¿Quién lucra con la fiebre de la energía verde? La reducción del riesgo y las relaciones de poder en la financiación de la energía renovable en África

La reducción del riesgo es considerada la panacea para obtener financiación con el fin de expandir la energía renovable en el sur global, pero la experiencia de las asociaciones para una transición energética justa en Senegal y Namibia demuestra que los inversores extranjeros están recibiendo protecciones excesivas contra el riesgo, mientras que los Estados y las comunidades marginadas deben soportar todos los costos financieros, sociales, normativos y a largo plazo.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Los mercados financieros mundiales y el poder estructural de la energía renovable en el continente africano

El volumen de capital que busca inversiones rentables en los mercados financieros ha aumentado considerablemente desde los años ochenta (Huffschmid, 2022). La presión de la rentabilidad en el sector productivo en los países industrializados, la redistribución a favor de grupos sociales que poseen riqueza y el uso de sistemas jubilatorios basados en mercados de capital han contribuido a que ello ocurriera. La creciente amplitud para los actores financieros y la creación de nuevas prácticas financieras provocaron un mayor crecimiento del capital financiero.

Recuadro 1. El poder en las finanzas mundiales Las finanzas mundiales están estructuradas en función de las relaciones de poder. Afectan, por ejemplo, las estructuras y la regulación de los mercados financieros y la distribución desigual de los beneficios y perjuicios financieros. Esto queda de manifiesto en relación con el acceso a fuentes de financiación, la distribución de ganancias y la vulnerabilidad a las crisis. Dado que la globalización financiera surgió como resultado del colonialismo y el capitalismo estructurado por la era (pos)colonial, las economías africanas siguen ocupando una posición subordinada en las relaciones financieras mundiales. Entre otras cosas, esto afecta la devaluación de los tipos de cambio y el modo en que la inestabilidad financiera obliga a los países a reaccionar a la dinámica de los mercados financieros internacionales. Las crisis de la deuda de los años ochenta obligaron a muchos países a aceptar préstamos del Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) y los programas de ajuste estructural conexos. Estos no solo priorizaban el pago de los préstamos del sector privado, sino que además imponían condiciones a los países para que promovieran medidas de liberalización económica y abrieran sus mercados financieros al capital mundial. Como consecuencia de ello, los países están expuestos a relaciones financieras volátiles, en ocasiones denominadas “tsunami de liquidez”. Véase el artículo del TNI sobre financiarización (Dutta y Thomson, 2018). |

Desde los años noventa, se han abierto oportunidades de inversión en nuevos ámbitos como la vivienda o las tecnologías de la información, así como en nuevas partes del mundo. Por consiguiente, muchos países han experimentado tsunamis de liquidez en reiteradas ocasiones,1 es decir, un flujo temporal de inversión, un cambio en las expectativas de rentabilidad de los accionistas y un retiro más o menos repentino del capital (Alami, 2019). Al entrar y salir cuando cambian las expectativas, la financiación de corto plazo en particular aumenta el riesgo de crisis financieras recurrentes. Esta dinámica es ilustrada por la denominada crisis asiática de finales de los años noventa (Bello, 16 de octubre de 2017) o la burbuja “puntocom” a comienzos de los años dos mil. Tras la crisis financiera mundial de 2008, el volumen de liquidez excesiva en busca de ganancias ha aumentado, dado que las tasas de interés fortalecieron al tsunami de liquidez.

En la actualidad, la denominada economía verde, sobre todo el sector de la energía renovable en las economías del sur global, es un destino prometedor para la inversión del capital financiero mundial. A pesar de que es necesario realizar una gran inversión en infraestructura, las vías tecnológicas y las ganancias económicas siguen siendo inciertas y las finanzas privadas perciben riesgos de inversión graves. Como era de esperar, las finanzas privadas intentan trasladar estos riesgos posibles a los gobiernos anfitriones en la forma de apoyo financiero. Aunque la infraestructura pública siempre ha implicado una combinación de financiación pública y privada, la reducción del riesgo intenta reorganizar las economías energéticas, lo que engloba un conjunto específico de instrumentos además de la narrativa que los acompaña. Hasta comienzos de los años dos mil, “la reducción del riesgo de las finanzas” se utilizaba en forma ecléctica para referirse a la externalización de empresas, la microfinanciación o las carteras de fondos de jubilación. Tras la crisis financiera, la reducción del riesgo se volvió un concepto más matizado, centrado en la reestructuración macroeconómica, los riesgos de liquidez y la estabilidad financiera. Cuando el discurso macroeconómico comenzó a incorporar la idea de una “recuperación verde”, ello dio lugar a un debate más específico, centrado en las finanzas verdes y los prometedores aunque riesgosos mercados del sur global. A la propuesta del grupo de estudios E3G durante la cumbre del G20 celebrada en Londres (Mabey, 2009) pronto le siguió una profunda investigación conceptual del Deutsche Bank y del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). El estudio sugería una metodología detallada de reducción del riesgo para políticas de creación de mercados a fin de generar un entorno propicio para las inversiones verdes.

Básicamente, la justificación de la reducción del riesgo es la siguiente: aunque los costos de la energía renovable han disminuido drásticamente, los riesgos percibidos impiden a inversores en países del sur global financiar infraestructura para la energía renovable. A fin de movilizar los fondos adecuados, se necesitan instrumentos de mitigación de los riesgos para que la economía resulte atractiva para la inversión, por ejemplo, al garantizar un flujo de ganancias estable. Estos instrumentos brindan una red de protección para inversores privados basada en un conjunto de medidas, como la evaluación de los riesgos, el seguro de crédito a la exportación, las garantías de inversión, los pagos de primas, los bancos multilaterales de desarrollo como prestamistas de último recurso, la asistencia técnica y la consultoría política, así como iniciativas de regulación nacional para brindar un contexto de políticas seguro y predecible. La reducción del riesgo fue adoptada rápidamente como una estrategia clave para abordar el desafío de financiar infraestructura sostenible. Unos años después de la primera iniciativa política del PNUD, estas ideas pasaron a formar parte del Programa GET-FiT (Elsner et al., 2021), que financia proyectos de energía renovable en Uganda2 y Zambia,3 y en los que se basa el programa de múltiples países Scaling Solar4 del Banco Mundial y el programa RES4Africa5 de Italia, por nombrar algunos.

La reducción del riesgo ahora es omnipresente en la financiación para el clima, ya que figura en numerosas recomendaciones de políticas del Banco Mundial, el FMI o las Naciones Unidas, a saber: “De miles de millones a billones”, “Reconstruir mejor” y “Maximizar el financiamiento para potenciar el desarrollo”, respectivamente. Los proyectos de infraestructura y de energía renovable de gran escala de conformidad con los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible (ODS) y la Agenda 2030 se han vuelto activos invertibles para atraer capital internacional con fines de lucro. La macroeconomista Daniela Gabor se refirió a este fenómeno como el “Consenso de Wall Street”, lo que significa que, a diferencia del anterior Consenso de Washington, la movilización de capital financiero privado ahora se ha vuelto una prioridad política y de desarrollo. En última instancia, este es un enfoque a la financiación para el desarrollo enfáticamente basado en el mercado, centrado en los intereses del capital financiero. Como sugiere Gabor, ello culmina en un “Estado de reducción del riesgo” (Gabor, 2021), cuyas funciones más destacadas ya no son el bienestar y la seguridad humana o territorial, sino la generación de oportunidades de inversión atractivas, moderadas por instituciones favorables a los inversores, cuya estructura se asemeja a quimeras gubernamentales o transnacionales. En el sector de la energía, ello puede incluir subastas de energía facilitadas por consultorías privadas y bufetes de abogados destinadas a inversores de Occidente, como demuestra claramente el caso de Zambia (Elsner et al., 2021).

A continuación, nos centramos en proyectos que demuestran diversos niveles de reducción del riesgo: el caso de las asociaciones para una transición energética justa destaca la reducción del riesgo a un nivel abstracto interestatal, mientras que el caso de Senegal subraya las realidades diarias y el de Namibia ilustra el modo en que podemos transformar toda una economía.

La estrategia de reducción del riesgo de las asociaciones para una transición energética justa

En el contexto de las energías renovables en países africanos, las asociaciones para una transición energética justa (ATEJ) han sido elogiadas como mecanismos innovadores de financiación para el clima. Sin embargo, también ilustran el modo en que se reproducen las relaciones de poder y las desigualdades estructurales mediante la financiación de la energía renovable. Estas asociaciones, que fueron negociadas entre países del G7 y del sur global, intentan catalizar una transición de los combustibles fósiles a la energía renovable.

La primera ATEJ, anunciada en la COP26 de cambio climático en 2021 entre el G7 y Sudáfrica, implica una inversión inicial de 8500 millones de dólares para realizar la transición del carbón a la energía renovable. Financia proyectos para mejorar la red eléctrica, la generación de energía, vehículos eléctricos e hidrógeno verde y pro- pone una transición justa centrada en la creación de empleos y la formación en competencias. Una ATEJ con Senegal, país que aspira a producir gas, firmada en junio de 2023, asigna 2700 millones de dólares para generar un 40 % de energía renovable de aquí a 2030.

A pesar del hecho de que los gobiernos en países ricos ahora estén comenzando a reconocer sus responsabilidades climáticas y estén mejorando sus esfuerzos para brindar financiación para el clima, el modelo de financiación de las ATEJ plantea varias inquietudes. En primer lugar, aunque muchos países del sur global han solicitado financiación para el clima, las ATEJ fueron creadas para servir los intereses geopolíticos de los Estados del G7, que intentan fortalecer su influencia política y económica a nivel mundial, entre otras cosas para responder a la Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta de China. Más concretamente, tan solo una pequeña fracción de financiación llega en la forma de donaciones (3,4 % en Sudáfrica y 6 % en Senegal); el resto adquiere la forma de préstamo en divisa fuerte −que debe pagarse, a pesar de tener tasas de interés por debajo del mercado. Ello expone a los países beneficiarios a riesgos de deuda cuando la divisa local se debilita y los pagos de deuda se vuelven más costosos, como es el caso de Sudáfrica, donde desde 2000 el rand ha perdido 200 % su valor frente al dólar de los Estados Unidos.

Además, el modelo de financiación de las asociaciones se basa en una estrategia de reducción del riesgo. Se utilizan fondos públicos para financiar empresas privadas mediante asociaciones público-privadas. En el sector de la electricidad, que representa la mayor parte de la financiación de las ATEJ en Sudáfrica y Senegal, ello significa invertir en infraestructura para la red eléctrica a fin de crear las condiciones para que empresas de energía privadas, denominadas productoras de energía independientes, establezcan nuevos

proyectos. Específicamente, la reducción del riesgo de productoras de energía independientes implica subsidios y garantías gubernamentales para la venta de la energía producida mediante acuerdos para la compra de energía a esas productoras por un precio fijo y durante un tiempo determinado. Ello garantiza un ingreso a largo plazo para el sector privado, mientras que expone a los países anfitriones, como Sudáfrica y Senegal, a riesgos comerciales y exacerba su deuda externa, dado que brindan garantías soberanas para la financiación privada.

Centrarse en atraer financiación privada también implica que se asignen fondos insuficientes para medidas de transición justa que no se consideran “financiables”, dado que no generan ganancias directas sobre la inversión −por ejemplo, un sistema de aranceles socialmente sensible, formación en competencias y programas de empleo sensibles al género o la transferencia de tecnología. Las ATEJ no apoyan la fabricación de energía renovable local, que es donde se encuentran la mayoría de los empleos de alta calidad y la creación de valor económico y, por lo tanto, no contribuyen al desarrollo industrial verde soberano, al empleo de largo plazo y a los beneficios para la comunidad −tan solo el 0,6 % de las contribuciones comprometidas a la ATEJ firmada por Sudáfrica se destinan al desarrollo de competencias, la diversificación económica y la inclusión social. Además, debido a que los productores de energía privados no solo necesitan recuperar sus costos operativos, sino que además intentan obtener ganancias, ello podría dar lugar a tarifas de energía más elevadas que incorporen márgenes de ganancia y pagos de intereses, lo cual exacerba la pobreza energética. Por último, en las negociaciones de las ATEJ no se han incluido a la sociedad civil ni a las comunidades. Los acuerdos se negocian a puertas cerradas entre el G7, que negocia como bloque, y países individuales, que con frecuencia han expresado preocupación respecto de las condiciones de estos acuerdos, que a menudo permanecen ocultos al público. Los movimientos sociales y los sindicatos han realizado propuestas alternativas de financiación justa para el clima (Global Energy Justice Workshop Collective, 2023), que se centran en la cancelación de la deuda (Baloyi y Krinsky, 2022), las reparaciones climáticas y las inversiones públicas, en lugar de reducir el riesgo de las inversiones privadas.

Este panorama de financiación parece estar muy alejado de la vida diaria de las personas. Pero la financiación mundial en la for- ma de préstamos, acciones o cualquier otro instrumento se las ingenian para figurar en proyectos concretos de energía renovable, como Hyphen o el parque eólico Taiba N’Diaye en Senegal, que tienen efectos considerables en la vida de las personas.

Aventuras de inversión en Senegal: el parque eólico Taiba N’Diaye

Chris Antonopoulos, el director ejecutivo de Lekela, hace alarde de que hace falta tener “espíritu aventurero” para construir parques eólicos en África (Lekela Power, 2021). Lekela es una empresa de energía renovable con sede en Londres, que construyó el parque eólico Taiba N’Diaye, de 160 MW, en Senegal. Lo que para algunos es una aventura de inversión, para otros implica la destrucción de sus medios de subsistencia.

Este parque eólico es un caso ejemplar de cómo la producción de energía renovable se convierte en un activo y da oportunidades a inversores con fines de lucro que suelen estar radicados en el norte global. Ello es posible mediante un entorno institucional de reducción del riesgo tanto del Gobierno de Senegal, como de las instituciones internacionales de financiación del desarrollo, que crean el entorno seguro y estable para los inversores europeos. El parque eólico es considerado un activo invertible, del cual inversores distantes esperan una ganancia considerable, pero al mismo tiempo es el hogar y lugar de protesta de las comunidades afectadas.

La política energética de Senegal ha estado orientada a la creación de un “entorno de reducción del riesgo”, que permite la producción de energía privada. En una reciente reforma del sector de la energía, el Gobierno pasó a apoyar la financiación privada al eliminar barreras regulatorias y crear un entorno propicio para los inversores internacionales. La característica principal de la reforma es la desagregación de Senelec, la empresa de electricidad nacional y la compradora de electricidad en proyectos de energía renovable, y el fortalecimiento de actores privados en la producción de energía (Ward, 3 de mayo de 2021). Las productoras de energía independientes realizan ofertas para obtener los derechos de producción, mientras que la planificación energética de largo plazo de los reguladores ofrece a los inversores una base estable para adoptar decisiones de inversión de largo plazo. La liberalización del mercado de electricidad lo abre a la producción de energía privada y la planificación nacional procura volverla atractiva para el capital extranjero.

De acuerdo con esta orientación de las políticas, desde comienzos de los años 2010, el porcentaje de producción de las productoras de energía independientes ha aumentado a la mitad de la capacidad total instalada de Senegal, fundamentalmente mediante la inversión extranjera directa. Alrededor de la mitad de la capacidad de producción de energía solar del país es propiedad de empresas francesas (Meridiam, 31 de mayo de 2021). El poder colonial ha vuelto o quizá nunca se retiró.

El parque eólico Taïba N’Diaye se adapta bien a la agenda de políticas energéticas de Senegal. La empresa francesa Sarreol desarrolló el proyecto y más tarde lo vendió a Lekela, que posteriormente lo desarrolló para obtener rentabilidad financiera con un préstamo de la Corporación Financiera de Desarrollo Internacional, la institución del Gobierno de Estados Unidos que se dedica a la financiación para el desarrollo, y una garantía de inversión del Organismo Multilateral de Garantía de Inversiones del Banco Mundial. Lekela era propiedad de dos fondos de capital de infraestructura europeos con estructuras de propiedad poco transparentes cuando comenzó la construcción del proyecto y desde entonces fue vendida a otros inversores. En la actualidad, el parque eólico consiste de cuarenta y seis turbinas eólicas, un número que se espera que pronto se duplique, y afecta a más de diez localidades con una población de alrededor de veinticinco mil habitantes.

La necesidad de los inversores privados de un mayor grado de seguridad genera una constelación de financiación y modelos de negocios que ameritan un examen más detenido. Lekela vende la electricidad producida a la empresa nacional de energía Senelec y utiliza las ganancias para pagar los préstamos a los acreedores y otorgar las ganancias anticipadas a sus accionistas. Por lo tanto, Lekela está obligada a funcionar con fines de lucro.

Para no arriesgar este flujo de efectivo, el modelo de negocios está garantizado mediante una reducción del riesgo fiscal. El Gobierno de Senegal brinda un conjunto de garantías para la compra de electricidad y el Banco Mundial hace lo mismo con los riesgos políticos, de modo de proteger a los inversores contra casi todos los peligros.

En virtud de un denominado Acuerdo de Compra de Electricidad, Senelec está contractualmente obligado a pagar toda la energía producida, incluso si no hubiera demanda o si la red está sobrecargada. Ello garantiza las ganancias de Lekela. Además, Senegal brinda una garantía soberana para cubrir la posibilidad de que Senelec incumpla sus pagos.

Los inversores también pueden recurrir a las garantías de riesgo político que brinda el Banco Mundial, como el seguro contra riesgos políticos o la garantía parcial contra riesgos. Estas garantías pueden utilizarse en casos de impago por Senelec y el Estado, expropiación o guerra y disturbios. Por consiguiente, además de los riesgos del proyecto o tecnológicos, los inversores están cubiertos contra prácticamente toda forma de inseguridad.

La lógica del lucro detrás de la financiación del proyecto y la necesidad de obtener ganancias constantes para servir a los acreedores da lugar a desigualdades al final de la cadena en el parque eólico, es decir, que afecta a las comunidades locales. Estas desigualdades son incluso más pronunciadas si se compara la narrativa de inversión de Lekela y la disidencia comunitaria.

Los inversores cuentan la historia de los beneficios para el desarrollo de los proyectos de infraestructura a gran escala, como la creación de empleo. Según Lekela, en total 380 personas han sido empleadas durante la construcción, todas de localidades aledañas. Sin embargo, los habitantes locales expresan su clara frustración con respecto a la contratación, dado que los puestos de trabajo son temporales y en su mayoría poco cualificados.

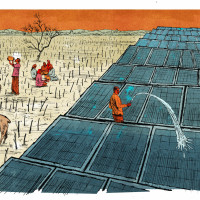

Esto es incluso más problemático debido a que se ha expropiado la tierra comunitaria para construir el parque eólico y se ha privado así a la población de sus medios de subsistencia. Alrededor de 420 productores agrícolas afectados por el parque eólico han recibido indemnización. Es cierto que la indemnización ha sido superior al monto nacional habitual. Si bien esto puede considerarse un gesto noble por parte de Lekela, la cuestión de la tierra representa la di- visión fundamental entre los inversores y la comunidad afectada. La historia de inversión de Lekela proclama una modernización − aunque imaginaria− de tierra agrícola a parque eólico y presupone progreso y desarrollo, pero las conversaciones con los agricultores dan una sensación muy diferente de lo que significa la tierra agrícola, que es sinónimo de vida y es la base de la alimentación y los ingresos. La indemnización puede ayudarlos a sobrellevar sus vidas en el corto plazo, pero no puede compensar la pérdida de su tierra. La cuestión de la tierra trae el colonialismo del pasado al presente. La idea dominante de terra nullius justificó el reparto de África durante el colonialismo, en el que se organizó el acaparamiento de tierra para la economía colonial de las plantaciones de forma tal que aún hoy vemos los patrones del extractivismo (Dieng, 29 de abril de 2021).

Desde el punto de vista de los inversores, el parque eólico es un caso exitoso de la modernidad y el desarrollo. Supuestamente ha mejorado las vidas de los habitantes locales, por ejemplo, mediante la construcción de un mercado, un centro informático en la escuela y paneles solares para los agricultores locales. La historia de inversión oficial es ilustrada con mujeres que bailan para expresar su alegría por las inversiones. Se basa en casi todos los clichés conocidos −exactamente el modo en que Binyavanga Wainaina nos enseñó que no se debe escribir sobre África (Malik, 7 de octubre de 2022; Wainaina, 2 de mayo de 2019).

La historia parece ser una filantropía pura que da lugar al progreso en las localidades aledañas, mientras que los inversores tienen la autoridad moral. Según ellos mismos afirman, el proyecto es “más que un parque eólico”. Lo que la historia de Lekela oculta es que el parque eólico generará ganancias estables a largo plazo al desarrollador europeo, gracias a los instrumentos de reducción de riesgo mencionados anteriormente. Sin embargo, esto hace que el riesgo se transfiera a las comunidades afectadas y a las cuentas del Estado, por lo que añade una carga para el presupuesto estatal y proporciona ganancias de corto plazo a la empresa privada.

Si se considera el parque eólico desde una perspectiva macro, se observa que las inversiones en energías renovables, incluso en un solo parque eólico en Senegal, están cada vez más interconectadas en los circuitos de las finanzas internacionales. Lekela fue vendida recientemente a la empresa operadora Infinity, que es propietaria de muchas productoras de energía independientes en África. Resulta difícil de creer que los propietarios anteriores no obtuvieron muchas ganancias a partir de esta venta, que implica una desconexión entre los propietarios del proyecto y la comunidad. Como mínimo, Lekela ha estado trabajando con las comunidades locales durante varios años. El nuevo propietario no tiene esta relación, lo cual podría socavar toda responsabilidad y rendición de cuentas por los impactos del parque eólico en las comunidades locales (Baker, 2022). Por último, la posible influencia que los instrumentos de reducción de riesgo otorgan a las organizaciones multilaterales resulta problemática a nivel macropolítico. La amenaza de activar una garantía de riesgo es una medida disciplinaria, en el sentido de que si el Gobierno no paga debe cubrir la suma garantizada, ya que el Banco Mundial posee la facultad de imponer reformas estructurales en el sector de la energía y socavar de ese modo la soberanía del Estado.

La historia de Lekela oculta estas jerarquías estructurales y les resta importancia. Su narrativa incluye tan solo dos funciones: el inversor benevolente europeo y los beneficiarios agradecidos. A pesar de esta narrativa −o precisamente debido a ella−, es importante recordar que el parque eólico Taïba N’Diaye es una inversión que aporta ganancias a inversores ricos y poderosos por la venta de electricidad que la población senegalesa paga con las tarifas eléctricas.

Por lo tanto, es importante destacar que las personas afectadas por el parque eólico formaron un colectivo para defender los derechos de la comuna de Taïba N’Diaye (Taxawu Askan Wi), a fin de hacer frente al desarrollador de proyecto, exigir su participación equitativa de los ingresos y el derecho de que se tenga en cuenta su opinión en las decisiones que las afectan. Debido a la superioridad financiera de Lekela y a su poder para definir la narrativa de inversión, es fundamental ver qué ocurre en los márgenes, de qué modo las personas afrontan dificultades día a día para contrarrestar las desigualdades de poder financiero y lo que esas luchas reflejan sobre la estructura financiera mundial.

Sueños de hidrógeno verde en Namibia

Del noroeste al sur de África, la fiebre de las energías renovables adopta otra forma. Mientras que el parque eólico Taïba N’Diaye se construyó para abastecer a la red eléctrica nacional, la economía emergente del hidrógeno en Namibia está orientada a servir a las economías europeas. Desde 2021, Namibia ha abierto sus puertas a un sinnúmero de inversores, empresas y asistencia técnica, y ha incorporado instituciones de reducción del riesgo para que se ajusten a su meta de convertirse en una “superpotencia de hidrógeno verde” (Green Hydrogen Organisation, 2023).

Reducción del riesgo fiscal

Para lograrlo, el Estado namibio ha construido una arquitectura de financiación combinada que se basa en gran medida en un ecosistema internacional público-privado de reducción del riesgo para poner en marcha la incipiente economía del hidrógeno (Gabor y Sylla, 2023). Ello incluye una plataforma de financiación combinada denominada SDG Namibia ONE para ampliar la escala de reducción del riesgo de la estrategia de hidrógeno verde y las iniciativas del sector privado correspondientes. El capital concesional de SDG Namibia ONE está destinado a disminuir el costo total de capital y, por consiguiente, brindar protección fiscal a lo que el país espera que será un flujo de inversores privados, listos para desembolsar su capital y satisfacer las necesidades de inversión. La plataforma, que fue lanzada en la COP27 celebrada en Egipto, ahora es gestionada en el Fondo de Inversión Ambiental de Namibia por dos organiza- ciones neerlandesas: Climate Fund Managers e Invest International Dutch.

La Plataforma ha recibido fondos para asistencia técnica de Investment International (cuarenta millones de euros) y del Banco Europeo de Inversiones (cinco millones de euros) para adaptar la plataforma a las necesidades de los inversores, y un préstamo adicional en condiciones favorables de quinientos millones de euros del Banco Europeo de Inversiones. El Gobierno está utilizando este dinero para financiar sus participaciones de capital en el prestigioso proyecto de hidrógeno de gran escala administrado por Hyphen Hydrogen Energy.

Si bien esos enfoques aún son muy recomendados por el Grupo del Banco Mundial (World Bank Group, 2023) y la OCDE (Orga- nization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021), se corre el riesgo de que los países se vuelvan más vulnerables a crisis de la deuda y, en definitiva, amplíen el poder y la influencia de los prestamistas financieros. Namibia ya tiene una deuda sobera- na del 60 %, por lo que estos préstamos se suman a la deuda externa

total del país y ejercen más presión sobre el presupuesto nacional, ya que si uno de los proyectos fracasa, el Estado y los ciudadanos namibios serán quienes tengan la carga de pagar la deuda. Además, tanto los acreedores como los desarrolladores del proyecto son parte de una red europea que intenta capitalizar y utilizar el hidrógeno verde y sus derivados para sus propios fines. Un representante de un banco local que estaba encargado de elaborar las regulaciones de la inversión de Hyphen, lo resumió como sigue: “En realidad, se trata de dinero destinado a pagar los salarios europeos. Existen estos grandes contratos de compraventa de múltiples años, pero entre instituciones europeas”.

Ecosistema de reducción del riesgo

La fiebre del nuevo“petróleo verde”y la creación de un entorno propicio ha puesto en alerta a muchos Gobiernos e inversores. Namibia ha firmado un memorando de entendimiento con Alemania, los Países Bajos y la Unión Europea para la exportación de hidrógeno verde. Otros inversores, como Anglo American, el Puerto de Róterdam, Bélgica y varias empresas japonesas están ejecutando sus propios proyectos relacionados con el hidrógeno.

El proyecto más importante se encuentra en el parque nacional Tsau Khaeb de la Iniciativa de Desarrollo del Corredor Meridional y es administrado por Hyphen −un consorcio entre la empresa de energía alemana ENERTRAG y la empresa de inversiones Nicho- las Holding. La empresa de inversión secreta está registrada en las Islas Vírgenes Británicas, un conocido paraíso fiscal, aunque el brazo operativo es administrado por su empresa subsidiaria Principle Capital, que ha estado involucrada en un controvertido proyecto de biocombustibles en Mozambique (Grobler, Lo y Civillini, 15 de noviembre de 2023). La inversión prevista abarca 9400 millones de dólares, el equivalente al producto interno bruto (PIB) de Namibia en 2020. El plan es construir paneles solares y electrolizadores para producir hidrógeno verde en una zona protegida de 4000 km2, casi exclusivamente para exportarlo a Europa. El Gobierno namibio prevé la construcción de diez a quince proyectos adicionales de carácter similar en el parque nacional.

Para abordar los riesgos políticos y regulatorios que pueden impedir la inversión de capital extranjero en su industria incipiente, como el acceso “complicado” de empresas extranjeras a la tierra, las fuertes protecciones ambientales o los requisitos de visado, el Gobierno alemán, entre otros, han otorgado un programa de asistencia técnica a Namibia. La asistencia es brindada por las empresas jurídicas multinacionales que elaborarán las políticas y normativas. El fin último es crear un “entorno propicio” que sirva a los intereses de los inversores alemanes y europeos. Por ejemplo, las empresas seleccionadas para los proyectos Hyphen son principalmente de origen alemán o europeo.

Reducción del riesgo normativo

Se están realizando otros ajustes normativos propuestos para adaptarse a la economía del hidrógeno. En la actualidad no existe legislación específica para la producción del hidrógeno verde con fines de exportación, ni un sistema de seguridad adecuado para regular la producción, el almacenamiento, transporte y la utilización del hidrógeno y sus derivados (como el amonio). A fin de elaborar dichas normativas, Namibia está utilizando la costosa asistencia técnica extranjera de estudios jurídicos y consultorías, y las recomendaciones de organizaciones como el Banco Mundial y McKinsey. El dirigente del movimiento social Reposicionamiento Afirmativo Job Amapunda sostiene que Hyphen está trabajando estrechamente con el Gobierno namibio para crear un marco jurídico para su economía de hidrógeno (Beukes, 8 de mayo de 2023) y señaló que un coordinador de proyectos del sector privado está elaborando el futuro marco regulatorio para toda la industria emergente en Namibia, adaptado a sus preferencias, requisitos y necesidades.

Aunque el Gobierno namibio y las partes interesadas europeas celebran los múltiples acuerdos, estrategias y asociaciones que se han establecido en tan solo unos meses, la sociedad civil de Namibia ha señalado el peligro de la dependencia financiera, la degradación ecológica y la exclusión social recurrentes en medio del entusiasmo con el hidrógeno verde.

En cuanto a las reglamentaciones, las enmiendas legislativas para favorecer a los desarrolladores del proyecto y su afán por garantizar un amplio espacio de producción para el hidrógeno verde pueden facilitar el acaparamiento de tierra y agua. En el caso de Hyphen y su trayectoria actual, el proyecto llevará una economía de enclave a la localidad de Lüderitz, que no está para nada preparada. Es decir, una economía orientada a la exportación dominada por capital no local. Mientras que Hyphen anunció la creación de quince mil empleos y tres mil adicionales durante la fase de construcción, similar al caso de Senegal, la mayoría de estos empleos serán temporales y estarán destinados a trabajadores no cualificados.

Aparte del trabajo precario y las condiciones de vida en el lugar, también existen riesgos socioecológicos de que surjan conflictos res- pecto del agua y la destrucción ecológica. Ellos incluyen el vertido de salmuera de plantas desalinizadoras en el mar o en aguas subterráneas, el uso de reservas limitadas de agua dulce −según ha planificado el proyecto Daures, financiado por el Gobierno alemán−, el uso de parques nacionales para el proyecto Hyphen y el gran impacto de la infraestructura planificada, como puertos y plantas en los ecosistemas terrestres y marinos. Los mercados financieros hacen la vista gorda a estos riesgos socioecológicos, siempre y cuando no pongan en peligro sus inversiones. El resultado es la socialización de los riesgos y la privatización de las ganancias, especialmente para las élites y los inversores internacionales, que perpetúan el endeudamiento del Estado con bancos internacionales y limitan el espacio para la intervención de la sociedad civil.

La sociedad civil ha expresado preocupación sobre la falta de transparencia y rendición de cuentas con respecto a los procesos de adquisiciones, acuerdos financieros y opciones normativas. Sin embargo, en lugar de reunirse con la sociedad civil y abordar sus preocupaciones legítimas de forma democrática y transparente, el Gobierno namibio “advirtió a la población local que no interfiera con el proyecto de hidrógeno verde Hyphen Hydrogen Energy” (Matthys, 1 de junio de 2023). Los inversores y políticos alemanes y europeos siguen pintando las asociaciones de hidrógeno verde como acuerdos entre partes iguales. La historia de la participación alemana en el pasado y presente extractivo de Namibia, incluida la ocupación colonial y el genocidio de los hereros y nama no forman parte de estas discusiones. Resulta sorprendente ver con qué rapidez se puede movilizar capital para el beneficio de los países ricos, mientras que aún no se han otorgado reparaciones ni se han pedido disculpas formales por las atrocidades coloniales cometidas por Alemania. Un activista describió la fiebre del hidrógeno verde en Namibia de la siguiente manera: “Queremos que se lo llame por lo que realmente es. Eso es importante. Aunque sigan demoliendo y saliéndose con la suya, se lo debe llamar por su nombre. Esto es imperialismo. Esto es colonialismo”.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

La necesidad de modelos de financiación democráticos y socialmente justos

El panorama presentado por estos casos de energía verde es ambivalente. Hay una necesidad urgente de financiación para proyectos de energía renovable. La crisis climática afecta en forma desproporcionada a algunos de los países y las comunidades más vulnerables del mundo. Sin embargo, la forma de financiación actual de la energía renovable puede aumentar esa presión, en lugar de aliviarla. Amenaza los esfuerzos para lograr justicia climática a nivel mundial. Las asociaciones de financiación, como las asociaciones para una transición energética justa, así como proyectos específicos de energía renovable, suelen ser una puerta de entrada para los intereses del norte global y pueden perpetuar el colonialismo verde. Las naciones ricas, las élites nacionales y las empresas multinacionales se benefician, y los países anfitriones y sus ciudadanos asumen los riesgos financieros y ambientales, mientras que se privatizan las ganancias y el Estado y los usuarios deben soportar los costos de la transición.

Siguiendo los pasos del llamamiento de los años setenta a un “nuevo orden económico internacional”, las iniciativas basadas en una perspectiva del sur global cuestionan cada vez más la arquitectura mundial de la financiación para el clima. La Iniciativa de Bridgetown (Mottley y Hoyer, 21 de julio de 2023), una propuesta de reforma financiera mundial impulsada por la primera ministra de Barbados, Mia Mottley, ha generado una mayor conciencia sobre la deuda climática y de la crisis de la deuda que se avecina. Hay cincuenta y dos países que ya están sobreendeudados o, en el caso de Namibia, que ya afrontan la quiebra. El reclamo de Mottley de derechos especiales de giro para el FMI generó entusiasmo. En la Cumbre para un Nuevo Pacto Financiero Mundial, celebrada en París en 2023, los dirigentes allí reunidos acordaron reestructurar la arquitectura de la financiación para el desarrollo de modo de que se reorienten los flujos de financiación y se garantice una participación equitativa del capital. Sin embargo, el ímpetu radical de la Iniciativa de Bridgetown fue efectivamente una causa perdida, dado que en la cumbre no se aprobó un programa de alivio de la deuda, sino tan solo un enfoque fragmentado. Se dejó de lado el verdadero impacto de la Iniciativa Bridgetown, que representa una importante oposición a la dinámica neocolonial en la financiación para el clima y un llamamiento para exigir flujos financieros justos.

Para lograr justicia en la financiación para el clima se necesita un debate y práctica constantes entre los movimientos sociales, la sociedad civil, el sector político y el sector privado. Pero a menos que este debate se base firmemente en cuestiones de contenido y aborde las desigualdades de poder, al instar a la justicia se corre el riesgo de caer en el denominado postureo ético. Ello quedó de manifiesto en las discusiones sobre las asociaciones para una transición energética justa. Como han exigido los sindicatos y la sociedad civil, las negociaciones sobre proyectos de inversión deben ser inclusivas y transparentes, no basadas en acuerdos secretos a puertas cerradas entre países donantes y países beneficiarios. Únicamente si se garantiza esto los actores de la sociedad civil podrán solicitar más financiación basada en donaciones, en lugar de préstamos condicionales.

Los reclamos de justicia en proyectos de energía renovable, como las productoras de energía independientes, plantean preocupaciones adicionales. Se necesita establecer modelos de financiación que transfieran a las comunidades afectadas una suma justa y fija de las ganancias obtenidas por los desarrolladores privados. Las personas cuya tierra es expropiada deberían ser indemnizadas porque a menudo eso es lo único que poseen. A nivel gubernamental, las normas de contenido local deberían exigir a los desarrolladores internacionales que creen valor económico nacional. Estos reclamos no son abstractos o utópicos. Pueden adoptarse fácilmente si hay voluntad política y espacio para hacerlo. Sin embargo, el hecho de que tales demandas estén tan alejadas de la realidad sobre el terreno demuestra que queda mucho por hacer. Es preciso que la sociedad civil y los movimientos en solidaridad con las comunidades directamente afectadas por la energía renovable ejerzan presión sobre la financiación internacional que invierte en esos proyectos.

Bibliografía

Alami, Ilias (2019). Money Power and Financial Capital in Emerging Markets: Facing the Liquidity Tsunami. Abingdon: Routledge.

Baloyi, Basani y Krinsky, Jezri (2022). Towards a just energy tran- sition: A Framework for Understanding the Just Energy Transi- tion Partnership on South Africa’s Just Transition. IEJ Policy Brief, (1). https://www.iej.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/IEJ-policy- brief-ClimateFinance1.pdf

Bello, Walden (16 de octubre de 2017). From Japanese bubble to Chinese time bomb. Transnational Institute. https://www.tni.org/ en/article/from-japanese-bubble-to-chinese-time-bomb

Beukes, Jemina (2023). World Bank gives Namibia green hydrogen road map. Erongo 24/7. https://www.erongo.com.na/energy-ero/ world-bank-gives-namibia-green-hydrogen-road-map2023-05-08

Dieng, Rama S. (29 de abril de 2021). The labor of land. Africa Is a Country. https://africasacountry.com/2022/12/the-labor-of-land

Dutta, Sahil J. y Thomson, Frances (2018). Financierización: guía básica. Ámsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Eberhardt, Pia (2023). Germany’s Great Hydrogen Race. Brussels: Corporate Europe Observatory.

Elsner, Carsten et al. (2021). Room for money or manoeuvre? How green financialization and de-risking shape Zambia’s re- newable energy transition. CASID / ACÉDI, 43(2), 276-295. https:// www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02255189.2021.1973971

Gabor, Daniela (2021). The Wall Street Consensus. Development and Change, 52(3): 429-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

Gabor, Daniela y Sylla, Ndongo S. (2023). Derisking developmen- talism: a tale of green hydrogen. Development and Change, 54(5), 1169-1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12779

Global Energy Justice Workshop Collective (2023). Change the sys- tem, not the climate: What is wrong with the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP)? Kassel: Global Partnership Network. https:// www.uni-kassel.de/forschung/files/Global_Partnership_Network/ Downloads/JETP_Pamphlet.pdf

Green Hydrogen Organisation (2023). Namibia. https://gh2.org/ countries/namibia

Grobler, John; Lo, Joe y Civillini, Matteo (15 de noviembre de 2023). Shadesofgreenhydrogen:EUdemandsettotransformNamibiaSha- des of green hydrogen: EU demand set to transform Namibia.Clima- te Change News. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/11/15/ green-hydrogen-namibia-europe-japan-tax-biodiversity-impacts/

Haag, Steffen y Müller, Franziska (2019). Finanzplatz Afrika. Grü- ne Finanzflüsse und afrikanische Energietransitionen. En Hen- ning Melber (ed.), In Deutschland Und Afrika-Anatomie Eines Kom- plexen Verhältnisses (pp. 58-73). Frankfurt: Brandes & Apsel.

Huffschmid, Jörg (2022). Politische Ökonomie der Finanzmärkte. Hamburg: VSA-Verlag.

Kalt, Tobias y Tunn, Johanna (2022). Shipping the sunshine? A critical research agenda on the global hydrogen transition. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 31(2), 72-76.

Lekela Power (2021). The spirit of an adventurer. https://lekela. com/articles/the-spirit-of-an-adventurer/

Mabey, Nick (2009). Delivering a sustainable low carbon recovery. Proposals for the G20 London Summit. Londres: E3G.

Malik, Nesrine (7 de octubre de 2022). How to Write About Africa by Binyavanga Wainaina review - a fierce literary talent taken too soon. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/ oct/07/how-to-write-about-africa-by-binyavanga-wainaina-review- a-fierce-literary-talent-taken-too-soon

Matthys, Donald (1 de junio de 2023). Geingob blasted for telling Namibians not to interfere with green hydrogen project, The Namibian. https://ww2.namibian.com.na/geingob-blasted-for-te- lling-namibians-not-to-interfere-with-green-hydrogen-project/

Meridiam (31 de mayo de 2021). Scaling Solar Kael, Senegal. https://www.meridiam.com/news/scaling-solar-kael-scaling-so- lar-kahone-senegal-installation-solaire-kael-installation-solai- re-kahone-senegal/

Mottley, Mia Amor y Hoyer, Werner (21 de julio de 2023). What It Will Take to Transform Development Finance. Project Syndica- te. https://www.project-syndicate.org /commentary/unlocking-de- velopment-finance-fourfold-task-by-mia-amor-mottley-and-wer- ner-hoyer-2023-06

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2021). The OECD DAC Blended Finance Guidance. París. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/the-oecd-dac-blended-fi- nance-guidance_ded656b4-en.html

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo [PNUD] (2013). Derisking Renewable Energy Investment. Nueva York: Uni- ted Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/ publications/derisking-renewable-energy-investment

UN Trade and Development [UNCTAD] (2023). A world of debt 2023. https://unctad.org/publication/world-debt-2023

Wainaina, Binyavanga (2 de mayo de 2019). How to Write About Africa. Granta. https://granta.com/how-to-write-about-africa/

Ward, Andrew (3 de mayo de 2021). Senegal’s journey from blac- kouts to gas and green energy progress is swift, but universal access to electricity will take time. Financial Times. https://www. ft.com/content/d6432b72-2ea8-11e8-97ec-4bd3494d5f14

World Bank Group (2023). The International Finance Corporation’s. Blended Finance Operations. Findings from a Cluster of Project. Per- formance Assessment Reports. Washington D. C. https://ieg.world- bankgroup.org /sites/default/files/Data/Evaluation/files/IFC_blen- ded_finance.pdf