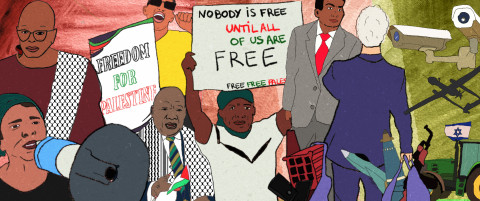

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

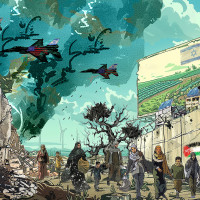

Regiones

In response to the Tufan Al-Aqsa (Al-Aqsa Flood, October 7 2023) and the escalating Israeli genocidal attacks on Palestinians in Gaza in subsequent days and months, many African countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, have taken a stand for Palestine, with widespread support across the continent for the Palestinian cause and condemnation of Israeli crimes in Gaza. This support comes in a context of changing attitudes to Palestine on the continent. Over the past 50 years, evolving circumstances have reshaped African approaches to the issue, with the historical principles of African unity, once rooted in revolutionary liberation movements and South–South solidarity, being eroded. At the same time, Israel has successfully established diplomatic relations with 44 African countries, which has challenged the maintenance of a unified African stance on Palestine.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

2. Israel as the empire’s gateway to Africa

It is impossible to understand current African positions on the Palestinian cause—both official and popular—without taking account of Israeli penetration of Africa over the years. Firstly, Israeli activity has frequently aligned with neocolonial efforts on the African continent, with Israel acting as a bridge between former colonial industrial nations and developing countries in Africa. Secondly, this activity reflects Zionist efforts to cultivate allies and garner political support for Israel within global forums. Thirdly, Israel seeks to bolster its economy and to secure foreign markets across Africa.

Prior to recent discoveries of oil and gas reserves in the Mediterranean, Israel did not have any significant natural resources. The mineral wealth it controls in the occupied territories primarily consist of copper, phosphate and Dead Sea salts (with technological assistance from the United States (US) and Europe being instrumental in exploiting these resources).6 Africa, on the other hand, is abundant in mineral treasures and raw materials, which are coveted by Israel and former colonial Western powers. Moreover, seeking to expand its economy by positioning itself as an industrial hub that can advance both its own interests and those of its European and American supporters, Israel has therefore leveraged its presence in Africa to enhance these countries’ relations with African nations and to exploit Africa as a market for Israeli products.

In the two decades following its establishment in 1948, Israeli was engaged in absorbing, housing and finding employment for new immigrants, particularly those from impoverished Afro-Asian countries. Demographically, the Jewish population in Palestine numbered no more than 650,000 in 1948. By 1962, this number had risen to over 2 million,7 and it reached 2.3 million by 1966. During this period, Israel actively encouraged the immigration of African Jews from countries such as Nigeria, Ethiopia and Lesotho to the occupied territories.

The insights of African Jews arriving from various African countries helped the Israeli Foreign Ministry understand the challenges these nations were facing, and they helped Israeli intelligence to identify influential figures in African countries who might support Zionist interests. African Jewish Zionists played a crucial role in promoting Israel’s political goals. Through institutions like the Jewish Agency, Israel implemented specialised programmes involving diaspora Jews, including those from Africa. Its diplomatic missions across Africa arranged for African Jews to visit the occupied territories and attracted Zionist volunteers who had finished their military service in the Israeli Occupation Force (IOF) to go and join mercenary groups in various African countries.8

Against this background of its desire to expand both its Jewish population and its economy, Israel leveraged the wave of independence from colonialism that began in 1960, which became known as the Year of Africa. The retreating colonial powers left behind them newly independent African countries that were often in a state of need, scarcity and confusion, grappling with internal and external challenges, including border disputes, the complexities of modern governance, economic underdevelopment, a lack of economic growth, difficulties in integrating the global community and establishing an autonomous international personality, and a lack of skilled personnel for modern nation-building. Israel capitalised on these challenges. Swiftly seeking recognition from these new nations and establishing diplomatic relations with them, it entered into economic agreements, enhanced technical and cultural cooperation, and dispatched experts to provide assistance in various sectors.9 At the same time, Israel provided the former colonial powers with an alternative means to safeguard their remaining interests on the continent.

It is important to note in this regard that even before their departure, these colonial powers had sought to link African countries with Israel through economic agreements and had fostered personal relationships between African leaders and Israeli representatives. They permitted Israeli government officials and the Histadrut (the General Federation of Labour in Israel) to exploit African lands that were previously under colonial control, and they facilitated contacts between Israeli professional bodies and student organisations and their counterparts in Africa. This support persisted after African countries gained independence.10

3. Early developments in Israeli–African ties

Over time, Israel development of its relations with African countries took a unique course. It began by studying the continent's conditions and identifying the best opportunities to infiltrate and create a conducive environment for an Israeli presence. Much of what it aimed for was achieved by 1967, which marked the peak of Israeli activity in Africa. However, it also marked the beginning of a significant deterioration in Afro-Zionist relations.

The history of Israeli–African relations can be divided into five phases: the reconnaissance phase (1948–1956); the penetration and creation of sympathy phase (1957–1962); the support phase (1962–1967); the deterioration phase (1967–1978); and finally, the Arab retreat phase, involving the normalisation agreements. This section discusses the first three of these phases.

In its early years, Israel lacked the political influence to make inroads into the African continent. At any rate, its focus at this time was on strengthening its relations with the major powers, with African countries considered of secondary importance. This changed after the Bandung Conference of 1955, which Israel perceived as a blow that further isolated it from Afro-Asian countries.11 The conference's resolution on Palestine showed that these countries supported the Arab view on the Palestinian question, as it excluded Israel from attending. In response to the conference, Israel decided to counter the Arab efforts at isolating it by focusing on forming connections with liberal Afro-Asian countries and nations seeking national liberation.

The danger of being isolated from the countries of the global South was brought home to Israel when these countries supported Egypt during the Tripartite Aggression (Suez Crisis of 1956), and this danger was also apparent in the political agreement and cohesion shown by the Bandung bloc at the UN, which was particularly evident at the 1956 Brioni Meeting. This bloc viewed Israel as a tool representing the old colonialism. Furthermore, Egypt's unequivocal stance against US military policy in the Middle East also heightened Israel's fears at this time, due to the ideological clarity of such a stance and the potential growth of such opposition across the region. Indeed, Israel understood that the decline of Western influence in the Middle East would pose a significant threat to its existence, especially during the early years after its establishment.12

However, despite these considerations, Israel's early contacts with the African continent were infrequent and limited. They included contacts with Liberia and Ethiopia, which were under local imperial authoritarian rule at this time, and the signing of trade agreements with the colonial authorities in Kenya, Nigeria, Madagascar and Gabon.

The first support Israel received from Africa was Liberia’s 1947 vote in favour of the UN Partition Plan (with the apartheid government in South Africa also voting in favour). Israel opened an embassy in Monrovia in 1954 and it further penetrated Liberia through informal relations. In 1955, the first two companies involving Zionist and Liberian capital were established in Monrovia. These were two branches of Mayer Investments in Tel Aviv: one engaged in construction and reconstruction and the other in capital investment.13 However, although Liberia was the first African nation with which Israel signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation, its official stance towards Israel was often cautious and reserved. Nevertheless, just as Burma formed the cornerstone of Zionist relations in Asia, Liberia played a similar role in Africa.

The benefits Israel gained from its early relationship with some African countries were significant: these early connections helped it to understand the African context and paved the way for deeper engagement with other African countries.

For its part, Ethiopia abstained from voting on the UN partition resolution in 1947 and it delayed recognising Israel until 1961,14 despite the two countries’ ongoing cooperation in the economic, cultural and scientific fields. The reason was its conflict with Eritrea, in relation to which it hoped to gain the support of Egypt, Sudan and other African countries that supported Palestine. It was only after the 1967 Arab defeat that Israel was able to gain access to Ethiopia and East Africa, through the port of Eilat.

After the 1956 war, Israel's strategy was put to the test, and it made significant modifications to its goals and positions regarding the continent. This period saw an intensification of high-level missions and visits by Israeli officials to Africa. The wave of independence that swept across African countries in 1960 bolstered Israeli diplomacy on the continent. Israel was keen to strengthen its pre-independence relationships with some African countries and to secure official recognition from newly independent states through diplomatic missions. Additionally, Israel sought to establish new relations with countries with which it had not previously engaged.

Israeli Chief of the General Staff Moshe Dayan visited Liberia and Ghana in 1957, while in 1958, Minister of Foreign Affairs and later Israel’s fourth Prime Minister Golda Meir visited Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal and Côte d'Ivoire, marking the first high-level Israeli official visits to the continent. In discussions with African leaders during these visits, Meir highlighted Israel’s commitment to providing aid to these nations. She also extended invitations to several African heads of state to visit the occupied territories, with some doing so in 1958 and 1959. These visits were motivated by these governments’ interest in learning about Israel’s development experience, which was widely discussed in the African press.15

In addition, Israel significantly enhanced its diplomatic relations with Ghana between 1957 and 1959, and in February 1959 it expanded its diplomatic presence on the continent by establishing a consulate in Senegal and an embassy in Guinea, which was under French colonial rule at the time.

When Guinea declared independence from France and exited French West Africa (Afrique-Occidentale française) in 1958, Israel faced a dilemma: while it was eager to strengthen its presence in Africa, it hesitated to recognise Guinea, fearing repercussions from France, which was a key ally and supporter. Israel opted to postpone recognition, while emphasising its dedication to building cooperative relations with Guinea across all fronts. Diplomatic ties were only established in 1959,16 after Zionist diplomats succeeding in convincing the French government of the strategic significance of recognising Guinea's independence for Israeli security and bolstering its influence in Africa.

During this period, much of the African press, which was owned by foreign companies and was subject to colonial censorship and other authoritarian measures, expressed widespread sympathy towards Israel. This favourable environment mobilised many writers who were eager to promote Israel as they were invited to visit and meet with its officials. This effort ultimately cultivated a segment of African public opinion that was sympathetic towards Israel and these journalists were pivotal in countering anti-Israel propaganda emanating from Arab embassies and anti-Zionist African countries across the continent.

Visits by Africans to Israel focused on a number of fields that were of particular importance to African countries. For example, early in 1959, missions from Niger and Chad arrived in Israel to observe its achievements in agriculture and social work. In November 1959, a delegation of Guinean trade unions visited Israel to study its cooperative and economic movements, and this was followed by another visit by a Guinean trade union delegation funded by Israel, which lasted six months. Israel was particularly well received in West African Francophone countries due to its close ties with France. This was demonstrated by the visit of the President of Gabon to the occupied territories in 1961.17 Continued Israeli–French cooperation indicated France’s tacit approval for Israel's involvement in Francophone countries.

4. The Rise and fall of Zionist influence in Africa

Israeli–African relations reached their peak in the late 1960s. Convinced of the view that this strategic depth was inherently linked to its security and its ability to expand militarily, during the years leading up to the 1967 war, Israel made significant efforts to strengthen its ties with East African countries and to establish new contacts and agreements with leaders of national movements in regions of Africa that had not yet gained independence. In particular, it focused on regions adjacent to the Red Sea, which it perceived to be a vital corridor.

However, while 1967 marked the peak of Israeli activity in Africa, it also marked the beginning of a decline in Afro–Israeli relations. There were many overlapping reasons for this decline that contributed to revealing Israel’s expansionist intentions in Africa.

Several financial and economic factors prevented Israel from achieving the influence it sought in the late 1960s. Firstly, it lacked funding: at this time, it mainly relied on foreign aid to cover its trade deficit, which prevented it from meeting African countries' demand. A shortage of funding also affected its ability to bear the financial expenses of diplomatic missions to Africa, sending experts, receiving African trainees, and providing loans and subsidies. The aftermath of the Six-Day War of June 1967 saw a decline in tourism rates, and in the flow of foreign capital and private investment, which led to accumulating internal and external debts, industrial bottlenecks and an inability to meet export needs, resulting in inflation. Taxes increased, and there was a significant shortage of foreign exchange reserves. These financial problems prevented Israel from fulfilling its contracts with, and commitments to, African countries.

Additionally, Israel's involvement within Africa encountered other problems. Some agricultural projects (such as projects in Gabon, Côte d'Ivoire and Liberia) that were similar to those applied in the occupied territories failed as they were not well-suited to Africa’s social, political and environmental conditions. Too-rapid implementation also led to significant failures of some Israeli projects, which damaged the reputation of Zionist companies and institutions, sometimes leading to contracts with African countries not being renewed. For example, during the construction of the airport in the Ghanaian capital, Accra, Israel did not follow the agreed-upon specifications. A similar situation occurred with regard to the construction of the parliament building and town hall in Monrovia. Furthermore, Israel found itself unable to meet African countries’ growing demand for technical expertise, especially engineers and nurses, while at the same time, the African economies lacked trained manpower, modern equipment, and internal communication, which hindered some joint projects. Moreover, Israeli experts working in African countries faced difficulties in adapting to the social climate and challenges of daily life: in addition to the language barrier, they exhibited racism, kept to themselves and did not integrate socially.

In addition, after 1967, African countries began to realise Israel’s true stance on many African issues, including independence. For example, Israel supported secession/separatist movements in Nigeria, Congo, Angola and Mozambique, and cooperated with apartheid regimes in southern Africa (Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe). African public opinion began to condemn Israel’s inconsistent positions on African issues, viewing Israel as complicit with counterrevolutionary forces that were opposed to liberation movements on the continent.

5. Anti-Zionist stances in Africa

The current normalisation of relations with Israel adopted by some African countries, after an earlier period of boycott, and their retrogressive positions, are neither predetermined nor spontaneous: they are political choices stemming from the ideology and the class composition and orientation of the African ruling classes.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) played a progressive role in supporting the Palestinian cause. On 5 June 1967, in the immediate aftermath of the Zionist aggression against neighbouring Arab countries, Guinean leader Ahmed Sékou Touré convened the political bureau of the Democratic Party of Guinea, which made the decision to sever diplomatic relations with Israel, expelling the Israeli ambassador, along with Zionist experts and technicians.18 This stance resonated with the leaders of other OAU member states and the OAU Ministerial Council in Addis Ababa subsequently called on all member states to provide material and moral support to Egypt and other Arab countries, describing Israel as a belligerent entity. This decision sparked backlash among Zionist circles, who called for cutting aid to African countries that supported the OAU's stance.

Held in Algeria in September 1968, the Sixth OAU Conference demanded the withdrawal of foreign forces from all Arab territories occupied in June 1967, in accordance with Security Council Resolution 242. The conference also appealed to all OAU member states to exert their influence to ensure the implementation of the resolution. The following year, in Addis Ababa, the Seventh Conference included the Middle East crisis as a stand-alone agenda item for the first time. It emphasised the need to implement the decision adopted at the 1968 Algeria session and reaffirmed this commitment in subsequent sessions. At the Ninth Congress in 1971, the OAU intensified its efforts by establishing a committee of 10 African countries dedicated to resolving the Middle East crisis. The OAU urged all member states to support Egypt and mobilise in international forums, including the Security Council and the General Assembly, for the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of Israel from the additional territories occupied in 1967.19

The Eleventh Conference, held in May 1973, marked a significant shift in Afro–Arab relations. During this session, the OAU recognised that respecting the rights of the Palestinian people is essential for any just and equitable solution to the Middle East crisis. Moreover, it warned Israel that its policies and practices might compel OAU member states to take political or economic measures against it, either individually or collectively, at the African level.

Subsequently, the African boycott movement expanded to include Guinea, Uganda, the People's Republic of Congo, Mali, Chad, Niger, Burundi, Togo and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Each country had its own reasons for severing relations with Israel, in addition to their position on the Palestinian cause. For example, the Ugandan Government considered the Israeli embassy in its capital, Kampala, responsible for subversive activities against it, including illegally introducing large numbers of Zionists into the country, as well as selling it defective weapons.20 In the People's Republic of Congo, the Marxist political regime saw Israel as a bastion of American imperialism in the Middle East, while Chad feared that the presence of Israelis on its territory endangered not only its own security but also that of neighbouring African countries. For its part, Burundi was convinced that Israel supported rebels who had tried to seize power in May 1973.

Five decades later, we still observe similar dynamics, albeit less pronounced ideologically. On 20 February 2024, at the initiative of Algeria and South Africa, the African Union Commission (AUC), the successor to the OAU, withdrew Israel's observer member status, permanently banning it, just two years after that status had been conferred on Israel, following a decade of diplomatic efforts. AUC Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat described the situation in the Gaza Strip as the “most flagrant violation” of international humanitarian law and accused Israel of seeking to “exterminate” Gaza's inhabitants.21

6. African revolutionaries and the Palestinian question

In 1965, during the Second Conference of the Nationalist Organisations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP) in Dar es Salaam, Amílcar Cabral addressed the question of Palestine. Speaking on behalf of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde, the Portuguese National Liberation Front and the Committee for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe, he stated: “We firmly support Arab and African countries in their efforts to help the Palestinian people regain their dignity, independence and right to life.”22

Two decades later, on 4 October 1984, at the UN General Assembly, Burkinabe revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara delivered a speech in solidarity with the Palestinian people: “I think of the valiant Palestinian people, the families which have been splintered and split up and are wandering throughout the world seeking asylum. Courageous, determined, stoic and tireless, the Palestinians remind us all of the need and moral obligation to respect the rights of a people.”23

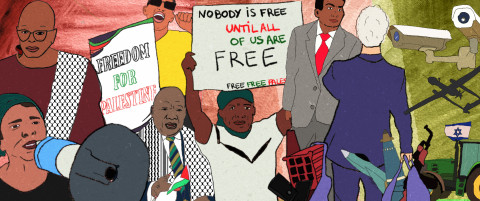

Nelson Mandela likewise supported the Palestinian cause. He condemned Israel's apartheid regime and stated that the question of Palestine was the “greatest moral issue of our time” and that South Africa's “freedom [was] incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinian people.”24

Walter Rodney, the Afro-Guyanese historian, was also supportive of Palestine. While living in Tanzania he wrote an article for The Standard magazine about the plane hijackings carried out by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).25 He argued that these hijackings boosted the morale of the oppressed and secured the international community’s attention to their cause. In his piece, Rodney praised the young guerrilla Leila Khaled, who led several hijackings on behalf of the PFLP, describing her as “an example of a woman liberated through struggle”. Rodney saw hijacking as a tactic used by Palestinian guerrillas to bring attention to their demand for a one-state solution, which was being ignored by the West and opposed by Israel. Rodney's comments are highly relevant today: they provide insight into the reasoning behind the recent actions of the Palestinian resistance movement.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

7. African Solidarity: grassroots and institutional support for Gaza/Palestine

The 54 African countries constitute a significant voting bloc in all international forums, including the UN Security Council and General Assembly, as has been seen in the various resolutions proposed and adopted since 7 October 2023 concerning a ceasefire/humanitarian truce in Gaza. Despite the fact that a minority of these 54 countries oppose Hamas’s resistance and support the Israeli occupation army, this bloc, in its overwhelming majority, voted in favour of various General Assembly resolutions calling for a humanitarian truce or a ceasefire and upgrading Palestine's rights in the United Nations as an Observer State. Importantly, to the exception of Liberia, no African country has voted against any UN resolution related to a ceasefire, the declaration of a humanitarian truce and the unimpeded delivery of humanitarian aid to Gaza.

These votes have taken place in the context of a rising movement, beginning in 2021, advocating for African values and Pan-Africanism in the Sahel and West Africa, which has seen protests against both the Western presence—particularly of France and the US—in these countries and normalisation with Israel. Notably, the protests in Senegal in 2023 and 2024 focused on achieving greater economic and monetary sovereignty and solidarity with Palestine. A specific focus of this movement has been reconsidering relations with France, particularly concerning dependence on the franc zone, which is controlled by France. At the same time, the ongoing war in Ukraine has strained the West’s financial resources, thereby underscoring Africa's crucial role in the global economy and its potential to influence future international alliances. In fact, this has led global powers to make efforts to re-engage with African countries and to mitigate their losses from the war through energy and weapons cooperation agreements with these countries.

In this context, the genocide in Gaza has spurred a reconsideration among African public opinion regarding the Palestinian cause leading to mounting opposition to normalisation with Israel and a growing wave of public anger across African countries against Israel, the US and their Western allies involved in the Gaza genocide. As a result, concerns have been raised about potential targeting of Western interests and individuals on the continent by disgruntled protesters and groups. For example, the US State Department, via the US Embassy in Abuja, has issued a travel advisory for Americans planning to travel to Nigeria, cautioning about possible attacks by hostile crowds.

Conclusion

The large wave of solidarity with Palestine across many countries of the Global South has been accompanied by a strong recognition of the hollowness and bankruptcy of the imperial “rules-based international order”, which further undermined any remaining legitimacy of the global North as regards the application of international law. Specifically, the European powers, notably the United Kingdom and Germany, are finding themselves increasingly isolated—alongside the US—for openly supporting Israel's genocidal war on Gaza. Despite some internal differences within the Western bloc, its geopolitical strategies are increasingly diverging from those of the world majority, a fact that has been most clearly evidenced by the consistent political and moral support shown by most of the global South towards the Palestinian cause.

This divergence is also present within Western countries themselves. The US’s decision to consistently veto all Security Council resolutions (up until the resolution of 25 March 2024, on which it abstained), and to provide an additional $17 billion in military aid to Israel, is in contradiction to increasing domestic voices opposed to such support, including the powerful and widespread pro-Palestine student movement on American universities’ campuses. These internal developments have undermined mainstream perceptions regarding the Western liberal democracy.

The history of the peoples of the global South and of the global labour and student movements illustrate how collective efforts, even if gradual, strengthen an ever-growing solidarity with Palestine. Rooted in shared experiences and a commitment to confronting historical injustices, these movements are challenging the moral authority claimed by the West, and promise transformative change across the globe, from North to South.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

-

Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

Fecha de publicación:

-

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

Fecha de publicación:

-

Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Fecha de publicación:

-

Sustainability fantasies/genocidal realities Palestine against an eco-apartheid world

Fecha de publicación:

-

Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

Fecha de publicación:

-

From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024

Fecha de publicación:

-

The circus of academic complicity A tragicomic spectacle of evasion on the world stage of genocide

Fecha de publicación:

-

India, Israel, Palestine New equations demand new solidarities

Fecha de publicación: -

Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation

Fecha de publicación:

-

From the Favelas and Rural Brazil to Gaza How militarism and greenwashing shape relations, resistance, and solidarity with Palestine in Brazil

Fecha de publicación: