Portuguese elections: All (not so) quiet on the Western Front

Regiones

On 4 October, Portuguese and international news outlets reported a win for the right-wing coalition as a victory for austerity policies. But the latest news shows that a left-wing coalition government may yet emerge, reflecting growing popular anger and resistance to unemployment, poverty and corruption.

Pedro Ribeiro Simões https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosimoes7/

The day after the election the narrative of the media was clear. Portuguese voters were not opposed to austerity and had voted for a neoliberal government for yet another four years. Progressive parties were reported to be in disarray. A more nuanced reading of electoral results – and the ensuing media campaign against a now viable left-wing agreement – shows how skewed against progressive solutions the mainstream commentariat actually is.

Austerity, Portuguese-style

For the better part of the last 15 years, people living in Portugal have faced stagnation. Economic and social decline accelerated after 2009, as initial austerity measures were enforced by the minority government led by then Prime-Minister José Sócrates. In 2011, as the first Memorandum was signed with the Troika (the European Commission, European Central Bank and the IMF), austerity took a harsher turn. A broad privatisation programme was accelerated and welfare cutbacks were enforced. Youth unemployment mounted on the back of increasing precarization.

It is important to note though that Portuguese-style austerity was less harsh than its Greek counterpart. Partly because of how Portuguese society and state structures work, and partly because of the way austerity was applied to specific sectors such as health, austerity policies were less intense and all-encompassing as the experience in Greece – even if the actual burden for people was still significant. Out of pocket private payments for public healthcare for example now make up 30 per cent of total healthcare expenditure.

Together these measures had their human toll. Emigration from the country surged, similar to rates in the 1960s, as a large swathe of mainly young people went to France and Germany. There are no definite statistics on outward migration flows, but estimates point to half a million individuals leaving the country since 2011. Most are highly-skilled individuals educated through the public education system. Child and elderly poverty rates increased as a result of cutbacks, since welfare transfers are often the only safety net in Portugal for at-risk social groups. The incumbent government refuses, to this day, to admit guilt or responsibility for these consequences. The country is now poorer and increasingly divergent economically from its EU partners.

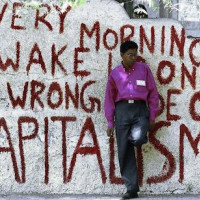

People living in Portugal have not reacted passively to these developments. Demonstrations across the country on 12 March 2011 tore into the national consensus on austerity and forced Portuguese society to face up to the scourges of labour precarity, youth unemployment and the end of collective bargaining. On 15 September 2012, the largest demonstrations in a generation took place throughout the country.

A number of general strikes were also called by CGTP-IN, the largest trade union confederation, however unions have definitely become weaker social and political actors due to economic transformations, as the Portuguese economy is now service-based and predicated on a low-wage, job-insecure model. Moreover, unions have failed to adapt to new work environments nor responded effectively to demands by younger workers. With neoliberal policy entrenched, unions have faced constant attacks by business interests embedded in the Portuguese state apparatus.

New political actors and formations have emerged though, including alliances that ran for Parliament in 2015: LIVRE/Tempo de Avançar, Nós, Cidadãos and AGIR, among others. This has been matched by the growth of self-organized initiatives in urban centres. In this context, a right-wing win in the 4October election seemed both astonishing and disheartening.

Election stalemate

However the supposed right-wing victory was not so clearcut. There was no real electoral gain for the incumbent government coalition which brings together Partido Social Democrata (PSD), and Centro Democrático e Social – Partido Popular (CDS-PP). The former is led by Pedro Passos Coelho, a liberal technocrat, and the latter is run by Paulo Portas, a former journalist who aptly reinvented himself and the party as modern conservatives. Both parties are members of the European Popular Party grouping.

In 2011, these parties ran on independent platforms and agreed to join forces. In 2015, running on a common platform named Portugal à Frente (Portugal Ahead), Passos Coelho and Portas lost up to 820,000 votes. This is significant. Abstention rose – as people are increasingly disaffected from liberal politics and many young voters have emigrated - and some of these votes may have gone over to the left.

Post-election surveys are still to be released, but the most importance consequence is clear. There is no longer an absolute majority in Parliament. Portuguese politics is traditionally majoritarian in the sense that it requires a strong, single-party majority to maintain stability. The lack of an absolute majority in Parliament makes the incoming government’s task more difficult. In itself, this is neither new nor unique to Portugal. But proposed neoliberal policy measures, such as partial social security privatisation and the completion of State enterprise privatisation programmes, will stay on the backburner.

It is unlikely that the government will be able to deepen austerity measures on its own account to the extent it did during the years 2011 to 2015. From now on, all structural reform policy will almost certainly be enforced from Brussels and Frankfurt.

Checks and balances in Portuguese democratic institutions make a stable minority government unlikely. This is why the role of the Partido Socialista, the Socialist Party has become more important than ever.

As the main opposition party, the Portuguese Socialist Party is one of the more centrist social-democratic parties in Europe. It has veered to the right in recent years, making it virtually indistinguishable from the Social-Democrats. In many ways, it is a social-liberal political formation: its MPs support progressive causes, such as same-sex marriage and a modicum of welfare support. But the party subscribes to the European market-driven consensus while fully supporting Europeanism as a core pillar of Portuguese identity.

It is resolutely pro-eurozone and until recently held that “austerity-lite”, a more equitable distribution of cutbacks, was a desirable path towards balanced budgets. It broadly agrees with the Fiscal Treaty regime. Until two weeks ago, it was difficult to establish clear differences between the Social Democrats and the Socialists. Their electoral dominance augmented their political similarity. António Costa, leader of the party, performed poorly in the electoral campaign. Thus, the Socialists were unable to benefit from losses by the right-wing coalition. Instead, their loss was the left-wing’s gain.

The Left Bloc doubled its votes and will form a 19-strong group of representatives in the next Parliament. The Portuguese Communist Party, long held to be in decline and infamously declared the big loser by several news outlets on election night, increased its representation to 17 MPs. There will now be 36 MPs out of 230 to the left of the Socialists in the next government, despite long predictions of a resounding defeat.

Pedro Ribeiro Simões https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosimoes7/

The fearful right

The conservative character of Portuguese society has long been trumpeted by right-wing politicians and pundits. The Portuguese Socialist Party is embedded in this narrative: some of its members prefer stability and grand coalition-style politics. This is why the ongoing negotiations around a left-leaning government, however constrained by EU rules and so-called “international commitments”, have been framed by right-wing pundits as illegitimate, unconstitutional and unstable. The Socialist Party has won 86 seats in Parliament. The Left Bloc has won 19. The Communist Party has won 17. Together, this makes 122 MPs, enough to garner any given government formation the parliamentary support it needs to proceed with its programme and budget.

Even so, any given person living in Portugal would be forgiven for thinking that a left-wing coup was in the works. The reaction has been severe. It does however reflect well-placed fears by the right that a popular front coalition will break the decade-old impasse for the Portuguese left. Indeed, one of the legacies of the 1974-75 Carnation Revolution was a long-standing confrontation between the Socialists and the Communists.

It is too early to assess the potential success of this aggiornamento [coming together after years of conflict], but right-wing pundits have correctly diagnosed its risks and proceeded to engage in misinformation and outright lies. It is certainly true that both the Left Bloc and the Portuguese Communist Party are no Europhiles and hold no sympathy for NATO. But it is also true that both parties are constitutionally entitled to representation and have left their policy preferences on debt restructuring, the euro, the EU and NATO on the side while entering into negotiations with the Socialists, which may eventually result in either acoalition government or a Socialist cabinet supported by Left Bloc and Communist Party MPs .

Both left-wing parties have largely outmanoeuvred their opponents. The Communist Party, in particular, has shown a tactical acumen that has thrown right-wing pundits and parties into disarray. They are no longer able to portray them as obstructive oppositionists. Instead, these actors have relocated the divide: it is now about who stands for the euro, the EU and NATO. This is a rather inept attempt to include the Socialists into a so-called definition of who can legitimately govern, which is basically deemed as all existing parties that have participated in cabinets since 1976.

Cavaco Silva, the President of the Republic, has stated as much. In suggesting that any government must include political parties which agree to membership in the Eurozone, the EU, NATO and a steadfast commitment to all international agreements, including transatlantic partnerships, this significant political actor has sought to exclude both left-wing parties from any viable coalition while putting pressure on the Socialists to silence their criticism of austerity and instead abet the incoming government.

At the time of writing [October 23rd), the President of the Republic, Cavaco Silva, appointed Pedro Passos Coelho as Prime-Minister. The Left Bloc and the Communist Party have already stated their intention to reject the incoming cabinet’s programme and budget in Parliament. António Costa is continuing talks with the Left Bloc and the Communist Party while the right-wing coalition has chosen to break off from talks.

Another election looms

In the end, it all may hinge on the January 2016 presidential election. Pedro Passos Coelho has been appointed Prime-Minister and will face a hostile legislature. It may well vote down both its government programme and its budget proposal. However, the Portuguese President is not allowed to dissolve Parliament in the final few months of office just as the President elect is not allowed to dissolve Parliament in his first 3 months in office.

In his 22 October speech, Cavaco Silva doggedly stood for what he perceives as the only game in town: a grand coalition government which effectively excludes Europeanist critics and Eurosceptics. There was little mention of the Portuguese Constitution or Portuguese democratic institutions in the President’s speech or pundits’ defence of status quo. Instead, there were vague allusions to market appeasement and winner-take-all politics. It is now distinctly possible that, in a few weeks, the President will refuse to appoint a Socialist government supported by the parliamentary left. Thus far, there is little indication that people will take to the street and protest.

The right-wing coalition and its pundits will then seek to blame the left for the ensuing instability. The candidacy of a popular pundit, former MP and Social-Democratic leader Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, has made a conservative President more likely. In that event, the right-wing coalition will play up the blame game and seek an absolute majority.

In conclusion, the 4 October election was hardly a victory for austerity. Instead, it may well have rearranged the Portuguese party system and shed light on the true alignment of Portuguese media outlets, which have been unrelenting in their exclusion of left politics from the horizon of legitimacy. It is now up to movements and trade unions on the left to step up their game and show that these new dynamics of resistance to austerity do not play out only in the party system.