Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Why does popular support for Palestinian rights often fail to generate impactful solidarity? This article explores Sudan's intersecting struggles with Palestine, examining metaphysicalisation, Black-Arab solidarity tensions, and the global attention divide to uncover effective paths towards liberation.

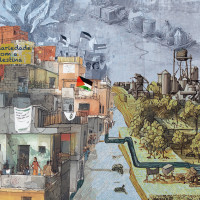

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

اننا نخذل فلسطين عندما لا ندرك مغبة العزلة التي تفرضها علينا الرأسمالية المالية الصهيونية العالمية القبلية بمغبة التماهي مع لغتـ[ها] دون ان نجود لنا فنبدع لغة تخصنا نحارب بها ونواجه بها خصومنا العالميين والداخليين"

‘We fail Palestine when we do not comprehend the consequences of the isolation forced on us by the global tribal Zionist financial capitalism, itself an outcome of assimilating [its] language without creating and developing our own language with which we can face our global and local enemies.’

Metaphysicalisation of the Palestinian Struggle

The 1989 coup in Sudan initiated the 30-year presidency and regime of Omer Al-Bashir. While many of the characteristics, slogans, alliances and key figures of this regime changed over the years, one thing remained constant: the regime’s narrative about its relations with the West (even as those relations themselves changed). The coup’s leaders presented their political project as one of revolutionary Islam engaged in a battle with a Christian West that aimed to limit the expansion of Islam.4 The regime used this narrative to cultivate popular support, and to justify both the decisions made by the regime and the challenges it faced. According to this narrative, protests and civil disturbances—armed or not—were not a reaction to uneven and unjust development and economic suffering but constituted opposition to the Islamic project by movements supported by the West.

Such an approach is not alien to Sudan and the region, it is in fact rooted in the post-colonial nationalist era, which prioritised abstract concepts like national pride and state sovereignty over people-centred goals such as self-governance and equitable resource distribution. These concepts were often used to mask the failure of post-colonial governments to improve the lives of the majority, with the same approach adopted by religiously based political projects following the decline of pan-Arab ones.

The Sudan regime’s position with regard to Palestine was one part of this general approach. Al-Bashir’s government declared early on its opposition to any normalisation with the Zionist occupation, and it harshly criticised the Oslo Accords and accused Arafat of straying from the principles of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).5 At the same time, the Sudanese government continued to acknowledge the PLO as the official representative of the Palestinian people, which maintained an embassy in Sudan, and hosted offices of several Palestinian organisations and resistance factions. This relationship continued throughout the following decades, with some fluctuations. During this period, Israel declared Sudan a ‘terrorist state’ in official statements, citing its hosting of the Palestinian resistance as well as the country’s role in providing weapons to resistance groups. These allegations were used by Israel to justify a number of Israeli bombings inside Sudan, including strikes in 2009 and 2011 on convoys of trucks said to be carrying weapons to Hamas, as well as the 2012 bombing of the Al Yarmouk weapons factory owned by the SAF. In response to the latter, Sudan’s ambassador to the United Nations (UN) complained that ‘Israel was the main factor behind the conflict in Darfur’.6

Presenting Zionists, and the West more broadly, as the hidden players behind all of Sudan’s problems was a tactic that was frequently used by Al-Bashir’s government, and the latter often accused opposition parties of receiving support from the West and Israel, to discredit them. On the other hand, marches in support of Palestine that ended with a speech by the president were the modus operandi used to galvanise support for the government. These speeches equated animosity towards the ruling regime, internal or foreign, with animosity towards Islam. Importantly, the narrative put forward in such speeches did not include a serious presentation of the Islamic state-building project, or its dissimilarity to Western projects – and to the Sudanese opposition’s projects – which would enable citizens to assess the relative advantages and disadvantages of these contrasting approaches and deduce any material bases of the animosity between them. In this way, the regime moved discussion of the Palestinian struggle to the realm of the metaphysical/religious—or at best that of identity politics.

