Techwashing and fascist politics A case study of Israel’s ‘Start-Up Nation’

Temas

Regiones

Israel has sold itself as a laboratory for positive tech innovation that obscure its development of digital technologies that underpin state systems of violence and mass surveillance. This techwashing legitimises occupation and oppression at home and inspires authoritarian tech-dystopias worldwide.

Illustration by Sana Nasir

The origin of Israeli techno-fascism

Early Zionism drew deeply on nineteenth-century European ideologies: white supremacy, racial hierarchies, colonialism, nation states, fascism, and messianic evangelism. Like Italian futurism under Mussolini, Zionism admired progress, science, and technological transformation. The movement and its early state apparatus were led largely by scientists and technocrats, often inspired by German colonial models. Innovation and technology became central political forces shaping collective life. Jewish people were invited to reinvent themselves as a new kind of subject, embodied in Max Nordau’s concept of ‘Muscular Judaism’ and the Zionist ideal of Nietzche’s ‘Übermensch’ [superhuman]. The early settlers were thus the ideological ancestors of today’s Israeli entrepreneurs.

Theodor Herzl’s The Jewish State best articulates this technocratic and civilisational agenda. He repeatedly underscores the role of science and modernity, insisting that ‘the establishment of a Jewish state presupposes the application of scientific methods’. The pamphlet’s concluding promise – that ‘the world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness… and whatever we attempt there will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity’ – encapsulates the techno-civilisational mission at the heart of the early Zionist project.

The colonisation of Palestine was, as Herzl had planned, framed as a civilising project in which European science and technology justified the settlement of Israel and the massive displacement of Palestinians. ‘The Jews have made us prosperous, why should we be angry with them?’, asked Rashi Bey, the only Arab character in Herzl’s novel Altneuland. Agricultural, medical, and technological achievements, such as ‘making the desert bloom’, were portrayed as evidence of moral righteousness, beneficial to both Jews and the indigenous Palestinian population, masking the violence of colonisation and presenting dispossession as progress.

This logic mirrors European colonial practices, where claims of economic and environmental improvement justified land appropriation and the subjugation of local populations. The ideological and material roots of Israel’s Start-Up Nation narrative thus lie squarely in this technocratic colonial lineage.

An innovation or ‘killing lab’?

The technocratic governance structures of the 1920s laid the foundations for today’s seamless fusion of high-tech, militarism, and politics, a ‘military-technological complex’ that defines Israel’s political economy. After the 1967 war and the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, and East Jerusalem, military technocrats moved into civilian administration. Working closely with politicians, they developed policies that nurtured the high-tech sector: subsidies, deregulation, incentives for foreign investors, and flexible export controls. Support from the United States (US), which always saw Israel as its imperialist bastion in the Middle East, was decisive. Beginning with the 1977 BIRD Foundation, Washington poured millions into Israel’s nascent tech sector and opened doors to US markets. In the 1990s, the Yozma programme ignited Israel’s venture-capital (VC) industry through massive state co-investment. These foundations were strengthened by sweeping neoliberal reforms from the 1980s and deepened under Netanyahu: privatised state assets, tax cuts, liberalised markets, and accelerated flows of foreign capital.

Israel thus became a global techno-fascist hub, with over 430 multinationals with offices in the country, alongside 350 VC firms. Israel hosts around 9,000 start-ups, with 130 companies listed on NASDAQ. High-tech now generates roughly 20% of gross domestic product (GDP), 56% of exports, and 25% of tax revenue.

What was the cost of building a Start-up Nation? Even Zionist commentators are now criticising a failed state: ‘A Jewish state in which its citizens live in poverty, inequality, or lives of quiet economic desperation is, at best, a very bitter joke’. Israel is among the most unequal members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with 20% living under the poverty line. Tel Aviv is one of the world's most expensive cities, and the country faces a deep housing crisis (another reason for its settler-colonial project in the West Bank). Not to mention the (economic) apartheid that Palestinian Israelis experience (‘48 Palestinians’), demonstrated by their lack of infrastructure, including anti-missile shelters.

