State-Run Oil Companies and the Energy Transition The case of Colombia’s Ecopetrol

Topics

Regions

Colombia’s government is attempting through its state-owned oil company, Ecopetrol, to manage the decline of its oil extraction and to invest in transition to renewable energy. Its path to an energy transition is complex, but it has far more potential than a private-sector led model to be successful and equitable and it deserves international support.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

The pace and scope of the energy transition have been the subject of much-heated debate within the new Colombian government and public discourse. Shortly after the inauguration in August 2022, other officials announced the intention to radically and rapidly transform the hydrocarbon sector. The-then Minister of Mines and Energy, Irene Vélez Torres, an academic with roots in the environmental movement, affirmed at the WEF that Colombia would swiftly shift away from fossil fuels: ‘We have decided not to award new oil and gas exploration contracts, and while that has been very controversial, it’s a clear sign of our commitment in the fight against climate change’.

By March 2003, the then-chief executive of Ecopetrol, the state-controlled oil company, warned that changes would have to be measured and gradual to achieve the energy transition. ‘There is no substitution in which you can just flip a switch to turn one thing off and another on’, Felipe Bayón told the Financial Times. He added that ‘it will take a lot of time, effort and money to ensure that other industries take its place’. In the same vein, he had also said in Davos that Ecopetrol had a gradualist, 20-year strategy: ‘The country will need the hydrocarbon exploitation that the company carries out. Ecopetrol could represent 10 per cent of Colombia’s budget, and we still need the dividends, royalties and taxes it generates’.

The pledge to halt oil and gas projects had been included in Petro and Márquez’s election campaign, but not every cabinet member was happy with such a commitment. José Antonio Ocampo – the progressive government’s first finance minister, an internationally renowned economist and former Executive Secretary of the United Nations Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLA-CEPAL) – had warned that Petro’s administration would analyse the 180 existing contracts before deciding what to do next. ‘Any energy transition that reduced exports would have to be gradual and prioritise gas self-sufficiency’, Ocampo declared to the Financial Times.

This chapter focuses on Colombia as a relevant case study for a broader research agenda. It addresses the role of the state in the energy transition vis-à-vis the global economic and financial system, as well as the significance of national oil and gas companies (NOCs or NOGCs) in current debates about energy sovereignty in the context of climate change. The first section analyses the current significance of hydrocarbon production and the prospects of state-run companies in Latin America and globally. The chapter then moves on to analyse issues and tensions that shape discussions about the transformation of Ecopetrol, culminating in a synthesis of ongoing political and policy discussions in Colombia that could be significant for future research and campaigns in other countries of Latin America and elsewhere.

The relevance and transformation of state-run oil companies

In the months leading up to the COP 2022, the political and business weekly, The Economist, published an article titled: ‘State-run oil giants will make or break the energy transition’. Together, NOGCs hold 66 per cent of the world’s oil and 58 per cent of gas, and provide around 40 per cent of the capital invested in these sectors. The title alluded to the poor decarbonisation record of state-run companies. Nevertheless, The Economist recognised that Ecopetrol bucked the trend and that the Colombian company ‘is involved in wind and solar projects and recently acquired an electricity-transmission company’.

The resilience and immense economic and political power of the oil and gas industry’ have been the focus of many recent journalistic and academic publications. An article in Nature shows how climate spending lags while the nine largest oil companies in 2022 totalled $457 billion in profits, equivalent to a sixth of the annual investment needed to meet government climate pledges. Three of these nine companies are state-owned or state-controlled (Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, Norway’s Equinor, and China’s PetroChina), and six are owned mainly by private shareholders (ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, TotalEnergies and ConocoPhillips).

Ecopetrol and other public enterprises operate in a regional context in which hydrocarbon production is undergoing strong and rapid transformations. According to recent appraisals, oil and gas extraction in Latin America and the Caribbean has experienced “tectonic” and “likely irreversible” changes during the past decade. Production fell from 10.4 million barrels of oil per day (md/d) in 2010 to 7.8 million mb/d in 2022; the region’s share of the global market dropped from 12% to 9% in the same period; and the two traditional hydrocarbon-exporting countries, Mexico and Venezuela, show signs of decline in their oil industries. Brazil has repositioned itself as the world’s eighth-largest oil producer. Small and sparsely populated Guyana currently challenges the supremacy of traditional producers in the region and has become one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador face stagnant or decreasing oil outputs.

As will be discussed in more detail below, the state’s majority ownership of Ecopetrol’s shares is an essential factor in the prospects for the transformation of the Colombian company. In the region, the spectre of privatisation of the energy and oil industry had resurfaced when the ultra-right libertarian Javier Milei, the recently elected president of Argentina, had proposed the privatisation of 41 public enterprises, including nuclear energy plants, the energy infrastructure agency, and YPF, the national oil company. In January 2024, facing strong social and political opposition, Milei was forced to backtrack on his oil and gas privatisation plans.

Regardless of their ownership structure, oil and gas companies are crucial determinants of global emissions and access to energy. Private companies, however, are much less accountable than NOGCs and far more challenging to transform. Private transnational corporations (TNCs) active in the oil and gas sector have been propped up by a complex system of national and international government subsidies that ensure the privatisation of benefits of oil and gas production while socialising its economic, environmental, and social costs. As two scholar-activists have argued:

Public ownership, by itself, does not guarantee that we will fully replace oil and gas with renewable energy in time to avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis (...). But we do not advocate public ownership because it is a magic bullet – we advocate it because it is our only shot. The profit math is just as clear as the climate math: corporations exist to generate profit and enrich shareholders, both of which require them to produce their product. No amount of shareholder activism can possibly do better than slowing or attenuating the rate at which corporations pursue this basic mandate. ‘Market-based solutions’, in this case, are a contradiction in terms: the market is the problem.

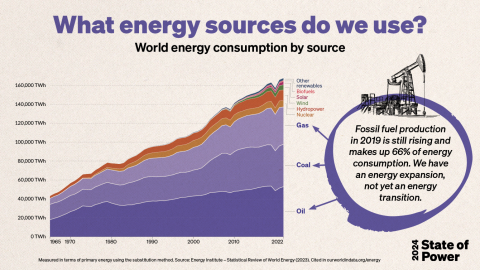

The same analysts contend that public ownership would make it possible ‘to decommission a recalcitrant industry in time to stave off climate disaster’, and offer ‘an opportunity to build something better in its place’. From a similar perspective and challenging the claim that NOGCs by their nature hinder the just energy transition, a growing number of trade unions, environmental organisations and research centres point to the pursuit of endless growth and capitalist accumulation as the root cause behind the global trend of energy expansion, not a transition. Instead, the alternative public pathway approach identifies state-owned or state-controlled companies as strategic players in limiting climate change and avoiding its worst impacts.

The reinvention of Ecopetrol as an energy company

In the 1920s, the US-based Tropical Oil Company (Troco) obtained the right to exploit oil in Colombia after taking control of the infamous Concesión de Mares. The private company dominated oil production in the exploration, production, refining, transport, domestic distribution and export of oil in the country during the first half of the twentieth century. Following decades of political debates and militant trade union struggles demanding nationalisation of the hydrocarbon sector, the reversion of the Concesión de Mares to the Colombian state led to the founding of the Empresa Colombiana de Petróleos, Ecopetrol.

In 1961, Ecopetrol acquired the Barrancabermeja refinery and, 13 years later, bought the Cartagena refinery (today, the country’s largest and second-largest refineries, respectively). In 1970, Ecopetrol adopted its first organic statute, which ratified its nature as a wholly state-owned company linked to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. From September 1983, Ecopetrol increased the scale of its oil production following the discovery of the Caño Limón field, a deposit with reserves estimated at 1.1 billion barrels. In 1986, Colombia became an oil-exporting country again, and extended its oil self-sufficiency in the 1990s following the discovery of the Cusiana and Cupiagua fields.