Within the Sudanese political scene in the past three decades, there was no significant alternative narrative to that put forward by the Islamists, in support of the Palestinian struggle. The topic was to a large extent abandoned by the left. In the case of the Sudanese Communist Party, this abandonment was one as part of the general theoretical and material decline suffered by the party following the severe measures taken against it in 1971 by the military government of the time. The degree of decline of the party’s pro-Palestine efforts in the following decades was such that when the TGS carried out its normalisation efforts in 2020, the party, seeking to show its opposition to this process, had to go back to paragraphs from its literature from the 1960s for proof of such a position, prior to its years of decline. More generally, the abandonment of the Palestinian cause by left and other groups meant that in 2020 it was only the recently toppled Islamists that had the capacity to create a limited anti-normalisation protest movement. This allowed the TGS to characterise all opposition to its foreign policy as dogmatic—in a manner reminiscent of the old regime’s tactic outlined above—and to contrast this dogmatic opposition with the new TGS government’s ‘courage and commitment to combating terrorism, building its democratic institutions, and improving its relations with its neighbours’.7 The arguments made by the Islamists and the TGS thus fed off each other.

The metaphysicalisation of the Palestinian struggle, i.e. the process of transferring the Palestine question to the realm of the metaphysical/religious, is a tool used by different systems and governments that seek to steer people away from a material discussion of liberation and freedom. It limits the capacity of Palestinian solidarity movements within Muslim majority countries to engage in genuinely emancipatory efforts. Such efforts would address the Palestinian cause as an issue of a population’s right to its land and resources. This would, in turn, enable substantial solidarity, and at the same time the form of material links to the struggles of other oppressed populations.

It is worth mentioning here that metaphysicalisation is also a useful tool for the Zionist project in regard to galvanising religion-driven internal commitment, as well as external support. It is entirely logical that such a tool, which tends to distort the reality of the Palestinian struggle, can be of great benefit to Zionists, as it disguises important facts. And it is similarly logical that this tool can have negative effects on the oppressed, as it disconnects solidarity and alliances from the material reality of their suffering and their struggles.

The popular pro-Palestine movement that has arisen in the global North since October 2023 is largely based on people’s rejection of the livestreamed crimes being inflicted against Palestinians as human beings. On this basis, it has unsurprisingly popularised and promoted narratives that explore connections between Palestine and other ongoing injustices and struggles, such as those in Congo and Sudan. This has, in turn, led to rejection among many people in the global North of the existing imperial political and economic setups, and has reignited discussions about the colonial and neo-colonial policies of their governments. It is important to note that similar narratives and connections are not made with the same frequency or coherence in areas which have historically shown strong support for Palestine, such as Muslim majority countries. Within these areas, Sudan included, solidarity with Palestine is, by contrast, generally tied into existing metaphysical rhetoric about conflict between Muslims and infidels. This approach is given succour by the narratives advanced by pro-Zionist media organisations, politicians and intellectuals in the global North which emphasise a global North–Israel alliance set against a global South–Palestine alliance, presented as a clash between democracy and terrorism. This framing echoes the dichotomy of civilised versus uncivilised nations advanced during the era of direct colonisation up until the middle of the twentieth century. This framing advances a culturalist understanding of the Palestinian struggle: it is mixed with Islamophobic sentiments and it disconnects that struggle from the reality of the political and economic interests that are involved. In line with this metaphysicalisation, public opinion in Muslim majority states deprioritises positions which do not align with the cultural groupings of nations, such as the lack of substantive support provided to the Palestinians by the governments of Muslim majority states, the mass protests in support of Palestine taking place in global North countries, as well as the official support for Palestine from governments in the global South outside of the Muslim world.

This deprioritisation can be explained by the lack of an alternative and coherent framework for critically exploring the political and economic interests of, for example, the governments of Muslim majority countries, and how they relate to, or contradict, the interests of the populations of these countries. The absence of such a framework in public discourse leads to a failure to identify interests shared with oppressed populations that are outside of the cultural grouping.8

Is the critical task of the Sudanese left to supply this deficiency, by providing a progressive and emancipatory analysis of the Palestinian struggle. Unfortunately, this crucial task has thus far largely been abandoned in Sudan, perhaps due to the assumption that the public is already aligned with the right side of the issue. However, recent history reveals that even the most righteous positions, when not founded on a solid material analysis, are vulnerable to manipulation by opportunistic, self-serving propaganda. This is apparent in Sudan’s recent history. After decades of rule by a dictatorship that heavily relied on Islamist propaganda, following its overthrow in the 2018 revolution under the slogan ‘freedom, peace and justice’, different counter-revolutionary forces weaponised the question of solidarity with Palestine for their own benefit (as previously discussed). Thus, the forces of the old regime presented the Palestinian cause as an Islamic struggle (metaphysicalising that cause), and they framed the new government as an anti-Islamic regime, citing its policy of normalisation with the Zionist occupation. In the simplified framework of Muslims versus infidels, this justified a call for the return of ‘Islamic rule’. At the same time, counter-revolutionary forces within the new transitional government sought to control and limit revolutionary sentiments and critical debates about its policy, and so they painted solidarity with Palestine as a dogmatic remnant of the ousted regime. While both of these counter-revolutionary narratives fed off each other, a progressive and revolutionary solidarity discourse was missing. Established left-leaning parties failed to present and defend a revolutionary position, for a number of reasons, including their involvement in the counter-revolutionary alliance of the transitional government and their abandonment of the question of Palestine to the Islamists. In regard to the new forces of the revolution, whether the resistance committees or within the general public, these were strongly impacted by the propaganda of the TGS, which equated itself with the revolution, which made it difficult for them to criticise the TGS’ policies, normalisation included. Thus, although there were some rhetorical gestures and small initiatives in support of Palestine among the forces of the revolution, they failed to adopt a substantial and coherent revolutionary narrative on the issue.

The control of the metaphysical framing of the Palestinian struggle was beneficial for the counter-revolutionary forces, whether those standing for Palestine or against it. This provides a clear example of how the lack of a revolutionary, materialist analysis deprives individuals and communities of the opportunity to develop a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the interconnected systems of oppression, let alone the ability to overcome and replace those systems.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Black Solidarity Versus Arab Solidarity

As the genocide of Palestinians by Israel continued following October 2023, conflicts also escalated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), leading to calls from activists both within Africa and within African diaspora communities to prioritise and address the struggles of people in the DRC.9 These calls emphasised that the plight of the Congolese people, much like the Palestinians, requires immediate attention and solidarity from the international community. While most activists aimed to draw parallels between the two struggles, underscoring the shared experiences of oppression—and even the involvement of the Zionist regime in DRC10—some voices called for abandoning the Palestinian cause and focusing instead on Black struggles. Similar calls have been present in the Sudanese political scene for a few years.

The Arab–Black dichotomy has been used by various political players inside and outside Sudan to simplify Darfur's conflicts since the early 2000s. This narrative extends the Muslim–infidel dichotomy advanced by previous Sudanese governments, including Al-Bashir's regime, during the South Sudan war. Unable to exploit religion in Darfur, where the population was mostly Muslim, Al-Bashir's regime shifted to emphasising ethnic identity instead. This narrative drew on the story of origin adopted by the populations of the privileged centre, who see themselves as the descendants of Arab immigrants to Africa.

The Sudanese state has historically been very centralised, with successive elitist governments since the country’s independence pursuing minimum development and violent rent seeking for the majority of the country, while preserving relatively higher levels of development in the capital Khartoum and surrounding areas. This strategy helped create a privileged minority who were invested in maintaining oppressive structures. Such a setup was an expected result of colonial state building and led to the evolution of an Arab supremacist narratives out of the story of origin adopted by the country’s privileged center. It was this narrative that the regime used to dehumanise Darfuri victims and shape public opinion in the centre, including by focusing its propaganda on incidents that reinforced this ‘othering’ of the Darfuri population.

Thus, when faced with accusations by international organisations of war crimes in Darfur the regime chose to rely on identitarian talking points. In response to the accusations made by the Save Darfur Coalition, for example, the Minister of Information stated in an interview in 2007 that ‘The Darfur issue is being fuelled by 24 Jewish organizations’,11 referring to American Jewish organisations within the 190 members of the coalition. The coalition was widely criticised by activists and scholars for its simplification of the Darfur conflict, including adopting the Black versus Arab narrative,12 but such criticisms were inconvenient for the regime as they focused attention on factors such as resources and land grabs.