While most politicians came from the armed forces, a new generation moves between politics and high-tech: the former prime minister Naftali Bennett sold two tech companies for over US$250 million before entering politics; Ehud Barak is the founder of a spyware start-up, President Isaac Herzog is an angel investor and former officer in Unit 8200, Israel’s elite cyber warfare unit. Chemi Peres, the son of Shimon Peres, is a leading venture capitalist.

In 2024, as Israel escalated its assault on Gaza, its military budget rose by 65% to US$46.5 billion, 8.8% of GDP and projected to grow by another 20% in 2025. Military exports also hit a record US$14.8 billion. Maintaining a settler-colonial regime of ongoing occupation and dispossession provides a laboratory for weapons, tested on Palestinians and then exported as ‘battle-proven’ technologies to democracies and dictatorships alike. Israel has long supplied arms to conflicts, coups in Latin America, and genocidal forces, including Rwanda, where Hutu militias had Uzis, and apartheid South Africa, whose Bantustan model was praised by Ariel Sharon as a template for pacifying Palestinians.

The broader high-tech ecosystem – AI, cybersecurity, agritech, digital health – anchors Israel’s global influence. Even as Big Tech AI-powered systems facilitate genocide19 in Gaza, deals such as Google’s US$32 billion purchase of the cybersecurity firm Wiz or Palo Alto Networks’ US$25 billion acquisition of CyberArk show the deep ties between global markets and this economy of violence. Thousands of global companies benefit from this economy of genocide, as highlighted in the recent report by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in the Occupied Territories.

This ‘battleship of Israel’s economy’ needs to be dismantled. It is not enough to boycott arms companies or firms profiting directly from illegal settlements: the entire start-up ecosystem underpins Israel’s ethno-fascist high-tech state. Political economists such as Shir Hever note that Israel’s extreme dependence on a militarised high-tech sector that employs barely 10% of the workforce creates a bubble that may threaten the state’s long-term survival. With the rising costs of permanent occupation, militarisation and a deepening neoliberal fascist populism, especially after 7 October, the ‘Start-Up Nation’ façade is cracking.

The deadly Hamas attack of 7 October hit at the heart of the high-tech elite, including the son of a former government minister and the daughter of an Israeli tech billionaire, once celebrated in Israel for promoting ‘peace’ by employing Palestinians. The assault exposed the limits of Israel’s technological hubris: the Start-Up Nation was undone by low-tech means, while Unit 8200 had months of warnings but failed to act. Israel’s response, by contrast, was one of technological overkill: AI-driven targeting systems like Lavender, automated warfare like Gospel.

While some predict that Israel will become a failed state, we should not to wait for Israel’s potential collapse. Civil society needs to deconstruct the myth of Israel as a progressive, unassailable tech ‘bastion’. This begins by ensuring that business leaders, tech workers, business school students, and techno-optimists understand that Israel is not a model of innovation serving humanity, but a state whose high-tech sector underpins ongoing occupation and ethnonationalism. Only by challenging the perception of ‘the Start-Up Nation’ will it be possible to exert coordinated pressure on politicians, sanctions, and achieve systemic change.

Deconstructing Israel’s ‘Start-up Nation’: a marketing construct

The idea of a modern, progressive Israel is the result of a deliberate state-sponsored rebranding campaign. The Start-Up Nation discourse casts Israel as an open, creative, secular, Western society, strategically obscuring the political realities of occupation.

The second Intifada (2000–2005) tarnished Israel’s global image, especially among younger generations, who increasingly associated the country with colonisation, violence, and religious nationalism rather than with democracy or progress. In this context, Ido Aharoni, who joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2002, began promoting ‘nation branding’ as a new form of public diplomacy. He founded the Brand Israel Group, laying the groundwork for a strategy to shift international attention away from the conflict and towards a carefully curated set of ‘positive’ narratives.

Backed by vast government funding, and supported by figures such as Shimon Peres, Ariel Sharon, and Avigdor Lieberman, Aharoni’s team partnered with global PR and marketing firms. Their premise was simple: since most international audiences are indifferent to the conflict, the most effective tactic is not persuasion but distraction. The new story about Israel centred on dynamism, innovation, cuisine, wine, culture, renewable energy, water technologies, sports, and the LGBT-friendly Tel Aviv.

This strategy produced various image-laundering practices: pinkwashing, promoting Israel as a gay-friendly haven; greenwashing by highlighting environmental technologies and how Israel ‘made the desert bloom’; veganwashing (‘the most vegan army in the world‘), and of course techwashing, positioning the country as the ‘Start-up Nation’. The ‘creative energy’ campaign, launched in 2010, encapsulated this logic, branding Israel as ‘a dynamic and energetic place; a place whose substance is building a better future; and entrepreneurial enthusiasm’:

‘The goal is not to replace the conflict, but to become a multidimensional brand. I want to be in the situation where someone says: “I don't agree with your policies towards the Palestinians, but you invented this medical camera that saved my mom's life–and I appreciate that”.’Ido Aharoni citing Amir Reshef Gissin (former director of the Hasbara department)

For Hasbara, the government’s propaganda apparatus, this novel aim was to present Israel to the US and Europe as cosmopolitan, progressive, Westernised, and democratic, in contrast with the supposedly ‘backward, repressive, homophobic’ Islamic nations surrounding it. This, in turn, reinforced the idea that Israel’s aggression was not imperialism but the defence of democracy and freedom. Israel was to be known less for checkpoints and more for mobile apps, medical devices, wine exports, and gay pride parades. The strategic implications were clear: if Israeli technology became indispensable to global capitalism, boycotts would be nearly impossible, echoing Hasbara ambassadors Youssef Haddad and Emily Shrader’s anti-Boycott propaganda video. Becoming a ‘Start-Up Nation’ was therefore not just about prestige; it was a structural defence against the Boycott, Divest and Sanctions (BDS) movement (launched in 2005), ensuring that media, political elites, and above all economic leaders, would perceive Israel as a vital partner. This logic was presented at the 2010 Herzliya Conference, organised by the Reut Institute, ‘Winning the Battle of the Narrative.’ Bringing together the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Anti-Defamation League, NGO Monitor, and the Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre (BICOM), the conference sought ‘imaginative, effective and fruitful solutions’ to the ‘scourge’ of BDS. The task, as they framed it, was not only to ‘defend’ Israel’s reputation but to go on the offensive – crafting narratives in which criticism of Israel was marginalised by stories of innovation and progress.

The Start-Up Nation

‘Our book Start-Up Nation showed that every conversation about Israel doesn’t have to be about the settlements.’ Dan Senor, co-author

The Start-Up Nation was popularised by Dan Senor and Saul Singer’s 2009 bestseller, Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel's Economic Miracle. In many ways, it did more for the country’s branding than any official government campaign. Today, a Google search for ‘Start-up Nation’ immediately leads to Israel. With over a million copies sold and rights licensed in more than 30 countries, the book became a powerful promotional tool – precisely because it appeared to be independent, offering what looked like an ‘objective’ account of Israel’s economic miracle.

But the book is far from neutral. It was published under the aegis of the Washington-based Council on Foreign Relations, a powerful conservative and pro-Israel think-tank. Senor, a former George W Bush adviser and senior official in post-invasion Iraq, and Singer, a Jerusalem Post journalist and former US congressional adviser, interviewed CEOs of major US corporations, top Israeli leaders, and entrepreneurs. The foreword is by Shimon Peres, and the book includes conversations with Benjamin Netanyahu, and acknowledgements thanking ‘Bibi’, reflecting their recognition of the book’s potential to shape global perceptions of Israel.

Start-up Nation celebrates militarisation and a war economy dressed up in the language of neoliberal economics. Military service is presented as the jumpstart for aspiring techies, soldiers becoming ‘battlefield entrepreneurs’ (title of Chapter 2). Nowhere does it mention the annual US$3.8 billion from the US that underpins Israel’s economy, nor the US$310 billion (adjusted for inflation) in total economic and military assistance since 1948. Nor any reference to the occupation, not one word in the entire book. The authors even present the Six-Day War as a decisive bonanza for infrastructure and technological development. In short, Start-up Nation is a pro-Israel manifesto dressed up as business analysis. It offers a carefully curated myth that flatters Israel’s leaders and their allies abroad. As Senor said, ‘One could make the argument that the ultimate antidote to delegitimisation, isolation, and divestment is legitimisation, integration, and investment’.

From bestseller to bureaucracy: Innovation as Statecraft

The ‘Start-Up Nation’ narrative was rapidly institutionalised. Just a few years after the book’s publication, Startup Nation Central (SNC) was founded in Tel Aviv – a supposedly apolitical ‘free acting NGO’ that promotes Israel’s tech ecosystem worldwide. In reality, SNC is 95% financed by the US billionaire Paul Singer, a central figure in neoconservative circles, major Republican donor, close Netanyahu ally, and the former employer of co-author Dan Senor, in its hedge fund Eliott Investments. Singer, Senor, and Ron Dermer – who recently resigned as Israel’s Minister of Strategic Affairs – form a closed circle of pro-Netanyahu, ultra-conservative Republicans, tied to Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign and openly opposed to Palestinian statehood.

‘The argument is: Israel’s startups contribute to humanity on a daily basis, from water to agriculture to medicine. If you boycott Israel, you are basically boycotting humanity.’ Paul Singer, CEO of Eliott Management.

The authors of Start-Up Nation helped shape the narrative and then built the institution that perpetuates it: they co-founded SNC and remained on its board for years. Wendy Senor-Singer is Dan Senor’s sister and the wife of Saul Singer. After a 17-year career at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the main US pro-Israel lobby, she served as SNC’s first director (2013–2022), working alongside Eugene Kandel, Netanyahu’s former economic advisor. These overlapping relations reveal a political family network rather than an independent civil society organisation (CSO).

This ‘NGO’ has over 100 staff, including former diplomats and Unit 8200 intelligence officers. In reality, SNC was created not only to counter BDS but also to advance Netanyahu’s strategy of integrating Israel’s military-tech complex into global markets, most notably by placing former military and intelligence officers in key roles across major tech companies, for boycotts to become structurally impossible. This tactic has been documented by investigations from MintPress and, more recently, Drop Site, which traced Big Tech’s systematic recruitment of Unit 8200 alumni.

‘[Exporting technology] is very much my plan. What I ended up doing was to trim the public sector, help the private sector and remove the barriers to competition. I fight regulation with machetes[...] because having reformed the Israeli economy, we got the prowess of technological advance [...] This is a triangle. It's economic power and security power that gives you diplomatic power.’ Benjamin Netanyahu (interviewed by Fox News in 2018)

Today, SNC sits at the heart of Israel’s techwashing strategy: Israel exports a polished ‘innovation playbook’ to draw in investors, corporations, and governments. As with any start-up pitch, the image precedes the substance, and the narrative becomes a self-fulfilling source of legitimacy. SNC is more than propaganda, it hosts policymakers, tours for corporate delegations, sends entrepreneurs abroad, and seals business deals that blend innovation with diplomacy, turning Israel’s high-tech ‘miracle’ into a geopolitical shield. Even during the genocide, Israeli start-ups operated in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) under SNC’s umbrella.

‘I want France to be a Start-up Nation, a nation that works with start-ups, but also thinks and acts like them.’ Emmanuel Macron, in a 2017 speech at Vivatech

Under the banner of ‘Innovation Diplomacy,’ Israel has turned its high-tech ecosystem into a tool of foreign policy: a way to counter BDS pressure, strengthen alliances, and expand geopolitical reach across liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes alike. The ‘Start-Up Nation’ narrative has inspired governments worldwide, from French Tech in Macron’s 2015 visit to Israel, to the Baltic states, and Romania’s cybersecurity partnerships. In Africa, the fusion of high tech, aid and militarism is even clearer: Israel has signed cooperation deals with Kenya and Rwanda, while companies like Netafim (agriculture) and Mekorot (water) operate as extensions of state policy. Projects framed as humanitarian innovation, such as the Green Horizon initiative in South Sudan, served as fronts for arms deals worth $150 million to both sides of the civil war, despite international embargoes. Meanwhile, Israel’s ‘spyware diplomacy‘ paved the way for normalisation with African countries and Arab states through the Abraham Accords: NSO Group’s Pegasus was sold to governments from Morocco to Ghana, Egypt the UAE and Saudi Arabia, facilitating the global repression of journalists and human rights defenders.

Start-Up Nation and the SNC institution are two pillars of the same techwashing strategy, mutually reinforcing myth and machinery, constructing Israel’s image as a fortress of innovation. Using the language of ‘progress’ it provides a replicable playbook to legitimise ultra-neoliberal policies, militarism, and settler-colonialism.

‘In a world seeking the key to innovation, Israel is a natural place to look. The West needs innovation; Israel’s got it’ Start-Up Nation (Introduction, p.20)

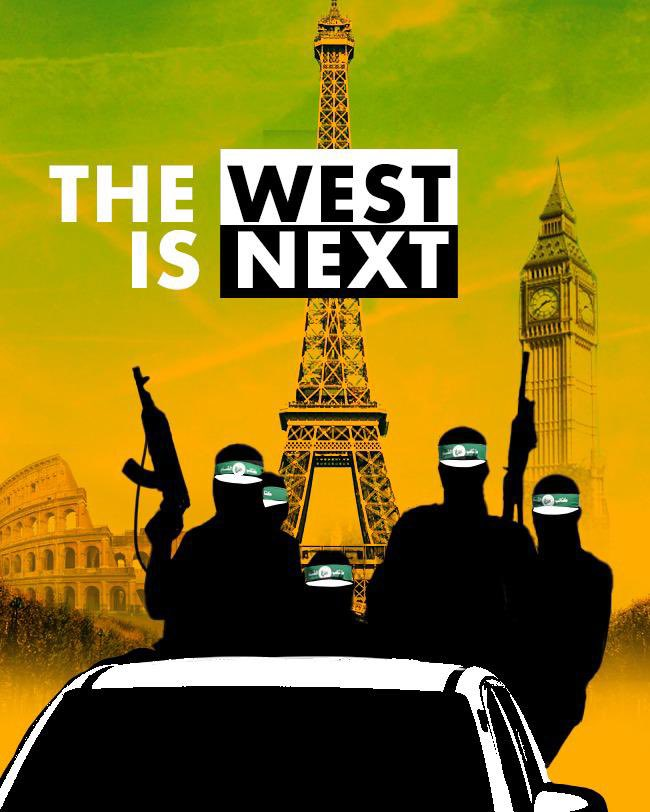

This narrative of technological bastion is inseparable from a broader ideology of exceptionalism and orientalism. Start-Up Nation fosters this portrayal of Israeli traits like chutzpah or bitzuism (‘getting the job done’) as drivers of success, while depicting neighbouring Arabs as backward or hostile. In this framework, Israel becomes not just a nation, but a start-up itself: the West’s last bastion of civilisation and progress against a supposedly regressive East, dangerously echoing the controversial ethnocentric controversial thesis of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, praised and cited in the Israeli innovation bible. Several investigations have shown how right-wing conservatives, such as Sheldon Adelson (one of Trump’s first supporters), Paul Singer (SNC’s patron), Irving Moskowitz, and Bernard Marcus, among many others, are funding Western Islamophobic think-tanks as well as Zionist pro-settlement organisations, proving the civilisational agenda. Israel has also had a strong influence in spreading Great Replacement theory, notably through Bat Ye’or’s Islamophobic conspiracies, Eurabia, that following the 1973 crisis, Arabs blackmailed the West to provide oil in exchange for mass immigration and Europe’s Islamisation. This reminds us of Israeli propaganda following 7 October: ‘The West is Next’, a hashtag and slogan that has been widely shared from official Zionist accounts.

|

|

| “Rome and Jerusalem are both the targets of radical Islam: Israel is on the frontline, but the West is next.” — Emmanuel Navon, CEO of ELNET Israel Source: https://www.instagram.com/westisnext/reels/ | https://x.com/LTurkishdizi/status/1721566468049928353?s=20 |

|

ELNET: the embodiment of techwashing and civilisational narrative

It is important also to explore the European Leadership Network, ELNET, the continent’s equivalent of the AIPAC in the US. This ‘non-partisan organisation working to strengthen relations between Europe and Israel by promoting political, strategic, and diplomatic cooperation based on shared democratic values and mutual strategic interests’ builds technological bridges between the European Union (EU) and Israel, while cultivating political alliances against Islam(ism) in the name of secularism and progress. At an ELNET-organised 4,000-person event in Paris in March 2025, France’s Minister of the Interior, Bruno Retailleau, publicly declared ‘Down with the veil’, equating Muslim women’s clothing with extremism.

Technological advancement further reinforces Israel’s civilisational agenda, portraying the country as a beacon of modernity and the Western fortress in an allegedly ‘backward’ Islamic region. ELNET works closely with SNC. In 2020, they established the German-Israeli Network of Startups & Mittelstand (GINSUM), connecting Israeli start-ups with medium-sized German companies, with state co-funding. While SNC sends business delegations abroad to secure deals, ELNET brings European policymakers and politicians to Israel to craft a positive narrative, showcasing innovation as a tool of soft power. Delegation agendas combine emotional visits to sites such as Yad Vashem or the Nova Festival with tours of Israeli start-ups and research centres, highlighting Horizon Europe-funded projects. This dual strategy legitimises Israel internationally while deepening EU–Israel ties.

In sum, SNC and ELNET form a complementary system. SNC promotes Israel’s innovativeness, progress, and business opportunities to the world, projecting a narrative technological salvation; while ELNET advocates for closer European cooperation, fostering diplomatic and political support and reinforcing Israel’s civilisational myth and framing it as an indispensable partner. Together, they institutionalise a narrative that blends tech diplomacy and political influence, ensuring Israel’s global positioning as both a start-up hub and a strategic actor in international relations.

High-Tech Zionism and GAZA crypto-currency

Entrepreneurship and high-tech are central to Israel’s state-building and national identity, with innovation framed as a political project. It governs citizens or subjects, sustains nationalist infrastructure, and projects power abroad. Technology reinforces Zionism itself, deepening belonging to Israel’s supranational project. I term this fusion of technology and statecraft High-Tech Zionism. The state actively cultivates citizens as high-tech entrepreneurs who advance national development and serve as ambassadors of the Start-up Nation, while mobilising and steering civic participation through a state-orchestrated social-media strategy to defend Israel online.

High-Tech Zionism also facilitates the privatisation of state functions under the veneer of ‘apolitical’ engagement. ‘Peacebuilding’ is outsourced to people-to-people initiatives like Tech2Peace, or embodied by the Shimon Peres Center for Peace & Innovation to ‘bring people together’; surveillance and cyber-espionage are delegated to private firms such as NSO Group or Toka (founded by former prime minister Ehud Barak); international development projects are channelled through non-profits like Nura Global Innovation Lab or Innovation:Africa – whose presentation video is brazenly neo-colonial; and diplomacy flows through institutional actors like SNC or lobby groups like ELNET.

High-Tech Zionism is inherently transnational. The ‘Israeli high-tech identity’ is exportable: start-ups and their global networks carry the state’s values abroad, legitimising Israel’s actions and raison d’être under the banner of progress, innovation, and entrepreneurial capitalism. Unsurprisingly, this narrative resonates strongly in Silicon Valley.

Balaji Srinivasan, the former partner at mega-fund Andreessen-Horowitz (whose founders just endorsed Donald Trump) and ex-CTO of Coinbase, advocates the end of nation-states and democracy in favour of ‘Network States’ of sovereign tech territories. ‘What I'm really calling for is something like Tech Zionism’: seizing territory to build a patchwork of start-up societies, bound not by democracy but by capital. Projects like Prospera in Honduras, Praxis Nation, or AfroPolitan, are popping up. The techno-fascist Curtis Yarvin theorised this model as early as 2008 in his Patchwork essays, now explicitly calling for democracy to be replaced by a corporate-tech dictatorship. In his blog, Gray Mirror, he even proposed a cryptocurrency called GAZA as a ‘solution to the conflict’ – suggesting what ‘network-state’ governance might look like there, post-genocide.

‘Trump may not grasp the theory behind the Network State. But he embodies it: authoritarianism disguised as innovation. Sovereignty sold to the highest bidder. Capitalism without constraint. Fascism — maybe with flying cars.’ Gil Duran

Screenshot of CGI image found in the ‘From Crisis to Prosperity’ plan for a post-war Gaza.