Oil production in Colombia peaked in 2014 at 1,040 thousand barrels per day (kb/d), and for the past ten years has been falling despite promising new offshore discoveries, which would take a long time to develop. Despite the fall in production, oil, gas, and mining account for over half of the country’s exports. Ecopetrol is Latin America’s fourth-largest oil company and Colombia’s main exporter. It represents around 30% of the country’s exports and provides a vital source of foreign currency earnings in an economy affected by constant fiscal and current account deficits. The company’s investment plans for 2024 range between $5.7 billion and $6.7 billion, increasing production up to 730 kb/d and operating 360 development wells and 15 exploratory ones.

The significance of Ecopetrol in the Colombian economy

The full significance of Ecopetrol and Colombia’s overall profile as a country dependent on extractivism is evident from the export data. More than half of the country’s foreign sales are in the hands of 16 companies, most of which operate in the hydrocarbon and mining sectors. The top 10 are headed by Ecopetrol, followed by mining companies Drummond (coal) and Carbones del Cerrejón (coal). Six of the remaining seven companies operate in extractive industries: Cerrejón Zona Norte (coal), Trafigura Petroleum (oil), Frontera Energy (oil), Reficar (petrochemicals), Cerro Matoso (nickel) and Terpel (petrochemicals). Despite Colombia’s reputation as a coffee-growing country, the National Coffee Growers Federation occupies eighth place.

Ecopetrol accounts for approximately 65% of the country’s oil and 80% of its gas production; 60% of oil barrels extracted are produced by the state-owned company, and the Reficar and Barrancabermeja refineries are supplied by the Colombian NOGC. Considering its importance in the national economy – around 100,000 jobs depend on Ecopetrol, and that the company accounts for more than 6% of the GDP – the main oil workers’ union has expressed concerns about the long-term prospects of the industry if oil and gas production fall:

Maintaining the oil and gas production to guarantee the supply to refineries to provide diesel and gasoline for the national market is imperative. Significantly reducing investments in production and exploration would jeopardise Ecopetrol’s continuity in the future, increase the risk of shortages and undermine national energy security. The country currently has 7.1 years of oil reserves and 7.5 years of gas reserves. Therefore, any reduction in investments to sustain production would shorten this window of time.

A shift away from oil?

The apparent contradictions in the discourse of Colombian government officials, Ecopetrol executives, and trade unionists regarding the speed and ambition of decarbonisation reflect the complexity of the proposed transition. Colombian trade unions have a long tradition of internal debate, and the current coalition government comprises diverse political parties, which need some time to arrive at a relatively coherent position. Nevertheless, progressive Colombian forces seem to agree on how to move beyond fossil fuels, which can be summarised in the following five points: (1) current exploration contracts will be upheld; (2) exploitation of proven deposits will continue; (3) no new exploration contracts will be awarded; (4) Ecopetrol will diversify its portfolio to include low-emission technologies and renewable energy sources. And most recently (5) Colombia might need imports from neighbouring Venezuela to ensure energy sufficiency during the transition.

The government’s plans to transform Ecopetrol into a company that moves beyond hydrocarbon extraction have raised concerns among oil workers. The Union Sindical Obrera (USO) has a rich and dynamic internal culture of political debate across its diverse ideological currents, varying in positions and approaches to the just energy transition. USO’s members overwhelmingly voted for Petro and Francia and organised to secure their victory. Despite that background, union members have expressed concern about the pace of the proposed transition and the cancellation of new exploration contracts, arguing it puts Ecopetrol at risk of disinvestment and exposes the country to energy dependence. In a statement issued in October 2023, the union commented on the Ecopetrol’s proposed cuts:

Recent decisions by Ecopetrol’s managers to curb the investment budget […] put at risk the continuity of its core business. This decision also has a strong impact on public finances because Ecopetrol contributes an average of $20 billion annually to the financing of the state between dividends, taxes and royalties paid to the nation (…). Thus, in 2026 we will be producing 472,000 barrels per day, which will only allow us to maintain supply to the two refineries, and we will get no income from exports. The reduction of Ecopetrol’s investments will result in the contraction of the oil sector in general, given that other companies in the sector rely on Ecopetrol’s investments as their main source of income, and if Ecopetrol’s budget declines, investment in the sector will fall across the board causing a domino effect.

