Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

An alternative approach to understanding Palestine – one that is framed by the wider region and the Middle East’s central place in our fossil fuel-centred world.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Post-War Transformations and the Middle East

Two major global shifts defined the changing world order in the years immediately following the Second World War. The first was a revolution in the world’s energy systems: the emergence of oil as the world’s principal fossil fuel, displacing coal and other energy sources across the leading industrialised economies. This fossil fuel transition occurred first in the US, where the consumption of oil surpassed coal in 1950, followed by Western Europe and Japan in the 1960s. Across the wealthy countries represented in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), oil made up less than 28% of total fossil fuel consumption in 1950; by the end of the 1960s, it held a majority share. With its greater energy density, chemical flexibility, and easy transportability, oil powered a booming post-war capitalism – underpinning a range of new technologies, industries, and infrastructure. This was the beginning of what scientists would later describe as the ‘Great Acceleration’ – a massive and continued expansion of fossil fuel consumption that began in the mid-twentieth century, and which has led inexorably to today’s climate emergency.

This global transition to oil was closely connected to a second major post-war transformation: the consolidation of the US as the leading economic and political power. The economic rise of the US had begun in the early decades of the twentieth century, but it was the Second World War that marked the definitive emergence of the US as the most dynamic force in global capitalism, opposed only by the Soviet Union and its allied bloc. American power arose on the back of the destruction across Western Europe during the war, coupled with the weakening of European colonial rule over much of the so-called Third World. As Britain and France faltered, the US took the lead in shaping the architecture of post-war politics and economics, including a new global financial system centred on the US dollar. By the mid-1950s, the US held a 60% share of world manufacturing output and just over a quarter of global GDP – and 42 of the top 50 industrial corporations in the world were American.

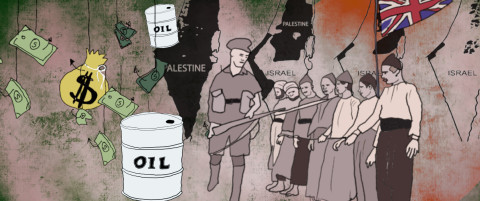

These two global transitions – the transition to oil and the ascendance of American power – had profound implications for the Middle East. On one hand, the Middle East played a decisive role in the global shift to oil. The region had plentiful oil supplies, amounting to nearly 40% of the world’s proven reserves by the mid-1950s. Middle East oil was also located close to many European countries, and the costs of producing it were much lower than the costs of oil production anywhere else in the world. Seemingly unlimited quantities of low-cost Middle East oil could thus be supplied to Europe at prices lower than coal, while ensuring that domestic US oil markets remained insulated from the effects of increased European demand. The recentring of Europe’s oil supply on the Middle East was a remarkably rapid process: between 1947 and 1960, the share of Europe’s oil that originated from the region doubled, rising from 43% to 85%. This not only enabled the emergence of new industries (such as petrochemicals) but also new forms of transport and war-making. Indeed, without the Middle East, the oil transition in Western Europe may never have happened.

Most of the Middle East’s oil reserves are concentrated in the Gulf region, especially Saudi Arabia and the smaller Gulf Arab states, as well as Iran and Iraq. Through the first half of the twentieth century, these countries had been ruled by autocratic monarchies supported by the British (except for Saudi Arabia, which was nominally independent of British colonialism). Oil production in the region was controlled by a handful of large Western oil firms, who paid rents and royalties to the rulers of these states for the right to extract oil. These oil firms were vertically integrated, meaning they not only controlled the extraction of crude oil, but also the refining, shipping, and sale of oil around the world. The power of these firms was immense, with their control of the infrastructures of oil’s circulation allowing them to exclude any potential competitors. The concentration of ownership in the oil industry far exceeded that seen in any other industry; indeed, at the end of the Second World War, more than 80% of all the world’s oil reserves outside the US and USSR were controlled by just seven large American and European firms – the so-called ‘Seven Sisters’.1

Israel and the Anti-Colonial Revolt

Despite their huge power, as the Middle East became the centre of world oil markets through the 1950s and 1960s, these oil firms were faced with a major problem. As took place elsewhere around the world, a range of powerful nationalist, communist, and other left-wing movements challenged rulers who were backed by British and French colonialism, threatening to upset the carefully constructed regional order. This was experienced most sharply in Egypt, where the British-supported monarch, King Farouk, was ousted in 1952 in a military coup led by a popular military officer, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser’s coming to power forced the withdrawal of British troops from Egypt and led to Sudan obtaining independence in 1956. Egypt’s newly gained sovereignty was crowned with the nationalisation of the British/French-controlled Suez Canal in 1956 – an action celebrated by millions of people across the entire Middle East and met with a failed invasion of Egypt by Britain, France, and Israel. As Nasser took these steps, anti-colonial struggles were growing elsewhere in the region, most notably in Algeria, where a guerrilla war for independence was launched against the French occupation in 1954.

Although it is often overlooked today, these threats to longstanding colonial domination were likewise felt across the oil-rich states of the Gulf. In Saudi Arabia and the smaller Gulf monarchies, support for Nasser ran high, and various left-wing movements protested the venality, corruption, and pro-Western stance of the ruling monarchies. The potential consequences of this were demonstrated in neighbouring Iran, where a popular national leader, Mohammed Mossadegh, had come to power in 1951. One of Mossadegh’s first acts was to take over the British-controlled oil company, Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (the forerunner of today’s BP) in the first oil nationalisation in the Middle East. This nationalisation resonated strongly in nearby Arab states, where the slogan ‘Arab oil for the Arabs’ gained widespread popularity amid the general anti-colonial mood.

In response to Iran’s oil nationalisation, US and British intelligence officials orchestrated a coup against Mossadegh in 1953, bringing to power a pro-Western government loyal to the Iranian monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The coup marked the opening salvo in a sustained counter-revolutionary wave directed against radical and nationalist movements across the region. The overthrow of Mossadegh also demonstrated a major shift in the regional order: while Britain played an important role in the coup, it was the US that took the lead in planning and carrying out the operation. This was the first time the US Government had deposed a foreign ruler during peacetime, and the CIA’s involvement in the coup was an important precursor of later US interventions, such as the 1954 coup in Guatemala and the overthrow of Chile’s Salvador Allende in 1973.

It was in this context that Israel emerged as a major bulwark of American interests in the region. In the early years of the twentieth century, Britain had been the principal supporter of Zionist colonisation of Palestine and, after Israel’s establishment in 1948, it continued to support the Zionist state-building project. But as the US supplanted British and French colonial dominance in the Middle East during the post-war period, American support for Israel emerged as the lynchpin of a new regional security order. The key turning point was the 1967 war between Israel and leading Arab states, which saw the Israeli military destroy the Egyptian and Syrian air forces and occupy the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the (Egyptian) Sinai Peninsula, and the (Syrian) Golan Heights. Israel’s victory shattered the movements of Arab unity, national independence, and anti-colonial resistance that had crystallised most sharply in Nasser’s Egypt. It also encouraged the US to become the country’s primary patron, replacing Britain. From that moment onwards, the US began to supply Israel annually with billions of dollars’ worth of military hardware and financial support.

The Significance of Settler Colonialism

The 1967 war demonstrated that Israel was a powerful force that could be used against any threats to American interests in the region. But there is a crucial dimension to this that often goes unremarked: Israel’s special place in supporting American power is directly connected to its internal character as a settler colony, founded on the ongoing dispossession of the Palestinian population. Settler colonies must continually work to fortify structures of racial oppression, class exploitation, and dispossession. As a result, they are typically highly militarised and violent societies, which tend to be reliant upon external support, which allows them to maintain their material privileges in a hostile regional environment. In such societies, a substantial proportion of the population benefits from the oppression of indigenous peoples and understands their privileges in racialised and militaristic terms. For this reason, settler colonies are much more dependable partners of Western imperial interests than ‘normal’ client states.2 This is why British colonialism supported Zionism as a political movement in the early twentieth century – and why the US embraced Israel in the post-1967 moment.

Of course, this does not mean that the US ‘controls’ Israel, or that there are never differences of opinion between the US and Israeli governments over how this relationship should be sustained. But Israel’s ability to maintain a permanent state of war, occupation, and oppression would be deeply imperilled without continuous American backing (both materially and politically). In return, Israel serves as a loyal partner and a bulwark against threats to American interests in the region. Israel has also acted globally in supporting repressive US-backed regimes across the world – from Apartheid South Africa through to military dictatorships in Latin America. Alexander Haig, US secretary of state under Richard Nixon, once put it bluntly: ‘Israel is the largest American aircraft carrier in the world that cannot be sunk, does not carry even one American soldier, and is located in a critical region for American national security.’3

The connection between the internal character of the Israeli state and its special place in American power is akin to the role that South African apartheid played for Western interests across the African continent. There are important differences between South African apartheid and Israeli apartheid – not least the preponderant share of South Africa’s black populations in the country’s working class (unlike Palestinians in Israel) – but as settler colonies, both countries came to act as core organising centres of Western power in their respective neighbourhoods. If we examine the history of Western support for South African apartheid, we see the same sorts of justifications that we see today in the case of Israel (and the same kinds of attempts to block international sanctions and criminalise protest movements). These parallels extend to the role of specific individuals. One little-known example of this is a trip made by a young member of Britain’s Conservative Party to South Africa in 1989, during which he argued against international sanctions on South Africa and made the case for why Britain should continue to support the Apartheid regime. Decades later, that young Tory, David Cameron, now holds the position of UK Foreign Minister – and is one of the key world leaders cheerleading Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

The Middle East’s centrality to the global oil economy gives Israel a more pronounced place in imperial power than was held by Apartheid South Africa. But both cases demonstrate why it is so important to think about how regional and global factors intersect with the internal class and racial dynamics of settler colonies.

Israel’s Economic Integration into the Middle East

The Middle East became even more significant to American power following the nationalisation of crude oil reserves across most of the region (and elsewhere) during the 1970s and 1980s. Nationalisation brought the longstanding direct Western control of Middle East crude supplies to an end (although American and European firms continued to control most of the global refining, transport, and sale of this oil). In this context, US interests in the region revolved around guaranteeing the stable supply of oil to the world market – denominated in US dollars – and ensuring that oil would not be used as a ‘weapon’ to destabilise the American-centred global system. Moreover, with Gulf oil producers now earning trillions through the export of crude, the US was also deeply concerned about how these so-called petrodollars circulated through the global financial system – a matter that is directly consequential to the dominance of the US dollar.

In pursuing these interests, US strategy became fully focused on the survival of the Gulf monarchies, led by Saudi Arabia, as key regional allies. This was particularly important following the overthrow, in 1979, of Iran’s Pahlavi monarchy, which had been another mainstay of American interests in the Gulf since the 1953 coup. US support to the Gulf monarchs was manifested in a variety of ways – including the sale of massive amounts of military hardware that turned the Gulf into the largest market for weapons in the world, economic initiatives that channelled Gulf petrodollar wealth into American financial markets, and a permanent US military presence that continues to form the ultimate guarantee of monarchical rule. A pivotal moment in the US–Gulf relationship came with the Iran–Iraq War, which lasted between 1980 and 1988, and ranks as one of the most destructive conflicts of the twentieth century (up to half a million people perished). During this war, the US supplied weapons, funding, and intelligence to both sides, viewing it as a way to sap the power of these two large neighbouring countries and further ensure the security of the Gulf monarchs.

In this manner, US strategy in the Middle East came to rest upon two core pillars: Israel, on one side, and the Gulf monarchies, on the other. These two pillars remain the crux of American power in the region today; however, there has been a critical shift in how they relate to one another. Beginning in the 1990s, and continuing through to the current moment, the US Government has sought to knit these two strategic poles together – along with other important Arab states, such as Jordan and Egypt – within a single zone that is tied to US economic and political power. For this to happen successfully, Israel needed to be integrated into the wider Middle East – by normalising its relations (economic, political, diplomatic) with Arab states. Most importantly, this meant getting rid of the formal Arab boycotts of Israel that had existed for many decades.

From Israel’s perspective, normalisation was not simply about enabling Israeli trade with, and investments in, Arab states. Following a major recession in the mid-1980s, Israel’s economy had shifted away from sectors such as construction and agriculture, towards a much greater emphasis on high-tech, finance, and military exports. Many leading international companies, however, were reluctant to do business with Israeli firms (or inside Israel itself) because of the secondary boycotts imposed by Arab governments.4 Dropping these boycotts was essential in order to attract big Western firms into Israel, and also to enable Israeli firms to access foreign markets in the US and elsewhere. Economic normalisation, in other words, was just as much about ensuring Israeli capitalism’s place in the global economy as it was about Israel accessing markets in the Middle East.

To this end, the US (and its European allies) employed a variety of mechanisms from the 1990s onwards aimed at driving forward Israel’s economic integration into the wider Middle East. One was the deepening of economic reforms – an opening up to foreign investment and trade flows that spread rapidly across the region. As part of this, the US proposed a range of economic initiatives that sought to tie Israeli and Arab markets to one another, and then to the US economy. A key scheme involved the so-called Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs) – low-wage manufacturing zones established in Jordan and Egypt in the late 1990s. Goods produced in the QIZs (mostly textiles and garments) were given duty-free access to the US, provided that a certain proportion of the inputs involved in their manufacture came from Israel. The QIZs played an early and decisive role in bringing together Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian capital in joint ownership structures – normalising economic relations between two of the Arab states that neighbour Israel. By 2007, the US Government was reporting that more than 70% of Jordan’s exports to the US came from QIZs; for Egypt, 30% of exports to the US were produced in QIZs in 2008.5

Alongside the QIZ programme, the US also proposed the Middle East Free Trade Area (MEFTA) initiative in 2003. MEFTA aimed to establish a free trade zone spanning the entire region by 2013. The US strategy was to negotiate individually with ‘friendly’ countries using a graduated six-step process that would eventually lead to a full-fledged free trade agreement (FTA) between the US and the country in question. These FTAs were designed so that countries could connect their own bilateral FTAs with the US with other countries’ bilateral FTAs, thereby establishing sub-regional-level agreements across the Middle East. These sub-regional agreements could be linked over time, until they covered the entire region. Importantly, these FTAs would also be used to encourage Israel’s integration into Arab markets, with each agreement containing a clause committing the signatory to normalisation with Israel and forbidding any boycott of trade relations. While the US failed to meet its 2013 goal for establishing MEFTA, the policy successfully drove an expansion of US economic influence in the region, underpinned by normalisation between Israel and key Arab states. Strikingly, today the US has 14 FTAs with countries across the world, of which five are with states in the Middle East (Israel, Bahrain, Morocco, Jordan, and Oman).

The Oslo Accords

However, the success of economic normalisation ultimately hinged upon there being a change in the political situation that would give a Palestinian ‘greenlight’ to Israel’s economic integration into the wider region. Here, the key turning point was the Oslo Accords, an agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that was signed under the auspices of the US Government on the White House lawn in 1993. Oslo built heavily upon colonial practices established over preceding decades. Since the 1970s, Israel had attempted to find a Palestinian force that would administer the West Bank and Gaza Strip on its behalf – a Palestinian proxy for the Israeli occupation that could minimise day-to-day contact between Palestinians and the Israeli military. These early attempts collapsed during the First Intifada, a large-scale popular uprising that began (in the Gaza Strip) in 1987. The Oslo Accords brought the First Intifada to an end.

Under Oslo, the PLO agreed to constitute a new political entity, called the Palestinian Authority (PA), which would be granted limited powers over fragmented areas of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The PA would be completely dependent upon external funding for its survival – especially loans, aid, and import taxes collected by Israel that would then be remitted to the PA. Because most of these funding sources ultimately derived from Western states and Israel, the PA was quickly politically subordinated. In addition, Israel retained full control over the Palestinian economy and resources, and the movement of people and goods. After the territorial division of Gaza and the West Bank in 2007, the PA established its headquarters in Ramallah in the West Bank. Today, the PA is headed by Mahmoud Abbas.6

Despite the way the Oslo Accords and subsequent negotiations are typically presented, they were never about peace and a road to Palestinian freedom. It was under Oslo that Israeli settlement expansion exploded in the West Bank, the Apartheid Wall was built, and the elaborate movement restrictions that govern Palestinian life today developed. Oslo served to cast key segments of the Palestinian population – refugees and Palestinian citizens of Israel – out of the political struggle, reducing the question of Palestine to negotiations around slivers of territory in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Most importantly, Oslo provided a Palestinian blessing to Israel’s integration into the wider Middle East, opening the way for Arab governments – led by Jordan and Egypt – to embrace normalisation with Israel under a US umbrella.

It was after Oslo that the movement restrictions, barriers, checkpoints, and military buffers that now encircle Gaza emerged. In this sense, the open-air prison that is today Gaza is itself a creation of the Oslo process: a direct thread connects the Oslo negotiations to the genocide we are now witnessing. It is crucial to remember this in the light of ongoing discussions about possible post-war scenarios. Israeli strategy has always involved the periodic use of extreme violence, twinned with false promises of internationally backed negotiations. These twin tools are part of the same process, serving to reinforce the continued fragmentation and dispossession of the Palestinian people. Any post-war negotiations steered by the US will certainly see similar attempts to ensure Israel’s continuing domination of Palestinian lives and land.

Thinking Forward

The strategic centrality of the oil-rich Middle East in American global power explains why Israel is now the largest cumulative recipient of US foreign aid in the world, even though it ranks as the world’s 13th wealthiest economy by GDP per capita (higher than the UK, Germany, or Japan). It also explains the bipartisan support for Israel among political elites in the US (and UK). Indeed, in 2021 – under the Trump presidency and before the current war – Israel received more US foreign military financing than all other countries in the world combined. And, crucially, as the last eight months have shown, American support extends far beyond financial and material support, with the US acting as the final backstop in defending Israel politically on the world stage.7

As we have seen, this American alliance with Israel is not incidental to the dispossession of the Palestinian people, but is actually grounded in it. It is Israel’s settler-colonial character that has given it such an outsized role in bolstering US power across the region. This is why the Palestinian struggle is such a core part of driving political change across the Middle East – a region that is now the most socially polarised, economically unequal, and conflict-affected in the world. And, conversely, it is why the struggle for Palestine is intimately bound up with the successes (and failures) of other progressive social struggles in the region.

The central axis of these inter-regional dynamics remains the connection between Israel and the Gulf states. In the two decades that followed the Oslo Accords, US strategy in the Middle East continued to emphasise Israel’s economic and political integration with the Gulf states. A major step forward in this process occurred with the 2020 Abraham Accords, which saw the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain agree to normalise relations with Israel. The Abraham Accords paved the way for a UAE–Israel FTA, signed in 2022, which was Israel’s first FTA with an Arab state. Trade between Israel and the UAE surpassed $2.5 billion in 2022, up from just $150 million in 2020. Sudan and Morocco have also reached similar agreements with Israel, driven forward by significant American inducements.8

With the Abraham Accords, five Arab countries now have formal diplomatic relationships with Israel. These countries encompass around 40% of the population across the Arab world, and include some of the region’s leading political and economic powers. But one crucial question still remains: when will Saudi Arabia join this club? While it is impossible that the UAE and Bahrain could have agreed to the Abraham Accords without Saudi Arabia’s consent, the Saudi Kingdom has so far not formally normalised ties with Israel – despite a plethora of meetings and informal connections between the two states over recent years.

Amidst the current genocide, a normalisation deal between Saudi Arabia and Israel is undoubtedly the principal goal of US planning for the post-war moment. It is very likely that the Saudi government would agree to such an outcome – and it has probably indicated as much to the Biden administration – provided it receives some sort of go-ahead from the PA in Ramallah (perhaps connected to international recognition of a Palestinian pseudo-state in parts of the West Bank). There are obviously significant obstacles to this scenario, including the ongoing refusal of Palestinians in Gaza to submit and the question of how Gaza will be administered following the end of the war. But the current US plan of a multinational Arab force taking control of the Strip, headed by some of the leading normalising states – the UAE, Egypt, and Morocco – would likely be connected to Saudi–Israeli normalisation.

Bringing the Gulf states and Israel together is increasingly crucial to US interests in the region, given the sharp rivalries and geopolitical tensions emerging at the global level, especially with China. While there is no other ‘great power’ that is set to replace American dominance in the Middle East, there has been a relative decline in US political, economic, and military influence across the region over recent years. One indication of this is the growing interdependencies between the Gulf states and China/East Asia, which now go far beyond the export of Middle East crude. In this context – and given the longstanding place of Israel in American power – any normalisation process steered by the US state would help reassert American primacy in the region, potentially serving as a crucial lever against China’s influence there.

Nonetheless, despite the ongoing discussions around post-war scenarios, the last 76 years have repeatedly demonstrated that attempts to permanently erase Palestinian steadfastness and resistance will fail. Palestine now sits at the forefront of a global political awakening that exceeds anything seen since the 1960s. Amidst this heightened awareness of the Palestinian condition, our analysis must go beyond immediate opposition to Israel’s brutality in the Gaza Strip. The struggle for Palestinian liberation sits at the centre of any effective challenge to imperial interests in the Middle East, and our movements need a better grounding in these wider regional dynamics – especially the pivotal role of the Gulf monarchies. We also need a deeper understanding of how the Middle East fits within the history of fossil capitalism and contemporary struggles for climate justice. The question of Palestine cannot be separated from these realities. In this sense, the extraordinary battle for survival waged by Palestinians today in the Gaza Strip represents the leading edge of the fight for the future of the planet.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

-

Framing Palestine Israel, the Gulf states, and American power in the Middle East

Fecha de publicación:

-

African attitudes to, and solidarity with, Palestine From the 1940s to Israel’s Genocide in Gaza

Fecha de publicación:

-

Failing Palestine by failing the Sudanese Revolution Lessons from the intersections of Sudan and Palestine in politics, media and organising

Fecha de publicación:

-

Sustainability fantasies/genocidal realities Palestine against an eco-apartheid world

Fecha de publicación:

-

Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

Fecha de publicación:

-

From Global Anti-Imperialism to the Dandelion Fighters China’s Solidarity with Palestine from 1950 to 2024

Fecha de publicación:

-

The circus of academic complicity A tragicomic spectacle of evasion on the world stage of genocide

Fecha de publicación:

-

India, Israel, Palestine New equations demand new solidarities

Fecha de publicación: -

Ecocide, Imperialism and Palestine Liberation

Fecha de publicación:

-

From the Favelas and Rural Brazil to Gaza How militarism and greenwashing shape relations, resistance, and solidarity with Palestine in Brazil

Fecha de publicación: