Energy Transition Mythbusters: Myth #4 Decentralised energy will decarbonise and democratise the energy system

Topics

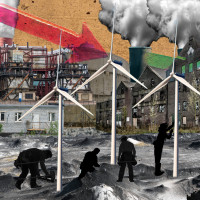

Localised, small-scale and community-led energy initiatives are often promoted as effective alternatives to decentralize and democratise the energy system. But, even though these projects play an important role in the energy transition, they are forced to compete in a for-profit energy market, limiting their impacts and real contribution towards the change. Here we debunk the fourth myth about energy transition.

Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Key takeaways

-

Decentralised energy will NOT decarbonise and democratise the energy system.

-

Decentralised energy initiatives such as community energy projects and municipal energy companies are undermined by the liberalised market environment. In the UK, when FiT subsidies gave way to competitive auctions, the number of new community energy organisations fall from 30 in 2014–15 to just one in 2017.1

-

Decentralised energy initiatives are not necessarily democratic. Community energy projects often exclude those without the money or time required for participation.

-

Decentralised energy alone will not deliver the energy transition. Rooftop solar PV has the potential to meet an estimated 18 per cent of the EU’s electricity needs, yet only if every single rooftop in the region that is solar compatible has a PV system installed. In Bangladesh, household solar generation became redundant as the government was able to provide more reliable electricity at lower prices.

-

The energy transition requires planning and coordination across scales. This calls for collaboration between public utilities, communities and governments on every level, alongside the wholesale democratisation of the sector.

The myth

The idea that ‘small is beautiful’, originating from economist E.F. Schumacher, is highly influential within the environment movement, which often advocates for more localised and decentralised ways of organising society.2 This line of thinking has become prevalent within energy transition debates. Herman Scheer, the architect of the German ‘Energiewende’, argued that the transition to renewable energy implies a more distributed and localised way of life, with households and communities able to power themselves through small-scale solar generation. This, for Scheer, was to be celebrated: by decentralising energy, he believed that we could decentralise political power and create more community-oriented and democratic political forms.

Scheer’s ideology of energy localism has filtered into the way that most actors – from environmental activists to government and industry – have come to think about energy transition. Generating energy from the sun, wind and water opens up new possibilities for energy production to take place at much smaller scales than large fossil fuel infrastructure allows for: every household can have a solar panel on its roof, every neighbourhood can operate its own wind turbine.

Myriad different forms of localised energy initiative are proposed. Local energy communities owned and managed as cooperatives by their members are often seen as key. Energy communities see people banding together – usually within a specific locality – to invest in and run energy technologies and infrastructures collectively.

Alongside local energy communities, municipal energy initiatives are also positioned as key players. Municipal energy schemes see municipal government playing a more active role in any system, either as grid owners or through municipal-owned companies that invest in renewable generation and/or provide energy to households and businesses. Moreover, individual households are often positioned as ‘prosumers’: producers of electricity through small-scale renewable generating assets, as well as consumers.

For some, the decentralisation of the energy system heralds the end of the centralised grid. As such, large incumbent utility firms tend to be portrayed as conservative industry dinosaurs standing in the way of the transition. Indeed, many argue that a more decentralised energy system would be inherently democratising, taking control away from industry giants and putting power in the hands of people directly through forms of localised community and collective control and ownership.

The reality

Decentralised energy has an important role to play in the transition towards more democratic and low-carbon energy systems. However, community energy schemes face substantive challenges when they are forced to compete in a for-profit energy market. In fact, serious questions can be raised about the democratic credentials of many decentralised energy initiatives due to the risk of exclusivity.3 What’s more, we need to be realistic about the limits of distributed generation in meeting climate targets: the transition needs to take place across a range of scales and large-scale forms of organisation and planning are more crucial than ever.

Decentralised energy is not necessarily democratic

Proponents of this myth tend to assume that localisation guarantees democratisation. In practice, matters are far more complicated. Decentralised energy in no way ensures more just or democratic outcomes within energy transitions. In many cases subsidy schemes geared towards supporting decentralised energy schemes such as FiTs have mostly benefitted wealthier populations able to afford large upfront investments such as rooftop solar panels. Meanwhile, lower income consumers have footed the bill for these subsidies through levies on their bills and taxation.8

The form of participation emphasised within community energy schemes is often financial, with people encouraged to invest capital to finance new community-owned generating assets. While financial participation has a role to play in democratising the energy sector, democratisation should not be reduced to this. Firstly, financial participation says nothing about decision-making power and control. In addition, it tends to be inaccessible to those on lower incomes -- often community energy schemes stipulate a minimum level of investment out of reach to those on low-incomes. Ultimately, democratising the energy sector means ensuring that all can participate on an equal footing, irrespective of ability to pay. If financial exclusion is one risk of community energy, another is that participation in community energy schemes tends to require time and energy that tend to be in short supply for those living more precarious lives, as well as people with caring responsibilities.9

Decentralised energy alone will never be sufficient for decarbonisation

Decentralised energy can certainly play a significant role in low-carbon transitions. However, this role will likely remain relatively modest.