In response to union concerns and criticism from political and business circles, Ecopetrol’s current president, Ricardo Roa, has reiterated that the company’s future will not be affected by the energy transition plans announced by the government. ‘We’ve never said that we’re going to wind up our traditional business’, Roa said at a recent business forum. ‘The oil and gas industry in the country is not going to end’, he added, explaining how investing funds derived from fossil fuels extraction would be key to financing the transition to renewable energy. The current Minister of Mines and Energy, Andrés Camacho, gave a similar answer in an interview with a Spanish newspaper in which he was asked if the ministry would approve more contracts for oil and coal exploration:

We have a policy of developing energy exploration as part of the energy transition. That does not mean that we will not do more, but rather that we are taking steps toward new contracts for exploiting geothermal energy, white hydrogen and other types of energy. We are going to develop new contracts for the energy transition. Since the day I arrived, I’ve said that the transition is being done with hydrocarbons. We will need them for a time, even up to 2040, 2050... If there are no substitutes for the petrochemical industry, we will continue to require hydrocarbons. The idea is that our dependence on them will decrease.

The Challenge of diversifying Ecopetrol

Two years before Petro and Francia took office, Ecopetrol had already publicised a plan for decarbonisation to reach net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, including concrete steps to diversify away from oil and gas. The clock is ticking: Colombia has a horizon of 7.5 years of hydrocarbon supply. If Ecopetrol or other companies active in the country do not develop a significant new field before then, the country will have to import all the oil it needs. Energy supply and demand projections for 2050 indicate that Colombia will continue to require gas, gasoline and diesel, so if Ecopetrol is unable to meet the demands of the domestic market, it will be necessary to import from the Gulf or other parts of the world that continue to extract fossil fuels.

More than 40% of the expenditures that Ecopetrol has planned for 2024 focus on the energy transition. The company’s business plans highlight the objective of diversifying activities into the broader energy sector, with expansion into areas beyond hydrocarbons. Planned capital expenditures (CAPEX), a good indicator of the real commitment to diversification, includes concrete investments in ISA, a Colombian company active in electricity transmission, roads and telecommunications throughout Latin America that Ecopetrol acquired in August 2021, paying $3.58 billion for 51.4% of the shares. According to business analysts:

The decision to buy the state’s stake in ISA took place at a time when Ecopetrol’s official strategic plans did not include CAPEX for diversification outside oil and gas production. The purchase was a response to specific market opportunities outside oil and gas, where potential new business opportunities are assessed on a case-by-case basis. Still, with this move, Ecopetrol has shown strong leadership among Latin American NOGCs with regard to strategies to diversify its core activities.

Ecopetrol’s expanded role within the power sector would be crucial since even with the realisation of the more ambitious plans for the decarbonisation of energy generation the country will probably continue to rely on fossil fuels to meet electricity demand for decades. A Javeriana University academic argues that:

For Colombia to achieve full electrification and meet the goals of a just energy transition, we must have an installed capacity of 120 gigawatts. The country is currently reaching barely 20 gigawatts of installed capacity. That is why the strategy to significantly reduce the participation of fossil fuels in the energy mix cannot be done from one moment to the next. Fossil fuels must leverage this transition.

A recent study on transition challenges in Colombia reports that the total electricity demand in 2021 was 67 Twh (terawatt-hour). If all fossil fuels were replaced by electricity in 2036, electricity consumption would increase by another 160 TWh. In a scenario where the transport sector is supplied exclusively by biofuels, electricity demand would be 73 TWh lower, but biofuel production on that scale is highly unrealistic – and has potentially negative social and environmental costs.

The Colombian government has publicised a Hoja de Ruta de la Transición Energética Justa (Roadmap for a Just Energy Transition). This document systematises a nationwide citizen consultation process in which it was agreed that the transformation of the Colombian energy system should be based on four principles: equity; graduality, sovereignty and reliability; binding social participation; and a knowledge-intensive transition. In February 2022, Ecopetrol presented its strategic vision for 2040 and its operational and financial goals for 2022–2024. The long-term plan, Strategy 2040: Energy that Transforms, aimed at responding ‘comprehensively to the current environmental, social and governance challenges’. A year and a half later, the company updated that plan and proclaimed its goal to become ‘the leader in the Americas in the diversification of energy’, investing in ‘hydrocarbons, low-carbon solutions, power transmission, roads and telecoms’. It also reiterated its will to contribute to a ‘Just Energy Transition’ and its ‘commitment to energy security, the environment and social development’.

In November 2022, Ecopetrol confirmed the suspension of its fracking projects and the cancellation of the agreements with Exxon Mobil. Following years of highly contested internal debates, USO members reached an agreement in a 2019 National Delegates Assembly vote (77 in favour, five against, 22 abstained) to reject the use of fracking and to demand that the government speed up the transition of Ecopetrol to become an energy company focused on renewables. The suspension of fracking had been a campaign promise of the left-wing coalition Pacto Histórico (Historic Pact) and a leading demand raised by social and environmental activists during the paro nacional (national strike) – the series of protests that rocked Colombia in the first half of 2021, including massive street mobilisations against police violence, corruption, and cuts in health care and public services proposed by the government of right-wing President Iván Duque.

In the context of its Strategy 2040, the company has an ambitious plan to produce ‘green’ hydrogen, ‘green’ ammonia, and ‘methanol’, expected to bring between $20 billion and $25 billion in profits through 2040. In September 2023, Ecopetrol’s chief executive announced: ‘Between now and 2030, we must have incorporated nearly 1,900 megawatts in non-conventional renewable energy sources and by 2050 between three and five new gigawatts of renewable energy. That is Ecopetrol’s goal and aspiration in the energy transition’.

However, for Ecopetrol to expand into the power sector, it will be necessary to change the the legal framework. The Plan Nacional de Desarrollo (National Development Plan) 2022–2025 passed at the beginning of the current administration laid the groundwork for Ecopetrol to become an integrated energy company by repealing key articles in former legislation that that forced unbundling and prevented the functioning of vertically integrated energy companies.

The challenges of democratisation

The reference to Ecopetrol as a state-run and not state-owned company in the title of this chapter is not accidental. Over a 40-year period, various governments have attempted to privatise, corporatise and weaken Ecopetrol and other public enterprises, to the detriment of economic and social development and national sovereignty. The policies of plunder became more intense since the 1990s, including several waves of economic liberalisation that aggravated social inequalities and the continuation of the armed conflict, but workers’ struggles prevented the privatisation of Ecopetrol.

Since the mid-1960s, Colombia has gone through a so-called ‘low-intensity asymmetric war’ in which the country’s armed forces, left-wing guerrillas, far-right paramilitary groups and crime syndicates were directly involved, with the engagement of the US government and large Colombian companies and TNCs more or less covertly. In such a context, the distancing of Ecopetrol’s policies from the social needs of the working classes led to the company’s militarisation, as its control was contested between different sectors of Colombia’s ruling class. Links between the company and far-right paramilitary activities – including the assassination of trade unionists and local activists – have been reported in various parts of Colombia, in particular in the municipality of Barrancabermeja in the department of Santander, home to the largest refinery and Colombia’s main petrochemical centre.

