Abolitionist creativity How intellectual property can hack digital power

Corporations’ wealth is increasingly built on intangible intellectual property (IP) rights rather than hard assets. What if we could hack these legal and economic codes that underpin capitalism so that they are based on human rights, worker solidarity, ecological sustainability and community wealth building?

Illustration by Zoran Svilar

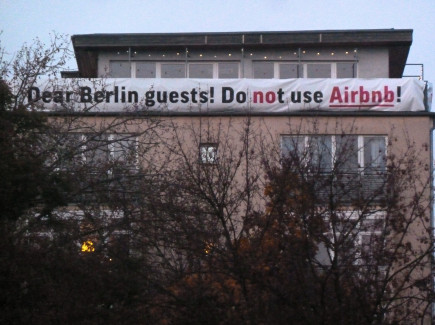

The most influential real estate company in history does not own much real estate. It has made housing less affordable, created housing crises in popular tourist destinations, hollowed out communities, and reached a valuation of $113 billion – all without owning the physical property.

Yet Airbnb has a great deal of property. What the company lacks in physical property it makes up for in intellectual property (IP), the legal and economic codes that govern creativity, information, brand, and reputation in the global economy. If you are one of Airbnb’s half a billion users, when you browse listings, make a booking, pay, or contact customer support, you are interfacing with diverse types of IP, such as copyright-protected software code, trade secret-protected algorithms, and hundreds of the company’s patents. As Airbnb expands into new markets, it explains to its investors that the company’s long-term growth will come from the web of IP that surrounds the rental and housing market.

Airbnb’s intangible empire is far from unique. Physical property, commodities, resources, products – things you can touch – are increasingly marginal in market value. The shift has been seismic: 50 years ago, 80% of the value of the world’s largest companies was in hard assets; now 90% is in intangibles. And the shock waves keep coming. The value of intangibles has increased tenfold in the last seven years, to $65 trillion, or more than 75% of the global economy. No global supply chain, no trade agreement exists without intellectual property running through it. Digital power would not be possible without it.

We cannot understand digital capitalism today, and its many inequities, without understanding how it has transformed every act of the human imagination, every data point, past and present, into a potential commodity. A new generation of ‘disruptive’ tech firms have found ways to use IP as an important part of their arsenal to control and exploit the labour and data of digital workers and consumers alike in the so-called sharing economy.

Yet perhaps no other asset class is as ripe for revolution. For all its power in the economy, IP is also uniquely vulnerable. We can occupy the vulnerabilities of the current system, untether creativity and data from exclusion and personal possession, and forge it instead as a radically imaginative, generative, and socially productive community-building practice.

screenpunk/Flickr/(CC BY-NC 2.0)

Abolitionist creativity

Today, trillions of imaginary dollars are exchanged for rights to imaginary property, yet we lack the imagination necessary to transform the economy into something that could help life flourish. Now, more than ever, creativity is the way out of the deadlocks we face. But for it to thrive we must first abolish the economic and legal codes that shackle it.

Abolition is about presence, not absence. It’s about building life-affirming institutions.

Creativity enters the economy as intellectual property, the legal regime arising from seventeenth-century Europe, which formalised creative expression and invention into individual exclusive rights. As a catch-all term for copyright, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, intellectual property is everywhere. The technology of the smartphone you may be using to read this could have as many as 250,000 related patents. The report of which this essay is chapter carries a copyright notice – in the form of a Creative Commons license – on the first page. Even the scribble you may have doodled on a napkin is automatically copyright-protected, whether or not you want it to be (and irrespective of its aesthetic prowess).

Copyright law does not care whether what we have created is any good from an artistic perspective. For work to be protected by copyright, it must be ‘original’ and ‘creative’, but the threshold is very low: slightly more creative and original than organising a telephone directory in alphabetical order.

Founded on concepts of labour and individualism developed by Enlightenment philosophers, IP was imposed throughout the globe through European colonial and settler-colonial projects and trade agreements. To this day, the IP system remains rigidly Euro-centric with no agreed means to recognise and respect non-European epistemologies or conceptions of the individual.

The regime is fortified by powerful and legally vindictive institutions whose jurisdiction extends to all members of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Under the banner of policing ‘IP infringement’, IP laws can block any good at the border and preclude even the most essential innovations from being made available to the public. And its power seems to only expand. Under pressure from a wide array of corporate lobbyists, exclusive rights that at one time elapsed have become perpetual and expansive, eroding the public domain.

Naturally, such a system inspires resistance. Critical voices resist the colonial capitalist worldview of property rights that undergirds the system. Pirates and free-culture advocates insist that ‘information wants to be free’, establishing alternative platforms for sharing culture. Even liberal defenders of IP regimes grudgingly admit that while the initial set-up was wise – it would promote ‘the ideal of progress, a transparent marketplace, easy and cheap access to information, decentralized and iconoclastic cultural production, self-correcting innovation policy’– the system has been corrupted by corporate influence, undermining a culture of sharing and remixing.

What is to be done? Eliminate IP altogether? Reform it through public policy? Develop legal technologies that allow creators to opt out? Champion online piracy and infringement campaigns? Though these debates are important (some more than others), they dangerously curb our imagination. By limiting our gaze to the inner world of what constitutes IP – whether and how creative works should be protected, what should be considered intellectual property – we are failing to do the radical work: to locate IP in the broader political economy, to question what role it plays in the larger structures of exploitation and oppression.

When we move away from the culture wars that have dominated debates on intellectual property itself, we are forced to contend more seriously with the materiality of creativity – with how it runs through every global supply chain and every international trade agreement one can think of, with how it makes digital power possible and pervasive. Capitalism recognises this power and moves to tighten its grip. Headline-grabbing capitalist cowboys like Jeff Bezos, Nathan Myhrvold, and Martin Shkreli, are innovating around the incongruities of this powerful asset class. Anti-capitalists have been asleep at the wheel.

The inattention is not surprising. The mention of intellectual property can cause even the brightest eyes to glaze over. It is one of many issues deliberately made to seem abstruse, overly technical, legalistic, and irrelevant for the crises we face. One should not need a law degree to understand the terms upon which their creativity enters the economy. Freeing IP from its legalistic scaffolding, and waking up to its power, reveals that it is a uniquely vulnerable regime.

Here is the vital loophole: crucially, ownership and control of IP always belongs, in the first instance, to the artists, inventors, academics and creators who made it. Currently, this power lies dormant. Most IP producers uncompromisingly surrender their IP to corporations (both for profit and not-for-profit) through employment contracts, click-wrap terms and conditions, and IP licences that allow these institutions free rein to commercialise the IP in exploitative and oppressive supply chains. Others simply give their power away by using Creative Commons or Open-Source licences, but again do nothing to stop corporations from then aggressively and oppressively commercialising IP.

Could we imagine a different way? What if creators seized their IP rights, occupied them, and turned their logic on its head? What if we took the essence of IP – the economic and legal right to exclude others from an intangible – and opted to exclude only oppression and exploitation? Can we leverage our legal rights as creators to throw a spanner in the works of capitalism? What if creators did not simply protest the regimes that incarcerate the imagination but created, here and now, the grassroots systems, structures, and institutions to replace them?

Towards these ends, we are not primarily concerned with the abstract question of whether intellectual property should exist. Abolitionist creativity for us is not about eliminating the rights of creators or the protections afforded to creations; it is about ensuring that creativity enters the economy as a tool against oppression. In the words of the abolitionist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore, ‘Abolition is about presence, not absence’. We ask creators to show up and be present in the rights we have been afforded, to occupy them, and to put them together in service of the worlds we want to create. To use our creativity to build life-affirming institutions.

Inspired by the questions offered by abolitionists Mariame Kaba and Dean Spade in their thinking on ‘non-reformist reforms’ (the term originally coined by French economist-philosopher André Gorz in the 1960s), we ask creators to ask themselves: What is the purpose of creativity, of information, of knowledge? Does it provide material relief to the oppressed and exploited inside the supply chains within which the creativity is commercialised? Does it build power, mobilising ongoing struggle among those affected by the creative works? Does it leave out marginalised groups? Does it legitimise the system?

The abolitionist gaze sees creativity, as rendered in our economy, as a thread that weaves through interlocking systems of oppression. It invites us to pull that thread.

The global IP regime is vulnerable for another reason, too. Precisely because it is awkwardly modelled on Early Modern laws related to physical property, IP is full of contradictions and absurdities, which offer intriguing opportunities for transgressive experimentation, radical imagination, and subversive play. Here are a few.

Plots from the abolitionist future

Plot #1: Protest as copyrighted performance

Protest is increasingly criminalised across democracies. During peaceful rallies against climate inaction, racial injustice, police brutality, or war, security services arrest and violently repress protesters, journalists, and human rights monitors. Police commanders send out orders to ‘take back the streets’, transforming individuals exercising a fundamental democratic right – the right to protest – into criminals. More countries are introducing laws to hold protesters criminally and civilly responsible for property damage that occurs during protests.

Digitalisation has become a crucial component of states’ enhanced surveillance and coercive capacity, and they deploy it with little regulation or transparency. Journalists, civil rights advocates, and protesters have documented government use of surveillance, social media monitoring, and other digital tools – warning that it could take years after a protest to learn all of the ways that security forces surveilled organisers. Governments are also coordinating with tech-savvy private security forces who got their start as contractors in the ‘war on terror’. The ‘overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social, and political problems’ is what abolitionists refer to as the prison-industrial complex.

Leslie Peterson/Flickr/(CC BY-NC 2.0)

During the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock, for example, leaked documents exposed that state and federal military forces were working alongside a private military contractor, TigerSwan, hired by owners of the pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners. Working with police in at least five states to attack the Indigenous-led movement Water Protector, TigerSwan was using military-style counterterrorism measures and digital surveillance to monitor protesters’ movements, including a live video feed from a private Dakota Access security helicopter.

Here is where intellectual property comes in. What if we legally protect the creativity inherent in protest as copyrightable performance art? Protests routinely incorporate performative innovations into their repertoire, from Standing Rock to Mexico to Iraq to the United Kingdom. We know that for communities in resistance, ‘the rituals, dances, protocols and songs that characterise these struggles are not merely the cultural ephemera of activism; they are an intimate and constitutive part of Indigenous world-making, a means to coordinate and align the collective imagination so as to facilitate and enrich the cooperation of those involved’. Scholars have long recognised the performativity of protest, studying the use of visualisation and space or arguing that ‘choreography, movement and gesture are not peripheral but central to the politics of protest’. What if protestors acknowledge that these key features of protest also have legal rights that can help them challenge the prison-industrial complex?

Imagine if protestors wore the © ‘all rights reserved’ on their bodies or adorned themselves in barcodes that linked to their copyright terms and conditions, specifying that images and audio could not be used for commercial use, including privately contracted surveillance. Imagine if protesters then demanded in court to know how private security forces were using any recording of their art, visual or audio? Imagine if legal discovery (the pre-trial procedure in which each party can obtain evidence from the other party through requests for documents) then revealed the secret commercial interests between police departments and private security companies, or between a private mercenary firm and its employer, an oil company. Imagine if these companies then had to compensate protesters for copyright violation, or if courts threw out evidence because companies had obtained it unlawfully with copyright infringement. Copyright law is not going to get protestors out of jail for criminal charges, but it can help to ensure that the prison-industrial complex cannot profit from policing.

How would the creators of a copyright-protected performance by Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter, BP or not BP, #NoDAPL, and countless other fearless activists want to condition the use of their performance? What kinds of legally enforceable exclusions would further the goals of their direct action or community response? Should protestors allow police departments (and the private security companies they increasingly work with) to use video and sound recordings of a scripted performance (i.e. a protest) or of visual art such as graffiti – and any other copyrightable material – without any conditions? What should anyone who seizes or destroys an encampment-as-art installation have to pay in reparations?

We inhabit systems that afford more legal protection to performing outrage at injustice than to claiming justice as a right; systems that value the sanctity of property more than the sanctity of Black and Indigenous lives, more than protecting biodiversity. There is no reliably enforceable international human rights regime, but there is a powerful international legal regime associated with intellectual property. We can radically repurpose this power. We can jailbreak the codes and the legal technology of IP from its intended use.

The possibilities are intriguing. Might we be better able to occupy physical property by occupying intellectual property, refashioning the absurd powers given to intangible property into furthering our ability to hold physical space? Can copyright protection complicate how digital power increasingly oppresses protest or acts of preservation, whether they be about environmental issues or dignified living?

Anyone can participate. Every protestor is a performance artist. For those who already identify as socially engaged artists or artivists, here is an opportunity to rethink the political agency of your art. Can a work of art have direct political agency, not through debates over the righteousness of its political aesthetic or content, but through artists occupying the legal and economic scaffolding that surround it?

Plot#2: Occupy employment contracts with IP morals clauses

Employment contracts are where we, as IP producers, most often hand over our rights. We cede to corporations what legally belongs to us through the IP assignment clause: a contract term that gives our employers full ownership and control to use and commercialise our IP. Given the enormous value of IP to a corporation’s bottom line, it is no surprise that corporations have tried to make their claims to employee creativity as broad as possible.

Laws governing employee IP assignment clauses vary by jurisdiction, but common terms require employees to relinquish all moral rights: legal rights that empower creators to object to uses of their work that harm their honour or reputation. Other common terms grant employers ownership of any idea recorded on any piece of corporate property, including an employee’s idea for a personal project if they happened to record it on a work laptop.

What would happen if we occupied our IP assignment clauses? What if we organised collectively as IP producers and put conditions on our employers’ rights to our IP? One existing legal technology we can use is the morals clause: a contractual term that gives one the right to terminate a contract, or take other remedial action, if the breaching party engages in immoral behaviour. What might co-created abolitionist IP morals clauses stipulate?

What if our employers were no longer able to use our IP in supply chains with forced labour and ecological devastation, or in service to militaries, surveillance, and policing?

IP has tremendous power to disrupt an entire supply chain. An IP dispute has the power to stop goods at the border. If IP producers in one part of the supply chain were to use morals clauses, they could trigger an IP dispute whenever these morals are infringed anywhere across a supply chain in which the IP is used.

Here is an example from Big Tech, whose supply chains have insatiable appetites for cobalt. Cobalt mining is notorious for its human rights abuses, corruption, environmental destruction, and child labour. An IP morals clause used by IP producers across these supply chains – say by the Tech Workers Coalition – could be used to implement proposals made by human rights activists, that ‘any company sourcing cobalt from DRC must establish an independent, third-party system of verification that all mineral supply chains are cleansed of exploitation, cruelty, slavery, and child labour. They must invest whatever is needed to ensure decent pay, safe and dignified working conditions, healthcare, education and general wellbeing of the people whose cheap labour they rely on’. If such conditions were embedded into an IP morals clause – capable of crippling cobalt-dependent supply chains by triggering an IP dispute when violated – the entire market power of IP could be used as a carrot and a stick to implement such proposals.

Academics, journalists, artists, and musicians can wield powerful IP morals clauses, too. Publishers depend on paper, ink, and glue, or computers, software, Google, and Amazon to disseminate their copyright-protected works. However, the ‘pulp and paper’ industry continues to profit from deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, ink manufacturers violate labour rights and dump hazardous waste, and book bindings are not recyclable. Digital publishing, meanwhile, fuels supply chains that routinely dump electronics waste across the Global South. Copyright producers can use IP morals clauses to condition the publication and commercialisation of their works on a publisher’s commitment to use state-of-the-art, labour-and-environmental-friendly supply chains. Such conditions can exist alongside open-access licensing terms that enable anyone to freely access copyrighted content, while still prohibiting publishers from delivering open-access content through unethical supply chains.

Through IP morals clauses, can we put ideas about abolition, sustainability, or human rights into practice across the supply chains in which these ideas are commercialised. We can also harness the power of IP to deepen worker solidarity across supply chains. In the process, we can experiment with IP not as an exclusive individual right but as a collective tool. Can we imagine IP unions organised around collective IP morals?

Why open access is not abolitionist

Abolitionist creativity can be at odds with the IP world’s most successful countercultural movements, such as the free software movement, the open-source movement, and the Creative Commons movement. Although heterogeneous, and engaged in spirited debates among each other, these movements share a common concern: how does society resolve the mismatch between what digital technology theoretically enables – the opportunity to access, share, and collaborate on creativity at an unprecedented scale and with near-zero marginal cost – and what copyright law restricts?

The answers of open-access movements have succeeded in building an alternative community, culture, and practice in relation to copyright. Through creative messaging and accessible educational resources, these movements have brought copyright into the public sphere and freed it from its arcane scaffolding. Their easy-to-use standard licences allow creators to opt out of the default ‘all rights reserved’ framework and exercise greater agency without needing to become experts in copyright law. The movements have also made information more accessible to those who cannot afford paywalls, and enabled collective action to create more secure, privacy-conscious software.

Abolitionist creativity builds on the contributions of contemporary open-access movements, but fundamentally shifts the crux of the problem. Open-access movements are centrally concerned with how to share ideas and culture more freely; how to facilitate free speech and free access while sustaining innovation. These concerns are a product of the location and historical moment from which they emerged. In the 1990s, computer scientists and cyberlaw scholars in Europe and the United States who participated in the rise of software and the internet as mass tools (the so-called Information Age) sought to resolve a particular challenge: how to realise the potential and hope of the internet while copyright law grows increasingly restrictive and punitive.

Instead, we begin our analysis by looking at the broader global system in which knowledge and information operate: a settler-colonial system that extracts wealth, knowledge, and culture from economically marginalised communities and inequitably redistributes their economic fruits to the wealthiest and most powerful. This approach is in line with critiques that activists and critical scholars have long made of open-access movements: that the central focus on liberty values ignores concerns about equality; that a romantic notion of the ‘public domain’ as a neutral landscape where every person can reap its riches ignores its real role in exploiting the labour and bodies of people of colour, women, people from the Global South, and the impoverished. We now know that the ‘public domaining’ of Indigenous knowledge about local flora and fauna, traditional medicines, folklore, or traditional cultural expressions has enabled Big Pharma to take Indigenous knowledge, transform it into IP, and become the exclusive owner of that knowledge: a phenomenon known as biopiracy.

Abolitionist creativity also disagrees with an ideological belief that runs through some prominent segments of the open-access movements, namely that the system once worked well, but that ‘unfortunately, our IP regimes have strayed far from their original purposes’. For the colonised, for Indigenous Peoples whose collective knowledge has been ransacked, for communities forced into oppressive trade agreements (e.g. TRIPS), for the rising number of modern slaves working in global supply chains powered by intangibles, it is hard to see how the IP system ever worked for them – or what decades of reformist attempts inside IP law in the US have accomplished. For abolitionists, the system is not broken and in need of reform, tweaking, and tinkering. It is working as it was designed to work, as a settler-colonial legal and economic structure. And we are running out of time and of magical thinking waiting for public policy to somehow turn favourable in a corporate-dominated oligarchy.

Open-access movements must also confront an uncomfortable fact: Big Tech is on their side. The conventional wisdom that large corporations always prefer stronger IP regimes to block new competitors, or that zealous enforcement of IP law favours the powerful, is not borne out by the historical record. With the exception of the pharmaceutical industry, monopolists in technology-intensive industries have resisted strong patent protection throughout history: the railway industry in the nineteenth century, IBM in the computing industry of the 1960s and 1970s, Big Tech today. Google, Facebook (Meta), and Twitter are trying to selectively apply IP enforcement, spending millions of dollars lobbying to ensure as little IP friction as possible inside markets in which they already have dominant market power, to have unfettered control over data and knowledge, to continue to make ‘colossal advertising profits from content produced for free by users’, and to avoid the dreaded IP dispute.

If the most powerful actors are the real winners in an open-access world, shouldn’t we re-evaluate the claim that ‘information wants to be free’? If free access means continuing to ignore the pleas of Indigenous communities to stop the biopiracy, cultural expropriation, and ‘public domaining’ of the colonised, why do we continue to hold it as an absolute value?

Unlike open-access movements, abolitionist creativity recognises that the global economy into which we release our creativity is not a neutral, level playing field. Surrendering or limiting the existing rights to creativity in our current system does nothing to interfere in the structure of oppression. It simply cedes agency to more powerful actors – agency that should be ceded down, not up. Rather than relinquish our rights on behalf of a kind of libertarianism for the Information Age, we should open our eyes to the material ways our creativity enters the economy and reifies structures of digital (and other types of) power.

As our plots for an abolitionist future illustrate, there are intriguing experiments and exercises in recognising and repurposing the power of what is classified as ‘intellectual property’. By seizing the means of imaginative production, we can transform creativity into a tool for collective liberation that disrupts and overturns the very regimes of digital power that enclose and exploit it. At the same time, far from reifying the IP system itself, abolitionist creativity highlights its contradictions, shakes its equilibrium, and creates internal crisis. If there is a future for intellectual property, we will discover it, collectively, in our acts of resistance and imagination.