liberation struggles within the definitional bounds of insurgency by connecting them to seemingly isolated instances of existential threat, the historical record reveals a coherent line connecting its settler colonial genocide to its current conquest and occupation of countries in the Middle East, as it had previously done in Latin America and the Caribbean.

By ensuring that the historical narrative of the US coercive apparatus continues to be disjunctive, such that the repeating patterns of COIN violence are sufficiently obscured, the political project of domination that lies at the heart of US empire remains elusive. This results in a collective amnesia, which helps to explain why, in mainstream historical narratives, the brutality of the Vietnam war is considered an aberration, the origin of police as slave patrols is largely forgotten and the constant erasure endured by Native Americans remains relegated to the periphery. Through a historic lens, though, the similarities of early settler militias and modern SWAT teams, scalping bounties and privatised military forces as well as slave patrols and racialised police brutality become apparent - the real differences lie only in standards of professionalisation and technological advancement.

A genealogy of US counterinsurgency

The antecedents of modern US counterinsurgency predate the country’s independence by over 150 years, making this method the most central feature of US warmongering throughout its history. The following genealogy highlights four crucial periods in the over 400-year history of war waged against civilian populations: settler colonialism and slave patrols; expansionary imperial wars, early policing and Jim Crow; Cold War campaigns following the Second World War to counter decolonisation, civil rights and leftist movements; and finally, today’s modern apparatus of militarised police, mass surveillance and an occupation-style military.

Each of these periods has played a role in advancing specific aspects of US counterinsurgency although it has always remained true to its foundation: waging war against people and their livelihoods, painting each threat as illegitimate and existential and using the guise of new technology and professionalisation to inflict brutality upon civilian populations. In no period has there been any clear distinction between the domestic and foreign application of counterinsurgency. The marginalised within the US have suffered immense horrors as have poor and marginalised civilians around the world, each serving as a testing ground in the development of new methods to terrorise ‘the Other’.

Settler colonialism and slave patrols

According to the founding US mythology, indigenous peoples tragically disappeared because they had no immunity to European diseases, a handful of skirmishes with early settlers and a few instances of unfortunate brutality. While large numbers of Native Americans did perish from disease, a concerted genocidal campaign of ruthless decentralised war was waged on indigenous peoples and their way of life. This early strand of counterinsurgency was initially developed by settlers in response to the inadequacy of traditional European military practices for fighting off indigenous forces.

John Grenier describes ‘a war tradition that saw nonprofessional soldiers pursue unlimited objectives, often through irregular means’,5 such as destroying villages and food supplies, killing non-combatants, assassinating leaders and using captives as scouts.6 He asserts that the colonists would have struggled to defeat the fierce indigenous resistance had they not continued to develop a coherent strategy around three central pillars: the furtherance of unlimited or total war; the creation of special forces, known as rangers, used to penetrate and harass indigenous groups deep in their territory; and finally, the privatisation of the war effort, in the form of scalping bounties, to mobilise the civilian population with economic incentives.7

These factors ensured the settler colonial project remained appropriately ruthless in order to pursue its agenda of conquest and erasure. While the horrors of this early form of war are deliberately obscured to preserve a sense of colonial victimhood and exceptionalism, its remnants have seeped deep into American culture. The professional baseball team in Texas is still called the ‘Rangers’, children are often taught (as I was) that scalping was an indigenous practice, and the military still uses the term ‘Indian country’ to designate enemy territory during operations.8

While the indigenous threat to the colonists on the frontier was viewed in ‘foreign’ or ‘external’ terms, the more widely known introduction of chattel slavery following their arrival provided a sufficient internal threat to ensure the development of the other side of early counterinsurgency tactics: policing. The US colonial experience in the southern states was defined by slave populations outnumbering white settlers, making a regime of surveillance and terror instrumental to ensuring the survival of slavery.

Not unlike settler militias in their justifications for and ways of prosecuting war, slave patrols developed as groups of citizens who, as part of exercising their civic duty and enjoying legal protections, enforced the institution of slavery through physical and psychological brutality. These two strands of early American counterinsurgency merged during ranger missions deep into Florida (after 1623 slaves could gain freedom by reaching Spanish territory), commonly used to retrieve escaped slaves and terrorise indigenous communities protecting them. These early antecedents of policing and war-making serve as the foundational moments of US counterinsurgency.

Formalising counterinsurgency: Imperial conquest and racial apartheid

Total war’, a euphemism for counterinsurgency, was a strategy used by both sides in the American Civil War, playing a key role in General Sherman’s ‘March to the sea’ that secured the Union victory. The next essential piece in this genealogy, however, took place on the other side of the world, with the US conquest of the Philippines in 1898. Despite the US amnesia about rampant irregular warfare in its own territory, the colonial conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish–American war is remembered as a success and has been a frequently cited case for subsequent operations.

The Spanish–American war began when the weakening Spanish empire was struggling to retain its colonial possessions. In an effort to save face in the Philippines, the Spanish and Americans held a staged battle, with the Spanish surrendering to the US forces, even though the decades-long independence movement led by Emilio Aguinaldo was the greatest reason for Spanish attrition. After promising independence to the Filipinos, the US soon reneged on its promise and occupied Manila, declaring the whole of the Philippines an American possession.9 In the first week of 1899, Aguinaldo denounced the US proclamation, triggering what is often referred to as the ‘Philippine Insurrection’.

Over the course of the next 13 years, but particularly intensely during the following three years, the US army launched a brutal counterinsurgency campaign after struggling to defeat Aguinaldo and his forces’ guerrilla tactics. The US response took on a familiar form: the use of torture, especially waterboarding; large-scale extrajudicial killings; forced starvation by destroying vital food sources; and massive displacement into concentration-style camps.10 It is estimated that 20% of the Filipino population was killed during the campaign.11

The similarities to the ongoing settler colonial genocide at home were not coincidental. 26 of the 30 generals who served in the Philippines were officers in the so-called ‘Indian Wars’, one of whom had fought alongside General Custer and another who had falsely gained notoriety for capturing Geronimo.12 In an even clearer connection between the two contexts, the admiral in charge of the re-colonisation of the Philippines, George Dewey, actually referred to the Filipinos as ‘Indians’.13 The ‘success’ of the Philippine–American war consolidated what had been America’s ‘first way of war’ as its main tool of foreign conquest.

The campaign in the US was no less horrific. Despite the conclusion of the Civil War formally ending slavery and the legal protections afforded to slave patrols, the same activities were picked up by white economic associations, rifle clubs and vigilante groups, of which the Klu Klux Klan was the most powerful.14 The main enforcer of Reconstruction 15 was the occupying Northern army, which only did so haphazardly and was soon removed in 1877 by President Hayes, whose promise to do so had secured his election victory in 1876. This inaugurated the Jim Crow era, when overtly segregationist laws, upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896, the violent removal of elected Black officials, and widespread lynchings constituted a reign of terror that enforced a system of racial apartheid until the 1960s.

This same era is characterised by the formal bureaucratisation of domestic counterinsurgency operations in the form of police departments. By the 1880s, all major US cities had established these, creating a paradigm shift from policing as a reactive decentralised enterprise to a centralised one 16 focused on ‘preventive’ measures to ensure order.17 This approach placed a particular emphasis on surveillance, large-scale arrests and the use of extreme violence against the ‘dangerous classes’freed blacks, poor whites and immigrants.18 The parallels between the methods being used at home and abroad were not coincidental and the connection was not lost upon those implementing them. In 1905, the Pennsylvania State Police were modelled directly on the Philippine Constabulary, the colonial occupation force throughout the islands.19

Empire politics: COIN as policing

The US emerged from the two biggest conventional military endeavours in its modern history, the First and Second World Wars, as the world’s dominant economic and military power. This coincided with the era of decolonisation and the onset of the Cold War, meaning the US needed to find a way to assert and legitimise a new anti-communist global empire while plausibly claiming to champion self-determination. This rationale had to be established and applied on both the domestic and foreign fronts, because direct interventions by US troops and the legally upheld racial caste system at home were simultaneously tarnishing its image.

The Cold War era ushered in an immense expansion of the US military’s technical capacity and geographic reach leading to interventions around the globe – Korea, Vietnam, Nicaragua, Chile, Iran, to name a few. While these operations are considered cornerstones of US Cold War policy, it was not lost upon certain US officials that they did more to alienate than attract the emerging Third World. These policymakers believed that US hegemony could be advanced without compromising its image and that military intervention should serve as a back-up to a more subtle, preemptive form of warfare. These officials’ approach was far from new, and, instead, borrowed heavily from the US’s trusted playbook of COIN but adapted to the contemporary context, this time with a particular emphasis on policing.

In his 2019 book, Badges Without Borders, Stuart Schrader provides immense detail on how the US transformed and implemented its counterinsurgency agenda through ‘policing’. This would help the US combat the image of its empire on both fronts: reforming policing at home, to ensure that it became nominally divorced from racial apartheid, and training police abroad, so that foreign interventions were carried out by native soldiers in police uniforms.

Domestically, reforms largely entailed professionalising policing – essentially separating the institution from its overtly political origins and patronage systems – and modernising the police forces through the use of new technology that enhanced communication and surveillance capabilities across different police forces. These ideas and practices were exported in the form of training programmes supported and conducted by various institutions such as USAID through the Office of Public Safety (OPS), the International Police Academy (IPA), the CIA, Army and the FBI.

Tracing the origins of this transnational project further reveals the constant thread of evolving counterinsurgency and the fluid boundary between domestic and foreign practices. Many early twentieth-century police reforms were initiated by individuals who had served in the Philippines. After the Second World War, the occupations of Japan and Germany served as the principal models, but further inspiration was derived from each context where it was subsequently implemented.

Schrader makes it clear that this two-pronged approach was not only happening simultaneously but continued to evolve in tandem due to the exchange of information between institutions and a revolving door of individuals waging counterinsurgency at home and abroad. The first director of OPS, and arguably the most influential advocate of ‘counterinsurgency as policing’, Byron Engle, cut his teeth training police in Kansas City, Japan and Turkey.20 Years after OPS had been disbanded because of its connection with atrocities around the world, Engle referred to the occupation of Japan as ‘the best laboratory’, where he realised that ‘law enforcement was the leading edge of state power’.21

The effects of Engle and his cadre’s initiative through the height of the Cold War should not be underrated. With Engle estimating that OPS training programmes reached 1.5 million police officers around the world, the Army adding an additional 500,000 and the IPA graduating another 5,000 officers, it is hard to overstate the scale of the influence, especially since these are just three agencies within a larger network of institutions involved.22 Moreover, these numbers concern only the immediate effects and not the deep institutional legacies and cultures that were created around the world.

The manifestations of this global initiative led to many of the most abhorrent periods of the Cold War. The atrocities committed in the US counterinsurgency effort in Vietnam are well documented, while the FBI’s counterintelligence programme –COINTELPRO23 – surveilled, arrested and assassinated countless Black Liberation, left-wing and indigenous revolutionaries. Abroad, the effects of the trainings were particularly grotesque in Indonesia, the first country given police assistance, where over one million communists are believed to have been killed under Sukarno, as well as across Latin America, where the practice of ‘disappearing’ people first started in Venezuela, a country receiving OPS assistance, 24 and was then ‘perfected’ as it spread across Argentina, Chile and Central America.

Modern US counterinsurgency

The period since 2000 has seen the modern iteration of US counterinsurgency on full display. Abroad, unending wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been waged in the name of combatting the amorphous and existential threat of terrorism. In Afghanistan, the US has failed to defeat the Taliban, a Pashtun fundamentalist sect of the Mujahadeen, to which the US had previously channelled exorbitant amounts of money and weapons via the refugee camps in Pakistan throughout the 1980s.

In Iraq, the quickly declared victory has become an extended US occupation that has relied on a concerted counterinsurgency effort, as highlighted by Gen. Petraeus, in order to maintain the illusion of control. This effort has increasingly relied on private military mercenaries and contractors, ensuring that the counterinsurgency brutality is properly insulated from any modicum of democratic accountability. This was exemplified in late December 2020, when the outgoing President Trump pardoned four Blackwater contractors convicted of carrying out the 2007 Nisour Square massacre.25 At home, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests of 2014–2015 and 2020 are responses to centuries of racialised apartheid experienced through the lens of counterinsurgency’s most recent morbid symptoms: militarised police, mass surveillance and, as always, gratuitous violence.

Starting in the late 1960s, surplus military gear began to be channelled to local police departments. Increasing over the subsequent decades, this pipeline was made far more direct under the 1997 National Defense Authorization Act, which created the 1033 program26 allowing the Department of Defense to shed its excess equipment to law enforcement. Famously revealed to the world during the 2014 Ferguson protests, tanks, grenade launchers and other military-grade equipment are now pervasive in US policing.

Surveillance remains an integral and increasingly important part of modern counterinsurgency. Modern technology, such as facial recognition software and boundless smartphone data, has bolstered the capabilities of this arm of the coercive apparatus. As revealed by Edward Snowden in 2013, the National Security Agency (NSA), among other institutions, actively and illegally monitors and collects the data of citizens, major internet providers and world leaders.27 While it requires little imagination to conceive how this can be used, the decade-long surveillance of Muslims by the New York Police Department (NYPD) provides a clear example of the contexts where it has and will be implemented.28

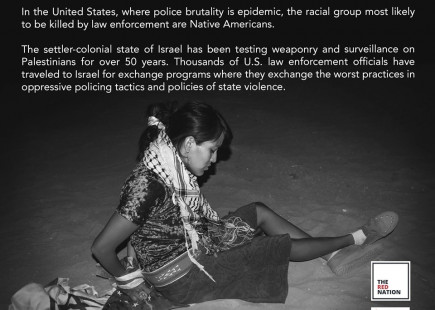

Finally, in a depraved alliance of settler colonial nations, the US has turned to importing practices from Israel. U.S. police departments are sent to learn ‘counter-terrorism’ from Israel’s military and intelligence forces in the West Bank and Gaza,29 where apartheid, occupation and dispossession are constantly being perfected in the twenty-first century. The powerful exchange of solidarity and advice between Palestinians and Black activists during demonstrations against brutality by heavily armed police in Ferguson in 2014 exemplified these parallels, showing just how tangible and relevant they are.30

COIN: Constantly Innovating but Never changing

While the core motivations, tactics and goals of counterinsurgency throughout history have remained the same, there is a constant compulsion to innovate and repackage it. Reforms have almost always, but particularly in the twentieth century, centred around professionalisation and modernisation. The two often go hand in hand and, in practice, cannot be fully separated.

Generally speaking, professionalisation involves the use of objective criteria, such as standards, metrics and systematic routines, in order to ensure a minimum acceptable level of qualification for a given task. Modernisation, especially in the counterinsurgency context, involves the incorporation of new technologies that promise to improve the execution of that task. Innovations such as the two-way radio, patrol cruiser, 911 system, tear gas, ‘stop and frisk’ and ‘broken windows policing’ have all emerged from these reform processes.

On the surface, professionalisation and modernisation appear to be constructive practices – and that is precisely the point. Each of these ‘reform’ strategies is politically expedient for the survival of institutions that have often come under intense scrutiny, and for good reasons. They are practices that quite literally justify and self-perpetuate themselves by failing. Excessive violence, among other shortcomings common to counterinsurgency, logically creates the need for more training and new technological developments.

Due to its purported embrace of politics and tactical flexibility, the pursuit of counterinsurgency will continue to be alluring to those interested in upholding the status quo. The promises of reform through professionalization and modernization create the illusion of change while always failing to disrupt its fundamental nature.

Combatting counterinsurgency: Empowering social movements

For the world’s marginalised, the counterinsurgency agenda is neither abstract nor obscure but is an everyday lived reality. The constant surveillance, harassment, and killing are grotesque manifestations of bigger social and political projects of domination: capitalism, fascism and imperialism. The coercive apparatus is the corporal enforcement mechanism through which these oppressive structures are maintained. Dismantling the global counterinsurgency agenda has to be an essential element in the pursuit of a more comprehensive emancipatory vision.

The struggles seeking to overturn the current global coercive apparatus are highly unbalanced. Those in power, regardless of political ideology, benefit enormously from the order it sustains. While these same individuals package various ‘reformist’ agendas as crisis-management tools, social and political liberation movements have been and continue to be the vanguard of substantive reimagination and transformative change.

The question, then, is how reconceptualising the US and contemporary global coercive apparatus as a form of counterinsurgency warfare can inform emancipatory political and social movements. Just as applying the framework of counterinsurgency can help explain the historical and institutional legacies of the coercive apparatus, it also helps shed further light on many well-studied aspects of social and political movement theory and practice. The counterinsurgency lens makes three of these particularly salient:

1. A globalised movement

The realities of the US empire following the Second World War have meant that its own expertise in population-based control tactics have become the model for much of the world. For social movements, this increasingly means that international solidarity, cross-movement information sharing, and globalised initiatives are more important and relevant than ever.

Solidarity remains at the heart of articulating a global struggle. For many, the concept may feel intangible and rely too much on lofty ideals such as a universal concept of what it means to be human, and a willingness to see the suffering of others as collectively detrimental. These are indeed important components of building a deeply interconnected emancipatory movement. But for anyone who finds it hard to see such interrelatedness in the abstract, the use by the most powerful of counterinsurgency across history and geography illustrates a far more concrete and direct connection among so many contemporary struggles. The elite concentration of wealth, the destruction of the world’s natural ecosystem, and the insidious violence of racism and imperialism everywhere are all enforced using the same tactics.

Studying and understanding the history of the counterinsurgency doctrine and its pervasiveness will be crucial to the success of emancipatory movements.

- The primacy of the political

Movements are by their very nature political: they involve advocating for the interests of groups and people by navigating the avenues of power and confronting them. Conversely, counterinsurgency behaves paradoxically by trying to embrace the political nature of conflict while hinging its own legitimacy on rejecting the opposing political claim. The zero-sum nature of the political terrain that counterinsurgency requires is in fact its greatest point of vulnerability: if the ‘insurgency’ gains legitimacy, then the counterinsurgency must lose it.

Exploiting this contradiction and targeting it as an area of weakness needs to be a central focus of movements’ strategic repertoires. In order to do this effectively, movements must wage the struggle where they are strongest – on the political terrain. This is particularly clear when trying to overpower the coercive apparatus with force, which is evidently quite delusional.

Rather, moral isolation and flipping the switch of legitimacy become central. Confrontational tactics remain essential, but only insofar as they help to outflank the opposition politically. To invoke Eqbal Ahmad again, ‘the major task of the movement is not to outfight but to out-administer the government’.31 Ironically, movements must achieve what counterinsurgency purports to do but is inherently unable to achieve: ensure the primacy of the political.

- Centering popular resistance

Popular resistance, sometimes referred to as nonviolent resistance, lends itself to political struggles characterised by large asymmetries of power. It is a strategic repertoire based on the view that power relies on multifarious levels of consent. Waging a successful struggle means undermining these systems of power by withdrawing the everyday forms of consent that are fundamental to their persistence.

This is particularly salient in the counterinsurgency context, where attempting to outfight the coercive apparatus through violent means is an unwise strategy, mainly because it serves to further legitimate the existence of the apparatus and tactically engages it where it is strongest. Conversely, popular resistance seeks to undermine institutions of power and target them where they are weakest: their political rigidity.

It is important not to view popular resistance as passive, moral or one-dimensional and embrace it as active, strategic, and dynamic. People power, or popular mobilisation, involves adopting a range of tactics that go far beyond street protests. Mass-based confrontational acts such as protests are far more effective as part of a diverse tactical repertoire, complemented by dispersed acts of resistance and opposition, like boycotts and strikes, and the development of parallel institutions. For this reason, popular resistance encourages broad and diverse participation, ensuring that movements stay more inclusive and democratic.

While popular nonviolent forms of resistance offer a strategically rigorous path ahead, we need to sound a cautionary note about co-optation. As the main arbiters of violence, states are extremely influential in defining which acts of resistance are deemed ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’. This dichotomy is reproduced through academia, the media, and non-government organisations (NGOs), which collectively can become a top-down force in a way that is exploitative and patronising. Movements and their prospective constituents must be steadfast in challenging this socialised and oppressive dualism, which seeks to define the parameters of resistance in such a way that neuters the potency of any genuine challenges to its hegemony.

Conclusion

Despite extensive training programmes and shiny new toys, the US counterinsurgency apparatus continues to indulge in its guilty pleasure: extravagant violence. The reasons for this are not complicated. Coercive US institutions were forged in a settler colonial project, chattel slavery, imperial excursions, neo-colonial domination and racial apartheid. Its underlying obsession with order is merely a twisted fantasy of upholding an archaic status quo that ultimately depends on merciless violence.

For those committed to challenging these structures and imagining a more just future, emancipatory movements –not electoral politics and reformist agendas – offer the most genuine way forward. While the asymmetry of power in these struggles is truly immense, closer inspection reveals vulnerabilities ripe to be exploited by an astute and coherent strategy. An interconnected movement based on informed solidarity, which stays true to the political nature of the struggle and employs strategies that undermine rather than reinforce the powerful, stands more than just a chance.

1 ‘Insurgency’ Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (1939, 5th ed.). Springfield, MA: G. and C. Merriam. See also ‘Insurgency’ Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/insurgency

2 Headquarters, Department of the Army (2014) Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies (FM3-24/MCWP 3-33.5)

3 Ahmad, E. (2006) ‘Counterinsurgency’, in C. Bengelsdorf, M. Cerullo and Y. Chandrani (eds.), The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad. New York: Columbia University Press, pp.36–64.

4 Ahmad, ‘Counterinsurgency’, in: C. Bengelsdorf, M. Cerullo and Y. Chandrani, (eds.), 59

5 Grenier, J. (2005) The First Way Of War: American War Making On The Frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 4–6.

6 Ibid., pp. 6–9.

7 Ibid., 53–86.

8 Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014) An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, p. 56.

9 Immerwahr, D. (2019) How to Hide an Empire: A History of The Greater United States. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, p. 110.

10 Arnold, J. (2009) Jungle of Snakes: A Century of Counterinsurgency Warfare From the Philippines to Iraq. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

11 Dunbar-Ortiz, (2014), p. 166

12 Ibid., pp. 164–165.

13 Ibid., p. 164.

14 Hadden, S. (2001) Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 207.

16 Potter, G. (n.d.) The History of Policing in the United States. [ebook] EKU School of Justice Studies. https://plsonline.eku.edu/sites/plsonline.eku.edu/files/the-history-of-…

17 Ibid., p. 5.

18 Ibid., pp. 4–5.

19 Ibid., p. 7. Schrader, S. (2019) Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, p. 74.

20 Ibid., pp. 54–62.

21 Ibid., pp. 53–54.

22 Ibid., p. 181.

24 Ibid., p. 155.

25 Wamsley, L. (2020) Shock and dismay after Trump pardons Blackwater Guards who killed 14 Iraqi civilians. [online]: https://www.npr.org/2020/12/23/949679837/shock-and-dismay-after-trump-p… [Accessed 23 December 2020].

26 Else, D.H. (2014) The ‘1033 Program,’ Department of Defense Support to Law Enforcement. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R43701.pdf

27 MacAskill, E. and Dance, G. (2013) NSA Files Decoded: Edward Snowden's Surveillance Revelations Explained. [online] https://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/nov/01/snowden-nsa-f…

28 The NYPD’s Discriminatory Surveillance of Muslim Communities. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/other/factsheet-nypd-muslim-surveillance-program

29 Researching the American-Israeli Alliance (2019), Deadly Exchange: The Dangerous Consequences of American Law Enforcement Trainings in Israel https://deadlyexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Deadly-Exchange-R…

30 Dougherty, S (2014), Palestinians have some advice for the people of Ferguson, Missouri, Global Post, 14 August 2014

https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-08-14/palestinians-have-some-advice-pe…

31 Ahmad, E. (2006) ‘Revolutionary warfare: how to tell when the revolutionaries have won’, in C. Bengelsdorf, M. Cerullo and Y. Chandrani (eds.), The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad. New York: Columbia University Press, pp.36–64; 17–18.