On the other side, the same narrative (Black versus Arab) was also occasionally used by the Darfuri opposition, both to galvanise their base as well as to justify some of their political decisions. For example, in 2008, the Darfuri rebel group the Sudan Liberation Movement opened an office in Israel. This move was linked to the fact that Darfuri refugees often fled to occupied Palestine as a route towards Europe. Though it was controversial and unpopular, supporters justified this by framing Palestine as an Arab struggle, and Darfur's conflict as an Arab versus Black conflict. This led to arguments in favour of prioritising Black interests and justifying animosity toward Arabs. Ironically such justifications ignored the history of liberation movements and independence governments in Africa in the 1960s and 1970s, which strongly opposed the Zionist regime, which they equated with the Apartheid regime in South Africa.13

The Black versus Arab narrative provides fertile soil for the propaganda of various reactionary forces, including the Sudanese regime. For example, it allowed the Al-Bashir regime to cultivate public support for the idea that the conflict was mainly related to inherited ethnic divisions, and thus that it was to be expected that each side of this ethnic division would seek to dominate the other. A very different political project would have been generated by a material and class analysis of interests and resource distribution shaped by and shaping aggression against the population in Darfur. Such analyses were present in academic research,14 and even in the official positions of some political parties. For example, the Sudanese Communist Party often referred to issues relating to resource distribution issues and the politics of land utilisation as important factors behind the war in Darfur. However, analyses like this were not prioritised by the major opposition coalitions . These coalitions included parties from the representatives of agricultural and trading capitalists to the communist party, justified by the later by their commitment to a “national front” including the “national capitalists”. Involvement in such coalitions factored in limiting the ability of the communist party to push for economic justice projects and bring forward analysis that captures public imagination and support. In the absence of a revolutionary materialist analysis, the majority of public opinion subscribed to—or at least tacitly accepted—the Black versus Arab narrative. The results were destructive, not just in regard to the position of politically engaged Sudanese towards the Darfuri struggle, but also to Sudan’s ability to move towards justice and peace.

Ethnic narratives also provided a strong basis for the representation politics later adopted by the TGS, such as the highlighting of the racial identities of cabinet and sovereign council members in order to avoid addressing the root causes of the injustices affecting Darfur and other marginalised areas. Ethnic narratives continue to be advanced in the military mobilisations and propaganda employed by both sides of the ongoing war between the SAF and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

By contrast, Sudanese revolutionaries have repeatedly challenged identitarian propaganda. When the Al-Bashir regime sought to utilise ethnic tensions for its benefit, by accusing ‘Darfuri cells’ of being behind the protests in 2018, protesters responded by chanting ‘the whole country is Darfur’. As the revolutionary front evolved, such emotionally charged chants were translated into specific and documented political projects and charters. The Revolutionary Charter for Establishing People’s Powers, which was issued by over 8,000 neighbourhood resistance committees across Sudan in February 2023, conceptualises the conflicts in the country as being the tool of an elite that seeks to profit from displacement and engage in resource grabs, and as a product of the war industry itself. The charter explains that elites use ethnic tensions to advance identitarian differences and justify their wars for resources, and it draws a direct link between national profiteering from wars and the participation of Sudanese forces in regional conflicts in Yemen and Libya, also for profit. By adopting this narrative, Sudanese revolutionaries challenged historical counter-revolutionary frameworks that perpetuate injustices.

However, the recent conflict in Sudan, and the resurgence of identitarian propaganda, have disrupted these revolutionary efforts. Some Sudanese and diaspora activists are now reviving identitarian narratives in response to the current war in Sudan and global indifference to it, which they attribute to Sudanese Blackness, echoing sentiments of Afro-pessimism that originated in the United States. It can be argued that the normalisation of African suffering over the past century has contributed to the lack of attention given to Sudan's current war, as well as its past conflicts, poverty, and famines. conflict in the Middle East has also been normalised, and that before 7 October 2023 this had led to apathy towards the situation of Palestine under Zionist occupation. However, in the case of both Sudan and Palestine these are not the primary factors behind global attention—or the root causes of the suffering there. Rather, geopolitical factors largely determine how much attention different global South struggles receive in mainstream media and public engagement. In Sudan, protests against impoverishing neoliberal economic policies were celebrated by international mainstream media when those policies were imposed by Al-Bashir’s regime (considered an enemy of the global North), but they were ignored by the same media when the policies were imposed by the TGS (a puppet of the global North). The attention given by activists and allies to Sudan was accordingly impacted, since mainstream media significantly controls the narrative and access to information.

Narratives that normalise atrocities are tools of the counter revolution employed by those who benefit and profit from those atrocities, to minimise the potential of global revolutionary solidarity. Mistaking these tool of the counter-revolution for a framework of revolutionary analysis does more harm than good, in terms of realising revolutionary goals and eliminating the suffering of the people. Sudan’s recent history thus reveals that resorting to ethnic narratives leaves political movements and the public vulnerable to the reactionary analyses of oppressive governments, rather than fostering emancipatory approaches and principles locally—let alone struggles that go beyond political borders.

Injustices Competing for Airtime

In April 2023, war erupted between two long-standing partners, the SAF and the RSF, which had previously jointly constituted the military half of Sudan’s transitional government. In the months that followed, the conflict devastated Sudan’s cities, beginning with the capital, and resulted in thousands of deaths and the displacement of millions of Sudanese. Over subsequent months, news networks in the Arabic speaking region covered the fighting extensively, introducing viewers to Sudan at an unprecedented level, and the lack of familiarity with the country was clear in the repeated mispronunciation of the names of Sudanese cities and streets by the regional news anchors.

Sudan became the main news, this meant its updates were repeated more often taking the lion share of airtime, it gotwith major channels showing infographics and city maps. Sound bites from interviews with Sudanese politicians were recurrent segments in programmes with high viewership.15 For months the Sudanese public were overwhelmed by news products reflecting the ethos and methods of information systems and organizations that prioritize reach and interaction to actual informative content.

However, less than six months after the SAF–RSF war broke out, the Zionist regime launched its brutal attack on Gaza in a mass punishment campaign following the Palestinian resistance’s Al-Aqsa Flood operation. Gaza instantly became the main news item in regional networks, the largest of which—Al-Jazeera—dedicated 24/7 coverage to the subject on its main Arabic channel. In a model of news for maximizing reach, the only translation possible of the importance and weight of the mass killing campaign in Gaza was full day coverage of repeated continuous updates, infographics and analysis of the battlefield by former military personnel.

Although this continuous coverage provided a counterweight to the Zionist propaganda appearing in Western media, and their denial of the occupation’s crimes, this model of news to maximise reach has dangerous flaws that must be addressed. And while it cannot be expected that mainstream channels will provide the type of journalism necessary for a popular revolutionary political project, it is important to analyse where this mainstream model falls short, in order to imagine and develop what we might call ‘revolutionary journalism’. The mainstream news model, which aims for maximum reach, is not capable of providing information on injustices that do not fit the breaking news mould, such as the reality of life under the occupation, nor of substantially addressing how the Zionist occupation weaponised its control of crossing points between different areas of occupied Palestinian land, both before and after October 2023. In addition, revealing the details of this reality would involve exposing the complicity of regional regimes in allowing and facilitating the suffering of Palestinians. Furthermore, the news for maximum reach model offers no space for informative analysis and investigation of tools at the international level for holding the Zionist occupation to account, or of which countries and businesses trade critical goods with Israel (which would be of great benefit to the popular boycott movement in the Arab-speaking region). Likewise, this model shows no appetite for documenting and highlighting organised popular efforts by Palestinians and allies to lessen their suffering under the occupation via creative funding methods, innovative utilisation of telecoms, and popular initiatives to break the siege on Gaza. Again, depicting effective popular efforts of this kind would develop viewers’ sense of people power and ignite ideas about what they can do to support the Palestinian struggle. In order to obtain such information, viewers must instead rely on individuals’ social media accounts, rather than large and well-funded news channels with hundreds of journalists on their payroll. Indeed, the model of breaking news for maximum reach capitalises on people’s sense of despair and sadness, instead of fostering informed, organised and effective popular movements in support of Palestine.

The regional news coverage of Gaza since October 2023 is not very different from the coverage of Sudan in previous months, although it is on a much larger scale. Since this mainstream news model is incapable of, and uninterested in, informative nuanced coverage that can provide appropriate weight to multiple concurrent events that are worthy of mass attention, it pits different struggles around the world in a competition for airtime and newsroom attention. Thus, overnight, the Sudanese public witnessed a dramatic drop in the quality and quantity of updates on their homeland, to the extent that infrequent programmes dedicated to news about Sudan started to be advertised as coverage of a forgotten war. One effect of this dropping off in airtime and quality is that propaganda from both the SAF and the RSF has been able to flourish: for every incident and development, from takeovers of cities and mass killings to negotiations and summits, two narratives (if not more) are now presented. Even the matter of which party is in control of which geographic location is debated, when this could easily be investigated and reported on if minimum serious journalistic efforts were applied.

Professional, revolutionary, people-centred journalism is a necessary foundation for discussions and actions that can significantly advance revolutionary projects. This holds true for both the liberation of Palestine and the pursuit of justice-driven peace in Sudan. Such journalistic efforts would seek to present and prioritise facts that have a profound impact on people’s lives, and would provide the public with an adequate understanding of these impacts. Rather than relying on anecdotes and repetition that is designed merely to create trends and increase interactions, revolutionary journalism would offer in-depth, meaningful insights and highlight grassroots efforts that sustain lives: for example, the development of communal service provision in Sudan through communally managed kitchens, health facilities, shelters, and education programmes. The emphasis would not be on stories of individual heroism but on noteworthy experiences of organising. Revolutionary, people-centred journalism is essential for accurately informing and documenting revolutionary organising efforts. It would provide a true representation of reality and would focus on the priorities of the public, rather than the obfuscations advanced by elitist media. Additionally, this type of journalism would facilitate the exchange of lessons and analyses within international revolutionary efforts, enabling their evolution into a cohesive and necessary international revolutionary front: not only informing the public but also fostering a sense of solidarity, people power and shared purpose across global revolutionary movements.

In the present situation, where revolutionary journalism is rare, the logic of capitalising on trends unfortunately spills over into advocacy and solidarity activities globally. In the case of Sudan, this is evident in the activism of the Sudanese diaspora. Groups that are desperate to gain attention for the struggles of their people and urgently desire to bring an end to their suffering see ‘trendifying’ Sudan as the shortest path towards those goals. This includes attempts to fit the Sudanese struggle into the shape of the Palestinian one, by portraying Sudan as being occupied by the RSF (supported by the United Arab Emirates (UAE)) in a manner akin to the Zionist occupation. This approach prioritises spotlighting RSF crimes while ignoring SAF ones, and leads to calls to end support for the RSF, rather than delegitimising all parties that seek to obtain and retain power through aggression and violence.

This spotlighting of RSF crimes is not disconnected from historical frameworks that provided bases for the success and virality of these narratives among Sudanese public opinion. These frameworks include the historical marginalisation and othering of Sudanese citizens from the western areas of the country, as previously discussed. Since most of the RSF forces, including its core, are from western Sudan, it is possible to frame them not just as criminals or rebels but also as invaders and occupiers (just like the Zionists). But this is an inaccurate definition, to say the least. Another framework that is crucial to the success of such narratives is that of protecting the state, which is equated with protecting the official army of the state (which is engaged in confronting the RSF), instead of protecting the people (in the face of both criminal warring parties, and other counter-revolutionary forces). This framework is based on a long history of state propaganda and weaponisation of the slogans of patriotism to obtain support for the ruling class which controls the state. (Sudan is not unusual in this: such a framework is present in almost all modern states.)

This shortcut in regard to bringing attention to Sudan is a path leading in the wrong direction, in both the short and long term. Even the most positive scenario regarding the result of such an endeavour is that it will succeed in cutting of all support to the RSF, thereby paving the way for authoritarian military rule with minimum accountability for those enacting violence in the name of the state.

Thus, despite the importance of studying the predatory role of the UAE government in the region, the tendency to present it in the Sudanese context as a supporter of an occupying force similar to the Zionist project leads to mistakes that are fatal for the revolutionary project. For example, it leads to disregarding the important internal factors that led to the creation of the RSF and other militias: the ability to recruit members of such militias is the result of historic and continuous land grabs and resource takeovers which have victimised marginalised communities within Sudan.

The short and trendy path to bringing attention to Sudan will therefore do long-lasting and significant damage to the potential for revolutionary organising within Sudan, which can only be built on the strong foundation of an accurate representation of all injustices faced by different communities in the country, and beyond. Similarly, the approach of reducing information on the Sudanese or the Palestinian struggle to the breaking news format, despite its limited short-term success, in fact damages the possibilities for developing nuanced and evidence-based forms of solidarity, even among sympathetic audiences and principled allies. Such revolutionary solidarity can only be supported by revolutionary journalism.

Revolutionary Solidarity

Highlighting the importance of a revolutionary approach to solidarity with Palestine, Sudanese socialist researcher and author Khadija Safwat has brilliantly stated: ‘We fail Palestine when we do not comprehend the consequences of the isolation forced on us by the global tribal Zionist financial capitalism, itself an outcome of assimilating [its] language without creating and developing our own language with which we can face our global and local enemies.’16 Recent Sudanese experiences include an abundance of evidence on the dire consequences of adopting counter-revolutionary language and tools, even if they may be useful in the short term. From the language of identity politics to the tools of capitalising on trends, pragmatic approaches that are void of revolutionary material analysis have weakened the Sudanese resistance project internally, and have equally weakened its ability to support the Palestinian struggle.

The task of clarifying the revolutionary language and tools of solidarity is urgent and essential, and should not be abandoned in the search for quick gains. It is a continuous task that requires employing a critical lens throughout our analyses of injustices and in developing strategies of resistance. Within the intersections of the Sudanese struggle for justice and the Palestinian struggle for liberation, employing such a lens would have elevated discussions around the TGS’s normalisation with the Zionist occupation above identity politics and confused definitions of modernisation and progress, instead promoting discussions of what the Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin17 called the two legs (one economic and one political) of the imperial project. Sudanese normalisation with the Zionist entity was a case of these two legs working in harmony, in full public display, being almost a caricature in the vulgarity of its transactional nature: linking the utilisation of international monetary tools (the economic leg) to advancing the political leg of colonial interventions in Palestine. In the case of defining the shared struggles of the Sudanese and Palestinian populations, and the events that led to the simultaneous increase of their suffering in 2023, a critical revolutionary lens and language would also highlight issues such as the impact of legitimisation by the international community of criminal forces (the colonial state of Israel in Palestine and military rulers in Sudan), and its role in undermining popular resistance actions. This would be both a coherent approach as well as one that could help unite several oppressed groups across the globe around the issue of accountability in regard to international diplomacy, and a radical change to its structures.

A small but significant example of such an approach occurred following the coup by the military council in Sudan in October 2021. At this time, the UN mission in Sudan initiated efforts to re-legitimise the coup leaders by fostering negotiations to form a new governing structure for the country, with the participation of the military council and the civilian partners in the TGS, at a time when there were daily protests against the coup and any form of military rule. The UN mission attempted to persuade the resistance committees to join the negotiation meetings, given their popular legitimacy, which was apparent in the size and organization of the protests they led. After repeated requests, which they rejected, the resistance committees finally accepted to attend a meeting – on the condition that the meeting be livestreamed on Facebook. The committees clearly understood that secrecy promotes corruption and reduces public engagement, and thus they sought to ensure transparency. The UN mission rejected the resistance committees’ proposal and cancelled the proposed meeting, in effect admitting that their approach was not transparent or in line with the interests of the general public, from whom they sought to hide the political reality. This proposal by the resistance committees, and its success in exposing the nature of the UN mission and the process it promoted, was the result of a principled commitment to the rights of people to information and political participation, being based on an understanding of the impact of public participation in the balance of power against the elite, and reflected a creative use of the available technological resources.

The history of the Palestinian struggle also offers an example of how transparency and access to information can support a revolutionary project. It is often forgotten that the involvement of the Western colonial powers in the creation of the colonial project in Palestine only became known thanks to the revelation of the text of the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement by revolutionaries in Russia following the October 1917 revolution. To this day, the publication of this significant document provides strong evidence in support of revolutionary arguments against the colonial practices of the global North.

Both of these examples reveal that transparency and accountability are valid and efficient weapons against the counter-revolutionary weaponisation of secrecy in global diplomacy (usually justified under the vague slogans of national security and the protection of state secrecy). They also reveal that practical manifestations of transparency and accountability depend on what is possible at the time, and that efforts to achieve transparency and accountability vary by context. In some countries they may involve pushing for the release of funding details and diplomatic communications, while in others they might focus on highlighting overlooked public information. Understanding these limits requires informed, engaged debates that are rooted in principled analysis and global revolutionary solidarity. It is important here to remember that such attempts have a better chance of succeeding when they are implemented within revolutionary political organisations, rather than by individuals with no organisational links.

Within Sudan, a revolutionary project that is committed to a material analysis of issues within and outside of the country’s political borders is necessary and would be beneficial. And while some have argued that the revolutionary project should be foregone in favour of the short-term priority of ending the current war, only a revolutionary project can bring about that aim and build a justice-driven sustainable peace in the country. Such a project would involve, for example, developing the current efforts to provide communal services, which are presently helping the Sudanese population survive the war, into new sustainable systems of communal control over resources and decision-making. This will improve lives in the short term and create conditions for the growth of bottom-up people power and just distribution of resources, eliminating the spaces available for elitist armed forces and the root causes of war over the longer term. International progressive allies of Sudan should employ a similar approach of revolutionising their methods and analysis, using the spaces for political activism that are available to them to increase the likelihood of revolutionary progress within the suffering communities. The aforementioned proposals with regard to promoting revolutionary journalism, and transparency and accountability within international diplomacy, are examples of other solidarity actions that can benefit both the Sudanese and the Palestinian resistance movements—among many others around the world.

The struggles of Sudan, Palestine and other oppressed populations must be addressed by revolutionaries using tools and language that are aligned with revolutionary principles, not those imposed by oppressors. Revolutionary frameworks reject hierarchies of struggles and competition for global attention, and emphasise that freedom and dignity are universal rights, and that the existence of any oppressive regime threatens the success of all revolutionary movements. All oppressive regimes utilise similar tools against the popular resistance they face, and they use the power they accumulate in one geographic location to cement systems of oppression that are beneficial to them in other areas of the world. However, this does not mean that oppressive systems always mirror each other, or that they have direct connections—so our revolutionary understanding should not be limited to searching for hierarchal or conspiratorial links between struggles. In fact, a revolutionary material analysis should be based on revolutionary principles and a contextualised understanding of every struggle, and should seek to develop adequate tools to improve the material reality of the oppressed communities in the present, while laying the foundations for new systems for the future.

Revolutionary solidarity must therefore not eschew quick gains, but should be capable of weighing the impact of short-term changes against the success of the long-term revolutionary project: it is a solidarity that is committed to actions that serve both in a dialectical way. And revolutionary solidarity understands that failing one will fail both, as well as undermining the potential for liberation and revolution globally.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

-

Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

Publication date:

-

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

Publication date:

-

Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Publication date:

-

Sustainability fantasies/genocidal realities Palestine against an eco-apartheid world

Publication date:

-

Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

Publication date:

-

From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024

Publication date:

-

The circus of academic complicity A tragicomic spectacle of evasion on the world stage of genocide

Publication date:

-

India, Israel, Palestine New equations demand new solidarities

Publication date: -

Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation

Publication date:

-

From the Favelas and Rural Brazil to Gaza How militarism and greenwashing shape relations, resistance, and solidarity with Palestine in Brazil

Publication date: