Power-off Lessons from the struggles against Big Oil

Big Oil has been the target of activists for more than two decades as the principal blockage to effective climate action. TNI interviewed two leading climate activists and researchers involved in the campaign against French multinational Total for their assessment of the campaigns and the possible next steps.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Olivier Petitjean is a journalist and co-founder of the Multinationals Observatory (Multinationales.org) set up in France in 2013. He is a specialist on corporations and lobbying. Clémence Dubois is the Associate Director of Global Campaigns at the global climate activist network, 350.org. Both are involved in the French campaign to StopTotal. The Multinationals Observatory and 350.org co-published a report in December 2023, TotalEnergies - This is what a phaseout looks like, which explored options for regaining control over Big Oil and how states could rapidly phase out fossil fuels within a ‘just transition’ framework that is democratic, transparent, and inclusive.

What are the principal sources of Big Oil’s power – and how are they seeking to maintain it?

Olivier: The source of their power is partly the same as for any other global corporations – money, resources, close connections with governments, and a great ability to join forces to defend their common interests – but they have much more of all that than almost everyone else.

Their power is also the result of decades of privatisation, liberalisation and pro-business policies that have deprived governments of whatever control they might have had in the past on national energy, markets and prices, and of whatever capacity they might have had to conduct the energy transition directly, without depending on big corporations. As a result, many governments have been left with seemingly no alternative but to accept Big Oil's slogan that they were not only the problem, but also the solution – the only solution.

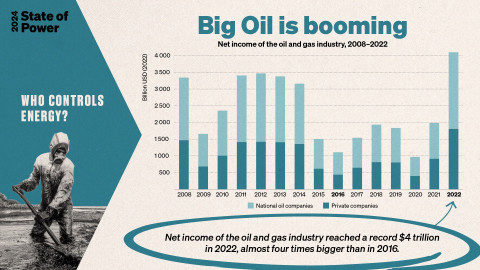

Finally, another important source of power is how fossil fuels are embedded in our industrial economies as a whole and in financial markets. That means a lot of other very rich and influential groups are heavily invested in their prosperity, or at least in not getting out of oil and gas too quickly. Oil and gas companies, for instance, represent a significant chunk of the market value of most major stock exchanges. There is no way that big financial players such as BlackRock will shift significantly away from fossil fuels, as it would also break their own business model.

Is Big Oil affected at all by today’s predominant climate policies? How are they responding?

Olivier: In the last decade, Western oil majors – especially the European ones, such as Total – have toned down their criticism of climate action, and they have sought to adopt an apparently more progressive attitude. They publicly recognise that climate change is a big issue and that we should do something about it. But what exactly should be done about it, and who should pay, are the key questions.

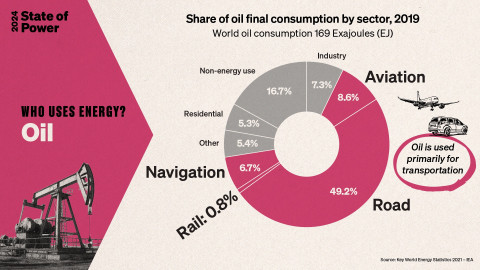

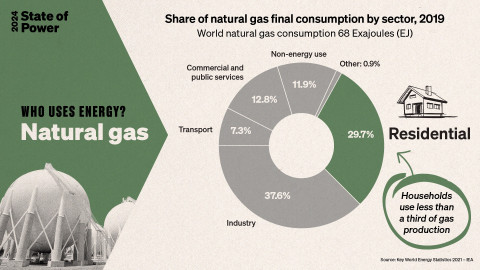

To put it simply, what we call ‘energy transition’ must have three components: developing clean, renewable energy, getting out of fossil fuels, and finally reducing our overall consumption of energy and materials in general. Basically, big oil companies like TotalEnergies want us to talk only about the first component, while adding a lot of technologies that have very little to do with renewable energy such as carbon capture and storage or agrofuels or even hydrogen into that ‘green’ basket. And they want governments to fork out a lot of money to pay for these, and they want to control the renewables sector. On phasing out fossil fuels, they want to talk about it as little as possible – as we have seen recently when only some very feeble language about a possible fossil fuel phaseout was added in the text of the UN climate summit’s Dubai accord. The executives of TotalEnergies, for instance, publicly accept there will be an end to fossil fuels at some point, but only in a distant future. And the third component, overall reduction of consumption, is barely mentioned at all.

What we have seen in practice these last few years is the exact implementation of this programme. There is no progress on fossil fuel phaseout, and only some on renewable energy development, but that is being added to the current energy mix instead of replacing fossil fuels. Sadly, many western governments have basically accepted the version of ‘climate action’ promoted by Big Oil and are putting their faith in big corporations to deliver the energy transition – which will inevitably always remain too little, too late, and come at a huge cost for governments, communities and customers, while the corporations and their shareholders will get all the profits and claim all the merit.

Is Big Oil seeking to block an energy transition or to shape it for its own benefit?

Clémence: For five decades, Total and its peers obscured the climate crisis, diverting attention from fossil fuels as the key driver of global warming. Along with Exxon and others, it has been well documented that they deliberately lied about the climate crisis – their knowledge of its causes and their responsibility for it. And the consequences are borne now by our communities: those succumbing to climate impacts today were effectively condemned in a boardroom 50 years ago.

As temperatures have soared in recent years, denying the reality has become futile. In response, Total is ramping up its communication game, rebranding itself as a ‘responsible energy major’, suggesting a significant shift in strategy. But their purported involvement in the energy transition, as well as by other Oil and Gas majors serves as a smoke screen, enabling them to profit from ongoing fossil fuel exploitation. And they're eager for us to keep buying into their deceptive tales.

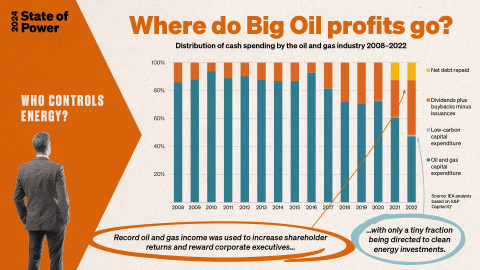

Despite its changing narrative, Total allocates almost all of its investments to extracting more carbon from the ground instead of embracing renewable energy. A whopping 75% of its 2022 investments are in oil and gas. By 2030, two-thirds of corporate investments will still be tethered to fossil fuels, impeding genuine progress.

Their defence? Blame the consumers – shifting responsibility to individuals rather than taking meaningful action. But they are the only ones, along with their shareholders, to benefit from this inaction. This is why given the rise of climate impacts, the slogan #makethempay has received so much traction.

What has the climate justice movement learnt – or should have learnt – from decades of challenging Big Oil?

Olivier: Basically, that you can't hope to tackle the climate crisis without tackling corporate power. Parts of the climate movement believed that they could change Big Oil from the outside, whether through engagement, campaigning, name-and-shaming, etc. But Big Oil doesn't want to change and has enough power and influence to avoid or delay change or deflect most of its effects on others. ‘System change’ won't come from them, as they are the system.

There have been very valuable and effective campaigns and actions, which all remain very necessary and very relevant, and on many occasions have achieved victories for the climate movement. Persuading investors to divest from fossil fuels or cultural institutions to give up Big Oil sponsorships is a big deal. So are climate lawsuits against corporations such as Shell, TotalEnergies or ExxonMobil. It has played a key role in undermining these corporations’ social ‘license to operate’. If we look at TotalEnergies, they have been forced to communicate almost exclusively about their investments in green energy and their climate commitments. But on the other hand, they are still there and still powerful and still fighting every communication and legal battle with all their resources. So, there’s always the risk that our victories remain too little, too partial, and could be reversed – indeed, we are currently in a moment of backlash against some of our previous gains. So, I would say what was missing is an attempt to tackle the power of Big Oil from the inside.

Clémence: The divestment movement is a strong example of a system change approach and achieved remarkable success in the last decade. It strategically bypassed calls for Big Oil to change and instead focused on eroding its pillars of support: its social license, funding access, and influence over government and institutions by asking them to cut their ties with the industry.

Grassroots mobilisation was the backbone of the movement, and we should always strive to organise diverse groups and initiate new local initiatives, tying social justice with climate justice.

As our movement grew, increased scrutiny prompted institutions to divest to avoid reputational risks tied to supporting these reckless industries. Then the targets became increasingly broad, leading to a big domino effect, compelling huge financial entities such as the European Investment Bank, or major cultural institutions such as the Tate or the Louvre to reconsider their traditional support. The divestment campaign, on a global scale, created a unified front against fossil fuel investments.

Legal and political advocacy to hold Big Oil accountable, and collaboration with other social justice movements, has also reinforced our strategic efforts, and, of course, first and foremost, supported frontline communities fighting projects on the ground. Our interconnectedness necessitates collective action and solidarity.

Looking ahead, we should stay focused on a long-term vision, recognising that systemic change requires persistence, adaptability and solidarity. Our evolving movement must continue to learn from setbacks and strive to maintain momentum. In a nutshell, this fight against Big Oil has taught us that the best way to resist them is to organise collectively through a diversity of tactics, but with a shared vision and understanding of how we make change happen.

And how have our movements evolved to challenge Big Oil? What are the big challenges ahead?

Clémence: We've transitioned from solely emphasising consumer responsibility to adopting a more holistic approach that considers both demand and supply dynamics.

Globally, we've notched up significant achievements. Billions have been divested from fossil fuels, major infrastructure projects have been halted, and commitments secured from local authorities and entire nations to transition away from fossil fuels. Our influence is also evident in the discussions on phasing out fossil fuels at UN climate talks, garnering support from over 130 states.

But there are global political trends that threaten progress. Activists are grappling with burnout, despair, and the challenge of recreating the momentum of the 2019 mobilisations. The years 2020 to 2023 have been a tumultuous period, marked by the impact of COVID-19, lockdowns, and a prevailing sense of powerlessness. The rise of the far-right puts the few progressive achievements at risk of a deep and severe backlash. The reality that each additional year we lose necessary action may lead to millions more lives lost is sobering. In that sense, slowing down the industry is an impressive achievement, but not enough.

Internal differences of opinion are another hurdle. Some advocate for a more aggressive, immediate approach, while others stress the need to expand and consolidate our base. While diversity within our ranks is a strength, it also poses challenges in terms of collaboration and coordination. Yet building unity is essential for setting the stage for reaching critical tipping points. We must recognise the gradual nature of our organising efforts and understand its significance in paving the way for larger transformative moments.

What are the main pathways today for undermining or overturning Big Oil’s power?

Olivier: It would be nice to think we can just ignore Big Oil and build a different energy system based on renewables, from scratch, independently of those corporations, and just let them slowly rot and disappear. The problem is that they are continuing to invest in new oil and gas production, they are actively undermining political action that would reduce the consumption of fossil fuels, and today they even manage to capture a large part of governments’ political support and funding for ‘clean’ energy. We have to disarm, muzzle, and render them unable to do any more harm. So yes, it’s necessary to start building a different system, but we cannot escape some form of direct confrontation with the power and influence of Big Oil.

Traditionally, many people in the climate movement and on the left assume that the best way to do this is through regulation – that governments should step up and force them to change, to exit fossil fuels while not raising prices and firing their workers. It might work in theory, but in practice this is not happening, because governments are unable and often unwilling to introduce effective regulations on such large corporations and to enforce them. Big Oil is already way too big for that. That doesn't mean we don’t need regulation, but we also need to reduce Big Oil's power in itself and put it under control. And the traditional way to do that is nationalisation.

One more thing about regulation: when it comes to tackling Big Oil, we don't need just one level of regulation, for instance regulating their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. We need a whole range of regulations to act on the different pieces and turbines of the machine – which we detail in our report, TotalEnergies - This is what a phaseout looks like. One very important aspect is the regulation of lobbying in the wider sense, including revolving doors and all forms of contacts between officials and industry representatives. If you don't regulate lobbying effectively, you will never be able to regulate anything at all effectively, because you’re at risk of corporate capture. If you have strong rules about lobbying and conflicts of interests – such as those that have been introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) for instance for tobacco – then you have a better chance to get effective regulation that is actually enforced. That is why proposals – such as those of the Fossil Free Politics coalition in Europe – to introduce the same kind of rules for fossil fuels as for tobacco are potentially a key part of the solution – but they need to be applied at all levels of influence, not just at the UN and its climate summits (Conference of Parties, COPs).

How could nationalisation be done given the economic and legal obstacles?

Olivier: The act of nationalisation is not a problem from a legal perspective. It can be done through a simple act of legislation. It has been done in the past, including recently, and even by right-wing, pro-market governments to bail out banks for instance. The question is how much it would cost, and whether it's ethically acceptable that the current shareholders of Big Oil – which are mostly institutional investors such as BlackRock, Vanguard and others – should be allowed to walk out with billions of euros and dollars that they have basically earned by investing in climate destruction.

If France, for instance, passed a law to nationalise TotalEnergies, they would have to fork out in theory about €150 billion to acquire all the company’s shares, plus potentially face compensation claims by some shareholders or partners that could argue they have been unduly deprived of potential profits. And that’s before taking into account all the costs of getting out of fossil fuel, decommissioning installations and setting up a post-fossil fuel energy company that serves the public.

€150bn is the official market value of TotalEnergies, but there are many reasons to argue this value is vastly overblown, because it is based on the assumption of exploiting all of the company’s current fossil fuel assets. This is because they are so-called ‘stranded assets’. So, in our report we propose to set up a commission to assess the fair value of TotalEnergies – which is usually done in the case of a nationalisation – but taking account of the specific and problematic nature of those assets. We also explore another more radical option: a requisition instead of a nationalisation. Again, it has been done in the past, but only in very specific circumstances, often linked to a state of war. The argument would be that because of its past abuses and its current sabotage of urgently needed climate action, a company such as TotalEnergies can be requisitioned by the government. This doesn’t mean there is no compensation, but there would no longer be a pretence that this is a ‘normal’ market transaction.

In any case, even €150bn is not too high a price to pay. Western governments have frequently shown in the past – after the 2008 financial crisis and more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic – that they were able to find tens of billions of dollars to bail out the corporate sector and financial markets.

What would effective and just nationalisation of Big Oil look like? How could we ensure it delivers a just energy transition given the poor record of current state-owned energy companies?

Olivier: Needless to say, state ownership is not a solution in itself. There are numerous state-owned companies around the world that are just as dangerous as private-owned corporations. A state-owned company can be even more influential on government policies and priorities, as we know very well in France with the case of EDF, our pro-nuclear, state-owned electricity corporation. For this reason, many people in the climate and environmental movement are very wary about nationalising TotalEnergies.

I would argue that some form of public takeover is necessary and unavoidable to wrest a corporation like Total away from the grip of financial markets. Only states have the resources and the capacity to conduct such a large political, financial and industrial operation. But it must be done as part of a wider democratic process from the very start, involving citizens, stakeholders and of course workers. We propose to begin with a citizens’ convention and to introduce the kind of inclusive, transparent and participatory governance that many state-owned enterprises lack today.

There are very good examples to draw inspiration from in the remunicipalisation movement, even if it is generally at a lower level of governance. Nationalisation must be first and foremost a democratisation of the company, both internally and in its relationship with the rest of society. For us, eventually, after TotalEnergies has been taken under public control and has divested from its fossil fuel business, it must be folded into a larger public energy service, or become a citizen-owned company, or a combination of both.

And we think there could also be an international dimension to the process – with different countries conducting the same process with their national oil and gas companies at the same time – Shell in the Netherlands/UK, ENI in Italy, etc. This would give the whole process much more traction, as well as allowing some form of mutualisation of costs. The reflections we have developed about the specific case of TotalEnergies in France are not isolated. There are other organisations and think tanks thinking about this process in various countries.

How do we ensure Big Renewables don’t follow the path of Big Oil?

Olivier: Currently, you could argue that Big Renewables are not only like Big Oil; they are the same corporate players. We participated in a recent report coordinated by the Transnational Institute, Green Multinationals Exposed, that makes exactly this point.

As the established energy giants invest more and more in renewable energy, their business is still based on the same model: profit-oriented, extractivist (in terms of minerals and land), detrimental to communities and workers, and neo-colonialist, as many of the large-scale solar or wind projects are in the global South or in remote regions to serve global North interests.

There is another potent strand that we need for the energy transition: one that is focused on reducing consumption rather than just adding capacity, on meeting the needs of people rather than of industries, and on building democratic, partly-decentralised energy systems. The latter version of transition is the only one that’s actually viable. The former is a dead end from a social and climate perspective.

Do you believe we can finally defeat these oil and gas giants like Total? Where should we next focus our efforts as climate activists?

Clémence: Beating giants like Total is a huge task. But to reignite the flame of systemic change, the movement must confront this sense of powerlessness head-on.

The recent rise in climate activism, seen for instance with Just Stop Oil, highlights the urge to take immediate action. And with the crisis multiplying scarily, it’s time to focus on changes that really matter to people. Shifting our strategy means owning the solutions and telling stories that highlight that a positive route is possible, which is even more important if we want to stand a chance to defeat the rise of extreme right-wing movements across the world. The focus must be on doing things right – helping communities without hurting them – while holding those in power accountable.

As we are nearly half-way through the crucial decade to tackle global warming, decisions by 2025 are make-or-break. A clear plan by 2025, aimed at the 1.5°C target, must point towards a future powered by renewable energy. Making renewable energy bigger means we need to keep addressing financial issues – we need about $1.5 trillion of investment yearly by 2030.

At 350.org, we're in this with our supporters, offering support and guidance. Together, we're building a foundation for energy democracy and a fair, just renewables revolution. Our community, built through effective campaigns and steady contributions, is a powerful force for a future free from fossil fuels.