For example, Amsterdam and Barcelona have both created roadmaps to boost their own energy production, which face very real challenges.10 It was estimated that if all usable surfaces within Amsterdam were to have solar panels installed, the city would be able to produce around 1.1 GW through solar. While this is an impressive amount, it is still only around 30 per cent of the city’s estimated electricity needs by 2030.11

Barcelona has also made considerable steps towards a renewable transition, and in 2019 established a municipal energy company to help achieve maximum local energy generation.12 However, even if full capacity for city-wide solar installations was reached, Barcelona’s rooftops could only produce an estimated 1,191 GWh per year, accounting for only around 8 per cent of the city’s current total energy needs.13

The case of Bangladesh also illustrates the shortcomings of distributed renewables. Here, household solar systems grew widely between 2003 and 2018, electrifying 16 per cent of rural households.14 Yet by 2021, the rate of new solar installations had fallen to almost zero. This was because the government stepped in to provide more reliable electricity connections at lower prices.15

These cases indicate that decentralised renewable generation is unlikely to be remotely sufficient for meeting current energy needs, even under full-capacity deployment. Indeed, a recent paper by TUED estimated that rooftop solar PV has the potential to meet just 18 per cent of the EU’s electricity needs, and only if every single rooftop in the region that is solar compatible has a PV system installed. Given that this level of ambition across the EU seems implausible, the figure is likely to be a lot lower, highlighting that relying on distributed generation alone is unfeasible.16

Solar panel/rspata/Pixabay

Decarbonisation requires planning and coordination across scales

It is clear, then, that small-scale distributed renewable energy cannot deliver on energy transition alone. A rapid and effective transition will require thought and practice across a range of scales, with a pivotal role remaining for large-scale centralised infrastructure.

For one thing, the transition that is needed calls for a rate and depth of infrastructural change that can only be achieved through centralised planning. In addition, the technical challenge of the variability of renewable energy requires the capacity to coordinate diverse forms of generation across multiple locations. Accountable centralised grid infrastructure is more important than ever.

This does not mean we must return to the top-down state industries of yesteryear. Nor does it mean conceding power over the transition to private utility firms. The vision of Trade Unions for Energy Democracy and TNI has comprehensively reclaiming public utilities at its heart. Our agenda includes municipalities forging cooperative partnerships with utility firms that are under democratic public ownership and that adopt a public goods rather than profit-based approach. In Denmark, public-public partnerships of this kind between public utility firms, municipalities and co-operatives have driven one of the most advanced energy transitions in the world. In Costa Rica (see below), a publicly planned, owned and organised electricity system has enabled the country to fully decarbonise its power provision.17

We need public-community collaborations across scales

The question is not whether decentralisation or centralisation will deliver the energy transition, but rather how public and community actors can collaborate across scales in ways that prioritise the public good over private gain.

The neoliberal energy model imposes unnecessary challenges to the renewable transition. Instead of an environment where electricity utilities and decentralised energy producers are encouraged to work together to solve the challenges, they are instead stuck in an environment of profit-seeking and competition. Rather than being forced to choose between decentralisation and centralisation, fixing the failure of energy liberalisation and privatisation requires nothing less than reclaiming energy systems from the market to build an overarching publicly owned energy sector that is accountable and democratic, with ample room for community initiatives. But if countries continue to rely on free markets, decentralisation may actually strengthen, rather than challenge, the for-profit energy system.

In order to truly ensure universal access to clean energy, the focus should be more on democratisation than on decentralisation. Take the community constructed, owned, managed and operated micro hydro power plants in El Cua, Nicaragua. Here, energy is regarded as a right that should be affordable for everyone. Members’ financial contributions are based on their income, rather than a price per kWh, as this would limit access for poorer households.18

By prioritising democratisation, the right to energy can be achieved on a larger scale. Costa Rica is home to four large rural electricity cooperatives, owned and run by their users. These not-for-profit cooperatives take part in setting, developing and enforcing public policies in rural communities.19 Altogether, these cooperatives cover a fifth of the national territory and supply power to over 390,000 users.20 Electricity coverage in Costa Rica is 99.9 per cent because cooperatives do not have to complete with but operate alongside the state-owned electricity utility ICE, alongside several sub-national public companies.21

Democratisation can increase accountability and is key to effectively interlink decentralised initiatives with larger-scale energy production and vice versa in order to achieve clean energy for all.