Yalla, Yalla, Abya Yala Reaching out to Palestine from Latin America in times of genocide

Temas

Regiones

Written against the backdrop of genocide, this longread interrogates how state complicity with Israel’s settler-colonial project has persisted beneath “two-state” common sense, foregrounding grassroots organising, BDS, and South–South solidarity and urging a turn from symbolic outrage to effective action.

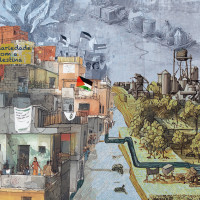

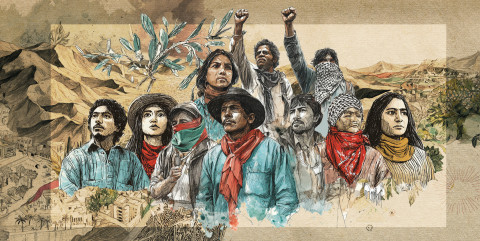

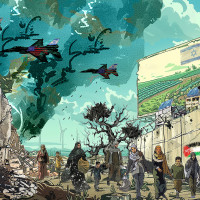

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Between Ambiguity and Contradictions

Abya Yala’s complex relationship with the Palestinian cause began with the role played by Latin American countries in the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in 1947. This recommended the partition of Palestine, and the handing over of more than half of its territory to a movement of European settlers who had been in the country for only a few decades, made up less than one-third of the population, and owned only 6% of the land. Aligned behind the leadership of the United States and the respective Zionist lobbies, the representatives of Uruguay, Guatemala, and Peru, as members of UNSCOP, and of Brazil, which held the presidency of the UN General Assembly, succeeded in persuading their fellow Latin American nations to support the partition of Palestine.2

Latin American states made up a third of the then brand new United Nations (created just two years earlier and having barely 50 members): 13 voted in favour of the partition,3 six abstained,4 and only Cuba voted against it.5 At a time when decolonisation was just beginning and most countries in Africa and Asia refused to recognise Israel, Abya Yala lent its support to the materialisation of the Zionist colonial project.6 As Argentinean historian Miguel Ibarlucía notes, the divided nature of the vote at the UN evidences that there was no global consensus, rather it was imposed by Western states –with the support of Latin American countries– on the Arab world, which was united in rejecting it.7

A number of factors explain Abya Yala’s support for partition. On the one hand, these countries had been formally independent for over a century at this point, and were therefore not as interested in decolonisation as was the rest of the Global South.8 Moreover, they had practically no knowledge of the Palestine question or the Arab world.9 In addition, the Jewish Agency lobby was very persuasive in a Western world shaken by the horrors of Nazism.

Those who wonder how a region that had suffered five centuries of Europe’s most brutal colonialism failed to see the colonial and racist nature of the state that was being forced on Palestine should remember that these national states were forged by local elites who were descendants of European settlers, and that the colonial nature of power and knowledge continues to dominate politics, society, and thinking in Abya Yala, as de-colonial analysts have pointed out10. This is why, 78 years later, countries in the region still need to self-critically examine their vote in 1947, alongside their seven-decade-long close ties with the state of Israel – this need is all the more urgent after two years of genocide in Gaza.

Another factor that needs to be considered is the Palestinian diaspora in Abya Yala and its specific characteristics.11,12 While the diaspora is diverse, most Palestinian immigrants came to Abya Yala in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and were Christian.13 In the countries where they settled (Chile, Honduras, El Salvador, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Colombia) they assimilated easily into the receiving society, prospered, and attained significant economic, cultural, and political influence. Their insertion into bourgeois classes14 meant that they often distanced themselves from the Palestinian cause – which is associated with the Left and with armed struggle – and identified with right-wing political positions, from the Chile of Augusto Pinochet to the El Salvador of Antonio Saca and Nayib Bukele (though some, like Shafik Handal, were revolutionaries). For these immigrants, who left Palestine before the Nakba and who never lived under Israeli occupation, the connection with their homeland was more affective and cultural than political. However, as in other diasporas, politicisation often occurred later, especially among third- or fourth-generation Palestinians, who sought to connect with their origins through the recovery of their language, identity, and collective memory, and through political activism, academic work, and literature.

This process was also linked to the increased international legitimacy of the Palestinian cause as a result of the successful diplomacy of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) under the leadership of Yasser Arafat, starting in the 1970s. In the case of Chile, for example, third- and fourth-generation Palestinians are now active in promoting the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement – especially university students, through the General Union of Palestine Students (UGEP) – and coordinate their activism with other social movements. This commitment has significantly strengthened the struggle against the current genocide. However, as Chilean researcher Cecilia Baeza has highlighted, there remains a strong contrast between the unity and sense of purpose that drives the Zionist pro-Israel lobby and the disparity of class and ideological interests among the Palestine diaspora in Abya Yala.

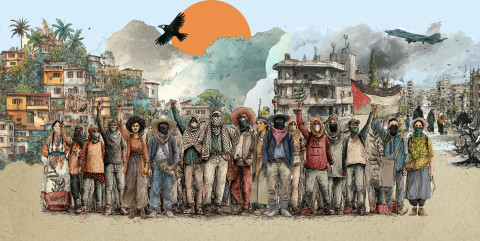

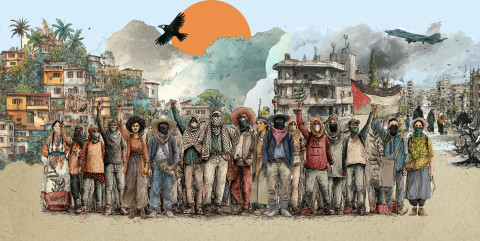

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Spectre of Israel Hovering Over Guerrilla Groups, Dictatorships, and Transitions

According to Baeza, Latin American countries have not adopted a consistent approach to the Palestine issue over the years, so that identifying regional trends necessarily involves simplifications.15 Despite their countries’ votes in 1947, over the following decades, successive governments in the region sought to maintain a pragmatic stance that balanced the interests of both their Arab and Jewish communities, as well as their commercial relations with Israel and the Arab countries. Thus, in every crisis, government discourse has condemned the violence on ‘both sides’ and called for international law to be respected – a stance that has tended to favour Israel. With exceptions such as Cuba, Sandinista Nicaragua,16 and Bolivarian Venezuela,17 while relations with Palestine and Israel have been shaped by Latin American countries’ changing interests and by the ideologies of their governing parties, maintaining close ties with Israel has generally been state policy.

In the period from the partition vote in 1947 to 1974, within the framework of the Cold War and alignment with the United States, most Latin American governments maintained a favourable position towards Israel, although with significant nuances depending on the country and the government’s orientation. However, factors such as the recognition by the United Nations of newly-decolonised countries from Africa and Asia in the 1950s and 60s, the emergence of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961, the Israeli occupation of the Arab territories in 1967, and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) embargo on countries that supported Israel in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War led states in Abya Yala to seek to improve their relations with Arab countries and to show greater support for the Palestinian cause. In 1974, the acceptance of the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people with observer status in the United Nations, also improved relations. Thereafter, in the 1970s and 80s many Latin American countries recognised the PLO, and it opened offices in several countries in the region, including Cuba, Nicaragua, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and Chile.

However, during this same period, even as most African states broke off relations with Israel in 1973, countries in Abya Yala – several of which were now ruled by authoritarian and dictatorial governments – became the leading beneficiaries of Israeli cooperation programmes, which included funding for both agricultural and military modernisation. Indeed, from 1970 to the mid-1980s, Israel’s main exports to the region were weapons.18

Of course, states and governments cannot be equated with their peoples (as has been evident during the Gaza genocide) and so it is unsurprising that outside of, and despite, the stance of their governments, direct solidarity between Palestine and the people of Abya Yala also emerged during the 1960s and 1970s, including links between political guerrilla organisations in the region and those in Palestine and the Arab world.19

Cuba played a key diplomatic and political role during this period, with initiatives such as the 1966 Tricontinental Conference held in Havana, which brought together revolutionary movements from the three continents of the South. That gave way to the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAL), with its Tricontinental magazine, which was a major voice for Third-Worldism at this time. Cuba also facilitated strategic information and military training exchanges among guerrilla organisations from the Southern Cone,20 Colombia, Central America, and Palestine.21 In these circles, Palestinian resistance, led by the PLO, was seen as a national liberation and anti-imperialist struggle.

However, the defeat of the guerrilla movements in Abya Yala in the 1970s and 1980s22 coincided with the cessation of a cycle of Palestinian armed struggle, after the PLO was forced to relocate from Lebanon to Tunisia in 1982. Thereafter, the organisation laid down its weapons and embraced diplomacy: issuing Palestine’s Declaration of Independence in 1988, participating in the Madrid Conference of 1991, and signing the Oslo Accords in 1993–1995. In Abya Yala, the authoritarian and brutally repressive regimes and dictatorships that emerged in this period not only decimated militants and organisations through state terrorism, they also dissolved connections and shared memories.23 The fate of the vast majority of these militants was death, forced disappearance, exile, or prolonged political imprisonment. These defeats prompted long and complex debates, and also discredited armed struggle among some intellectuals, leaders, and activists across important sectors of the Left.24

During the 1970s and 1980s, Israel, acting as a proxy for the United States, armed and trained authoritarian regimes and death squads in counterinsurgency tactics in the Southern Cone and in Central America.25 In addition to its political aims, Israel had an economic interest in this strategic alliance with dictatorships and their armed forces: the region received a third of all Israeli weapon exports during the 1980s.26 As the historian Gerardo Leibner notes, Israeli collaboration provided diplomatic and political coverage to these regimes –and very likely intelligence.27

It did not matter to Israel that these dictatorial regimes were explicitly anti-Semitic. For example, Argentina’s military junta believed there was a conspiracy (known as the Andinia Plan) to establish a Jewish state in Patagonia. Even after it tortured the journalist Jacobo Timerman and other Jews to extract information on alleged plans by the Israeli army to invade Argentina,28 Israel did not withdraw its support for the Junta: it continued to supply it with the weapons it used during the Malvinas/Falklands War.29

Military ties with Israel were also critical in the establishment of the Colombian United Self-Defence Groups (AUCs) and other far-right paramilitary groups which were responsible for 45% of the 400,000 victims of Colombia’s internal conflict.30 Carlos Castaño, who was the top leader of the AUCs, travelled to Israel for military training in 1983.31 The authoritarian regimes that ruled Paraguay, Guatemala, and Honduras likewise maintained close military and intelligence relations with Israel during the 1980s and into the following decades. It is no coincidence that in 2018 these were the first countries to announce their decision to move their embassies to Jerusalem, following Trump’s lead.32

During the mid- to late-1980s, the peoples of Abya Yala were too focused on the challenges of democratic transition and combating the impunity of the perpetrators of state terrorism to engage in significant pro-Palestine solidarity. However, interest in the Palestinian cause was rekindled in late 1987 when the First Intifada broke out, stirring growing international sympathy. The Palestinian Declaration of Independence, announced in Algiers in 1988, saw renewed support for the Palestinian cause: 10 Latin American countries33 voted to adopt UN General Assembly Resolution 43/177 (1988) recognising the Declaration, although only Nicaragua and Cuba formally recognised the State of Palestine at this time.

Following the end of dictatorships and authoritarian regimes in Abya Yala in the 1980s and 1990s, almost all governments in the region, whether conservative or progressive (with the exception of Cuba and Nicaragua), have either established or maintained military and security relations with Israel, focusing on four areas: weapons, security systems, cybersecurity and intelligence, and training security forces in ‘combating terrorism’ and ‘counterinsurgency’. Israel has participated in weapons fairs in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. As part of his security policy and militarisation of Araucanía or Wallmapu, Chile’s Sebastián Piñera signed more treaties with Israel than any other Chilean president apart from Pinochet. Similarly, Brazil, under the Workers’ Party (PT) government signed military contracts with Israel worth around 1 billion dollars, as revealed in a 2011 report by the Palestinian organisation Stop the Wall. The results of these contracts can be seen in the methods, practices, and equipment used by the police and the army in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, with a huge cost for their mostly young Black population.34 It is because of links such as these that the BDS movement is promoting a military embargo against Israel and also seeks to connect the Palestinian cause with anti-colonial, Indigenous, anti-racist, and anti-militarist struggles across Abya Yala.

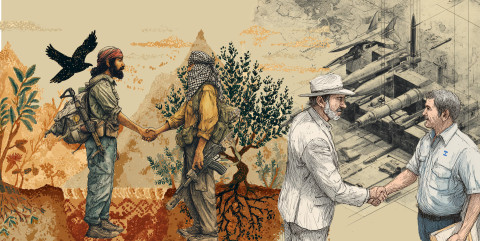

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

The Oslo Disaster; Is Another World Possible?

The popular and massive uprising of the first intifada would be dismantled by the so-called ‘Oslo process,’ a trap into which not only a large part of the Palestinian people in the occupied territory and in the diaspora fell, but also their supporters around the world. That popular enthusiasm for the process was inevitable, given the legitimacy conferred on it by Arafat's leadership.

The critical voices and warnings raised by figures as diverse as Edward Said (who called the Oslo Accords a ‘Palestinian Versailles’) and 10 Palestinian political parties (extending from Islamist to Marxist) went unheeded. The so-called ‘peace process’ was a ruse35 that aimed to quell the Intifada and ensnare the oppressed in endless and illusory negotiations with their oppressors, under the auspices of an imperial power (the United States) that was anything but an honest mediator, given its historical and unconditional support of Israel.36

The implications of the Oslo process for the Palestinian people were manifold and tragic. It is true that the accords enabled many exiled Palestinians (including Arafat himself) to return to Palestine and gave the Palestinian Authority (PA) the power to administrate education and other public matters autonomously (thereby freeing Israel from its responsibilities as the occupying power). It is also true that they furthered diplomatic efforts in the United Nations. But, more importantly, they also hid the truth of Israeli domination behind a facade of Palestinian self-government, which allowed Israel to gain legitimacy in the eyes of, and to secure recognition by, a number of Arab, Muslim, and Global South countries.37 Moreover, the PA’s chief responsibility under the process was – and continues to be – guaranteeing the safety of Israeli settlers in the occupied territories, including by sharing intelligence – and collaborating – with Israel to repress the resistance of their own people.38

No less pernicious was the epistemic trap that Oslo created in much of the politics, public opinion, academia and the solidarity camp worldwide. Not only because of the fallacious belief that the process would lead to the birth of a Palestinian state, but also because it established a misleading paradigm that persists to this day: that of ‘the two sides’ which had to negotiate a peaceful solution to the ‘conflict’, obscuring the asymmetry of power and responsibility between them. This distortion that puts the oppressor and the oppressed – in this case, the coloniser/occupier and the colonised/occupied – on an equal footing is known in the Southern Cone as the “theory of the two demons”39 or of the two opposing violences.

With the installation of this false paradigm, the concepts of national and anti-colonial liberation struggles were forgotten or relegated to the margins. At the same time, the decision by Arafat and his party to lay down their weapons resulted in the de-legitimisation of armed struggle. That de-legitimisation was compounded by the fact that in response to the massacre of 29 Palestinians engaged in Ramadan prayers in the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron in February 1994, Hamas and the Islamic Jihad launched a wave of suicide attacks in Israeli territory, which lasted several years and damaged the image of the Palestinian cause in the West. Following the attacks on the Twin Towers in 2001 and the War on Terror launched by the United States and its allies, and with a Second Intifada underway, it was very easy to demonise Palestinian resistance as ‘terrorism’.

This demonisation occurred not only in public opinion, the mainstream media, and the political system, but in much of the Left as well, including in Abya Yala. Islamism is not easily accepted in a Christian-majority continent40 where leftwing parties are also secular and distrustful of any religious expression. In turn, the mere existence of the PA and its docile president claiming to represent the PLO only served to reaffirm what the legitimate path is, who are considered good Palestinians and who are considered bad Palestinians. As a result, it seems today one cannot speak out against the genocide without first condemning ‘Hamas’s terrorism’: if not, one risks being discredited or threatened with criminalisation for ‘supporting terrorists’. Of course, such condemnations are wielded by those who have never condemned Israeli state terrorism and who parrot clichés without knowing anything about Palestinian resistance or about Hamas.

Oslo had another consequence: the Palestinian embassies established in Abya Yala countries – which also opened their own in Ramallah – became the main – sometimes the sole – reference point for pro-Palestine solidarity groups, governments, and society in general. The emergence of this new political actor distorted the historical path of Latin American solidarity with the Palestinian liberation struggle in a region where the opportunities for direct contact and exchange with Palestinian activists are much fewer than in the northern hemisphere, due to economic and geographical limitations. Compounded by the language barrier, this reduces the possibilities of hearing Palestinian voices and views – in particular those of the younger generations – beyond the official discourse of the PA.

The Oslo Accords – which set back the Palestinian cause by 30 years – were signed in the context of the dissolution of the Soviet bloc, the end of the Cold War, and the crisis of the socialist and revolutionary utopias. In Abya Yala, they coincided with the ‘lost decade’ (1990s) of the neoliberal era, inaugurated with the defeat of the Nicaraguan revolution in the 1990 elections and the ensuing crisis of Sandinismo. During this time, with the exception of the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas (1994),41 the advancing reactionary forces and neoliberal capitalism, with its privatising and extractivist programmes, seemed unstoppable. In the era of US hegemony and the ‘end of History’, monolithic thinking imposed ‘a global colonialism […] neoliberal and post-modern […] a recolonization’.42

The beginning of the 21st century was marked by the outbreak of the “second intifada” in Palestine; what began as a popular uprising quickly turned into a bloody military confrontation due to the excessive violence of the Israeli forces and a crushing defeat of the resistance. By contrast, Abya Yala saw the resurgence of hope. One symptom of this newfound hope was the World Social Forum (WSF), first held in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in January 2001, as a counterpoint to the Davos Economic Forum, and held annually thereafter in different continents, under the slogan ‘Another world is possible’ – no doubt inspired by the Zapatista movement’s call for ‘A world in which many worlds fit’43. The WSF in Porto Alegre symbolised a break with the tyranny of neoliberal monolithic thinking and called on popular movements to build new transformative utopias.44

The Palestinian cause was present at the WSF from the beginning, although not without tensions, since the forum’s Charter of Principles defined it as a non-violent space that rejected armed struggle, even as Palestinians were in the midst of the Second Intifada. While Palestinian participation in the WSF was diverse, it was clear that the debate over the legitimacy of armed struggle was not an easy one in Abya Yala, where many social movements had (and have) a critical view of the guerrilla experiences of past decades (see footnote 24). This was compounded by the fact that the suicide attacks and the stigma of terrorism that had taken hold since the attack on the Twin Towers projected a negative image of Palestinian resistance throughout the world, including in Abya Yala.

The 2000s saw the rise of governments considered leftwing, progressive, or centre-leaning in Abya Yala: Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (2000), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil (2003), Néstor Kirchner in Argentina (2003), Tabaré Vázquez in Uruguay (2005), Evo Morales in Bolivia (2006), Oscar Arias in Costa Rica (2006), Cristina Fernández in Argentina (2007), Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua (2007), Fernando Lugo in Paraguay (2008), Mauricio Funes in El Salvador (2009), José Mujica in Uruguay (2010), and Dilma Roussef in Brazil (2011). During this period, and especially under the leadership of Lula da Silva, South American governments sought to articulate a regional political stance that was more independent of US influence.

In line with this new approach, these progressive governments expressed their support for the Palestinian people to various degrees. By the 2010s, 16 Latin American countries had recognised the State of Palestine,45 and several had established embassies or diplomatic offices in Ramallah. However, at the same time they also expanded relations with Israel, seeking to maintain a ‘balanced’ position. For example, in 2007 the Mercosur bloc countries (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay), three of which had progressive governments at the time, signed a free trade treaty with Israel. Eighteen years later, even with the current genocide in Gaza, no Mercosur government or social movement has called for the treaty’s suspension.

Brazil is an eloquent example: while the PT administrations stepped up diplomatic relations and economic cooperation with Palestine (valued at some 30 million dollars between 2006 and 2012), they also increased their weapons imports from Israel. Starting in 2000, Israeli military companies, led by Elbit Systems, became major suppliers of the Brazilian police and armed forces. Drones purchased from Israel have been used since 2010 in the militarisation of Brazil’s favelas and were also used during the 2016 Soccer World Cup. At the same time, President Dilma Rousseff refused to accept Dani Dayan (a leader of the West Bank settler movement) as ambassador to Brazil in 2015.

These contractions were seen during previous Israeli attacks on Gaza: in 2009, during Operation Cast Lead, only Bolivia under Evo Morales and Venezuela under Hugo Chávez broke off diplomatic relations with Israel. In 2014, during the most vicious offensive, known as Operation Protective Edge, while some Latin American governments raised their voices to condemn Israel slightly more loudly than did European countries, and five (Brazil, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, and El Salvador) recalled their ambassadors briefly from Tel Aviv, none broke off relations.

In the 2010s and 2020s, conservative sectors returned to power in several countries in Abya Yala, which then halted or rolled back their commitment to the Palestinian cause. The Jair Bolsonaro era in Brazil is the best example of this reversal. After coming to power with the support of the Zionist Evangelical sectors gathered in the ‘Bible bench’ of Parliament, Bolsonaro aligned his government with the US and ratified Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel (although the announced relocation of the embassy was never implemented due to pressures from Arab countries that are Brazil’s powerful commercial partners). In the first months of his administration, Bolsonaro signed six agreements with Israel on public security, defence, science and technology. In 2017, Netanyahu became the first Israeli head of government to visit the region: Argentina governed then by Mauricio Macri, Colombia by Juan Manuel Santos and Mexico by Enrique Peña Nieto; and in 2019 he was the first to visit Brazil.46

Paradoxically, the 2020s saw the development of the BDS movement in Abya Yala. Successful sports and cultural boycott campaigns prevented soccer players and artists (in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay) from travelling to Israel, and other campaigns were launched: for academic boycott (in Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia), against the penetration of the Israeli water company Mekorot (Argentina, Brazil), against Mexican multinational corporation CEMEX which has Israeli links (Colombia, Mexico), and against Israeli military companies Elbit and ISDS (Brazil). The Apartheid-Free Spaces campaign and the annual Israeli Apartheid Week spread across the region at this time. The BDS movement organised two regional events (in Santiago de Chile in 2017 and in Rio de Janeiro in 2018) and a political tour by musician Roger Waters, published a report on Israeli militarism in Abya Yala, and continued efforts to articulate BDS campaigns with the struggles of the continent’s anti-racist, labour, environmental, and Indigenous movements.47

However, the pro-Palestine camp in Abya Yala was unable to halt the advance of the Zionist lobby or to respond forcefully to the atrocities committed in this period, such as the repeated attacks against the Freedom Flotillas from 2010 on, the deadly escalation of violence against Palestinians in the West Bank and Al Quds/Jerusalem in 2015 (during the ‘Knife Intifada’), the mass killing and maiming of demonstrators during the Great March of Return protests in Gaza (2018–2019), the annexation announcements and the Abraham Accords (2020), and the 2021 deadly attack on Gaza in response to the ‘Unity Intifada’.

Neither was any serious progress achieved in legitimising the Palestinian cause –and delegitimising Israel– following the succession of reports on Israeli apartheid issued since 2021 by B’Tselem, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and other organisations. In fact, in Abya Yala – as in the rest of the world – the visibility of and interest in the Palestinian cause were at a very low ebb before 7 October 2023. Once again, the message the world was giving the Palestinian people was that they are only taken seriously when they take up arms or when the Israeli regime kills them by the thousands.

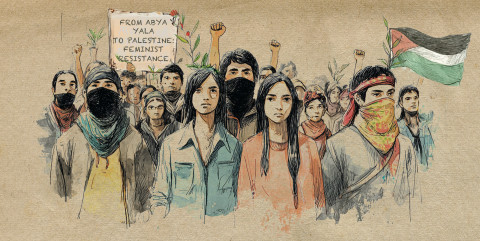

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

How Much has the Genocide Changed Us?

Israel’s televised genocide has now lasted for more than two years, but still only the governments of Bolivia, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Belize have cut off diplomatic ties with Israel, while Chile has withdrawn its military attachés and Colombia has also suspended coal exports. Like all Western governments, the rest have failed to go beyond declarations and continue to repeat the ‘two state’ mantra, as if it were a magic formula that will solve everything. They seem unaware that 145 members of the United Nations have already recognised the State of Palestine and nothing has changed, and that only international isolation and sanctions can force Israel to put an end to the colonial occupation and can make Palestinian self-determination a reality.

At the same time, it is undeniable that since 7 October 2023 some Latin American governments have taken steps in the right direction, although insufficient so far. Nicaragua, Cuba, Colombia, Mexico, Chile, and Brazil have joined the genocide case brought by South Africa before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In addition, of the eight countries that make up the Hague Group, half are from Abya Yala (Cuba, Honduras, Bolivia, and Colombia). This group was launched by the Progressive International in January 2025 with the aim of enforcing the resolutions issued by the International Criminal Court, the ICJ (in particular the Advisory Opinion of 19 July 2024), and the UN General Assembly (A/RES/ES-10/24, of 18 September 2024), which have ordered Member States to take effective measures to end Israel’s impunity.

Furthermore, Colombia (with South Africa) co-chaired the July 2025 Emergency Ministerial Conference on Palestine, which closed with the Bogota Joint Statement, in which 13 countries (5 of them from Abya Yala)48 committed to six measures to prevent the transfer of weapons to Israel, commence an urgent revision of all public contracts with the country, and pursue accountability for its crimes by supporting universal jurisdiction and international law.

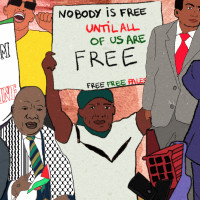

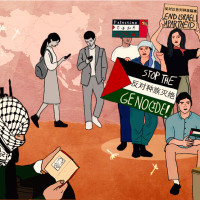

Alongside these shifts at the level of governments, since 7 October popular interest in and sympathy for the Palestinian cause has grown enormously in Abya Yala, like in the rest of the world. Marches, mobilisations, performances, talks, and campaigns have multiplied everywhere.49 In every country, pre-existing solidarity has been enhanced through new collectives, networks, and initiatives – led in particular by young people.50 A significant example is the emergence of new Jewish anti-Zionist groups in the region.51

The Global Feminist Action for Palestine was a powerful initiative that gathered feminist organisations and groups that – responding to a call from their Palestinian peers – agreed to put the genocide and the resistance of Palestinian women at the centre of the 25 November 2023 mobilisations on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, under the slogan ‘From Abya Yala to Palestine: Feminine Resistance’. They organised themselves through networks and virtual groups and drafted a joint manifesto, which was read at the mass marches staged throughout the region. While that level of coordination has been hard to sustain, it is undeniable that the fight against the genocide and in defence of Palestine has now reached feminist, sexual dissidence spaces and beyond. This is evident in the Women’s 8 March mobilisations and in Pride marches.52 Indeed, attempts by Zionist propaganda to co-opt feminist and sexual diversity spaces through a narrative about patriarchal and homophobic Islamism, or lies about sexual violence being used as a weapon of war on 7 October 2023, have been unsuccessful. On the contrary, they have prompted reflections on the incompatibility of feminism and Zionism, or among those who claim to defend the rights of sexual dissidents while committing, justifying, or denying Israel’s apartheid and genocide.

In contrast to these initiatives at the grassroots level, institutional responses have not been up to the challenge. Health, education, and press unions have been slow and belated to speak out against the mass murder of their peers in Gaza, although their responses differ across the region. Similarly, while the labour confederations of the Mercosur countries have condemned the genocide, their limited responses have not been accompanied by a call to suspend the bloc’s free trade agreement with Israel and to end government, corporate, and institutional complicity, nor have they stepped up their solidarity with Palestinian unions. As the Spanish trade union activist Santiago González Vallejo has noted, the general tone has been one of an abundance of solidarity statements but a lack of effective action against Israel.

Nonetheless, after more than two years of mobilisation, the demand to cut diplomatic, commercial, and military ties with Israel is steadily winning support in the region. This coincides with significant growth of the BDS movement, which turned 20 in July 2025. Its historical demands have earned legitimacy thanks to resolutions by the ICJ, the UN General Assembly, and the special mechanisms of the Human Rights Council (led by Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese), as well as the reports concluding that Israel is committing genocide issued by the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel, and by organisations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and B’Tselem, among others.

BDS groups are now present in a dozen countries in Abya Yala, where they are pursuing various campaigns and initiatives. In Colombia, the Tadamun Antimili collective has made significant progress, boosted by the BDS Assembly held when the Hague Group met in Bogotá, and by the broad call of Colombian social movements on the need to join the BDS movement. In Brazil, the movement has managed to link the Palestinian cause with peasant, anti-racist and favelado movements fighting against state violence, and together they are putting pressure on Lula's government to cut diplomatic, commercial and military ties with Israel. In 2024, BDS Brazil and its allies succeeded in getting the government to cancel the purchase of Atmos 2000 howitzers from the Israeli military company Elbit Systems.

Turning to the academic sector in Abya Yala, its response to the scholasticide in Gaza has been uneven. In Bolivia, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, Puerto Rico, and Mexico student encampments have called on universities to end their complicity with Israel; the Mexican collective Academicos con Palestina has furthered academic boycott initiatives; and the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) and El Colegio de México have cut their ties with Israeli universities. In Brazil, the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), the Federal University of Ceará (UFC), and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) have cancelled all their agreements with Israeli universities.53 In Uruguay, the University of the Republic (UdelaR) has called on the government to close its ‘Innovation Office’ in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and announced that it will not participate in any project connected with it. This decision was backed by the country’s sole confederation of workers.54

The Palestine-Latin America Working Group of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) was formed in 2019 ‘to give greater visibility to the Palestinian question and the forms of resistance it has in common with other peoples, through research and conceptual contributions’. It published the Al Zeytun magazine and some specialised dossiers, in addition to including the Palestinian question in some of CLACSO’s regular courses, such as the course on Epistemologies of the South. In the past two years the Working Group has operated more as a space for sharing information on the activities of its members, rather than for coordinating academic boycotts in the region. Within the framework of the Tenth CLACSO Conference (June 2025, Bogotá), the Working Group organised the Palestine, a Global South Cause forum, which included three thematic panels.

Lastly, while the Global Sumud Flotilla was followed closely in Abya Yala, participation by people from the region was limited, due to economic constraints and geographical distance. Only a few countries (Mexico, Brazil, Argentina) were able to send significant delegations, while others (Uruguay, Chile, Colombia) were represented by activists who live or found themselves in Europe at the time.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Pending (and Urgent) Challenges

On 6 October 2023, the Palestinian cause seemed to have been relegated to the margins or even forgotten in Abya Yala, as in the rest of the world. For example, the 75th anniversary of the Nakba, on 15 May 2023, went practically unnoticed. But everything changed on 7 October when the Palestinian resistance tore down the prison walls of Gaza to remind us that the false pacification the empire proposes for Western Asia will never be feasible as long as the Palestinian people are ignored. Indomitable Gaza, which has always been the cradle of Palestinian rebellion, is paying a very steep price for writing the bloodiest, but perhaps decisive, chapter of its struggle for liberation. While the Zionist extermination project has never been so close to achieving its goal of completing the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, in over a century of resistance the Palestinian cause has never received such global support, sustained throughout more than two years by the collective outrage at the complicity of the powerful in the genocide, including in Abya Yala.

The peoples of the world, especially the peoples of the Global South, must now take on the challenge of going beyond the ‘UN consensus’ on the partition of Palestine, which is the product of a global system created in 1945 before the massive decolonisation processes of the twentieth century, and currently in crisis. This does not in any way entail dismissing the architecture of international law. On the contrary, it needs to be defended because it is a source of moral and legal legitimacy for claiming the rights of the Palestinian people and of oppressed peoples everywhere. But it also means recognising that the UN consensus is a straitjacket that prevents us seeing things as they really are and imagining more just, realistic, and creative options, including moving beyond the Western model of the nation state.

In Abya Yala, this task involves addressing a number of challenges, some of which are outlined below –recognising the diversity of stakeholders and responsibilities at play–.

Overcoming the epistemic trap

UN Resolutions 181 (1947) and 242 (1967), as well as the Oslo paradigm, view the Palestinian question as a conflict between two peoples. However, as historian Jorge Ramos Tolosa notes,55 it is increasingly understood as a typical case of settler colonialism, the premise of which is the elimination of the native population. This is key for understanding that the origin of the problem is Zionism, which is a colonialist, racist, and supremacist ideology and political project born in Europe in the late nineteenth century, when nationalist projects were prevalent.

It must be asked: in what other decolonisation or liberation process of the past century (be it Algeria, Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique, or South Africa) was it proposed to divide the territory so as to give one part of it – the largest part – to the colonisers and the other to the native or colonised population? Even if states cannot – or are not willing to – go beyond the partition model and its unfair and illegitimate ‘1967 borders’,56 the peoples of the South must fight alongside the Palestinian people for the liberation of the whole of Palestine and its entire population; not just the 5.5 million living in the territories occupied in 1967 (the West Bank, Gaza, Jerusalem), but also the nearly 2 million more who live under apartheid in the ‘1948 territories’, and in particular the 6 to 7 million (half of all Palestinians) who live miserably and without rights in refugee camps in neighbouring countries or are exiled around the world, and whose right to return (now applying to a fourth generation of refugees and exiles) has been violated since 1948 and ignored in all negotiations based on the Oslo scheme.

This also entails understanding that the recognition of the State of Palestine without the liberation of its people is an illusion. Ultimately, it entails reclaiming the paradigm that should never have been lost sight of: the decolonisation of Palestine and the dismantling of the apartheid regime; or, as Hamza Hamouchene puts it, ‘passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle’. Overcoming the Oslo paradigm requires reaffirming that the Palestinian cause is a national, anti-imperialist, and anti-fascist liberation struggle, and that the Palestinian people has the legitimate right to defend themselves and to resist colonial domination and apartheid by all possible means (including armed struggle),57 and to connect their struggle with other anti-racist and anti-colonial struggles in Abya Yala, such as the often overlooked struggle of the Haitian people.58

Palestine in formal and popular education

The great interest in learning about the Palestinian question that has recently emerged in Abya Yala poses new challenges, not only for the production of knowledge, but also, and especially, for socialising and democratising that knowledge. It is necessary to expand the new spaces that have opened up at the level of civil society and formal education. This also applies to universities, where there is a very diverse reality in Abya Yala with regard to studies on Palestine, the Levant and Western Asia.

One experience that could serve as a model here is the ‘cátedras libres Edward Said’ (open chairs) that exist in several Argentinian universities.59 As they operate under the outreach departments of university schools (usually the school of philosophy and literature), these chairs combine academic research and teaching with community outreach through in-person or virtual courses in teacher training centres and social organisations. The extensive teaching experience of these chairs could be harnessed to train teachers and institutions at the secondary and higher education levels in other places that lack such specialised training.

Another constant challenge is connecting Palestine studies with decolonial studies, Indigenous studies, and critical studies on racism. As observed by Gabriel Sivinian, coordinator of the Edward Said Chair of the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), post-colonial and decolonial studies should focus on the Palestinian question, given that the field was inspired to a large extent by Said’s work: ‘Taking up Said and not taking up the question of Palestine is a somewhat peculiar epistemic operation. However, while some decolonial intellectuals have written about it, generally speaking that is not the rule.’60

Breaking the Babel curse

It is as much the language barrier as it is geography that separates people in Abya Yala from Palestine and Palestinians, since the region is neither Anglophone nor Arabic-speaking. Most Palestinian advocacy and networking efforts outside the Arab world have focused on Europe, North America, and the English-speaking South, and have not prioritised forging relations with Abya Yala (with few exceptions, such as Stop the Wall, the BDS movement, and the Palestine Institute for Public Diplomacy). In this context, it is important to start investing in translation efforts (with financial support from the North) in both Abya Yala and Palestine, to overcome the language barrier. This can help to:

- Maintain a direct and fluid dialogue among activists in Abya Yala and Palestine, through virtual or in-person exchanges, with the aim of learning about their respective realities and the experiences they have in common61

- Make accessible in Abya Yala the abundant quality information and analytical resources on the Palestinian question that exist in English and Arabic,62 including the critical and defiant voices of the new Palestinian generation, who often write in English, but whose writings are rarely translated into Spanish or Portuguese.63

- Expand the horizon to build solidarity networks and global interconnections that allow for a genuine exchange and mutual learning of knowledge, practices, experiences and reflections in order to build South-South solidarity that is not mediated by the North.64

Feet firmly planted on the (Palestinian) ground

First-hand knowledge of the Palestinian reality and meeting with its people in their own land is irreplaceable. We know what the challenge of travelling to Palestine entails for people in Abya Yala, where there are no subsidies for this purpose or savings capacity, and where activists – in contrast to those in the northern hemisphere – usually work for different causes entirely on a voluntary basis, often facing precarious employment and/or holding several jobs.65

In this context, there is a need to explore collective and solidarity-based ways for people from Abya Yala to travel to Palestine. Proof that such an approach is possible can be found in the region’s long tradition of sending solidarity brigades to Cuba, Nicaragua, Chiapas, and other places to help with sugarcane, coffee, or orange harvests, and to offer international support to communities threatened by militarisation. These brigades are similar to the yearly arrival of solidarity activists from around the world to help out with the olive harvest in Palestine – a critical period for the livelihoods of families and communities, and therefore one that Israeli settlers take advantage of in order to intensify their violence against Palestinians.

Engaging first-hand with Palestinian reality can take different forms, such as:

- Sending delegations to learn about and support projects in Palestinian communities, such as planting olive trees and harvesting olives, as Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) and Friends of the Earth have done.

- Arranging prolonged stays (backed by international accompaniment and solidarity programmes) in communities under threat from Israeli soldier and settler violence.

- Various modes of exchange and mutual learning, such as artistic residences; internships in cultural, academic, or human rights institutions; technical cooperation in affected communities; voluntary work in refugee camps, etc.

Knowing more to better understand Palestinian politics

At the present conjuncture, when the question of Palestinian representation and legitimacy is more contentious than ever66, it is essential for people involved in solidarity activism in Abya Yala to expand relations with the various political actors beyond the PA embassies. It is also necessary to learn about the history of the Palestinian political process, its different periods, actors and positions, especially before and after Oslo and the creation of the PA, and about the present dynamics as well.67 Equally important is analysing opinion polls conducted across Palestinian society, to see how Palestinians’ political preferences and the legitimacy of each actor has evolved in a society that has not had an election in 20 years (except at the local level). Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that the official representation granted by the UN to the PA led by Mahmoud Abbas is the result of Western powers refusing to recognise Hamas’s victory in the 2006 elections.

There is also a need to reach out to the plurality of voices from Palestinian society: leftwing parties, trade unions, human rights groups, rural organisations, feminists, environmentalists, queer people, journalists, artists, intellectuals, and (especially) young people, who are often not tied to traditional affiliations and have their own ways of doing politics.

Recognising the ‘sacredness’ of the land

This deliberately provocative title is an invitation to overcome the anti-religious prejudice – prevalent among much of the agnostic left– which prevents it from understanding the spirituality rooted in most of the Palestinian people. This does not entail erroneously interpreting the Palestinian question as a conflict rooted in religion. But one cannot ignore the weight of these subjective aspects in a land considered sacred by the three monotheistic religions (as is evident touring the Old City of Al Quds). How else can we understand the powerful symbolic value that the Haram al-Sharif compound has for the Palestinian people, which provokes intifadas and rocket launches from Gaza when it is violated?

Taking the religious dimension into consideration also helps us to understand the messianic ideology of the fanatical settler movement currently in power in Israel, which seeks to build the Third Temple on the ruins of the Al Aqsa mosque, as well as its ideological motivations for appropriating the most ‘sacred’ part of the Palestinian territory: the West Bank, which it calls by the Biblical name of ‘Judea and Samaria’.

It is also not enough to say that the Zionist project has instrumentalised religion to justify of the conquest and annexation of Palestine, because the religious dimension is present in the everyday life of the Palestinian people, in their worldview, in their resilience, in the motivation behind their struggle, and in their certainty of the final victory. How often, faced with the demolition of their homes, the destruction of their olive groves, the slaughtering of their livestock, the execution or imprisonment of their loved ones, when asked where they find the strength to resist, they answer raising their eyes and hands ‘from Allah’.

Faith is at the root of Palestinians’ tenacious hope and their spirit of sumud, which is so difficult to translate. It is what explains their age-old patience and their century-long resistance to Zionism. We cannot fully understand the last 26 months in Gaza without understanding this inner strength. As the testaments of murdered journalists such as Hossam Shabat and Anas Al-Sharif show, this faith is an inner force that mobilises among many Palestinians the conviction that martyrdom is the seed of liberation.68

Another implication of the refusal to consider the religious dimension of the Palestinian struggle is the prejudice against Islamist resistance, which often goes hand in hand with Islamophobia. Over the past two years this issue has divided the Left in the West and triggered heated debates. This ideological rigidity prevents from listening to Palestinian intellectuals69 when they explain that the fundamental cleavage for them is not between secular and religious, Left and Right, conservatives and progressives, but between those who resist and those who collaborate. And that in Palestine, people support those who resist, whether nationalist, Marxist, or Islamist.70

The absence of the religious dimension in most of the works and publications on the Palestine question has had another negative consequence for its cause in Abya Yala. In this region where Christian culture is predominant, there is little awareness of the existence of indigenous Christian people and communities who are an integral part of the Palestinian people, who have played prominent roles in the century-long resistance to the Zionist project, and who have coexisted peacefully with the Muslim majority.71 The existence of these Palestinian Christians is inconvenient for Zionist propagandists because it overturns the Zionist narrative that Israel is defending Western Judeo-Christian civilisation against violent Islam; because it opens up Western churches to severe criticism over their silence or complicity with Israel; and because it exposes Christian Zionism as a ‘theology of the empire’, which must be countered with a decolonial and liberation theology based on two hermeneutic keys: the land and its native people.72

Embracing the BDS movement

In 2017, Omar Barghouti, co-founder of the BDS movement, told a group of activists in Madrid: ‘We do not have time anymore for symbolic solidarity’. Eight years later – two of which have witnessed an accelerated genocide – taking the qualitative next step to effective solidarity is more urgent than ever: only boycotts, divestment, sanctions, and international isolation will make the price of maintaining the status quo unsustainable for the Zionist regime. This entails carrying out BDS campaigns on multiple fronts and connecting them regionally and internationally to exert sustained and effective pressure.

Opting for this path involves burying for good the false ‘peace process’ paradigm. It is not possible for Palestinians to negotiate with Israel, at least not in the current conditions, not only because of the enormous asymmetry between Israel and the Palestinians, but also because of its long track record of negotiating in bad faith, murdering Palestinian negotiators, refusing to yield an inch, and failing to honour the agreements it has signed.73 The ‘Jewish state’ will not allow the existence of a Palestinian state anywhere in ‘Eretz Israel’ (the Land of Israel). Even if Israel’s current fascist government is replaced by a more moderate one in the future, the only change will be in appearance.74 That is why the path to organised solidarity is that of the South African people: without the mass sanctions and the international pressure and isolation that turned it into a pariah state, the racist South African regime would not have agreed to free Nelson Mandela and to dismantle the Apartheid system.

Andressa Oliveira Soares’s prescription for Palestine solidarity in Brazil applies throughout Abya Yala: ‘The path forward requires further intersectional organising; continued work with trade unions, student movements, and environmental and defence-of-territory groups; persistent pressure on the government; increased regional coordination; and a public education strategy that dismantles Israeli propaganda.’75

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

History is Not Over Yet

The Palestinian cause currently faces its most uncertain moment following a new betrayal by the ‘international community’: the ratification by the UN of the imperial-colonial plan for Gaza devised by the US and Israel. But, once again, the Palestinian people have confirmed that their liberation and self-determination will not come from the decadent and increasingly illegitimate international system. Instead, they know that justice, reason, and history are on their side, while the Zionist project has no future. Above all, over these past two years they have learned that they have the support of the peoples of the world.

Any analysis or forecast that does not take into account this factor, as well as the enormous moral and spiritual reserves that the Palestinian people have demonstrated in their resistance throughout the more than century-long colonial and genocidal Zionist project, will be flawed. Those of us who have seen up close the indomitable spirit of the Palestinian people despite the repeated betrayals to which they have been subjected, who have looked into their eyes, have heard them, laughed with them and drunk maramiya (sage) tea with them under their olive trees or amidst their demolished homes, we know that they are an invincible people who will continue to resist and who will never raise the white flag of surrender – and we also know that losing hope is a luxury the Palestinians cannot afford. What they need from us, the people of the world, is a commitment that we will never abandon them: we will stand with them until Palestine is free.

Let two young Palestinian voices say it in their own words:

Qassam Muaddi (journalist and writer, Ramallah) – ‘How this ends will depend on the rest of the world. How much longer are the powerful in the West going to cling to this Zionist colonial project? How much longer are they going to insist that the Palestinian people have no place in the world? Palestine will be free. The only question is when it will be free. […] That also depends on the rest of the world and not just on us, who have already given our all. […] I hope the awareness that has been shown in the streets is real, and that the peoples of the world will not let themselves be fooled as they did with Oslo. I hope that the solidarity that has erupted everywhere is irreversible, and that the change that was triggered as a result of the genocide will not stop. Not just for Palestine, but for all of humanity.’76

Israa Mansour (writer and student, Gaza) – ‘We are daughters and sons of this land; we learned that resisting is not an option, but our destiny. […] Hope in Gaza is not a matter of choice, it is what keeps us alive every day. It is believing that this land, despite all the destruction, will flourish again one day. That the planes will leave, that the sound of explosions will be a mere distant memory that we will tell our grandchildren when we recount the history of resistance. […] Gaza will remain, even if all its houses are turned into rubble. It will remain in our hearts, in our blood, in each word we have written. We were not made to be defeated; we were made to be eternal witnesses of the strength of human beings, a strength greater than war. Close this page now, but remember: history is not over yet.’77

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of TNI.

Palestine Liberation series

View series-

El contexto de Palestina Israel, los Estados del Golfo y el poder de los Estados Unidos en Oriente Medio

Fecha de publicación:

-

Actitudes y solidaridad de África con Palestina De la década de 1940 al genocidio de Israel en Gaza

Fecha de publicación:

-

Al fallarle a la revolución sudanesa, le fallamos a Palestina Lecciones de los vínculos entre Sudán y Palestina en materia de política, medios de comunicación y organización

Fecha de publicación:

-

Fantasías de sostenibilidad/realidades genocidas Palestina contra un mundo de apartheid ecológico

Fecha de publicación:

-

Vietnam, Argelia y Palestina Pasar la antorcha de la lucha anticolonial

Fecha de publicación:

-

Del antiimperialismo internacional a los guerreros diente de león La solidaridad de China con Palestina de 1950 a 2024

Fecha de publicación:

-

El circo de la complicidad académica Un espectáculo tragicómico de evasión en el escenario mundial del genocidio

Fecha de publicación:

-

India, Israel y Palestina Las nuevas ecuaciones exigen nuevas solidaridades

Fecha de publicación: -

Ecocidio, imperialismo y la liberación de Palestina

Fecha de publicación:

-

De las favelas y el Brasil rural a Gaza Cómo el militarismo y el greenwashing determinan las relaciones, la resistencia y la solidaridad con Palestina en Brasil

Fecha de publicación: