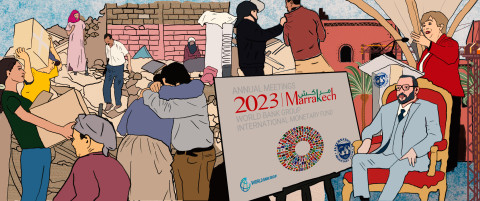

Disastrous capitalism in Morocco in wake of earthquake Between the hammer of International Financial Institutions and the anvil of Disaster Capitalism

On 8 September 2023, a devastating earthquake hit Morocco killing over 3,000 people and injuring thousands more. While grassroots solidarity initiatives mushroomed, the state’s relief response has been sorely lacking with deadly consequences. The impact of the earthquake was most severe in the most marginalised and poorest areas, especially in the countryside.

In this article, Ali Amouzai analyses the roots of this predicament, which lies, according to him, in the neoliberal hollowing out of the state, the privatisation of public services, the liberalisation of the insurance sector and the commodification of relief efforts, policies that have been dictated and encouraged for decades by International Financial Institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

As the Moroccan kingdom prepares to host the annual meeting of the IFIs in Marrakech between 9 and 15 October, the author argues that such neoliberal policies need to be challenged and that a recapture of the state from the claws of neoliberal markets and policy instruments has become essential for survival and emancipation.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The term ‘neoliberal earthquake’ may seem like a cliche, but in the context of the recent natural disaster in Morocco, it really does encompass some of the defining elements of contemporary capitalism. Indeed, it is hard to ignore the irony of an economic model that favors capital accumulation, and claims that wealth trickles down to all sectors of society, even as it fails to provide adequate aid or basic assistance to victims of natural disasters.

Just as the Moroccan state was preparing to highlight economic progress in Marrakesh and its surrounding regions at an annual meeting with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an earthquake pre-emptively laid the hollow nature of these assertions bare. On 8 September 2023, an earthquake measuring 7 on the Richter scale struck areas surrounding Marrakesh. The National Institute of Geophysics reported it as the most severe earthquake to hit Morocco in more than a century. As of 27 September, official figures state that 2,960 people have been killed and 6,125 people have been injured. The full extent of this disaster is yet to be grasped, but it is clear that its impact has been compounded by the state's criminal negligence.

Decades of economic policies have left millions of Moroccan workers vulnerable to natural disasters, including droughts, floods, wildfires, and earthquakes. The Moroccan state was hoping its October 2023 meeting with the World Bank and IMF would bring increased access to international financial markets and loans — the very foundations of this same development model that benefits the wealthy while impoverishing the poor and amplifying the effects of natural disasters. Amid the absence of adequate infrastructure, severe deterioration of public services and the fragility of roads in the affected areas, such economic decisions lend natural disasters class-based and spatial dimensions that disproportionately affect the poorer populations in rural areas and on the outskirts of major cities.

Potential Shortcomings in Seismic Activity Monitoring

The National Institute of Geophysics (ING) in Morocco operates around the clock, monitoring seismic activities and issuing warnings. It has been designated: ‘[T]he executing agent for Morocco in an agreement signed in December 2008 between Morocco and the United States of America (USA). This agreement aims to establish and operate a national seismic system.’1

As per the US Geological Survey (USGS), a US government agency that monitors natural resources and the natural hazards that threaten those resources, "earthquakes cannot be predicted accurately." At the same time, the USGS notes that "only scientists can calculate the probability of a major earthquake occurring in a given area within a certain number of years."2 And yet, the probability of earthquakes occurring in Morocco has never been definitively calculated. So far as the Moroccan state does tend to offer predictions, they tend to issue statements that downplay the likelihood of severe earthquakes. "The province of El Haouz, southwest of Marrakesh, has historically experienced weak seismic activity, both in terms of frequency and magnitude,” said Hani Lahcen, the Head of the Seismic Monitoring Service in Morocco. “Earthquakes recorded in the region have rarely exceeded 5 on the Richter scale. Therefore, historically, it is not known for earthquakes of this magnitude and strength.”3

On the same day the earthquake struck Morocco, 27 earthquakes occurred in various parts of the world.4 In many cases, people affected by those earthquakes had some forewarning about the risks they were facing. But there was no warning of the possibility of an earthquake in Morocco. Almost a year ago, on 12 December 2022, an earthquake with a magnitude of 3.3 on the Richter scale was recorded off the coast of Agadir. This was followed by a second earthquake a week later, also with a magnitude of 3.3. Despite these precedents, Moroccan authorities showed little concern that something like 8 September might be forthcoming.

These oversights do not stem from a lack of general knowledge about natural disasters. Reports from international financial institutions have already indicated that Morocco ranks among the countries most vulnerable to geological and climatic hazards in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Indeed, any reasonable assessment leads one to conclude that there is likely to be more, not fewer, natural disasters in the future. In fact, Morocco is bearing the brunt of climate change, which will almost certainly intensify the impact of related disasters. Projections suggest that by 2030, approximately 42% of Morocco's coastline will face a high risk of flooding and erosion. Coastal cities in Morocco, such as Rabat and Tangier, have been classified as 'extremely susceptible to floods’. With 77% of the population expected to live in urban areas by 2050, it is highly likely that the future population will be heavily concentrated in areas that are highly susceptible to flooding.5

In essence, the state has failed to make sufficient preparations to address this disaster, despite the comprehensive plans outlined in reports from international institutions and specialised bodies. Instead, the neoliberal economic model continues to shape disaster management. This leads the state to prioritise allocating public finances to investments yielding high capital returns over investments in social and environmental areas. This occurs despite the extensive publicity surrounding World Bank-funded efforts to monitor and mitigate natural disasters.

Disaster Capitalism

The absence of the state exacerbated the consequences of earthquakes and other previous disasters, including the 2022 Larache wildfires. The ‘new development model’ that has been prioritized by the state since 2021 discusses the ‘resurgence of a strong state’, but this seems to apply primarily to rescuing, stimulating and supporting the private sector, as was evident during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the midst of the pandemic, the state unveiled an economic revival plan (through sub-contracting to the private sector) with a financial allocation of $11.7 billion. In contrast, the Special Fund for the Management of the Covid-19 Pandemic has received $4.1 billion, of which $1.4 billion were disbursed to support 5.5 million families, and $584 million were allocated to compensate wage earners whose employment had ceased. These figures reveal the essence of the ‘strong state’ described in the new development model: where the state plays the role of a crutch supporting private capital and providing targeted, limited and temporary assistance to the workforce. This approach aims to limit social tensions and ensure social and political stability, while doing little to reform the underlying flaws of an unjust economic model.

Those living in the villages and marginalised neighbourhoods have all but been excluded from this new model of statecraft, except when the need arises for suppressing their struggles or placating them through charitable programmes aimed at alleviating poverty — often referred to as ‘social protection’. The impact of the earthquake was most severe in the most marginalised and poorest areas, including villages in the countryside, city peripheries and small urban centres such as Marrakesh, Chichaoua, Taroudant, Ouarzazate and Azilal. It further damaged the precarious living conditions of a population already impoverished by neoliberalism and state negligence. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the catastrophic earthquake of 8 September 2023 affected more than 300,000 people in the UNESCO World Heritage city of Marrakesh alone.6

The impacts of the earthquake were more severe in rural areas. After years of ostensibly promoting rural development, the state now cites the absence of infrastructure and roads as the reason it was unable to provide adequate aid to rural earthquake victims. This justification obscures a stark reality: the state is more than capable of intervening swiftly in some of these same places when it comes to suppressing resistance movements or in bailing out the private sector with public finances, but incapable of providing urgent disaster relief. This underscores the truths about the 'strong state' promised by the ‘new development model’. In fact, it is a state that acts efficiently to oppress the impoverished while supporting the affluent.

According to the latest report (in 2014) from the Higher Planning Commission, multidimensional poverty has historically been primarily a rural issue. In 2014, 85.4% of Moroccans living in poverty resided in rural areas, as compared to 80% in 2004. The report also highlights that Marrakech-Safi is the region with the highest poverty rate in Morocco.7 The state's neoliberal economic approach further perpetuates long running historical disparities within Morocco, reminiscent of the colonial-era divisions between the 'productive/useful' and 'unproductive/useless' regions (where the label ‘productive’ refers to the extent to which an area can generate profits). The contradiction goes further than this division itself and is also evident within major city centres. There, investments prioritise the development of robust infrastructure to attract private capital, while the outskirts remain home to millions of workers and marginalised communities. In cities, public finances are allocated towards modern infrastructure, including international airports, motorways, railways and the high-speed Buraq train. All of these are aimed at stimulating private investment, not necessarily serving the needs of local residents.

The longstanding practice of promoting private investment through infrastructure development funded from the balance sheet is not new, going back decades as documented by the publication of a report in 2006, entitled ‘The Possible Morocco: 50 years of human development’, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Morocco’s independence. The report highlighted that the finances of the Hassan II Fund for Economic and Social Development, derived from the privatisation of public enterprises, have been directed towards structural projects, encompassing both infrastructure development and those designed to attract private investments. The funds are allocated to programmes aimed at completing infrastructure and provide direct financial support to private investors.8 Similarly, the 2021 New Development Model, which remains government policy, reaffirms the crucial role of the public sector in enhancing competition within national economy and catalysing the private sector.

Neoliberal policies in Morocco are exacerbating the impact of natural disasters like earthquakes, floods, fires and droughts, creating a class-based dimension to these issues (where the precarious lives of the poor are disproportionately affected) and spatial dimensions (where the most marginalised areas in urban cities and the countryside are most impacted).9 This is not unique to underdeveloped countries, as austerity policies have led to similar consequences in much more developed countries such as the US. In the case of Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans in 2005, Noam Chomsky highlighted the role of budget cuts that were imposed on the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in the three years preceding the hurricane. These budget cuts exacerbated the disaster’s ramifications, revealing class and racial disparities, with a disproportionate impact on black, working-class, and poor communities. Chomsky concluded then that the neoliberalism of the Bush administration resulted in a state incapable of serving its citizens in general, highlighting yet another characteristic of a dysfunctional and failed state.10

In Morocco, reports from the World Bank and the IMF consistently emphasise the need to ‘review the role of the state’, a phrase that the Moroccan government frequently quotes verbatim. In practice, this translates into a reduction in the state’s social responsibilities. This leads to an increased focus on supporting private capital and an intensification of repression, exacerbated by the shifting social and political power dynamics of a post-decolonisation context. As applied to natural disasters, austerity in social infrastructure investments, including healthcare, education and disaster preparedness and prevention makes the impact of natural disasters worse.

Austerity has also impacted the Moroccan National Centre for Scientific and Technical Research (CNRST), which houses the National Institute of Geophysics. Budget cuts increasingly exempt the state from funding education and scientific research, as policies emphasise the need to 'diversify sources of funding’ by such institutes.11

Crisis Profiteers

In the aftermath of the 8 September earthquake, social media pages have been filled with expressions of outrage over crisis profiteering. This criticism is directed at major supermarkets, petrol stations that failed to reduce prices, and the railway company, which did not waive fares for solidarity convoys. These events are reminiscent of the substantial profits amassed by Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch's Oxygen company, which enriched itself through a monopoly on the supply of oxygen to healthcare institutions during the Covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, it is crucial to not overlook other significant crisis profiteers, including the World Bank, the state’s ruling elites and insurance companies.

The state’s ruling elites have approached disasters that are exacerbated by capitalism's destruction of nature, with the same capitalist perspective used to address the climate crisis. This approach views disasters as opportunities to accumulate profit through insurance and compensation mechanisms recommended by the World Bank, with a particular emphasis on so-called ‘post-recovery activities’. In this view, periods that come in the aftermath of shocks — whether natural, economic, or political — are seen as ripe for making profits.

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Mustapha Baitas, the government spokesperson, said that all official authorities in Morocco are currently directing their efforts towards completing the initial phase of relief efforts in preparation for a transition to the reconstruction phase.12 This translates into letting popular solidarity initiatives and charitable donations to the Earthquake Impact Management Fund take care of the non-profitable 'relief efforts' that need to conclude swiftly. Next, real estate and banking companies move in, to expedite the 'transition to the reconstruction phase’, which essentially aligns with the motto of 'sharing losses and privatising profits’, dear to public private partnerships.

Rather than focusing on proactive anticipation and prevention, a new insurance-centric approach has emerged in the last few years. The World Bank discusses this shift under headlines like ‘Supporting Morocco's Journey to Building Resilience to Disasters’. Instead of strengthening the resilience and anticipation system, the World Bank promotes loan-financed projects with the goal of ‘reducing disaster risk and strengthening the financial resilience of target populations to natural disasters… and support an innovative disaster risk insurance system that encompasses both the public and private sectors.’13 On 20 April 2016, the World Bank granted Morocco a loan of $200 million to fund the ‘Integrated Disaster Risk Management and Resilience in Morocco’ programme, which aims to ‘enhance the financial resilience of Moroccan households and businesses against natural and man-made disasters’.14

The Moroccan state embraced an insurance-centric perspective, lauded by the World Bank as an innovative risk insurance system in 2018 (Law No. 110-14). The policies came into effect in January 2020. The law introduced a specialised insurance mechanism covering approximately 9 million people and created a public fund, the Solidarity Fund Against Catastrophic Events (FSEC), separate from the Natural Disaster Fund, to support the poorest and the most vulnerable families — a population comprising roughly 6 million people. Collectively, the private and public insurance mechanisms offer approximately $100 million in compensation to those affected each year.15 This approach primarily benefits insurance companies, a fact confirmed by the World Bank itself when commenting on Morocco's Law No. 110-14: “It ensures coverage for families and companies through additional premiums received and managed by private insurance companies."16

Programmes like these receive funding from both bilateral and multilateral sources. For instance, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) has allocated $300 million through the Integrated Natural Disaster Risk Management and Resilience project, utilising the Programme-for-Results Financing (PforR) instrument.17 In addition, various technical assistance initiatives, funded by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery and the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, have contributed approximately $1.5 million to support the Natural Disaster Impact Fund, the National Strategy for Disaster Risk Management and other initiatives to enhance urban resilience and activities related to financing and insurance for disaster risk activities in the regions.18

On 12 September 2019, the government issued two decrees to address the impact of catastrophic events. One decree mandated that the damage caused by these events be covered in insurance contracts, while the other established a solidarity fee to mitigate the consequences of catastrophic events.19 In alignment with its broader perspective of ‘universal social protection’ and akin to previous initiatives like the 'healthcare coverage’, the state has earmarked some resources for the less privileged, who are not typically attractive to private sector insurers. This support is facilitated through establishing a 'solidarity fund against catastrophic events’, funded by a financial allocation from the state budget and proceeds from quasi-tax fees known as the ‘solidarity tax against catastrophic events’. This solidarity tax seeks to divert 1% of premiums, additional fees, or contributions within insurance contracts related to non-insurance processes into a fund to boost the collective purchasing power of individuals that would otherwise have little.20

The concept of ‘financial balances’, favoured by international financial institutions, acknowledges the importance of ‘catastrophe insurance’. According to Law 110.14, the natural Fund is required to adopt an effective and appropriate strategy to develop innovative solutions that strike a balance between providing comprehensive coverage of those affected and considering the financial constraints faced by the Fund. As a result, the funds allocated for covering catastrophe risks may be reduced. These ‘innovative solutions’ often resemble the questionable practices employed by insurance companies to mitigate the financial burden of covering damage resulting from accidents. Such practices may involve seeking assessments from experts with affiliations to the insurance companies, enforcing stringent notice deadlines, delaying compensation, or creating disparities between the compensation offered and the actual extent of the damage incurred.21 The situation is exacerbated by the fact that the insurance sector has been completely liberalised in Morocco since July 2006. As a result, insurance premiums are no longer subject to regulation, and they have been excluded from the list of goods, products and services subject to price control.22

Maroc Marrakech Jemaa-el-Fna/Luc Viatour/CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

A Sluggish State and Excessive Bureaucracy

Reports from international financial institutions consistently criticise the centralised state and the bloated public sector, which they characterise as slow and overly bureaucratic.23 In practice, the state exhibits a stark contrast in its responsiveness — quick to intervene when it involves injecting funds into businesses and banks from public finances, yet sluggish, or even absent, in addressing the social and economic rights of millions of workers or implementing relief measures for natural disasters.

Capital does not favour a state that intervenes by imposing taxes and financing public and social services. Instead, it seeks a ‘low-cost state’ in response to the demands of workers, all under the guise of funding projects to stimulate enterprises and securing profits. The concept of a ‘low-cost state’ was originally associated with the labour movement but has since been co-opted by neoliberalism to serve corporations and capital. As a result, international financial institutions criticise public sector inflation and excessive bureaucracy, suggesting its dismantling and transformation in favour of a more efficient and less bureaucratic private sector.

Whenever a natural disaster strikes, the public often asks: ‘Where is the state?’ The answer can be found in the excessively bureaucratic nature of the insurance systems to which the state delegated the matter of covering for catastrophe risks and compensating for them.24 The complexities of these procedures are designed to maximise insurance premiums while minimising compensation pay-outs. Contrary to claims of private sector efficiency, when it comes to for-profit companies, excessive bureaucracy is often deemed acceptable! It is a system that manages to combine poor responsiveness with the profit motive.

The updated law for addressing the consequences of catastrophic events introduces new governance mechanisms, including a committee responsible for monitoring such events. The committee is mandated to oversee the implementation of disaster relief and to collaborate with state administrations, government departments, territorial collectivities (regional authorities) or any relevant bodies to gather comprehensive information. Moreover, its role includes providing recommendations to the government regarding the potential catastrophic nature of an event and assisting the solidarity fund (FSEC) in evaluating the damage suffered by victims.25 Unfortunately, this intricate bureaucratic web leads to minimal concrete intervention.

While citizens were either starving or trapped beneath rubble, and grassroots solidarity initiatives were springing up spontaneously and swiftly, the government spokesman wasted time reviewing administrative and bureaucratic procedures.26 Eventually, a decree was issued to establish the Earthquake Effects Management Fund, with the capacity to receive donations. This sort of negligence has proven more deadly than the earthquake itself.

The State Hijacks Local Solidarity Efforts

In response to the burgeoning grassroots solidarity initiatives, the state established a dedicated fund known as 'Special Fund 126 for Management of Earthquake Impact’. This move represents a stark reversal of the state’s approach in championing its withdrawal in favour of other entities, civil society and the private sector. Instead, it seeks now to co-opt and manipulate the collective solidarity efforts of the populace, mirroring its actions during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The fund will be financed by donations aimed at rebuilding and reconstructing damaged homes, providing support to those in dire circumstances and allocating funds to encourage economic operators to swiftly resume activities in the affected regions.27 This arrangement means that citizens finance the reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts, while the state poses as the benefactor as it oversees the process through a fund established by decree. Meanwhile, the private sector stands to profit from the reconstruction efforts.

In a state marked by authoritarianism, these funds serve a political purpose by exerting control over grassroots initiatives. The ruling classes view citizens organising to collect and provide aid as 'unauthorised fundraising’, which they deem problematic. Instead, they prefer to rely on bureaucratic mechanisms like decrees, funds and ministerial committees, as well as monetary collections conducted through direct bank transfers or indirect online payments. This approach enables the state to sidestep collective debates, dismantle solidarity movements and fragment them into individual entities.

Capitalists favour these voluntary funds, which allow them to share the costs of the crises they cause with those who are affected. They oppose levies on profits and assets and prefer funds where they have some kind of control, rather than the state or the law, to determine the proportion of their contributions. After the disaster abates, the profits they accumulate greatly surpass any contributions they made.

The Neoliberal National Consensus

In addition to the economic and material benefits derived from such crises, the Moroccan state seizes every opportunity to promote the myth that there is some sort of national consensus over its policies. Social media platforms are flooded with references to the ‘patriotic spirit' that united Moroccans in aiding and rescuing the victims of earthquake-stricken areas.

However, beneath this wave of patriotism, the only consensus that exists is between the state and international financial institutions, as they both aim to establish their methods as ‘national norms’. This consensus revolves around the idea that the state should not bear sole responsibility for natural disasters, including their associated risks and consequences. This perspective closely aligns with Article 40 of the Constitution, which stipulates that: ‘Everyone must support with solidarity and proportionally to their means, the expenses that the development of the country requires, and those resulting from calamities and from natural catastrophes.’ This is but another side of the same coin that holds ordinary families, civil society and the private sector responsible for providing public services, such as healthcare, education and housing. Consequently, the role of the state is limited to mobilising available resources to ensure that citizens can access these services.

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, a familiar pattern emerged where many voices called for the suppression of critical perspectives aimed at holding the state accountable for its policies. They argued that this was a time for solidarity, assistance and rescue, not a time for questioning and criticism. This makes it seem as if Morocco is a haven for freedom of expression during non-disaster times, which it is not. The state capitalises on this situation. In moments of crisis and disaster, the masses often come together and begin to uncover the harsh realities of their society. As they grasp the depth of their historical backwardness, they may seek redress through significant actions, which could manifest as a revolution or an uprising. To abstain from criticism and from holding the state and capitalism accountable at such a juncture is to miss a rare opportunity. The state, in turn, seizes this opportunity to cement its grip and perpetuate its neoliberal economic policies.

Today’s surge of national pride will likely be short-lived, as it has been in the past. People will soon confront the cruelty of a grinding state that swiftly intervenes to suppress them or to rescue capitalist corporations, but that cannot efficiently assist victims of natural disasters. Similar to what occurred in Al Hoceima in 2004 following a devastating earthquake, ordinary people will rise up to rebuild their homes and to reconnect villages to essential services/infrastructure like roads, electricity and water. At that moment, the oppressive nature of the state will once again become apparent. It is crucial to maintain a critical mindset and a discerning approach toward the authoritarian neoliberal state, resisting the allure of superficial patriotic sentiments.

Streamlining and Mobilising Popular Solidarity Efforts

Grassroots solidarity campaigns, organised via social media, sprang into action to fill in for the stagnant state apparatus. As a result, numerous convoys from various cities managed to reach the most challenging earthquake-affected areas even as the state cited difficult terrain as an excuse for its failure to help those in need.

These are commendable and crucial acts of solidarity. They affirm the continued existence of a sense of collective belonging, countering decades of neoliberal propaganda that prioritises the ‘individual’ over the ‘collective', ‘individual freedom’ over 'collective liberation’, and individual initiative and competition over cooperation and solidarity.

The absence of strong organised structures and the inability of trade unions to centre class struggle in popular solidarity campaigns often lead to these efforts being absorbed by the bureaucratic institutions of the neoliberal state. Additionally, the absence of a centralised organisation for aid distribution can result in inflation, uneven allocation of resources and potential waste, especially when it comes to food. This disorganisation may also attract opportunists who misuse funds. Then the state seizes on these issues to portray people as incapable of self-management and justifies its bureaucratization and commodification of solidarity.

Taken as a whole, this can lead to the quick dissolution of popular solidarity, which fades amid a lack of resilience. Many participants in solidarity campaigns will return to their jobs, leaving the poor alone and isolated. We should also acknowledge that these necessary solidarity efforts only address the symptoms, offering temporary assistance to victims but not tackling the root cause: disaster capitalism. The state capitalised on the disorganisation and lack of centralisation in these solidarity campaigns, effectively channelling them into its bureaucratic institutions. It directed the solidarity efforts towards the ‘earthquake management fund’, benefiting politically from a surge in popular solidarity that filled the void left by its absence.

Towards an Alternative Society

Capitalism has entered an era of severe crises, encompassing various dimensions that collectively challenge the foundations of bourgeois civilisation. These crises have become commonplace, spanning climate-related issues, pandemics, environmental disasters, economic downturns, conflicts and the emergence of far-right and reactionary religious movements. The weight of this crisis is disproportionately borne by the populations of the global South and the working classes in the imperialist cores.

The root of these crises lies in the widespread commodification of nature and every facet of human activity. This commodification fuels economic and political crises, fosters conditions conducive to environmental and epidemiological disasters and heightens the risks associated with natural calamities. Attempts to make capitalism ‘green’ or more ‘humane’ will only prolong a system that is destroying the environment and humanity.

A struggle is imperative to defend our shared resources, counter the commodification of nature and human activities and reinstate the principles of collective cooperation and public services. This should be under the direct control of direct producers, including wage earners and small producers, as well as consumers.

International financial institutions use state indebtedness to enforce their neoliberal agendas. These agendas promote privatisation of public enterprises, the commodification of public and social services, and prioritise profit accumulation, often neglecting essential expenditures for disaster prevention, preparedness and protection, as they are not deemed profitable. At a system level, these preferences are embedded in institutions, states and companies alike.

It is crucial to be prepared for future waves of resistance. In due time, those affected by the earthquake will likely feel compelled to protest. We should seize the opportunity to come together, leverage existing solidarity campaigns, establish networks to support these struggles, and engage in discussions about the root of the problem: neoliberal state policies that worsen the impact of natural disasters.

We should not confine our efforts solely to the immediate task of providing material support, which includes collecting essentials like food and clothing. Instead, we should view these acts of solidarity as a chance to construct grassroots networks. These networks can be platforms for discussing the problems faced by rural areas and marginalised urban neighbourhoods like poverty, unemployment, lack of infrastructure and low literacy rates.

Last but not least, we must fight for the abolition of illegitimate debts and strive for the collective control of our shared resources, including land, public and social services, free from the limitations imposed by market-driven commodification. Ultimately, the struggle for survival, emancipation and popular sovereignty entails the recapture of the state from the rule of greedy and repressive elites and from the claws of neoliberalism and disaster capitalism.

This article is an edited translation (from Arabic) of an article published by our partner ATTAC-CADTM network. To read the Arabic version, click here.