Investigations by the Financial Times and a leaked prospectus from the Washington Post detail the GREAT Trust (Gaza Reconstitution, Economic Acceleration, and Transformation Trust): a US-administered, ten-year reconstruction plan for Gaza to become a tech-enabled Riviera, promoting ‘voluntary relocation’ for all Gazans. Trusteeship and relocation plans are cynical euphemisms for (neo)-colonialism and ethnic cleansing. The Gaza project involves the Boston Consulting Group, Tony Blair Institute (heavily funded by Oracle’s Tech Lord Larry Ellison), real-estate moguls like Steven Witkoff, Israeli-American venture capitalists like Michael Eisenberg, and former IDF Unit 8200 alumnus Liran Tancman, among others. This techno-utopia, powered by desalination, solar energy, and high-tech manufacturing, is portrayed as prosperity by some, by others a gruesome and potentially realistic dystopia: the true definition of techwashing.

Globalised Techwashing Against any Intifada

Israel’s Start-up Nation and progressivism is less a tale of entrepreneurial genius than a carefully curated myth designed to legitimise authoritarian militarism and neoliberal economic policies. But techwashing is not unique to Israel but a global strategy. Take Saudi Arabia’s US$500-billion NEOM project, branded as a futuristic eco-city and a beacon of innovation. Behind the glossy marketing lie mass dispossession and the death of tens of thousands of migrant workers: progress built on exploitation and repression. Or El Salvador, where President Nayib Bukele – recently re-elected, despite a constitutional prohibition – is building the first ‘Bitcoin City, arresting nearly 100,000 people in mass sweeps while proudly styling himself ‘the world’s coolest dictator’. ‘El Salvador’s governance model follows Bitcoin. It’s not a democracy, it’s a startup nation,’ declared Max Keiser, Bukele’s crypto-evangelist adviser. Here the authoritarian techno-turn is on full display: a digital utopia masking brute repression.

Even in countries that pride themselves on their liberal traditions, such as France, neoliberalism has dismantled the traditional left–right political axis. As Tariq Ali warned in The Extreme Centre, this vacuum becomes a springboard for authoritarianism. Here too, tech progressivism obscures material interests and enables dangerous alliances between capital and the far right. One striking example is Pierre-Edouard Stérin, a Christian-extremist billionaire and ‘tax exile’ who funds Macron’s Startup Nation while investing hundreds of millions through VC firms across Europe, and pouring €150 million into his ‘Pericles’ plan to bring the far right to power. His model? The US, where Silicon Valley has long fused entrepreneurial myth-making with reactionary politics. What he dreams of is nothing less than a ‘French Elon Musk’– a messianic entrepreneur who embodies profit, growth, and alleged Christian values. This is the epitome of techno-utopian aesthetics married to reactionary politics.

Innovation, in this framework, becomes both the means and the end of a global authoritarian revival. Technology is not neutral: it is a political project, inseparable from capitalism, militarism, and ethno-nationalism. Palestine has long been the compass of social justice struggles. Israel’s ‘Start-Up Nation’ is simply the clearest case study of how technology can be deployed to launder state violence, deflect criticism, and cement transnational fascist and far-right alliances. By unpacking how ‘progress’ is weaponised, we can begin to resist the seductive aesthetics of techwashing, and expose what lies beneath the shiny surface.

Technology creates the kind of mass society that echoes the definition of fascism – a world where citizens are absorbed, almost lobotomised, by a security-obsessed discourse and omnipresent techno solutionism. People do not merely endure the system, but participate in it, embracing technology as an all-encompassing, deeply political project. This technophile membrane legitimises both the actions of Big Tech and authoritarian policies. Progress and innovation are the glossy veneers, while human rights are pushed ever further into the background.

What we need is a collective wake-up call across civil society and social justice movements, but most urgently within the high-tech sector itself. Tech workers and users need to cut ties with Israeli firms and any companies complicit in genocide and reclaim the emancipatory promise of technology by returning to its roots: open-source, decentralised, committed to freedom and equality – not captured by the regimes that wield it to entrench domination and colonialism. Movements are already showing the way: Tech for Palestine, No Tech for Apartheid, No Azure for Apartheid, No Tech for Tyrants in the UK, Tech Workers Coalition in the US and Germany, and Tribe X in France. Their struggle points to the future. Our task is to join it.