Socialising energy Lesson from radical housing campaigns in Germany

Topics

Regions

To regain lost momentum for an energy transition, climate and energy justice campaigners can learn from Berliners’ victorious referendum in support of a radical expropriation housing in 2021. This not only followed a strategy that put the costs on the corporations rather than people, it also goes beyond traditional public ownership to explore models of popular participation.

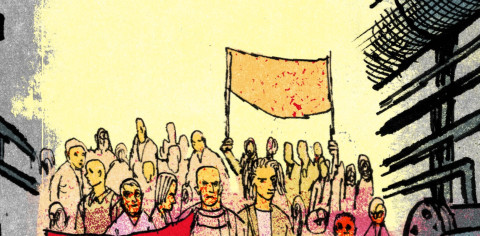

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Socialisation, re-municipalisation and the Berlin expropriation movement

Resistance to privatisation is as old as neoliberalism itself. While numerous successful re-municipalisations and defensive battles have managed to slow down the neoliberal onslaught on public ownership in Germany, the Left continues to find itself on the back foot.4 However, 26 September 2021 marked a significant turning point when the trajectory of battles against the detrimental effects of private ownership began to shift. The ‘Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co.’ campaign triumphed in a referendum in the city-state of Berlin, advocating for the expropriation of all private housing corporations owning more than 3,000 flats within the city. Much to the surprise of many observers and participants, a decisive majority of 59.1% of voters supported the resolution proposed by the initiative, which had been spearheading an impressive campaign for three years. This campaign galvanised several thousand Berliners, transforming them into activists committed to dismantling the stranglehold of colossal, financialised corporations on Berlin’s housing market.

The activists met with resounding success and have since tirelessly campaigned to ensure the will of the Berliners is upheld and the referendum is executed. Their struggle persists, as representatives of the real estate and construction sectors are well coordinated. Despite the poor reputation of private real estate among Berlin tenants, it is regarded as an acceptable partner by Berlin’s governing Social Democratic Party (SPD). The SPD’s aversion to expropriation is so strong that following its re-election in 2023, they opted to form a coalition with the conservatives rather than continuing the progressive alliance with the Greens and, notably, the Left (which support socialisation). The movement remains steadfast in its fight for the implementation of the referendum result, through tenant organisations, demonstrations, and other means.

The Berlin initiative has its legal basis in an article of the German constitution that has remained unused in the 70-year history of the (West-) German state. Article 15 of the German basic law offers the possibility of socialising land, means of production or natural resources irrespective of the will of private owners. While it makes clear that the current owners must be compensated, expert opinion is virtually unanimous that compensation can be below market value. Interestingly it specifies that socialisation means not just the expropriation of assets but also their transfer into the common economy (Gemeinwirtschaft). This is generally understood as involving the democratisation of decision-making and orientation towards public welfare rather than private profit.

The campaign built on the growing consensus in German society that neoliberal policies went too far. Following the privatisation drives in Germany from the era of Chancellor Helmut Kohl in the 1980s and 1990s, extending well into the 2000s, a potent countermovement for re-municipalisation has been brewing in Germany for the past 20 years. Between 2005 and 2017, the energy sector alone witnessed 284 re-municipalisations of public infrastructure that had previously been privatised.5 This surge was propelled by local citizens’ movements. In 2013, a citizens’ referendum compelled the city of Hamburg to repurchase all municipal network infrastructure (including water, energy and heating). Rural municipalities re-acquired privatised grids and formed supra-regional municipal associations, and some previously state-owned housing was repurchased in Berlin and other locations. The trend towards re-municipalisation is a promising sign for the revival of public ownership of public services and for the socio-ecological transformation. However, the momentum has faltered in recent years, suggesting that the peak of the re-municipalisation wave may have already passed.6

The expropriation struggle in Berlin is based on a very similar political starting point, but goes far beyond re-municipalisation projects. Berlin was hit by a massive wave of privatisation in the 2000s. After a banking scandal involving a state-owned bank, Berlin found itself on the brink of bankruptcy, prompting the local government to enforce a stringent austerity programme. Hundreds of thousands of formerly municipal flats and plots of land were sold at an embarrassingly low price to hedge funds, private companies or pension funds. Following numerous mergers, acquisitions, and overall market consolidation, these flats now belong to a handful of large Europe-wide groups such as Vonovia, Heimstaden, or Adler. In the early 1990s, over 500,000 flats in Berlin were state-owned – by the end of the 2000s, only 250,000 remained.7

Berliners are acutely aware that these corporations do little with these flats beyond exploiting them for profit through escalating rents and speculative valuations. Consequently, Berlin is now in the midst of a housing crisis. The city has a high influx of people and a strong demand for housing, a situation that private corporations are exploiting by raising rents exorbitantly and constructing expensive new flats rather than affordable social housing. As the campaign activist Isabella Rogner stated in a 2023 summer hearing in the Berlin parliament: ‘When I assess the past two years, my primary observation is that the situation on the Berlin housing market is worse than ever for us tenants. If this trend continues, we will have lost the city that you the Berlin government all claim to defend in a few years. You have the opportunity to save this Berlin, to preserve the homes of millions of people and to shield them from displacement. The instrument for this, socialization, is right before you’.8

The expropriation campaign focuses precisely on the obvious failure of the privatisation of housing. Instead of seeking to re-municipalise these flats by buying them back at overheated market rates and hoping that the private owners will be willing to sell, the campaign has taken a big further step. It proposes to expropriate big housing corporations at well below market value and – interestingly – to not return them into state control. The campaign has presented a concept for the administration of the flats to be expropriated, in which the tenants, as well as representatives of civil society, make decisions in council structures, with the state playing only a minor role. Critically reflecting the experiences of state ownership in the 20th century, the initiative presents an imaginative model centred around the radical democratisation of decision-making.9

Socialisation as the campaign proposed went far beyond classical models of ownership: expropriation of large companies, compensation below market value and radical democratisation and de-marketisation. These ambitious demands were the campaign’s starting point – and they triumphed. The initiative presented a concept that proved convincing: Berliners have long had good experiences with communal housing or municipal water supply. While far from perfect, there were political and organisational experiences with public ownership of these public service sectors. Coupled with a political programme that adequately tackled the scale of Berlin’s housing crisis, there were broad majorities in favour for expropriation. As recently as 2018, when the campaign was launched, such an outcome seemed unthinkable.

In Germany, there is awareness of various forms of state ownership in basic services, even under capitalism: municipal water companies, state schools and municipal housing are part of people’s lived experience. However, public ownership is rarely fully democratic and seldom completely rejects the profit motive in favour of focusing on public goals. States or municipalities are just as capable as private owners of pushing for the extraction of profits and underinvestment in critical infrastructure. This is especially true if assets have to be bought back at market rates, thereby constraining the possibilities of public actors. Moreover, state property is always at risk of being privatised once more when budgets are tight. Despite some good experiences with re-municipalisation, which have led to improved quality of supply and cheaper prices, there is no discernible trend towards a wave of public ownership appropriate to the problems of the 21st century – especially not in the energy sector.

The German energy sector and the role of local, small-scale ownership

Re-municipalisation or the establishment of new municipal or cooperative companies alone will not be enough to manage the energy transition quickly and in a socially just manner. There is a need to socialise large corporations to break their market power, direct massive investments into renewable energy generation at scale and to transform the sector overall, together with workers, who have both the organising power and the knowledge necessary for the transition. Much depends on not having to buy back assets at market value and properly democratising energy companies – and this will be possible only within the framework of socialisation.

The current ownership structures and marketisation in the German energy system are a product of the Europe-wide liberalisation of energy systems that have been pushed through since the 1990s in the context of the creation of a single EU internal energy market. In essence, the EU energy deregulation packages since 1996 have fostered a system in which private corporations have been able to seize significant segments of the energy sector, and energy, once considered a ‘natural monopoly’, has been transformed into a tradable commodity.

Current ownership structures in the German energy system have also been shaped by laws that were negotiated by the Green minority in government in the early 2000s. The promotion of renewable energies has been regulated since 2000 by the Renewable Energy Act, which was basically a mechanism for incentivising the construction of renewable energies through a consumer-paid feed-in tariff.10 This subsidy mechanism with a guaranteed purchase of green electricity created a secure market environment for private, small-scale investments and was extremely successful as a model for this period. In retrospect, however, this subsidy mechanism helped initiate an expanding de-risking model of green transformation, which has been observed ever more intensively in recent years.11

The German energy transition was largely driven by small private actors: energy cooperatives, private individuals with solar panels on their roof, municipal utilities or medium-sized energy companies that invest solely in renewables. The feed-in tariff gave small market players a regulatory framework and economic security that has long secured investments in renewable energies and even led to the German solar industry to be the world market leader for a short time.