Intra-class disputes over control of Ecopetrol led to a series of ownership and management changes over the last 30 years. Before 2000, Ecopetrol was an empresa industrial y comercial del Estado (an ‘industrial and commercial state-owned company’). In June 2003, Uribe’s right-wing government decided to make it a public shareholding company, until 2007, when it was converted into an empresa de economía mixta (mixed economy company), becoming Grupo Empresarial Ecopetrol. The modification of the company’s ownership and management structure also meant a regulatory change: Ecopetrol ceased to exercise its functions as a state agency administering the oil sector, a role transferred to the newly created National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH). Moreover, these changes meant that Ecopetrol went from being a public enterprise fully owned and managed by the state to a highly corporatised state-controlled company. In January 2023, a Colombian economist characterised Ecopetrol’s corporatisation as follows:

Ecopetrol is de facto privatised, even though the state has not sold its majority shares. This is the best form of privatisation for the private sector. Private persons are appointed as board members, private actors manage the state enterprise without contributing a single peso and administer it according to their own criteria and interests. Following the corporate governance rules of the OECD, an ultra-liberal institution of which Colombia is a member, the company is in practice managed not by the state but by private actors.

For some years, one recurring discussion has centred on reforming the company’s statutes. The Colombian state controls 88% of the company’s shares and thus has the power to submit a list of candidates for the nine-member board of directors through the Ministry of Finance. Since Ecopetrol is listed on the New York Stock Exchange, such appointments must be compatible with the strict criteria established by the Security Exchange Commission (SEC). One option that Petro’s administration explored shortly after taking office, which was criticised in political and business circles, was the possibility of adding a seat for a trade union representative. Having an active USO member on the Board of Directors has long been the union’s demand. The union’ president Cesar Loza told the Madrid daily El País at the end of 2023: ‘The majority shareholder [the Colombian state] has already called an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting to make some changes to the composition of the board of Ecopetrol. The proposal includes greater participation of women and, most likely, the integration of comrade Edwin Palma, vice-minister of labour [and a trade unionist and former president of USO] to the board’. While Palma’s addition would be welcome, USO members we interviewed underscored that Palma is a current government official and would not satisfy the union’s demand to include an active trade union member on the board of directors.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Conclusion

Colombia’s energy transition has several unique characteristics. The country’s president is a former guerrilla and an environmentalist very much grounded in the science of climate change, who points to the limitations of capitalism to meet climate targets. The national oil company has started to implement a radical transformation in its operations and founding mission, with one foot in the NYSE and another firmly placed on the road to a just transition. Trade unions and environmental organisations are eager to have a greater say on the transition, with proposals and demands that converge in some respects and diverge in others.

Like most other NOGCs, Ecopetrol faces enormous challenges, considering its crucial role in providing vital resources that the government needs to finance public services and a just transition, achieve energy security and sustain or generate hundreds of thousands of jobs. The commitment to transform and diversify operations to enable Ecopetrol to become an integrated energy company is unprecedented in the world. However, the adjective ‘just’ that precedes the characterisation of the transition announced in the company’s Strategy 2040 is not entirely precise in its scope and contents. The pledge is mainly reflected in the announced plans to expand access to energy services as a priority of the subsidiary company ISA. The official documents do not specify exactly how the transformation of Ecopetrol will be integrated into the framework of the Just Transition Roadmap launched by the Ministry of Mines and Energy, especially concerning the distribution of the benefits and costs of the energy transition and the impacts on workers and local communities.

From outside Colombia, the route Ecopetrol should take seems obvious and easy to follow: accelerate its transition away from fossil fuels, diversify and benefit ‘from improved resilience and reduced vulnerability to external and domestic pressures, such as oil and gas price volatility, supply disruptions, environmental disasters and investor pressure’. However, our interviews with representatives of government bodies, trade unions, environmental organisations and research centres in Colombia show that in fact the road is much bumpier, narrower and uphill than it might seem, for several reasons.

