Window of opportunity for public water in Catalonia

Regiones

The water management situation in the region of Catalonia, Spain is catastrophic. The omnipresence of the private water sector is creating hugely negative impacts at the economic, social and environmental levels. As a result, Catalan municipalities are being swept by the wave of water remunicipalisation that is taking place across the globe, and the drive to recover public management of water systems is gaining force.

Enginyeria Sense Fronteres Catalonia

Enginyeria Sense Fronteres Catalonia

The Catalan quasi-monopoly in water

The privatisation of water services today affects roughly 84% of the population of Catalonia, through either mixed corporations or fully private companies. This situation is quite unique given that, to the contrary, the great majority of water systems are under public control globally. Furthermore, the region’s water management landscape has two distinctive characteristics.

First, private companies are concentrated in medium-sized and large population centres. Although more than half of Catalan municipalities have public water services (507 compared to 437 where these services are privatised), they only represent 16% of the population. We are therefore talking about small municipalities, where it is hard to benefit from economies of scale and where the return on investments is lower than in the bigger cities where private companies can expect to make profits.

Second, a handful of companies share the water market. For example, 90% of municipalities with private water management are served by companies from the Aigües de Barcelona group that operates in 24 countries – also known as AGBAR and a subsidiary of the French water multinational Suez. Under the AGBAR umbrella we find companies such as the Societat General d’Aigües de Barcelona (SGAB), SOREA, CASSA, Aigües de Catalunya, Mina Pública de Terrassa, Aigües de Girona, Aigües de Tarragona and many more. It is worth noting that AGBAR has managed water in the city of Barcelona since 1867, with the latest change taking place in 2012 when a mixed company was created, under 85% private and 15% public control.

Paying more for lower quality services

One of the first conclusions we reach when analysing the different models of water management in our territory is that private services are more expensive than public delivery. Specifically, according to the Spanish Court of Auditors, water is 22% more expensive for small and medium-sized populations if they have a privatised service, with the aggravating factor that with private management, leakages in the network are 30% greater and investment is 15.5% less than in the public sector. In the big cities it is evaluated that private water management can be 25% more costly.

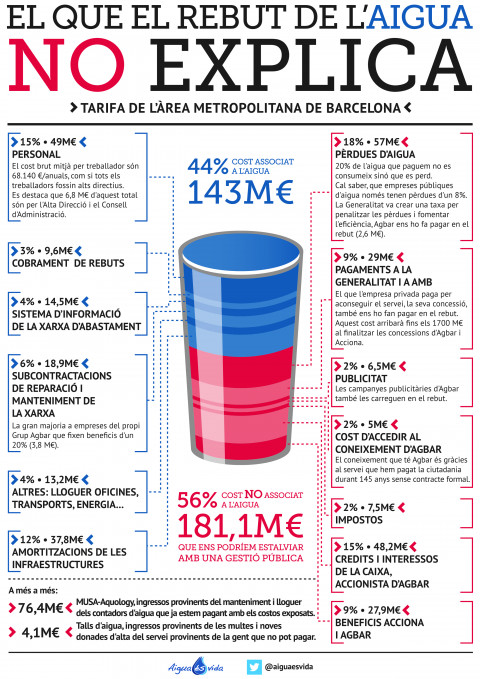

This price differential can be explained by the inclusion in the water bill of costs not associated with the service: a careful analysis of the tariffs paid by the citizens of Barcelona highlighted that they allowed for a profit margin but also included, among other things, the costs of advertising, fines associated with low performance (losses and leakages), high levies and fees charged by the administrations in exchange for privatising the service, exorbitant salaries for the administrative councils, financial spending not associated with water delivery and so on. To the extent that more than half of the water bill in Barcelona today is comprised of unnecessary or illegitimate costs not related to water services per se. In fact, if we compare the water tariffs in Barcelona with the closest municipalities that have public management, they are 91.7% more expensive.

Just as, economically speaking, private water management is bad policy (except for the few shareholders who reap up the profits), socially, its impact is also very controversial.

One reality that has become starker in recent years is that of families whose water supply is cut off because they cannot pay the bills. In 2010 the UN General Assembly recognised access to water and sanitation as a fundamental human right. Subordinating this right to a person’s ability to pay is a flagrant violation that stigmatises thousands living in already precarious conditions. It is evaluated that in Catalonia in 2014, 120,000 people (1.6% of the population) were deprived of running water in their homes because they could not cover the water bill. These cases of water cut-offs mostly occur where water services are privately managed: 75% of municipalities with private services cut off water supplies for unpaid bills, whereas in the municipalities where the service is public that proportion falls to only 8%. These diverging approaches demonstrate very different interests and priorities.

Remunicipalisation calling

It is no surprise, given such poor results, that municipalities are beginning to defy the prevailing logic and to consider the option of remunicipalising water services.

In accordance with what is happening in the rest of Spain, Europe and the world, the remunicipalisation of water services is a tendency that is clearly on the rise in Catalonia, both demonstrated by past experiences and current ones. Perhaps more importantly, service delivery is now a matter of public debate, whereas it was previously treated as a technical question. At the time of writing, nine Catalan municipalities have returned their water services to public management after privatisation experiences. Six of these cases took place in 2014.

It is predicted that this wave will continue to gain strength in the coming years for several reasons: on the one hand, the recent municipal elections have brought numerous political forces into government with a clear commitment to public water management; on the other hand, the pressure is rising from a social alliance in favour of this option and it is finding a voice despite the media’s silence on the issue. Finally, in the years to come, privatised service contracts are coming to an end in many municipalities and they will have to decide whether to open a new tender for private management or to take the service back into public hands.

Table 1. List of municipalities which private service contracts will end between 2015 and 2019 in Catalonia

|

Municipality |

Population |

Year the concession ends |

|

Massanes |

708 |

2015 |

|

Balenyà |

3,728 |

2016 |

|

Brunyola |

393 |

2016 |

|

Folgueroles |

2,249 |

2016 |

|

Llers |

1,229 |

2016 |

|

Mieres |

337 |

2016 |

|

Parets del Vallès |

18,580 |

2016 |

|

Pont de Molins |

540 |

2016 |

|

Ripollet |

37,234 |

2016 |

|

Sant Julià de Vilatorta |

3,076 |

2016 |

|

Terrassa |

215,055 |

2016 |

|

Aiguafreda |

2,502 |

2017 |

|

Castellfollit de Riubregós |

183 |

2017 |

|

Navata |

1,258 |

2017 |

|

Sant Cugat del Vallès |

87,118 |

2017 |

|

Sant Vicenç de Torelló |

2,013 |

2017 |

|

Santa Eugènia de Berga |

2,244 |

2017 |

|

Alpens |

304 |

2018 |

|

Muntanyola |

585 |

2018 |

|

Sant Llorenç d'Hortons |

2,535 |

2018 |

|

Torelló |

13,908 |

2018 |

|

Bescanó |

4,839 |

2019 |

|

La Pobla de Massaluca |

372 |

2019 |

|

Oliola |

230 |

2019 |

|

Riudaura |

452 |

2019 |

|

Sant Carles de la Ràpita |

15,245 |

2019 |

|

Santa Cecília de Voltregà |

179 |

2019 |

|

Santa Eulàlia de Riuprimer |

1,231 |

201 |

To the arguments feeding the wave of remunicipalisation we must add two more variables:

The acquisition of new data about management: In Catalonia we are suffering the consequences of a long tradition of private water management. Among other things, that means that information is glaringly absent and that the existing regulatory body does not play a substantive role. Because of this lack of control over the water sector, municipal administrations cannot give precise answers to questions such as how many people have had their water cut off for non-payment, what is the status of investments made by the private sector or when concessions will end. This explains why the data presented in Table 1 remains incomplete, having been obtained from civil society actors fighting for public, non-commercial and democratic control of water supplies. At the Catalan platform Aigua és Vida (Water is Life), we only have information about roughly 20% of the privatised areas. This situation poses a major challenge for proponents of remunicipalisation because the current situation places the private sector, and most notably AGBAR, at an advantage in terms of planning and strategy to secure new contracts in each of these municipalities.

Cancellation of existing contracts: In cases where there are unfulfilled commitments by the private sector and irregularities in the privatisation process itself, the termination of contracts before the final date is more likely. The municipality of Alfés, for example, decided to cancel the private contract and take its water services back under public control due to the lack of justification provided by the company for the rates it was charging despite poor quality service. Control of the water service in Santa Maria de Palautordera was also taken back by the municipality when it was shown that the poor state of the network was due to poor maintenance. In El Vendrell and La Bisbal d’Empordà there are legal processes under way associated with the tenders for privatisation and related failures to meet contractual obligations. A municipal investigation committee is also bringing to light the extent of the disarray and possible cases of corruption linked to the management of water services in Girona.

The situation in the Barcelona metropolitan area deserves a specific mention: after AGBAR provided services without any form of contract for decades (a situation described in 2010 by a judge as “illegitimate actions” and “illegal rates”), a new public-private company was created in 2012 and AGBAR was invited to form part of it, without public tender. There was an aberrant valuation of the shares that clearly favoured private interests, and the concession period was extended until 2047. This manoeuvre is currently being studied by the Spanish tribunals and the European Commission, as well as numerous other public bodies (e.g. Oficina Antifrau de Catalunya and Autoritat Catalana de la Competència).

It is therefore to be expected that remunicipalisation processes will not only come about as a result of the natural termination of contracts, but also because of their premature conclusion.

Setting precedents

Without a doubt, the case of remunicipalisation in Arenys de Munt illustrates a broad range of key considerations related to recovering control of our water services.

In Arenys de Munt the service was privatised and had been in the hands of SOREA – of the AGBAR group – since 1999, with a contract that ended in 2010. The Local Council demanded that SOREA provide information about the state of the concession at the close of the contract, and the company responded that there were pending debts in the order of €700,000, which is practically the annual budget for water services and a considerable sum for a municipality that has an overall budget of approximately €7 million.

After considering the possibility of creating a mixed company, the council decided to take full control of water management through a public company. The reaction of SOREA was clear: it took the case to the tribunals, calling for the liquidation of the debts and compensation for loss of income. The private company also tried to get the workers on its side in a court case that it ultimately lost. An external audit revealed that nothing was owed to SOREA, and that in fact they had violated the clauses of the contract in the termination process. It was also discovered that SOREA had inflated the cost of services and subcontracts, with some budgets multiplying the real market value fourfold.

Within this scenario, the transition from a privatised to a public service was very complicated. It was in the first few months of municipal management that the network’s real level of water production inefficiency (net production of water against consumption) of SOREA was discovered: it was only at 57 per cent although it was supposed to have increased to 75 per cent. Nevertheless, during the first four years of the remunicipalisation Arenys de Munt was able to increase performance up to 67%, to implement progressive rates with a social block and to manage water services as a common good and not a commodity, as had previously been the case.

Opportunities multiply

The obstinacy of SOREA and its attempt to obstruct the remunicipalisation of water services in Arenys de Munt – a town with 8,654 inhabitants – is telling. The company is afraid of these pioneering cases of return to public water lest they become precedents to be followed by other municipalities creating a snowball effect. Despite SOREA’s efforts, the arguments in favour of remunicipalisation have only grown more and more solid, and many towns are now following in the footsteps of Arenys de Munt.

The municipality of Figaró-Montmany was another pioneer in the remunicipalisation of water services in 2010. This experience was very similar to that of Arenys de Munt: legal processes, petitions for high compensations, which external auditors have called into question, and the infrastructure in a very poor state. The private company refused to release critical operational information to the new public utility or local government – e.g. proprietary software used to manage billing, water meter data collection, and monitoring maintenance works. Clearing hurdles, the town’s council decided to open up the debate about what type of public water management local residents want.

Under the austerity pressure, Catalonia Government owned regional company Aigües Ter-Llobregat (ATLL) was sold to private company in 2012. ATLL extracts water from rivers and aquifers and supplies to the municipal reservoirs. Municipal or private operators then supply water users. Privatisation of ATLL led to a sudden 83% increase in the price that various town councils paid to the company. This was sufficient motive for the Local Council of Vilalba Sasserra to remunicipalise the service in 2014 to offset this extra charge by eliminating the unnecessary costs charged by the private operator SOREA – of the AGBAR group; in that way, the Council avoided passing on the ATLL’s increase in bulk water supply costs on to the citizens.

In the case of Montornès del Vallès, the remunicipalisation came in 2014, following 50 years of private management. The complete lack of transparency and the deficient maintenance of the infrastructure were among the motives that led to this decision. Achieving greater transparency and improving performance of the water system are the key aims of the new public management team.

The next steps

The historic and dominant presence of private companies in Catalonia’s water management combined with the privatisations of recent decades has granted them a quasi-monopoly on service delivery in the region. One of the most serious consequences – and the most difficult to evaluate – is the dismantling of public structures and the loss of the accumulated public capital.

Today we find ourselves in a situation in which the majority of waterworks professionals are employed by a single multinational, which has also reached agreements with universities for training, meaning that teaching is based on the company-client paradigm that is far remote from the concept of common goods. In the legal and judicial sphere there is also a long way to go, starting with undoing the agreement that the AGBAR Foundation reached with the General Council of the Judiciary to literally “train judges on issues of water law.”

It is therefore crucial to understand that remunicipalisation of water services cannot be limited to administrative changes in the way water services are provided in a given municipality. Real change can only come from democratisation and citizens taking ownership of these services; it is also necessary to build a broader understanding of the concept of such services as common goods, in education, in courts, in the media or in politics. The remunicipalisation of water services is just one piece of the puzzle in a society challenging the commercialisation of life and opting for putting people and the environment first.

Eloi Badia and Moisès Subirana collaborate with Enginyeria Sense Fronteres Catalonia (Engineers without Borders). Both of the authors are also members of the Catalan platform Aigua és Vida (Water is Life), which brings together organisations and individuals in order to achieve public, democratic and non-commercial management of water services.

This article was written for Un futur per l'aigua pública: L'experiència mundial de la remunicipalització published in September 2015 (Catalan edition of Our Public Water Future: The global experience with remunicipalisation, published in April 2015) and translated into English.