From the 2000s, the German ‘Energiewende’ (energy transition) was a decentralised energy transformation project featuring a diverse range of actors and was consequently lauded and replicated internationally. While small-scale, private ownership clearly often benefits middle-class consumers and does not necessarily support workers and poorer, urban populations, at least there was proper investment in renewables. Up until 2019 cooperatives, individuals and farmers held a share of 40.4% of renewable energy in Germany.12 This is currently shifting however: the proportion of small-scale citizen energy (Bürgerenergie) is slowly but surely declining. Project developers, banks, investment firms, and the four major energy corporations that dominated the fossil market are swiftly moving into renewables. Their share is expected to continue increasing in the years to come, with local, cooperatively owned, and small-scale energy producers set to continue losing their share.13

Socialisation for democratic public ownership at scale

Local, small-scale ownership and re-municipalisation must play a role in the energy transition. However, it is evident that a socially and ecologically just energy transition must in addition focus on building large-scale public and democratic models with the long-term aim of a complete decommodification of the sector and provision as a universal public service.

Socialisation as proposed by the Berlin initiative means the large-scale expropriation of privately owned assets and their transfer into democratically governed and publicly owned institutions centred around public goals. Socialisation has demonstrated its viability as a movement strategy, particularly because it politicises the antagonism between large privately owned corporations and the public. In the energy sector this is relevant and necessary especially with regard to large energy production corporations and transmission networks operators.

Energy production in Germany used to be dominated by four big fossil fuel companies.14 While these companies have long underinvested in renewables they are now moving into the sector and threaten to privatise the future of the energy system. At the same time, these corporations still retain and are partly expanding their fossil assets and thus have a huge interest in maintaining fossil fuel production. Their investment in renewable energies is growing but contingent on future profits. A fast and socially just energy transition will not be possible without the assets as well as the knowledge and skills and labour of workers in the existing fossil sector. Rather than incentivising private actors and effectively subsidising private profits with public money, it would be more efficient to take companies into public ownership and directly finance the transition, especially if the social costs of the transition are taken into account.15 Socialisation and state financing of substantial investments in renewable capacities through democratically governed and publicly owned energy institutions could create quality, unionised jobs in the renewable sector and manage job losses in industries that need to be downscaled or phased out, such as lignite-mining or the automotive industry. In contrast, a transition based on private ownership will never be able to provide workers with secure pathways into future sectors. Socialised companies could also efficiently make the necessary investments, since they are not forced to provide a market return to shareholders, thereby reducing capital costs for the transition.

Socialisation not only involves the transfer of ownership but also critically includes democratic governance and a focus on public welfare. Socialised energy corporations would need to be governed by consumer representatives, environmental associations, and workers, with the state playing a minor role. At the same time, they would need to be anchored in clear public policy goals such as the provision of affordable energy, renewable investment targets, and knowledge transfer to the global South.

Socialisation presents a solution to similar issues concerning transmission grids. The German long-distance transmission network is currently divided among four private companies, funded through grid fees paid by consumers. These fees are determined by a state agency and include a significant return on equity. Consequently, shareholders of these companies receive a guaranteed profit, underwritten by consumers. At the same time there is a lack of investment, which creates regional imbalances and hampers the expansion of renewables. Instead of this, the long-distance transmission grid should be governed democratically at the national level. Governance of transmission networks should follow clear public and democratically set goals such as a needs-based expansion of renewable energy and be governed by workers and elected representatives.

The socialisation of big energy corporations and network operators needs to be complemented with public democratic ownership at the local level. Local and decentralised renewable production could be partially driven by energy cooperatives. In cities, elected energy councils could develop decarbonisation and energy-reduction plans to be implemented by democratised municipal utility providers. Public regional utilities could link local decarbonisation plans with the supra-regionally coordinated expansion of renewable energies and storage capacities.

A democratic energy transition in a socialised energy sector is thus underpinned by diverse models of democratic public ownership. The complexity of the energy system, with varying functions such as transmission, distribution, and production operating at different scales, calls for a multitude of democratic governance mechanisms and institutions.

Therefore, a socialised energy sector should be understood as an integrated, multi-tiered system featuring a wide variety of public and democratic ownership models that mutually reinforce and enhance each other.16 This isn’t just about ownership –it's about governance, participation, and accountability. It is also about creating structures where decision-making is shared and the benefits are distributed more equitably. This includes the socialisation of large energy companies and transmission operators, re-municipalisation of local grids and energy production as well as the support and promotion of small-scale local and cooperative ownership. It is about ensuring that the people who are affected by energy policies have a say in shaping those policies. Such an energy system has the potential to bring about the requisite energy transformation in a manner that is not only quicker and more efficient, but also more equitable. It's about crafting an energy future that prioritises the welfare of the public and the planet, ensuring that energy is accessible, affordable, and sustainable for all.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Socialisation as the core of an emancipatory alternative to green capitalism

This brief sketch of democratic energy transformation based on socialisation would obviously contrast immensely with currently dominant policy approaches. We propose that socialisation can be the core of an emancipatory project, which counters the current capitalist capture of the energy transformation. The transformation towards a state-led green capitalism is by no means a firmly established hegemonic project and there remain significant contradictions that provide opportunities for a new wave of struggles surrounding public ownership.

An emancipatory counter-project to green capitalism is still inadequately defined and organised, let alone sufficiently prepared to strategically generate counterbalancing power in the long term. The challenge of establishing such a hegemonic project is twofold. On the one hand, there is an ongoing need to resist the delays in the energy transition that the reactionary-fossilist faction is advocating (and, in part, to form necessary alliances with actors of the green-capitalist project). On the other hand, there is a need to articulate an inspiring and action-inspiring critique of the emerging green-capitalist project.

Even if this emancipatory alternative project is not yet fully established, there is currently fertile ground for new alliances. Pioneering projects such as the cooperation between Fridays for Future youth movement and the service sector union Ver.di for joint industrial action in the public transport sector give hope for a new phase of struggles in the mobility sector. In 2024, climate activists and trade unionists will once again unite, rallying for improved wages and increased investment in public transport. The turn of parts of the climate movement towards trade unions, as well as the corresponding climate turn in parts of the trade unions, could form the basis for further alliances. Already, the fractures and internal contradictions of green capitalism offer entry points to separate individual actors such as trade unions and, to some extent environmental associations from the green-capitalist project and win them over for Left–Green alliances.

Any successful political project requires a popular core that can provide an anchor for alliances. We are convinced that a radical public ownership agenda based on the socialisation of the energy transformation can form this popular core. Although an emancipatory political project will not achieve hegemony in the short term, there is a growing emphasis on building power around public ownership and socialisation. In the Rhineland, parts of the German climate movement are drawing inspiration from the successful Berlin expropriation initiative. The campaign ‘Expropriate RWE & Co.’ aims to socialise private energy infrastructure in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, challenging the two major energy corporations RWE and E.ON. They propose to transfer them into a public and democratic structure to drive the local energy transition. The initiative is working on legal possibilities for expropriation, as well as concepts for a democratised energy system, thereby doing pioneering work for a socialised energy sector. Other parts of the climate movement are also starting to develop strategies on socialisation in the context of the climate crisis (in the energy sector and beyond) and aim to spell out concrete campaign ideas at a strategy conference in early 2024.

The socialisation of energy transformation could present a unifying core for emancipatory politics, because it offers concrete improvements in people’s livelihoods by lowering and shifting transition costs, while providing a course of action that is commensurate with the scale of the climate crisis. Socialisation can and has been a successful and convincing campaign goal, as it allows the majority of the population so share in the gains of transformation, such as through cheaper electricity and energy prices (and in the long-term provision as a universal basic service). It thus offers an optimistic outlook to those currently suffering under neoliberal capitalism, demonstrating that even in the midst the climate crisis, substantial improvements in individual material living conditions can be achieved through collective solutionsrather than individual market-based ones.

Socialising energy corporations and transforming them together with workers in the sector, who provide both the knowledge and the power resources to do so, is necessary and possible. While there have been local and regional struggles surrounding re-municipalisation there is a lack of movement experience in fighting for and shaping public ownership at a level that responds to the climate crisis. With a socialisation agenda we can mould concepts of broad public ownership into concrete and achievable movement goals.

Socialisation, potentially through referenda, allows strategic entry into state-level terrain and power without necessarily assuming a political party form, thus laying the groundwork for alliances of diverse actors. Given the legal foundation for socialisation in Article 15 of the German Basic Law and the initial practical experiences gained through the Berlin expropriation movement, there is a unique opportunity to develop movement practice around establishing forms of democratic public ownership. This is crucial for social movements, which require not only well-articulated demands but also experiential spaces and practical forms.

In 2018, no one in Berlin thought that the expropriation of housing corporations would have the faintest chance of generating a public majority but today socialisation is a very real possibility and an unavoidable proposal in political discussions around the housing crisis. Social change can sometimes progress more rapidly than anticipated. If a similar dynamic can be generated in the energy sector, there might still be hope.