The UN Drug Control Conventions A Primer

Topics

For more than ten years, TNI’s Drugs & Democracy programme has been studying the UN drug control conventions and the institutional architecture of the UN drug control regime. As we approach the 2016 UNGASS, this primer is a tool to better understand the role of these conventions, the scope and limits of their flexibility, the mandates they established for the CND, the INCB and the WHO, and the various options for treaty reform.

Download PDF

-

Primer: The UN Drug Control Conventions (PDF, 875.93 KB)Average time to read: 1h minutes

Authors

- What are the UN drug control conventions and what is their purpose?

- What are the objectives of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs?

- What is the status of the coca leaf, opium poppy and cannabis in the 1961 Convention?

- What were the objectives of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances? What important agreements were reached with this new treaty?

- What were the objectives of the 1988 Convention? Why was another new treaty necessary?

- Do the treaties criminalise drug use and possession for personal use?

- Are the classified substances listed in the treaties’ Schedules ‘illegal’?

- Are the drug control conventions consistent with other UN treaties such as those concerning human rights?

- Which UN bodies are linked to the drug control conventions?

- Are the conventions an obstacle to progress on drug policies?

- Despite the rigidity of the conventions, have some countries been able to introduce the reforms they felt were necessary to solve their own drug-related problems?

- Is it realistic to expect that the conventions will be reformed?

- What are the options for a reform of the conventions?

- What are the possibilities for amending the conventions at the next UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs - UNGASS 2016?

- TNI publications on the UN drug control conventions

- Relevant publications on reforming the conventions

- Official United Nations documents

1. What are the UN drug control conventions and what is their purpose?

There are three United Nations treaties that together form the international law framework of the global drug control regime: the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, as amended by the 1972 Protocol; the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971, and the Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988.

The purpose of these treaties is to establish internationally applicable control measures with the aim of ensuring that psychoactive substances are available for medical and scientific purposes, while preventing them from being diverted into illegal channels. The treaties also include general provisions on the trafficking and use of psychoactive substances.

The 1961 and 1971 Conventions classify controlled substances in four lists or Schedules, according to their perceived therapeutic value and potential risk of abuse. Included in an annex to the 1988 Convention are two tables listing precursor chemicals, reagents and solvents which are frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances. This treaty also significantly reinforced the obligation of countries to establish criminal offences in order to combat all aspects of the illicit production, possession and trafficking of psychoactive substances.

Historical context that led to the conventions

To understand how the drug-related treaties came about, we need to refer to the historical and political context at the time they were adopted and the international events that preceded them. The proposal to create an international legal framework governing psychoactive substances was an initiative of the United States that dates back to the start of the 20th century and has gone through several stages since then.

In February 1909, amid growing concern about opium use in China, twelve countries met in Shanghai and set up the International Opium Commission to discuss the possibilities for imposing international controls on the opium trade for the first time. The delegates resolved – though without committing themselves – to put an end to the practice of smoking opium, restrict its use to medical purposes, and control its harmful by-products. No attempt was made at the time to apply criminal law in this regard.

This was the background to the first International Opium Convention (The Hague, 1912). This and other later treaties negotiated by the League of Nations (predecessor to the United Nations, 1919-1946) were normative rather than prohibitive in nature and their objective was to curb the excesses of an unregulated system of free trade. This meant that they imposed restrictions on exports but did not make it obligatory to declare drug use or cultivation illegal, let alone make these activities a criminal offence. Thus, the provisions they established for opiates, cocaine and cannabis did not involve criminalising either the substances themselves or their users or producers of their raw materials.

This was the reason why the two most 'prohibitionist' countries at the time, the United States and China, withdrew from the negotiations that led to the 1925 International Opium Convention, because they considered its measures to be insufficiently restrictive. On that occasion, the United States was aiming to secure not just the prohibition of drugs, but a ban on the production and non-medical use of alcohol, attempting to reproduce on an international scale its alcohol prohibition regime that remained in force from 1920 to 1933.

This attempt was thwarted because the United States did not have the support of the European colonial powers (France, Great Britain, Portugal and the Netherlands) whose overseas territories enjoyed a profitable monopoly on drugs (opium, morphine, heroin and cocaine) destined for the pharmaceutical market in Europe and the US.

Emerging from the Second World War as the dominant political, economic and military power, the United States was then in a position to forge a new drug control regime (the 1946 Lake Success Protocol) and apply the necessary pressure to impose it on other countries in the setting of the United Nations. The political climate enabled the globalisation of prohibitionist anti-drug ideals.

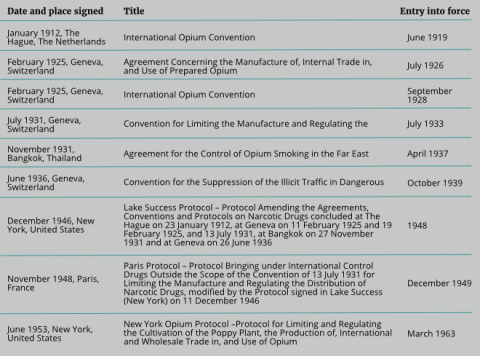

Treaties in force prior to the 1961 Single Convention

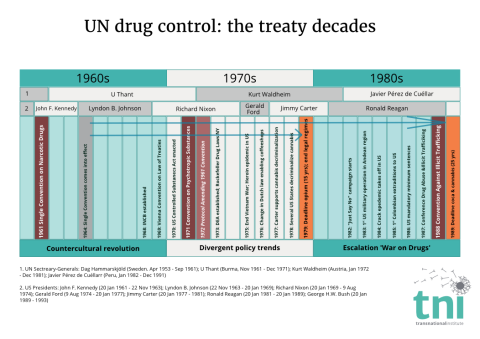

2. What are the objectives of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

?

The idea of having a Single Convention was once again an initiative of the United States, a country determined to impose a hard line on drugs on the rest of the world. The purpose of the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was to replace the previous international agreements that had been reached since the International Opium Convention in a not very systematic manner. It includes new provisions that did not appear in the previous treaties, and thus creates a unified, universal system of drug control. This system is clearly intolerant and prohibitionist concerning the production and supply of narcotic drugs, except for their production and supply for medical and scientific purposes.

The 1961 Single Convention expanded existing control measures to cover the cultivation of plants from which narcotics are derived. These provisions placed an especially heavy burden on the traditional producer countries in Asia, Latin America and Africa where the cultivation and widespread traditional use of opium poppy, coca leaf and cannabis were concentrated at the time. The Single Convention set the target of abolishing traditional uses of opium within 15 years, and traditional uses of coca and cannabis within 25 years. Given that the Convention entered into force in December 1964, the 15-year period for gradually eliminating opium use came to an end in 1979, while the 25-year deadline for coca and cannabis expired in 1989. Traditional practices including religious use and the widespread “quasi medical” use of the three plants had to be abolished.

The Single Convention created four lists or Schedules of controlled substances and established a process for including new substances in the Schedules without the need to modify the text of the treaty’s articles. The Convention’s four Schedules contain more than one hundred substances, which are classified according to the different degrees of control to which they must be subjected.

3. What is the status of coca leaf, opium poppy and cannabis in the 1961 Convention?

Some of the most controversial classifications in the Schedules are the inclusion of coca leaf in Schedule I and cannabis (cannabis and cannabis resin, and extracts and tinctures of cannabis) in Schedules I and IV. Schedule I contains the substances considered the most addictive and harmful. Schedule IV contains a small number of substances with “particularly dangerous properties” and with little or no therapeutic usefulness. With regard to Schedule IV narcotics in particular, Article 2, 5 (b) of the Convention says that “A Party shall, if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare, prohibit the production, manufacture, export and import of, trade in, possession or use of any such drug except for the amounts which may be necessary for medical and scientific research only…”.

It is important to highlight that, according to the Convention, the three plants also have licit purposes (medicinal, but also horticultural and industrial purposes) under certain conditions – see articles 21 bis to 28, which clarify these conditions. Article 23 also requires countries to set up a “government agency” to take charge of controlling the licit cultivation of opium poppy for medicines, and Articles 26 and 28 say that the same system of controls should also be applied to licit coca and cannabis cultivation. As for the coca leaf, Article 26 also says that “The Parties shall so far as possible enforce the uprooting of all coca bushes which grow wild. They shall destroy the coca bushes if illegally cultivated.” Further information on how exactly the Convention deals with these three substances can be found in the same articles 21 bis to 28.

The fact that special provisions on the cannabis plant, the opium poppy and the coca bush are included in the text of the treaty makes it more difficult to ease controls by only reclassifying them in the Schedules by means of the usual process, as described in Article 3 of the Convention. A country or the World Health Organisation (WHO) can propose to review a substance to consider its removal from the Schedules or move it to another one when they have information justifying such a rescheduling. In the case of cannabis, opium poppy and coca, a removal from the Schedules would not immediately end all international control and an amendment to the text of the treaty may be required as well.

4. What were the objectives of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances? What important agreements were reached with this new treaty?

The idea of negotiating this new treaty was to respond to the diversification of drug use, with the objective of controlling a whole new range of psychoactive substances (which became fashionable in the 1960s) such as amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines and psychedelic drugs, which were likewise classified in four Schedules.

During the negotiations on the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, it became evident that pressure was being exerted by the large pharmaceutical industry in Europe and the United States, which feared that its products would be brought under the same strict controls as those established by the Single Convention. The need for a new treaty was argued on the basis of a (scientifically questionable) distinction between the 'narcotics' controlled by the 1961 Convention and the so-called 'psychotropic substances', an invented concept without a clear definition. According to an employee of the UN Division of Narcotic Drugs and secretary of the Technical Committee of the Plenipotentiary Conference at the time: “The most important manufacturing and exporting countries tried everything to restrict the scope of control to the minimum and weaken the control measures in such a way that they should not hinder the free international trade… .” Compared to the strict controls that the Single Convention’s Schedules imposed on drugs derived from plants, the 1971 treaty established a less rigid control structure, except for Schedule I.

Schedule I includes substances said to pose a serious risk to public health, which are not currently recognised by the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) as having any therapeutic value. These include synthetic psychedelics such as LSD and MDMA, commonly known as Ecstasy. Schedule II includes amphetamine-type stimulants considered to have limited therapeutic value, as well as some analgesics and dronabinol* or tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), an important ingredient in cannabis. Schedule III includes barbiturate products with fast or average effects, which have been the object of serious abuse despite being therapeutically useful, as well as flunitrazepam and some analgesics such as buprenorphine. Schedule IV includes some weaker barbiturates such as phenobarbital, other hypnotics, hypnotic anxiolytics, benzodiazepines and some weaker stimulants.

See: the Schedules of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, as at 25 September 2013

The WHO and the classification of dronabinol/THC

Dronabinol (delta-9-THC), one of the active ingredients in cannabis was initially included in Schedule I (the most restrictive) but, following a recommendation by the WHO, in 1991 the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) reclassified it to Schedule II. Later scientific research by the WHO on dronabinolled the organisation to recommend a new reclassification in 2002 to move the substance into Schedule IV (the least restrictive).

The WHO Expert Committee stated at the time that “the abuse liability of dronabinol does not constitute a substantial risk to public health and society”. This recommendation was not taken up for political reasons, as some of the countries in the 2003 CND felt it was not appropriate to relax controls on the main active ingredient in cannabis.

A few years later, in 2007, the WHO updated its recommendation on dronabinol and asked again for it to be reclassified, this time to Schedule III. The issue was still highly controversial politically, however, and the CND therefore decided to postpone a decision, arguing that further assessment of the substance was required.