- NOGCs are crucial in the energy transition because they are some of the world’s largest oil producers and are often the largest companies at the national level. Researchers, trade unionists and environmental organisations need to deepen and expand their exchanges on the role of the state and the meaning and prospects of the public pathway in the energy sector.

- Colombia has very few remaining years of energy sufficiency, and depends on fossil fuels for its exports and public budget. This is one of the leading challenges facing the country’s decarbonisation ambitions. Current capacity for electrification is nowhere near meeting future needs. The energy transition requires political will along with financial resources. Colombia has proven capacity to generate solar, wind, marine and geothermal energy, but without resources the energy transition is not viable. The approximately $8 billion that Ecopetrol contributes each year to the state coffers cannot be ignored.

- Despite tensions and contradictory official discourse on the current direction of the energy transition, significant progress has been achieved, including the commitment to halt new oil and gas exploration contracts, the beginning of diversification of Ecopetrol’s portfolio, the decision to end fracking, and growing debates on the democratisation of Ecopetrol’s board of directors.

- Further democratisation will imply dealing with the legacy of the Colombian armed conflict and previous links between the far right and Ecopetrol and authoritarian repression, which disproportionately targeted oil workers.

The Colombian experience demonstrate how a just energy transition at the national level can be implemented only if there is a articulation between national plans and global strategies. For countries across the global South, the decarbonisation of the energy system is a monumental challenge. At the Latin American scale, it is feasible to transform the energy mix if there is political will that relies on strong state-owned energy companies as drivers of the transition, as the Uruguayan case has proven after a rapid and massive shift towards renewable generation in the previous decade. It would also be possible to conceive plans to export other types of fuels – e.g. green hydrogen, as proposed by Ecopetrol – but only if the potential renewable sources and the demand for them are sufficiently large. In any case, the restructuring of the oil industry is very complex and depends on a substantial transformation of international trade and financial structures and relations. The president of Colombia proposed in Davos to exchange foreign debt for a commitment to leave oil in the ground. In this respect, it is worth recalling that a similar proposal made by a neighbouring country, Ecuador, during the government of Rafael Correa did not meet with the expected response from the ‘international community’ and was used to justify a controversial expansion of oil exploration.

Hydrocarbons have long shaped Colombia’s economic, political and social structures and spurred its economic growth over the last decade, accounting for around half of its export earnings. In this context, Gustavo Petro has repositioned climate justice at the centre of his political agenda, alongside the fight against poverty and inequality. Whatever the resolution of current debates about the future of fossil fuels in Colombia, it will have a profoundly impact on Ecopetrol’s raison d’être and the country’s identity.

It is unthinkable to think of a transformation of oil extraction or a diversification of Ecopetrol and other NOGCs around the world unless their workers assume a substantial role in the transition, based on experiences and knowledge developed over more than a century. In this context, USO workers have explicitly stated their aspiration for Ecopetrol to lead the transition beyond fossil fuels. They have reaffirmed their interest in retraining and using the skills they matured on offshore platforms to build and operate renewable energy plants. But they also warn that the government’s plans must avoid a supply crisis and ensure the flow of revenues that the country cannot reject overnight, especially when it is already clear that oil and gas reserves will be exhausted in less than a decade.

The government led by Gustavo Petro and Francia Márquez is trying to show the world that it is possible to manage the decline and restructuring of oil companies for social benefit. Colombia has proposed the deployment of a global ‘Marshall Plan’ to fight climate change and has indicated that a tax on financial transactions could be a way to obstain some of the resources that are urgently needed. Debt swaps of forgiveness – as proposed by Petros in Davos, advised earlier by the Pacto Ecosocial Del Sur, and discussed at the two most recent COPs after the Prime Minister of Barbados presented the Bridgetown Initiative for a restructuring of the global financial architecture – could help oil-dependent countries to develop less destructive energy sources and continue to fund social policies and programmes. In this context, there is an urgent need to broaden and deepen the discussion on how to reclaim and transform Ecopetrol and other NOGCs in different regions of the world.