In 2012 the WHO Expert Committee once again recommended a schedule change, but the CND decided to not take it to a vote in 2013. The following year, the Netherlands pushed for a vote, mainly to uphold the basic principles of the CND scheduling procedure and to defend the important treaty mandate given to the WHO. The outcome of the vote, however, was that the CND did not adopt the WHO recommendation to de-schedule dronabinol.

5. What were the objectives of the 1988 Convention? Why was another new treaty necessary?

The 1988 Convention came about in the framework of the political, historical and sociological context of the 1970s and 1980s, leading to the adoption of more repressive measures. The increase in demand for cannabis, cocaine and heroin for non-medical purposes mainly in the developed world gave rise to large-scale illicit production in the countries where these plants had traditionally been grown, in order to supply the market. International drug trafficking quickly became a multi-billion-dollar business controlled by criminal groups. This rapid expansion of the illicit drug trade became the justification for intensifying a battle that soon became an all-out war on drugs. In the United States, which was the fastest-growing market for controlled substances, the political response was to declare war on the supply from abroad rather than analysing and addressing the causes of the burgeoning demand at home.

The term “war on drugs” was coined in 1971 by President Richard Nixon, making drugs (including their use) “public enemy number one” for the US. The first target in this war was Mexico, a country that had supplied the 1960s counter-cultural revolution with huge quantities of illegally-produced cannabis, and by 1974 had also become the main source of heroin for the US market. But the first military counternarcotic operations in this war took place in the Andes, with the deployment of US army special forces to provide training on how to destroy coca crops, cocaine laboratories and drug trafficking networks. The weakening of the fight against world communism and the end of the cold war in the late 1980s freed up large quantities of military assets that were then re-assigned to the war on drugs.

In the US halfway through the 1980s the crack epidemic took off; mandatory minimum sentences were introduced and mass incarceration started – especially of young black men. It was at this time, under significant pressure from the US for the rest of the world to join it in the war on drugs, that the United Nations convened another conference to negotiate what would become the Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988. The treaty obliged countries to impose criminal sanctions to combat all aspects of illicit drug production, possession and trafficking. It established special measures against the illicit cultivation, production, possession and trafficking of psychoactive substances and the diversion of precursor chemicals, as well as an agreement on mutual legal assistance, including extradition. Annexed to the 1988 Convention are two tables listing precursor chemicals, reagents and solvents which are frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances.

6. Do the treaties criminalise drug use and possession for personal use?

There is no specific obligation in the conventions to make drug use per se a criminal offence. Thus, drug use is not mentioned among the 'penal provisions' in the Single Convention (Article 36), or in the 1971 Convention (Article 22), or in Article 3 (Offences and Sanctions) of the 1988 Convention. This is related, firstly, to the fact that the treaties do not require countries to 'prohibit' any of the classified substances in themselves. The treaties only establish a system of strict legal control of the production and supply of all the controlled drugs for medical and scientific purposes, as well as introducing sanctions aimed at combating the illicit production and distribution of these same substances for other purposes.

The 1961 Convention only requires that the use of the drugs in Schedule IV (the most restrictive in this treaty) be prohibited if the Party should determine that “the prevailing conditions in its country” mean that this is “the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare” (Article 2 § 5 b). The 1971 Convention uses more robust terms than its predecessor, by prohibiting any use of the controlled substances in Schedule I (the most restrictive in this treaty) except for scientific purposes and “very limited medical purposes” (Articles 5 and 7), without mentioning whether this depends on its being “the most appropriate means” to protect public health.

Drug use was deliberately omitted from the articles listing the drug-related acts that must be declared a criminal offence. There is no doubt, then, that the UN conventions do not oblige countries to impose any penalty (criminal or administrative) for drug use as such. This is explicitly stated in the Commentary to the 1988 Convention regarding Article 3 of the Convention on “Offences and Sanctions”: “It will be noted that, as with the 1961 and 1971 Conventions, paragraph 2 does not require drug consumption as such to be established as a punishable offence”. The 1988 Convention does stipulate that a member state should consider possession for personal use as a crime but, even so, this provision is “subject to its constitutional principles and the basic concepts of its legal system”. [For further information on this subject, see the report, The development of international drug control, p. 8-10]

The conventions are more restrictive with regard to possession, acquisition, or growing for personal use. Article 33 of the 1961 Single Convention says that “The Parties shall not permit the possession of drugs except under legal authority” (and, in such authorised cases, solely for medical and scientific purposes) while Article 36, paragraph 1, obliges the Parties to declare possession a punishable offence. With regard to the obligation to criminalize possession, it is important to point out that a distinction is made between possession for personal use and possession for trafficking. The Convention’s emphasis on tackling trafficking may be understood to indicate that countries are not obliged by virtue of Article 36 of the 1961 Convention to declare simple possession a crime. This opinion is backed up by the history of the wording of Article 36, which was originally entitled “Measures against illicit traffickers”. A similar situation applies in the 1971 Convention, which takes its cue from the previous treaty.

In many countries, personal use is not in itself a crime. There are more and more countries in which the possession of a certain quantity of drugs for personal use is decriminalised, no longer a priority for the police, or subject to reduced sentences. These changes to the law or its enforcement in practice have had an immediate positive impact on the prison system in some countries, helping to alleviate the problem of overcrowding in prisons.

See more on this in: “Decriminalising possession for personal use,” Chapter 3 in The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition

7. Are the classified substances listed in the treaties’ Schedules ‘illegal’?

Contrary to what is commonly believed, none of the controlled drugs were declared 'illegal'. The drugs were only brought under different levels of control, depending on which Schedule they were classified in. The substances in themselves were not prohibited, but their production and trade was subjected to strict controls in order to limit their use to medical and scientific purposes. The oft-mentioned terms 'illegal drug' or ‘illicit drug’ do not actually appear in the UN conventions.

8. Are the drug control conventions consistent with other UN treaties such as those concerning human rights?

Human rights are explicitly mentioned only once in the three treaties: in Article 14(2) of the 1988 Convention. Although the protection of health and welfare might be considered the basic principles of the conventions, in practice the drug control system has resulted in human rights abuses across the globe. The treaties do not suggest that human rights principles should be infringed, but in the name of drug control fundamental rights (as established in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights) are being violated all over the world, including the right to life and to health, the right not to be subjected to torture or cruel treatment, the right to due process, the right to be free from discrimination, the economic, social and cultural rights of indigenous peoples, and children’s rights, among others.

In recent decades, the main strategy used to address drug-related problems has been based on repression. States have carried out military operations against small farmers growing drug-linked crops, used toxic chemicals to spray crops off the plants from which psychoactive substances are extracted, and forced rural communities off their land.

Some countries even impose the death penalty for drug offences. In its 2012 global overview report on the death penalty for drug offences, Harm Reduction International (HRI) identified 33 states and territories that still have the death penalty for drug offences on their statute books. Although fewer states actually use it, and fewer still carry out executions, between them they put hundreds of people to death every year. Indeed, the number of states prescribing the death penalty for drug offences actually increased after the 1988 Convention against trafficking was approved.

In Latin America, the enforcement of harsh laws on drugs has led to an increase in the percentage of people in prison for drug use and minor drug-related offences, as the report by TNI and WOLA on drug laws and prisons in Latin America shows. In Europe and Central Asia, one in every four women held in prison are there for non-violent drug offences. In Southeast Asia and China, hundreds of thousands of people are held for months – and sometimes years – in compulsory detention centres for drug users, where they are supposed to be given 'treatment'. In many of these centres no medical care is available, and the 'treatment' provided includes forced labour and physical and sexual violence. The detainees do not have access to due legal process or judicial review.

Many national laws continue to impose disproportionately long prison sentences for minor drug offences. Together with the use of the death penalty, this leads to a criminal justice system where minor drug offences are sometimes punished even more harshly than the crimes of rape, kidnapping or murder. In many countries, the disproportionately long sentences meted out to drug offenders causes prison overcrowding, ties up the criminal justice system, and places prisoners at greater risk of being infected by HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis and other diseases.

For further information on drug control and human rights, see Human rights and drug policy: guide to the key issues

9. Which UN bodies are linked to the drug control conventions?

The three conventions assign roles to the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), and the World Health Organization (WHO). To better understand what is involved in the mandates of each of these bodies, we describe them below:

9.1. Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND)

The CND is a multilateral forum established by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) as one of its technical commissions on 16 February 1946. The CND is the legislative and policy-making body, with 53 Member States, that assist the Council in supervising the application of the international drug control treaties. It also advises the Council on all matters related to the control of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and their precursors. The international drug control treaties assign the Commission on Narcotic Drugs important normative functions. These include the authority to study all matters related to the objectives of the conventions and ensure that they are enforced.

As the treaty enforcement body under the 1961 Convention and the 1971 Convention, the CND decides – based on WHO recommendations – on the classification of the narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances under international control. Thus, the CND and the WHO (as explained below) are the two bodies with the power to add or remove drugs from the lists of controlled substances and move them from one Schedule to another. In accordance with the 1988 Convention, following a recommendation by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), the CND decides on the precursor chemicals which are frequently used in the manufacture of internationally-controlled substances. The CND’s annual meetings in Vienna are a forum for nations to debate and pass resolutions on drug policies. [More information on the CND]

9.1.1. What are the main criticisms of the CND?

The CND is a political commission rather than a group of experts whose job it is to discuss and decide on best practices for all countries. Governments are represented in negotiations by officials from their ministries of foreign relations, home affairs, health, justice and defence, among others, or representatives from their diplomatic mission in Vienna. They often lack in-depth experience on drug policy issues and therefore are not always able to take the discussion forward.

Furthermore, all the decisions taken in the CND are the result of lengthy political negotiations and are adopted by consensus. This means that decisions are the product of the lowest common denominator in any discussion, and no country is able to alter any significant decision.

Other frequent criticisms of the CND point out that much of the CND’s official work is bureaucratic and involves taking a political stance. Debates in its plenary sessions do not in fact involve any debate, as they are essentially a succession of pre-prepared statements with predictable wording. Although the subject of drugs is closely related with other issues including human rights, health and development, the Vienna-based CND rarely coordinates with UN agencies in Geneva and New York such as UNAIDS, the Human Rights Council, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the WHO or the UN Development Programme (UNDP). Only recently has the CND started to improve mechanisms for civil society participation, though still to an insufficient extent.

9.2. International Narcotics Control Board, INCB (Mandate and functions)

The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) is an independent and quasi-judicial monitoring body, established by treaty, which is responsible for ensuring that the international drug control conventions are implemented. The Board was established in 1968 in accordance with the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. It had predecessors under the former drug control treaties, dating back to the time of the League of Nations.

Broadly speaking, INCB deals with the following:

- control and regulation of the licit manufacture of, trade in and use of drugs. INCB endeavours, in cooperation with Governments, to ensure that adequate supplies of drugs are available for medical and scientific uses and that the diversion of drugs from licit sources to illicit channels does not occur. INCB also monitors Governments’ control over chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of drugs and assists them in preventing the diversion of those chemicals into the illicit traffic.

- improving controls over the illicit manufacture of, trafficking in and use of drugs. INCB identifies weaknesses in national and international control systems and contributes to correcting such situations. INCB is also responsible for assessing chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of drugs, in order to determine whether they should be placed under international control.

More specifically, INCB is responsible for

- Administering a system of estimates of the global amounts of narcotic drugs

required for licit purposes, and a similar voluntary assessment system for required amounts of psychotropic substances. It also monitors licit production and trade of controlled substances through a system of export and import authorizations, with a view to assisting Governments in achieving a global balance between licit supply and demand.

- Monitoring and promoting measures taken by Governments to prevent the diversion of substances frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances and assesses such substances to determine whether there is a need for changes in the scope of control of Tables I and II of the 1988 Convention.

- Analysing information provided by Governments, United Nations bodies, specialized agencies or other competent international organisations, with a view to ensuring that the provisions of the international drug control treaties are adequately carried out by Governments, and recommending remedial measures.

- Maintaining a permanent dialogue with Governments to assist them in complying with their obligations under the international drug control treaties and, to that end, recommending where appropriate, technical or financial assistance should be provided.

INCB is required to ask for explanations in the event of apparent violations of the treaties, to propose appropriate remedial measures to Governments that are not fully applying the provisions of the treaties or are encountering difficulties in applying them and, where necessary, to assist Governments in overcoming such difficulties. If, however, INCB notes that the measures necessary to remedy a serious situation have not been taken, it may call the matter to the attention of the parties concerned, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs and the Economic and Social Council. As a last resort, the treaties empower INCB to recommend to parties that they stop importing drugs from a defaulting country, exporting drugs to it or both. In all cases, INCB acts in close cooperation with Governments. [Source: incb.org]

9.2.1. What are the main criticisms of the INCB?

Over the years, the INCB has been taking on a more political role with a very strict interpretation of the drug control conventions, passing judgement on sovereign states whose policies go in a different direction, and urging them to stay within the bounds of the conventions. In other words, the Board has exceeded its role as the body that monitors the UN conventions by making comments on matters that are the sole purview of national governments.

For example, ever since its 1992 report the INCB has been criticising the campaign to have coca leaf re-evaluated, led by Bolivia and Peru. Subsequent INCB reports have maintained this opposition. For example, then INCB president Hamid Ghodse wrote in the foreword to the 2011 Annual Report that “One major challenge to the international drug control system is the recent decision by the Government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia to denounce the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961(…). The Board has noted with regret that unprecedented step taken by the Bolivian Government and is concerned that, inter alia, while the denunciation itself may be technically permitted under the Convention, it is contrary to the fundamental object and spirit of the Convention.” Another more recent example is the INCB’s reaction to the proposal to regulate cannabis in Uruguay.

Furthermore, even though it has no authority to do so, the INCB has questioned recommendations made by the WHO, playing an increasingly active part in the discussions that lead to a decision on whether to reclassify the substances in the lists. It has even done this with regard to substances that are not internationally controlled, calling in its annual reports for them to be placed under control. A case in point is that of khat, a substance that, according to the WHO Expert Committee, does not need to be placed under international control. Nevertheless, in its 2006 report the INCB called upon “the authorities to consider taking appropriate measures to control [the] cultivation, trade and use” of khat.

In its 2010 report it complained that there are no controlled plants in the 1971 Convention. Being well aware that making recommendations on classification under the UN conventions is a mandate entrusted to the WHO, the INCB recommended to governments that they should consider controlling plant materials of this type within their own countries, thus contradicting the WHO experts’ advice which –in the case of khat for example- favoured educational measures over criminalisation.

The INCB also tends to go beyond its mandate with regard to the controversial issue of reforming the treaties. This is a particular concern now, when the international community needs technical assistance and advice rather than the simplistic response that “the treaties say no”. As mentioned before, the INCB is a monitoring body rather than a guardian of the conventions, and as such it ought to be working to reconcile differences between the member states’ positions and looking at the options that emerge as the debate progresses. But the debate itself about the best way for the global community to address the issue of drug use is not the INCB’s responsibility and belongs in other areas of the UN system: the General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the Commission on Narcotic Drugs.

The INCB is itself a creation of the conventions, and it derives from them not only its authority but its very existence. How, then, can it be expected to exercise impartial judgement in debates that call into question the conventions themselves?

9.3. World Health Organisation (WHO)

The role of the WHO is to assess the medicinal properties of a substance, from a public health perspective and on the basis of the best available evidence, and weigh the arguments that could lead to its use being controlled. The WHO should try to balance the need for a substance to be available for medical purposes with a consideration of the adverse effects that its non-authorised use may have on health. Under the 1961 and 1971 Conventions, the WHO is responsible for making recommendations to the CND on the classification of substances.

The WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence is in charge of reviewing substances for classification and advises the WHO Director-General on the recommendations to be made to the CND.

The Expert Committee undertakes two types of review in order to formulate its recommendations: a pre-review and a critical review. The pre-review is a preliminary exercise that is conducted with the aim of deciding whether or not a critical review is necessary. This will depend on whether the pre-review indicates that a substance should be classified under the terms of the conventions, but the pre-review itself is unable to make any recommendation on classification. The critical review process is a detailed exercise that involves looking at a substance’s chemical properties, pharmacology, toxicology, dependence and abuse potential, therapeutic uses, inclusion in the WHO model list of essential medicines, industrial uses, trade, impact on public health, dependence and unauthorised use, production and illicit trafficking, and other factors within an overall medical and public health perspective. The WHO Secretariat is responsible for gathering the necessary data for the critical review. It may request information from member states’ ministries of health and, when necessary, from ad hoc working groups.

10. Are the conventions an obstacle to progress on drug policies?

The conventions set out a 'one size fits all' arrangement with a rigid prohibitionist approach to drugs that every country in the world is expected to adopt. Some parts of the UN treaties are now outdated, no longer ‘fit for purpose’ to deal with new challenges and do not reflect the reality of today’s multicultural and multiethnic world. Legal tensions between national policy practices and the treaty framework are on the rise, especially in the area of cannabis regulation. This is why there is a need for a modernization of the treaty system that takes this new context into account and ensures that policy reforms can go ahead, guided by evidence and human rights principles but unhindered by legal constraints coming from outdated drug control treaties.

Although many government officials admit in private that the conventions are inconsistent and outdated, they hesitate to do so publicly because of the potential political costs that open dissent could imply for their countries. Thus, debate on the conventions has become a taboo issue. As most countries take their international law obligations seriously, including those derived from the drug control treaty regime, the conventions do represent an obstacle for alternative drugs policies that fall outside of the conventions’ limited flexibility and room for manoeuvre.

For example, when the Jamaican Minister of Justice explained the decision to decriminalise the possession of up to two ounces of cannabis and to permit the use of cannabis for medical and religious purposes, he underscored that “Jamaica is a small independent country that believes in the rule of law. Given our size and limited resources, our national security and territorial integrity depend on upholding the rule of law in the international sphere, and we have always respected and complied with our international obligations, just as we expect others to do the same. Therefore, in considering any change to the law relating to ganja, it is critical that regard must be had to obligations under the relevant international agreements to which Jamaica is signatory. These agreements place certain limitations on the changes that can be made to our domestic law without violating our international obligations.”

11. Despite the rigidity of the conventions, have some countries been able to introduce the reforms they felt were necessary to solve their own drug-related problems?

With the scaling up of the war on drugs and the toughening of drug laws after the 1988 Convention, an increasing number of countries started to turn away from the conventions’ repressive approach in practice and presented various proposals for reform at the national level.

To start with, the drive for reform was concentrated in European countries, Canada and Australia, where harm reduction programmes (including needle exchange, methadone substitution therapy, safe consumption rooms, etcetera) gradually became an accepted component of these countries’ policies on drugs. A second type of national-level reform is decriminalisation. In several countries, the possession of psychoactive substances for personal use is no longer a crime. A third type of reform involves a shift by the criminal justice system towards social and health care measures for non-violent offenders whose problem use of psychoactive substances drove them to commit minor crimes. Fourthly, some countries have started to review their drug laws and law enforcement practices with the aim of introducing the principles of human rights and proportionality in sentencing.

The purpose of all these efforts is to de-escalate the war on drugs and to 'humanise' drug control policies. In the last few years, this reformist tendency has become particularly evident in some Latin American countries, where major proposals to reform drug control laws have been implemented recently or are being discussed.

But although these reforms have provoked tensions with the treaty system, they are all justifiable within the existing flexibility of the treaties and they represent a gradual change in the way the treaties are being interpreted, taking advantage of the gaps and ambiguities in their text.

There are however also clearly established limits to the latitude of the treaties; especially the legal regulation under state control of a market for recreational purposes falls outside the realm of interpreting the treaties in good faith. For that, changes of the treaty obligations are required, either by amendments to the conventions themselves or by exceptions for specific countries via reservations. The most relevant case of the latter is Bolivia: because of its interest in defending the traditional uses of coca leaf, the country withdrew in 2011 from the 1961 Convention and later re-adhered to it with a reservation allowing the domestic legal coca market to persist. While the move was contested by the INCB on dubious grounds, and the G8 countries and a few others formally objected to Bolivia’s reservation, the procedure was accepted by the UN, creating a precedent that could be used in other circumstances.

12. Is it realistic to expect that the conventions will be reformed?

As the first UN World Drug Report stated in 1997, “Laws – and even the international Conventions – are not written in stone; they can be changed when the democratic will of nations so wishes it.” Argentina recently echoed that statement at the General Assembly in May 2015: "Let’s not be afraid to debate… even about the conventions that apparently need to be untouchable. The conventions are not the Bible, they are just that, conventions, agreements, which should evolve as people and policies evolve". Indeed, significant changes have already been made to them once, by the so-called 1972 Protocol which amended the 1961 Single Convention. Thus, the current text of the Single Convention is substantially different to what was agreed in 1961. Why would it be so inconceivable to do that again?

Most other international treaty regimes have built-in monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, for example regular Conferences of the Parties (COPs) to review implementation problems encountered by the parties. But the three drug control conventions lack such mechanisms to enable evolution of the system over time.

Until recently, even discussing a reform of the conventions was a political taboo that was informally accepted as necessary to preserve the delicate Vienna consensus in the area of drug control. Over the last decade, however, the cracks that have opened up in this consensus have widened, so much so that in the case of cannabis regulation in Uruguay and the US states of Washington, Colorado, Oregon and Alaska we can now talk in terms of breaches of the treaties. This shows that today’s criticisms of the current international drug control framework are not confined to whispered conversations in the CND corridors but have entered the realm of radical policy shifts away from the treaty regime’s prohibitionist paradigm.

Even so, a genuine process to review the conventions has not yet begun. The risk of delaying this step for too long is that the tensions between the conventions and the decisions and practices adopted by individual countries are becoming ever stronger, causing political friction between some nations and others, as well as between the UN bodies and those governments who have dared to propose and implement measures that conflict with the treaties. All this goes against what is after all the purpose of an international treaty: to reconcile differences and unite the community of nations around points of common agreement among them all, however difficult that may be.

13. What are the options for a reform of the conventions?

There are several ways to modify either the conventions themselves, the range of substances they control, or the obligations for a specific state party or for a group of countries. Putting in practice any of these options implies significant procedural complications and political obstacles. None of the options offers an easy escape from the demands of the current treaties, which prohibit a shift to legal regulation. For good reasons, therefore, a number of US states and Uruguay have moved forward with cannabis regulation before finding a legal solution to the problem of infringing the treaty system, and several more are likely to follow before any treaty reform actually takes place. As is often the case, a critical mass of discrepancy between law and practice needs to be reached before political conditions enable actual legislative reforms at the national or -even more so- at the international level.

Amendments

Any state party can propose an amendment to the 1961, 1971 or 1988 Convention, and if such a proposed amendment has not been rejected by any party within 18 months (24 months in the case of the 1988 Convention), it automatically enters into force. If objections are submitted, ECOSOC must decide if a conference of the parties need be convened to negotiate the amendment.

Other options are less clear, but if only a few or minor objections are raised, the Council can decide to accept the amendment in the understanding it will not apply to those who explicitly rejected it. If a significant number of substantial objections are tabled, the Council can reject the proposed amendment. In the latter case, if the proposing party is not willing to accept the decision, it can either denounce the treaty or a dispute may arise which could ultimately “be referred to the International Court of Justice for decision” (Single Convention, Article 48).

The amendment procedure has been invoked twice in the case of the drug control conventions: in 1972 a Conference of the Parties negotiated and adopted a whole series of substantial amendments to the 1961 Single Convention; and in 2009 Bolivia proposed an amendment to delete the obligation contained in article 49 to abolish coca chewing. The Bolivian amendment failed after 18 countries objected and Bolivia decided not to pursue the case but instead denounce the treaty and re-adhere with a reservation that had a similar effect but only for Bolivia.

Reservations

At the moment of signing, acceding or ratifying a treaty, states have the option to make reservations regarding specific provisions, as many countries in fact did in the case of all three drug control treaties [reservations can be found in the UN Treaty Collection database]. Reservations or other formal unilateral “interpretive declarations” are meant to exclude or modify the legal effect of certain provisions of a treaty for the reserving state.

The issuing of “late reservations” (after having already adhered to a treaty) has been subject to debate among legal scholars and in the UN International Law Commission, and current practice of the UN treaty depository is to only accept them if none of the other state parties object. The procedure of treaty denunciation followed by reaccession with reservation, as Bolivia did, is a legitimate procedure, although its practice in international law is limited to exceptional cases. According to Yale Law Professor Laurence R. Helfer, “a categorical ban on denunciation and reaccession with reservations would be unwise. Such a ban would [...] force states with strongly held objections to specific treaty rules to quit a treaty even when all states (and perhaps non-state actors as well) would be better off had the withdrawing state remained as a party. It would also remove a mechanism for reserving states to convey valuable and credible information to other parties regarding the nature and intensity of their objections to changed treaty commitments or changes in the state of the world that have rendered existing treaty rules problematic or inapposite.”

Rescheduling

The 1961 and 1971 conventions mandate the WHO to review substances and recommend their appropriate scheduling, weighing evidence of health risks against their medical usefulness. The treaties require the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), contrary to its current self-imposed modus operandi to negotiate resolutions until full consensus is reached, to vote on WHO recommendations.

The 1961 Convention requires a simple majority vote among CND’s 53 member states to adopt a WHO (re)scheduling recommendation; the 1971 Convention requires a two-third majority. Any state party can request a substance to be reviewed by the WHO and significant changes in the UN drug control treaty system could thus be adopted without reaching consensus among all the state parties, for example if the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence would recommend to remove cannabis from the treaty schedules (or move it to a lower control category).

Several substances, in fact, have never been reviewed by the WHO, including cannabis, coca leaf, cocaine, opium and morphine. There was “a common political feeling” at the time that they should be scheduled, but a group of WHO-related experts recently exposed that “we have no proof of a scientific assessment”. From an evidence-based point of view as well on treaty procedural grounds, the legitimacy of their current classification is therefore questionable.

The process of scheduling under the current treaty system has become a political battlefield, due to inconsistencies in the treaties themselves and infringements on the WHO mandate from the side of the INCB.

Denunciation

The 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties stipulates that a historical “error” and a “fundamental change of circumstances” are valid reasons for a member state to revoke its adherence to a treaty. In light of the ‘Jurassic’ nature of the drug control treaties and the seemingly insurmountable procedural and political obstacles to change them, the question is often raised why countries should not simply ignore or withdraw from the UN drug control treaty regime.

States remain party to the treaties for a number of reasons, one of which is that the UN drug control treaties also regulate the global trade in drugs for licit medical purposes, including substances on the WHO list of essential medicines. Adequate access to controlled medicines is already a big problem in most developing countries, and withdrawing from the INCB-administered global system of estimates and requirements operating under the UN drug control conventions would risk making it even worse.

Also, being party to all three of the drug control conventions is a condition in a number of preferential trade agreements or for accession to the European Union. Denunciation can therefore have political and economic consequences beyond drug control, especially for less powerful countries.

Modifications inter se

The 1969 Vienna Convention also offers an interesting and hitherto little-explored legal option in Article 41: “Two or more parties to a multilateral treaty may conclude an agreement to modify the treaty as between themselves alone”, providing that the modification in question “does not affect the enjoyment by the other parties of their rights under the treaty or the performance of their obligations” and is not “incompatible with the effective execution of the object and purpose of the treaty as a whole.”

This option could perhaps provide a legal basis for justifying international trade between national jurisdictions that permit or tolerate the existence of a licit market for a particular substance, even though that international trade is not permitted under the UN treaty obligations. It could apply, for example, to the import of hashish from Morocco to supply Spain’s cannabis clubs or the coffee shops in the Netherlands. It could also apply to the export of coca leaf from Bolivia – a country where growing and trading in the leaf in its natural form is legal – to countries such as Argentina or Ecuador, where the use of coca leaf is also legal under the country’s domestic laws. An agreement between countries like these to modify the treaty and permit trade among themselves would be difficult to challenge with the argument that it affects the rights of other parties.

In theory, a group of countries seeking to resolve the dilemma of legal non-compliance with the treaties in the case of cannabis regulation (as is currently the case with Uruguay and the U.S.) could make use of an inter se modification. If other countries should decide to follow in their footsteps, they could form a group of like-minded countries and sign an agreement with each other to modify or annul the provisions in the UN conventions related to the control of cannabis but only among themselves.

All the provisions in the treaties –including on cannabis- would remain in force vis-à-vis the treaty’s signatory parties that are not part of the inter se agreement. Over time, such an inter se agreement might evolve into an alternative treaty framework to which more and more countries could adhere, while avoiding the cumbersome process of unanimous approval of amendments to the current regime.

Martin Jelsma

14. What are the possibilities for amending the conventions at the next UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs - UNGASS 2016?

The question appearing on the international agenda is no longer whether or not there is a need to reassess and modernize the UN drug control system, but rather when and how. The question is if a mechanism can be found soon enough to deal with the growing tensions and to transform the current system in an orderly fashion into one more adaptable to local concerns and priorities, and one that is more compatible with basic scientific norms and UN standards of today.

The Commentary on the Single Convention (on p. 462-463) mentions an option that seems intriguing in view of the forthcoming UNGASS in 2016: “the General Assembly may itself take the initiative in amending the Convention, either by itself adopting the revisions, or by calling a Plenipotentiary Conference for this purpose.” Thus, the General Assembly could in fact adopt amendments to the treaties by a simple majority vote, “always provided that no amendment, however adopted, would be binding upon a Party not accepting it.”

That will definitely not happen, however, at the UNGASS on 19-21 April 2016 in New York. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged member states to use UNGASS 2016 “to conduct a wide-ranging and open debate that considers all options”, but meanwhile heavily negotiated CND and GA resolutions already require the UNGASS outcomes to remain “within the framework of the three international drug control conventions and other relevant United Nations instruments”.

If opening an honest debate about the conventions appears to be politically impossible, thereby blocking the prospect of an evolution of the treaty regime, the international drug control system will become more and more polluted with legally untidy “flexible interpretations” – precisely what is happening right now. There are good reasons why countries shouldn’t stretch treaties beyond acceptable bounds, as it undermines respect for international law in general.

With the door to opening the debate about treaty reform at the UNGASS already basically closed, the best option in terms of the UNGASS outcomes might be to at least agree to establish an Expert Advisory Group to recommend how to deal with these complex issues, which are unlikely to result in a satisfactory consensus at the special session itself, in the years following the 2016 UNGASS and preparing for the next UN high-level review in 2019.

TNI publications on the UN drug control conventions

For more than ten years, TNI’s Drugs and Democracy programme has been studying the drug control conventions and developments regarding drug policies in the UN setting. During this time, we have produced a wide range of publications on these treaties. For further information and discussion on the matters raised in the 14 key questions in this primer, we recommend reading the following reports:

Prospects for Treaty Reform and UN Coherence on Drug Policy. Improving Global Drug Policy: Comparative Perspectives and UNGASS 2016, May 2015

The International Drug Control Regime and Access to Controlled Medicines, Drug Law Reform Series No 26, December 2014

The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition, Drugs Special Reports, March 2014

Towards revision of the UN drug control conventions. The logic and dilemmas of Like-Minded Groups. Drug Law Reform Series No 19, March 2012

The Limits of Latitude, Drug Law Reform Series No 18, March 2012

Treaty guardians in distress - The inquisitorial nature of the INCB response to Bolivia, Paper by Martin Jelsma, July 2011

Fifty years of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs: a reinterpretation, Drug Law Reform Series No 12, March 2011

Lifting the ban on coca chewing. Bolivia's proposal to amend the 1961 Single Convention, Drug Law reform Series No 11, March 2011

The Development of International Drug Control. Lessons learned and strategic challenges for the future. Paper by Martin jelsma for the Global Commission on Drug Policy , February 2011

Drug policy reform in practice: Experiences with alternatives in Europe and the US, Paper by Tom Blickman and Martin Jelsma, July 2009

Vienna Consensus on Drug Policy Cracks, Article by Tom Blickman, April 2009

Rewriting history: A response to the 2008 World Drug Report, Drug Policy Briefing No 26, June 2008

Sending the wrong message. The INCB and the un-scheduling of the coca leaf, Drug Policy Briefing No 21, March 2007

The United Nations and Harm Reduction - Revisited. An unauthorised report on the outcomes of the 48th CND session. Drug Policy Briefing No 13, April 2005

The Global Fix: The Construction of a Global Enforcement Regime, Crime & Globalisation Series, October 2005

The United Nations and Harm Reduction, Drug Policy Briefing No 12, March 2005

Challenging the UN drug control conventions. Problems and possibilities - Special Issue on the UNGASS Mid-term Review. By David Bewley-Taylor, International Journal of Drug Policy (Volume 14, Issue 2) March 2003

Change of Course: An Agenda for Vienna, Drugs & Conflict Debate Papers No 6, March 2003

The erratic crusade of the INCB, Drug Policy Briefing No 4, February 2003

Breaking the Impasse: Polarisation and Paralysis in UN Drug Control, Drugs & Conflict Debate Paper No 5, July 2002

New Possibilities for Change in International Drug Control. Drug Policy Briefing No 1, December 2001

See also our United Nations Drug Control Watch website

Relevant publications on reforming the conventions

UNGASS 2016: Prospects for Treaty Reform and UN System-Wide Coherence on Drug Policy. By Martin Jelsma. Brookings Institution, May 2015

IDPC response to the 2012 Annual Report of the International Narcotics Control Board - August 2013

Rewriting the UN Drug Conventions. A Beckley Foundation Report by Prof Robin Room and Sarah MacKay. Beckley Foundation, April 2012

Roadmaps for reforming the UN Conventions, Beckley Foundation, 2012

The development of international drug control: lessons learned and strategic challenges for the future. By Martin Jelsma - Global Commission on Drug Policies, January 2011

Official United Nations documents

Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, as amended by the 1972 Protocol

Commentary on the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961

Commentary on the Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961

Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971

Commentary on the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971

Challenges and future work in the review of substances for possible scheduling recommendations. March 2014

Evolution of International Drug Control 1945-1995, UNODC 1999