De las favelas y el Brasil rural a Gaza Cómo el militarismo y el greenwashing determinan las relaciones, la resistencia y la solidaridad con Palestina en Brasil

Los movimientos de solidaridad de Brasil han apoyado durante mucho tiempo a Palestina, pero los lazos económicos y militares con Israel se profundizan cada vez más. Mientras Brasil se prepara para albergar la COP30, las campañas de base están exponiendo los vínculos entre el militarismo israelí y la desigualdad interna, el agronegocio y la violencia estatal. Este momento ofrece una oportunidad clave para fortalecer las iniciativas de Boicot, Desinversión y Sanciones (BDS).

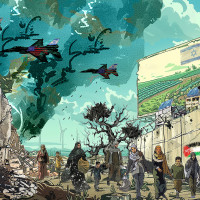

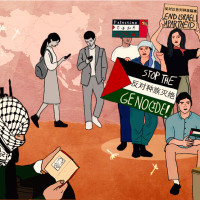

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

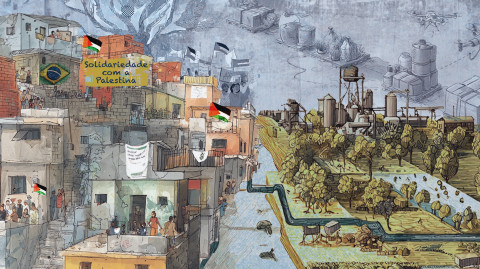

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Las relaciones militares, económicas y diplomáticas de Brasil con Israel

Desde mediados del siglo XX, la relación de Brasil con Israel ha combinado la alineación simbólica con la cooperación pragmática. En 1947, el diplomático brasileño Oswaldo Aranha, como presidente de la Asamblea General de la ONU, desempeñó un papel procedimental y político crucial al impulsar el Plan de Partición para Palestina (Resolución 181 de la ONU). Testimonios de la época y reconstrucciones posteriores atribuyen a Aranha el haber aplazado la votación para consolidar una mayoría de dos tercios a favor del plan, y de haber ejercido presión activamente sobre las delegaciones, acciones por las cuales recibió honores públicos en Israel en décadas posteriores (JTA, 2017). Su relieve en la ONU dejó como huella una asociación temprana entre la diplomacia brasileña y la legitimación internacional del Estado de Israel.

Durante los primeros años de la década de 1960, con el Gobierno de izquierda del presidente brasileño João Goulart, las relaciones bilaterales fueron cordiales pero utilitarias, caracterizadas menos por la convergencia ideológica que por cálculos multilaterales y el deseo de cooperación técnica. La dictadura militar (1964-1985) inauguró una aproximación más transparente en seguridad y de índole tecnocientífica. Informes de investigación citan materiales de archivo que indican la existencia de relaciones complacientes entre Israel y la junta brasileña, incluyendo la venta de armas, el intercambio de experiencia militar y una cooperación nuclear temprana. Un acuerdo entre ambos países se habría firmado el 10 de agosto de 1964, apenas cuatro meses después del golpe, al que le siguieron otros acuerdos en 1966, 1967 y 1974 (Mack, 2018). Si bien estas fuentes no demuestran participación u orquestación israelí alguna en el golpe mismo, indican una rápida alineación posterior al golpe entre los dos países, basada principalmente en intereses compartidos relacionados con la seguridad y el desarrollo de capacidades nucleares, coherente con la búsqueda en general de tecnologías estratégicas por parte de la dictadura. El resultado de esa alineación fue un patrón en el que el régimen de Brasil aprovechó los vínculos israelíes en defensa y ciencia mientras, a la vez, profundizaba una asociación nuclear más amplia con Alemania Occidental (1975), y mantenía un programa nuclear paralelo y poco transparente que se extendió después de la dictadura militar hasta principios de la década de 1990 (Arms Control Association, 2006; World Nuclear Association, 2025).

Ya en democracia (a partir de 1985), Brasil ha alternado entre el apoyo simbólico a los derechos palestinos (por ejemplo, el reconocimiento y posicionamiento diplomático) y la continuidad de vínculos pragmáticos con Israel en materia de comercio, seguridad y tecnología. Una perspectiva de larga duración revela así una doble vía: el papel fundacional brasileño en la legitimación internacional del Estado de Israel en 1947 y, décadas después, la cooperación posterior al golpe que incorporó la experiencia israelí a la modernización autoritaria de Brasil.

A pesar de ese panorama general, las relaciones diplomáticas entre Brasil e Israel han variado considerablemente, según la administración en el poder, aunque en los hechos esas relaciones bajaron de categoría solo muy recientemente. Por ejemplo, durante la primera década del siglo XXI, América Latina en su conjunto fue testigo de una destacada reconfiguración de su orientación de política exterior hacia el "problema" israelí-palestino. Este cambio fue influido en gran medida por el ascenso electoral de Gobiernos de izquierda y centroizquierda en América Latina, en lo que se denominó "marea rosa", que supuso una reacción contra el Consenso de Washington (Lucena, 2022), así como por la consolidación de las relaciones económicas y políticas Sur-Sur, con el surgimiento de los BRICS y la "política exterior activa y firme" de Brasil. Estos hechos alentaron intentos de afianzar una mayor autonomía frente a Estados Unidos y la diversificación de las alianzas internacionales. En este contexto, el compromiso con la causa palestina se convirtió, para muchos Gobiernos latinoamericanos, en un instrumento estratégico de posicionamiento internacional (Baeza, 2012).

Sin embargo, a pesar de esta tendencia general hacia un mayor apoyo a los derechos palestinos, la mayoría de los Estados latinoamericanos –particularmente las economías más grandes, como Brasil, Argentina y México– continuaron determinando sus posiciones en función del equilibrio. Las expresiones de solidaridad con Palestina con frecuencia se acompañaban de afirmaciones del derecho de Israel a la seguridad, lo que revelaba una estrategia dual de reconocimiento simbólico y diplomacia pragmática (Baeza, 2012). Por ejemplo, la ola de reconocimientos del Estado de Palestina entre diciembre de 2010 y marzo de 2011, que representó una tendencia regional hacia el reconocimiento formal de la soberanía palestina, se expresó a menudo con un discurso que enfatizaba el "equilibrio" y la promoción de la "paz", en lugar de acompañarse de sanciones abiertas o críticas a Israel (Baeza, 2012).

El Brasil del presidente Lula da Silva fue un ejemplo particularmente notable de este enfoque "equilibrado". Como potencia ascendente con ambiciones de influir en el mundo, durante la primera y segunda administración de Lula (2003-2010) Brasil buscó proyectar un liderazgo diplomático en relación con Oriente Medio, y su Gobierno demostró una sensibilidad sin precedentes hacia las preocupaciones palestinas, que culminó con el reconocimiento brasileño del Estado de Palestina en diciembre de 2010. Sin embargo, mientras Venezuela y Bolivia optaron por una confrontación abierta mediante la suspensión de relaciones con Israel en 2009, el Brasil de Lula lideró a la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos en la búsqueda de una política que simultáneamente avanzaba en el reconocimiento palestino y preservaba los vínculos bilaterales con Israel (Baeza, 2012).

Esta política se interrumpió durante la presidencia de Jair Bolsonaro, cuando Brasil se alineó abiertamente con Israel: abrió una oficina comercial en Jerusalén en 2019, consideró trasladar su embajada de Tel Aviv a Jerusalén (aunque finalmente no lo hizo) y se incorporó al Israel Allies Caucus.5 Esta postura reforzó la alineación ideológica de Brasil con el evangelismo conservador y las élites empresariales (Huberman, 2024).

Durante el tercer mandato de Lula, que comenzó en 2023, Brasil volvió a su política anterior. En la apertura de la Asamblea General de la ONU de ese año, Lula habló sobre la importancia que tiene resolver "la cuestión palestina" y el "reconocimiento de un Estado palestino viable e independiente", pero Brasil mantuvo las relaciones diplomáticas con Israel y se resistió a reconocerlo como un régimen de apartheid. Sin embargo, tras el comienzo del genocidio en octubre de 2023, el Gobierno de Lula redobló sus críticas a las operaciones militares israelíes. En febrero de 2024, en la cumbre de la Unión Africana celebrada en Adís Abeba, Lula comparó la conducta israelí en Gaza con el genocidio nazi. Israel respondió declarando a Lula persona non grata, y Brasil rápidamente retiró a su embajador de Israel y degradó las relaciones diplomáticas al negarse (hasta la actualidad) a acreditar al embajador israelí en Brasilia (MercoPress, 2023). Las declaraciones oficiales desde el inicio del genocidio subrayaron el continuo apoyo de Brasil al Estado palestino y al derecho internacional, y reforzaron las críticas al Gobierno de Netanyahu. No obstante, también buscan separar al actual Gobierno israelí del propio Estado de Israel, y Brasil mantuvo en gran medida intactos los lazos comerciales y militares.

Cabe señalar que, a pesar del genocidio, los vínculos económicos entre Brasil e Israel, con algunas excepciones, siguen el patrón instalado en décadas anteriores. Desde principios de la década de 2000, Brasil e Israel profundizaron sus relaciones económicas. En 2007, durante la presidencia de Lula, Brasil lideró la firma de un tratado de libre comercio (TLC) entre el Mercosur6 e Israel. La exposición de motivos del decreto que aprobó el TLC señala que en 2007 el intercambio comercial entre Brasil e Israel había alcanzado los mil millones de reales (alrededor de 200 millones de dólares estadounidenses), con un crecimiento del 30 por ciento respecto a 2006 (Brasil, Congresso Nacional, 2009). En ese momento, los principales productos que Brasil exportaba a Israel eran carne, soja y aditivos para combustible, mientras que las principales importaciones eran "fertilizantes y agroquímicos" (Brasil, Congresso Nacional, 2009).

Los sectores de la agroindustria y del petróleo son los mayores beneficiarios de las relaciones comerciales entre Brasil e Israel. Las cifras demuestran que ambos sectores desempeñan una función clave en el sostenimiento de las relaciones entre Brasil e Israel, más allá de quién esté al mando. Al mismo tiempo, estos sectores también son responsables de numerosas violaciones de los derechos humanos y ambientales de las poblaciones del sector rural brasileño (Articulação para o Monitoramento dos Direitos Humanos no Brasil [AMDH], 2025). Además, estos sectores también son grandes simpatizantes de políticos de ultraderecha en Brasil.

La alineación entre los sectores de la agroindustria y el petróleo, los políticos brasileños de ultraderecha e Israel se revela en datos recientes que muestran que, entre 2019 y 2022 (el período del Gobierno de Bolsonaro), las exportaciones a Israel en esos sectores crecieron año tras año, al pasar de 371 millones de dólares a 1 800 millones de dólares (MDIC, s.f.). En 2023, el monto disminuyó a unos 662 millones de dólares,7 de los cuales el 21 por ciento correspondió a petróleo crudo, el 19 por ciento a carne vacuna y el 18 por ciento a soja (Nakamura, 2024). Sin embargo, incluso después del regreso de Lula, las exportaciones de petróleo en 2024 convirtieron a Brasil en uno de los mayores proveedores de crudo de Israel (Lakhani y Niranjan, 2024), responsable del 9 por ciento del total que Israel recibió ese año, sin contar los productos derivados.

En lo que respecta a los productos israelíes que importa Brasil, predominan los fertilizantes y la tecnología agrícola, siendo Israel uno de los mayores proveedores de Brasil de estos productos (Pligher, 2023). En 2023, Brasil importó aproximadamente 1 400 millones de dólares de estos productos, de los cuales el 45 por ciento fueron fertilizantes y el 11 por ciento pesticidas, principalmente de las empresas israelíes Haifa Group y Adama (Nakamura, 2024). Además de los agroquímicos, Brasil también importa tecnología agrícola israelí, como drones que se utilizan para operar sistemas de fertilización y riego. Esta tecnología procede sobre todo de Haifa Group, Adama y Netafim.

Cabe destacar aquí el papel que estas y otras empresas de agrotecnología desempeñan en el greenwashing o ecoblanqueo israelí. Este término refiere al uso estratégico que hace Israel del lenguaje y el discurso ambiental para ocultar o legitimar sus prácticas de colonialismo mediante los asentamientos, la ocupación y el despojo (Who Profits Research Center, 2020). En el relato de ecoblanqueo que promueven estas empresas, se presenta a Israel como un líder mundial en sostenibilidad e innovación, mientras se oculta deliberadamente el daño ecológico real y las violaciones sistemáticas de los derechos humanos que estas empresas y el Estado israelí perpetran contra la población palestina y su medio ambiente (Who Profits Research Center, 2024). En particular, el sector de la agroindustria israelí propaga el mito sionista de que los colonos sionistas en Palestina “hacen florecer el desierto”, con lo que comercializan sus tecnologías de riego y agricultura desértica como soluciones globales al cambio climático y la inseguridad alimentaria, a la vez que borran el desplazamiento histórico de los agricultores palestinos y la destrucción ecológica que provocan la expansión de los asentamientos de colonos (Who Profits Research Center, 2020).

Las mencionadas Adama y Netafim, con sus considerables exportaciones a Brasil, son dos de las mayores empresas de la agroindustria israelí y ejercen un papel central en las estrategias de greenwashing del país. Netafim, muy reconocida por ser pionera en tecnologías de riego por goteo, se comercializa como proveedora de soluciones para la escasez mundial de agua y los desafíos climáticos. La publicidad de su marca pone énfasis en la eficiencia, la sostenibilidad y la seguridad alimentaria, y proyecta una imagen de responsabilidad ambiental. Sin embargo, las operaciones de la empresa en la Palestina ocupada revelan una contradicción flagrante. Netafim proporciona sistemas de riego a los asentamientos israelíes ilegales en Cisjordania. Al exhibir sus tecnologías como innovaciones ambientalmente sostenibles, Netafim oculta la realidad material del despojo y la redistribución de los recursos hídricos lejos de las comunidades palestinas.

En este sentido, su reputación internacional como innovadora ambiental funciona como un escudo contra el examen de su complicidad en la expansión de los asentamientos de colonos (Who Profits Research Center, 2020). Adama, una de las principales productoras mundiales de agroquímicos, también está implicada en dinámicas de greenwashing. La empresa promociona su cartera de productos de protección de cultivos, fertilizantes y sistemas de manejo de plagas como herramientas para una agricultura sostenible que mejora los rendimientos y minimiza el daño ambiental. Pero las actividades de Adama están estrechamente vinculadas al modelo de agroindustria de Israel, que se basa en la apropiación de tierras, el monocultivo intensivo y la marginación de las prácticas agrícolas palestinas (Who Profits Research Center, 2020). Además, la empresa se beneficia de la estrategia internacional de marca del Estado israelí, que comercializa la agroindustria israelí como una forma de agricultura climáticamente inteligente que puede exportarse a todo el mundo, lo que afecta especialmente a las comunidades del Sur Global (GRAIN, 2022). Esta narrativa de sostenibilidad oculta en los hechos los costos ecológicos del uso intensivo de productos químicos, la degradación del suelo y el desplazamiento de los sistemas agrícolas locales.

En conjunto, Netafim y Adama ejemplifican la manera en que las empresas de la agroindustria israelí utilizan la promoción ecológica de sus marcas para naturalizar y legitimar las estructuras de despojo y expansión colonial. Su reputación mundial como pioneras en la agricultura sostenible ayuda a integrar a Israel a las agendas internacionales de desarrollo, las estrategias de adaptación climática y los programas de seguridad alimentaria, incluso en espacios como la COP (GRAIN, 2022).

Otro ejemplo conocido del greenwashing israelí es la empresa estatal Mekorot, que exporta su experiencia en desalinización y riego, mientras participa simultáneamente en lo que se ha calificado de apartheid hídrico: el desvío de recursos hídricos palestinos hacia los asentamientos israelíes, la restricción del acceso palestino al agua limpia y el uso de la escasez del agua como una forma de control político (PENGON – Palestinian Environmental NGOs Network, 2021). Aunque gracias a las campañas en su contra (analizadas más adelante) Mekorot no logró hasta la fecha ingresar al mercado brasileño, la empresa tiene una fuerte presencia en otras partes de América Latina y África (PENGON – Palestinian Environmental NGOs Network, 2024).

La estrategia de “marca” de Israel no se limita solo al greenwashing: también implica, de manera aún más destacada, al sector militar-industrial. Si bien no hay evidencia del uso militar o represivo de esta tecnología específica en Brasil, esta sirve a la agroindustria en el país, la cual somete a los pequeños productores, campesinos, comunidades tradicionales y pueblos indígenas, incluso mediante el despojo, la contaminación por pesticidas y fertilizantes, y hasta la violencia física y psicológica (Articulação para o Monitoramento dos Direitos Humanos no Brasil [AMDH], 2025). Además, la compra de estos productos de doble uso, como los drones, integra aún más las tecnologías militares israelíes a la economía verde internacional, lo que a su vez profundiza la normalización de la industria de armamentos israelí. Por eso es tan importante imponerle un embargo total a Israel, y no solo a determinados equipos militares israelíes.

Los vínculos de Brasil con el complejo militar-industrial israelí se caracterizan por la importación y la exportación, así como por la inversión de empresas militares israelíes en el sector militar brasileño. Con respecto a lo primero, Brasil aumentó sus importaciones de armas israelíes entre 2010 y 2019, al recibir aviones, drones, misiles y sistemas de mando. Aunque los datos sobre compras militares no son fáciles de encontrar, las cifras oficiales indican que en 2024 Brasil gastó al menos 167 millones de dólares en maquinaria militar, armas y municiones israelíes. La cantidad real probablemente sea mucho mayor, ya que estas cifras no incluyen las compras por parte de los estados y municipios dentro de Brasil, porque muchos de los contratos son secretos y los equipos de doble uso se registran en otras categorías (Trading Economics, 2025). No obstante, incluso según estas cifras oficiales, la "maquinaria militar, reactores nucleares y calderas" fue en importancia la tercera categoría de compras a Israel, después de los agroquímicos y los productos plásticos.

Cabe señalar aquí que la cantidad de productos militar-industriales que Brasil importó de Israel habría sido aún mayor en 2024 de no ser por la presión popular contra este tipo de comercio. En 2024, en pleno genocidio y después de que el presidente Lula reconociera que el mismo estaba ocurriendo, el ejército brasileño comenzó a negociar la compra de 36 obuses autopropulsados ATMOS por un valor de entre 150 y 200 millones de dólares a Elbit Systems, una de las más importantes (si no la más importante) empresas israelíes productoras y exportadoras de tecnología militar (Azulay, 2024). Esto ocurrió a pesar de la creciente tensión política en Brasil en torno al tema, ya que la sociedad civil y sus aliados presionaban para que se aprobara el embargo y las sanciones contra Israel. Finalmente, la campaña contra las importaciones de armas israelíes fue cubierta por los principales medios de comunicación y el Gobierno se retiró del contrato propuesto con Elbit antes de su firma a finales de 2024.

El comercio de armas entre Brasil e Israel no es una calle de un solo sentido: Brasil también exporta al sector militar israelí. Produce suministros para las mayores industrias de Israel, y las empresas brasileñas suelen tener vínculos financieros y de propiedad con empresas de armas israelíes. Por ejemplo, AEL Sistemas, un fabricante militar ubicado en Porto Alegre, en el sur de Brasil, es actualmente una subsidiaria de Elbit Systems (AEL Sistemas, 2025). AEL produce equipos de defensa brasileños utilizando tecnología israelí, con el apoyo del Gobierno federal y otros organismos públicos, y exporta partes militares a Israel (Brasil de Fato, 2023a). Elbit se convirtió en un socio más fuerte del sector militar brasileño a través de otra subsidiaria conjunta, Ares Aeroespacial e Defesa, en el estado de Río de Janeiro (Ares, 2019), que a partir de 2017 fabrica estaciones de armas teledirigidas para el ejército brasileño con tecnología de Elbit. (Azulay, 2024).

Otros sectores de la industria brasileña también tienen vínculos con el sector militar israelí. En 2025, periodistas y movimientos sociales de Brasil denunciaron que acero brasileño se estaba exportando a Israeli Military Industries (IMI), una empresa israelí vinculada a Elbit, para ser utilizado en la fabricación de armas (The Intercept Brasil, 2025). Grupos de solidaridad difundieron documentos de embarque que indicaban el envío previsto de entre 56 y 60 toneladas de barras de acero del Puerto de Santos hacia Haifa, a principios de septiembre de 2025, catalogadas como insumos de “doble uso” con su posible incorporación posterior en la cadena de suministro de la industria militar israelí (Chade, 2025). Las revelaciones generaron protestas en Santos y Río de Janeiro y reclamos de una intervención administrativa para detener el envío (incluidas acciones por plataformas mediáticas y sindicales en la costa de San Pablo), mientras que la prensa destacaba que el acero integraba la lista de las 10 principales exportaciones de Brasil a Israel en 2024, una tendencia que se mantuvo en 2025 (Sindipetro-LP, 2025).

El petróleo es otra exportación relevante de Brasil al sector militar israelí. Como ya se señaló, una investigación de 2024 reveló que Brasil aportó aproximadamente el 9 por ciento del total de crudo suministrado a Israel entre octubre de 2023 y julio de 2024, incluidos buques tanque que partieron después del fallo de la Corte Internacional de Justicia sobre genocidio en febrero de 2024 (Lakhani y Niranjan, 2024). Durante el Gobierno de Bolsonaro (2019-2022), las exportaciones de petróleo a Israel crecieron y alcanzaron un pico de 1070 millones de dólares en 2022 (Trading Economics, 2025), pero incluso durante la presidencia de Lula, los envíos de petróleo a Israel se mantienen en gran medida. Según la Agencia Nacional del Petróleo de Brasil (ANP), esas exportaciones crecieron un 51 por ciento en 2024 frente a 2023. Las principales empresas involucradas son Shell y Petrobrás, la petrolera estatal brasileña (Forgerini, 2025).

Para las redes de solidaridad con Palestina y los movimientos sociales brasileños, estos flujos de petróleo se convirtieron en un punto focal de campaña. Las mayores federaciones sindicales que representan a los trabajadores petroleros, la Federação Única dos Petroleiros (FUP) y la Federação Nacional dos Petroleiros (FNP), emitieron declaraciones en mayo de 2025 que reclaman la suspensión de las exportaciones de petróleo a Israel debido a sus acciones militares en Gaza. Estas movilizaciones consideran al petróleo como un vínculo material entre los recursos brasileños y la perpetuación de la guerra israelí, con el argumento de que este comercio socava los compromisos de Brasil en materia de derechos humanos y sus principios constitucionales de promoción de la paz y la autodeterminación (FNP y FUP, 2025). Esta campaña reunió al movimiento BDS, sindicatos y otros actores de la sociedad civil. Sin embargo, hasta la fecha (octubre de 2025), parecería que el volumen de exportaciones de crudo y sus derivados destinadas a Israel ha disminuido considerablemente. No obstante, existen sospechas de que aún se darían exportaciones indirectas y trianguladas (operaciones de barco a barco con cambios en países intermediarios antes del destino final), por lo que se mantienen los reclamos por el embargo oficial y que el Estado brasileño adopte una política comercial basada en principios (Opera Mundi, 2025).

La suspensión de la compra de los obuses de Elbit (mencionada antes) es señal de un cambio reciente en la actitud del Gobierno hacia las importaciones de armas israelíes. Otra es el anuncio del canciller en agosto de 2025 de que Brasil estudia la posibilidad de prohibir las exportaciones de material militar a Israel. No obstante, Brasilia no ha dado marcha atrás con respecto a los principales acuerdos militares o de agroindustria con Israel, ni se retiró de grandes tratados como el TLC entre el Mercosur e Israel. Cabe señalar, en este contexto, que de los cuatro acuerdos bilaterales que Bolsonaro firmó con Israel en 2021 (tres de los cuales tenían que ver con cooperación militar, de seguridad y de aviación), uno ya está vigente y tres esperan la aprobación del senado brasileño. El movimiento BDS y sus socios reclamaron que el presidente cancele estos acuerdos, algo que está dentro de sus facultades antes de que el Congreso vote su aprobación (Blumer, 2024).

Dado que el Gobierno no ha tomado suficientes medidas concretas, crece la presión de la sociedad civil tanto en Brasil como en Palestina para la ruptura de relaciones entre Brasil e Israel (BADIL, 2024). La sección a continuación explora cómo la solidaridad brasileña con Palestina se vincula con las luchas nacionales, y cómo creció el movimiento BDS en el país, culminando en la enorme campaña que se desarrolla actualmente, con sus reclamos de acciones más que palabras.

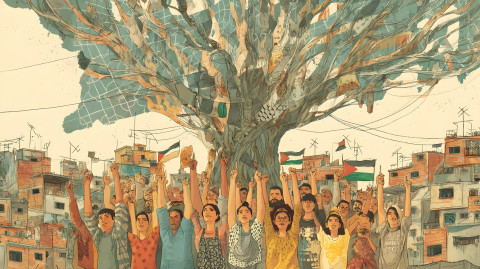

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Resistencia y solidaridad: luchas conjuntas

El reconocimiento de la lucha palestina siempre ha estado presente en los movimientos sociales brasileños, pero la solidaridad concreta surgió debido a la valoración de los paralelos históricos existentes entre el trato que los palestinos reciben de Israel –como un Estado de asentamientos coloniales que impone un sistema de apartheid a la población palestina, no solo de facto sino también de iure– y el trato que reciben las poblaciones negras, indígenas y otros grupos subalternos en la práctica en Brasil. Los movimientos negros brasileños reconocen cómo las tácticas aplicadas contra el pueblo palestino se exportan para ser utilizadas por el aparato militar de Brasil contra la juventud negra y periférica y los pueblos indígenas (Almapreta, 2023). A diferencia de Israel, Brasil no es un Estado de apartheid por ley, pero no obstante carga con un fuerte legado de violencia colonial. Esa violencia consolida la autoridad soberana al eliminar o neutralizar grupos percibidos como amenazas para los regímenes existentes de acumulación, relaciones de propiedad y control político. Por ejemplo, los indígenas yanomamis8 sufrieron cientos de muertes vinculadas a la minería ilegal, mientras que las comunidades negras soportan una violencia estatal sistémica a través de una policía militarizada y la llamada Guerra contra las Drogas, como lo ejemplifican las recientes muertes en la región de Baixada Santista (Almapreta, 2023).

Las exigencias económicas contribuyen a estas dinámicas de opresión, en ambos países. En Brasil, con Bolsonaro, la desregulación facilitó la extracción ilegal en tierras indígenas, especialmente dentro de la reserva yanomami, e integró el oro extraído ilegalmente a los mercados internacionales. En Israel, la crisis económica posterior a 2008 aumentó la presión para confiscar tierras palestinas como reacción a la crisis doméstica del costo de vida. Ambos casos demuestran cómo la expansión de asentamientos de colonos y el genocidio sirven no solo a fines políticos, sino también económicos (Huberman, 2024).

En ambos contextos, aunque con diferentes especificidades, la violencia estatal afecta de forma desmesurada a las poblaciones racialmente subalternas, cuya resistencia es percibida como un desafío fundamental al régimen de acumulación, las relaciones de propiedad y la soberanía política del Estado. Tales dinámicas conllevan el ejercicio del “poder de eliminación”, que se manifiesta a través del asesinato, la expulsión, la asimilación y el confinamiento. Estas estrategias tienen el objetivo de consolidar la soberanía colonial sobre los territorios expropiados y facilitar la acumulación primitiva. Importa señalar que la explotación y la eliminación no son mutuamente excluyentes, sino más bien modalidades intercambiables del poder colonial de asentamientos incrustadas en las relaciones capitalistas (Huberman, 2024).

Muchos actores de la sociedad civil brasileña, y especialmente los movimientos negros y de favelas, consideran que la militarización de territorios en Brasil y Palestina puede interpretarse como regímenes conectados de gobernanza racializada que operan mediante lógicas compartidas de excepción, confinamiento y vigilancia, aun cuando se desarrollan en contextos históricos y legales no equivalentes. En las favelas y periferias brasileñas, las operaciones policial-militares, la vigilancia datificada y el monitoreo ambiental constituyen una infraestructura de control que normaliza la letalidad y suspende derechos. En los territorios palestinos ocupados, los puestos de control, las redadas y las fronteras que emplean tecnología sensorial aplican una arquitectura paralela de restricción. Lo que vincula estos espacios es una circulación transnacional de doctrinas, tecnologías y redes de adquisición (drones; plataformas de inteligencia, vigilancia y reconocimiento; policía predictiva; software de “ciudades inteligentes”) mediante las cuales los proveedores y los aparatos burocráticos de seguridad trasladan técnicas comprobadas en un contexto a la administración de rutina en otro. El resultado es un paradigma de “seguridad-desarrollo” que se refuerza mutuamente, al tratar a las poblaciones racializadas como amenazas gobernables y a los espacios como laboratorios para la experimentación gerencial, mientras oculta las desigualdades estructurales que subyacen tras los relatos de eficiencia, modernización y gestión de riesgos (Martins y Farias, 2024).

Los megaeventos celebrados recientemente en Brasil, especialmente los Juegos Olímpicos de Río de Janeiro en 2016, consolidaron la militarización de la vida cotidiana en el país: los regímenes de seguridad excepcionales, las adquisiciones aceleradas y la infraestructura de vigilancia se normalizaron y luego se reutilizaron para la gobernanza de rutina en favelas y comunidades urbanas. Este montaje de seguridad impulsado por los Juegos Olímpicos (patrullas blindadas, centros de mando y control, redes de cámaras y policía basada en datos) reformuló el orden público como un estado de excepción permanente, lo que legitimó la gestión constante de los territorios racializados como zonas de “riesgo”. Esta aplicación doméstica de medidas extraordinarias refleja circuitos transnacionales de tecnologías y doctrinas de seguridad, al alinear la gobernanza urbana de Brasil con modelos perfeccionados en otros contextos de ocupación y confinamiento, y al reforzar el tratamiento de los espacios vulnerables como laboratorios para la experimentación gerencial. (PACS, 2017)

La intensificación de estas formas estructurales de opresión ha sido facilitada por el ascenso de Gobiernos de ultraderecha tanto en Brasil como en Israel. El brasileño Jair Bolsonaro y el israelí Benjamin Netanyahu son ejemplos de formas de “fascismo periférico” que legitiman y amplifican la violencia estatal, al extenderse más allá del fundamentalismo religioso y los marcos ideológicos conservadores. Este fascismo periférico refuerza el colonialismo interno, las estructuras de apartheid y la profundización de la acumulación originaria bajo las exigencias neoliberales (Huberman, 2024).

En este contexto, el movimiento brasileño de solidaridad con Palestina ha crecido constantemente desde mediados de la década de 2000, basado en los principios del BDS, las alianzas interseccionales y las críticas al militarismo y el greenwashing. El movimiento BDS surgió en 2005 como un llamado unificado de más de 170 organizaciones de la sociedad civil palestina que exigían el fin de la ocupación y la colonización, la igualdad plena para las y los palestinos y el cese del sistema de apartheid de Israel, así como el respeto al derecho de retorno de los refugiados (Movimiento BDS, 2005). En Brasil y América Latina, el BDS ganó impulso a través de las actividades de sindicatos, asociaciones estudiantiles y académicas, y grupos en las favelas y el medio rural que adaptaron la plataforma internacional del BDS a las campañas locales, la presión sobre instituciones públicas, boicots culturales y políticas de compras, situando a Palestina dentro de luchas mayores contra el racismo, la militarización, la agroindustria y el extractivismo. (Misleh, 2016).

En 2006, el Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación Superior (ANDES) aprobó una moción formal de apoyo al pedido internacional de la sociedad civil palestina por el BDS (ANDES-SN, 2025). En febrero de 2006, la Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT), la mayor central sindical de América Latina, emitió una declaración de rechazo al propuesto TLC entre el Mercosur e Israel, tras un llamamiento del BDS que advertía que haría a Brasil cómplice del apartheid israelí (Badil, 2007).

En 2010 se creó por primera vez en Brasil y formalmente un grupo de BDS, centrado en la resistencia a la militarización y la campaña en contra de Elbit Systems. El grupo profundizó las alianzas entre la solidaridad con Palestina y los movimientos basados en favelas y quilombos urbanos.9 Simultáneamente, los eventos de Julio Negro10 en Río de Janeiro y San Pablo conectaron la violencia estatal dentro de las periferias de Brasil –caracterizada por policía racista y la injusticia en materia de vivienda– con la ocupación militarizada de Israel en Palestina. En 2014, el movimiento BDS brasileño logró una gran victoria, al detener una propuesta de expansión de la empresa de Elbit en Porto Alegre (Carta Capital, 2019).

Las primeras actividades del BDS dirigidas al sector de la agricultura y el medio ambiente fueron esfuerzos para resistir los intentos de ingreso de Mekorot al mercado brasileño (mencionado anteriormente). En 2009, la CUT lideró una campaña contra un acuerdo entre Mekorot y la distribuidora de agua pública de San Pablo, que involucró a trabajadores de la empresa estatal y también a pequeños agroproductores de la región (CUT, 2009). Unos años más tarde, en 2014, el Movimiento de Afectados por las Represas (MAB) y el Movimiento de Pequeños Productores (MPA) aunaron esfuerzos para impedir un acuerdo entre Mekorot y el estado de Bahía (Carta Capital, 2019). Más recientemente, la dirigencia del Movimiento de Trabajadores Rurales Sin Tierra (MST) vinculó públicamente las demandas de reforma agraria y antiextractivistas a la solidaridad con Palestina, al considerar que ambas son luchas contra la apropiación capitalista y el militarismo. El estudio de International Viewpoint (2024) sobre el MST enfatiza la forma en que el movimiento posiciona su solidaridad como parte de una resistencia anticolonial mundial más amplia.

Los grupos brasileños de BDS favorecen el trabajo en coalición y a menudo colaboran con partidos de izquierda. Por ejemplo, colaboraron con el PSOL (Partido Socialismo y Libertad), que aprobó una resolución en 2018 donde reafirmaba su apoyo al BDS y reclamaba el embargo a las exportaciones militares de Israel destinadas a Brasil, vinculando expresamente las tecnologías israelíes con la represión doméstica (PSOL, 2018).

En 2019, catorce años después de la creación del movimiento BDS, la cobertura de prensa en Brasil destacó sus impactos acumulativos y “victorias” visibles, que han ayudado a normalizar las tácticas del BDS –desinversión empresarial, cancelaciones culturales y debates políticos sobre comercio y cooperación militar– a la vez que señalaba ciclos de reacción (jurídica, diplomática y reputacional) que buscan limitar la incidencia del movimiento (CartaCapital, 2019). Estas dinámicas subrayan el carácter dual del BDS como un proyecto estructurado, arraigado tanto en el derecho internacional y principios antirracistas, como en un repertorio estratégico que apunta a la complicidad institucional y no a los individuos, con el objetivo de trasladar costos e incentivos en los mercados, las universidades, los circuitos culturales y la contratación pública (Misleh, 2016; CartaCapital, 2019).

Las multitudinarias protestas de Julio Negro en San Pablo y Río de Janeiro ya mencionadas, junto con otras protestas similares, también lograron un avance simbólico pero importante al vincular directamente los sistemas de armas de Israel con la vigilancia policial militarizada de las favelas en Brasil. Al replantear la solidaridad con Palestina como algo inseparable de las luchas por la justicia racial, la desmilitarización y la protección ambiental local, estos movimientos amplían su base y ligan la solidaridad internacional a las demandas locales (Martins, 2021).

A pesar de estos avances del movimiento BDS, ya persistían los reveses antes del inicio del genocidio israelí en Gaza en 2023: el TLC entre Mercosur e Israel siguió en vigor, lo que aseguraba a Israel un estatus comercial preferencial, mientras que las exportaciones agroindustriales y petroleras brasileñas continuaban socavando la difusión del boicot. Además, la inercia gubernamental y las presiones políticas hicieron que se estancaran otras medidas legislativas o ejecutivas más abarcativas sobre el asunto, lo que refleja los límites que tienen las victorias de base cuando se enfrentan a intereses económicos y diplomáticos arraigados.

Entonces se desató el genocidio israelí en Gaza. Entre 2023 y 2025, mientras el genocidio se transmitía en directo y a diario por Internet, crecía la visibilidad del movimiento BDS en Brasil. En este contexto, el BDS logró victorias concretas gracias a una serie de movilizaciones y campañas. Como ya se mencionó, en 2024 se suspendió el mayor contrato militar propuesto en los últimos años con Elbit Systems: la compra planificada de obuses por 150-200 millones de dólares. Ese año también se canceló una feria de innovación conjunta en la Universidad Federal de Ceará (UFC), que tenía previsto exhibir la asociación con instituciones israelíes en ámbitos como la gestión del agua y la seguridad alimentaria (Gazeta do Povo, 2024). Y en 2025, la Universidad Estatal de Campinas (UNICAMP), la Universidad Federal Fluminense (UFF), la Universidad Federal de Ceará (UFC) y la Universidad Federal de Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) cancelaron todos sus acuerdos con universidades israelíes (Folha de São Paulo, 2025b).

Estos logros se dieron en el contexto de un cambio en la opinión pública, según lo confirmaron numerosas encuestas. En junio de 2025, más de 15 000 personas, entre ellas nombres destacados de las artes, la música y la política –como Chico Buarque, Ney Matogrosso y Francisco Rezek– firmaron una petición que exigía sanciones concretas contra Israel, como el embargo militar total y el fin del TLC (Folha de São Paulo, 2025a). En agosto, el ministro de Relaciones Exteriores, Mauro Vieira, anunció por primera vez que Brasil consideraba tomar medidas económicas específicas contra Israel, como la reevaluación del TLC y de las exportaciones de armas.

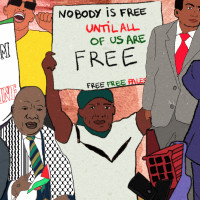

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

La contraofensiva y los grandes desafíos

A pesar de los logros resumidos anteriormente, la resistencia política y las barreras estructurales continúan limitando el avance del BDS en Brasil y la solidaridad con Palestina en general. Entre estas barreras se encuentran las redes de presión sionistas, la inercia gubernamental, la represión legal y la interpretación ideológica de Israel como un socio benigno en la innovación.

Dos importantes grupos de presión sionistas que están activos en Brasil son la Fundación Aliados de Israel (IAF, por sus siglas en inglés) y la Confederação Israelita do Brasil (CONIB). La IAF mantiene un grupo centrado en Brasil integrado por legisladores alineados con bloques evangélicos y conservadores que se dedican a contrarrestar la movilización pro-Palestina en el país. Estos legisladores se oponen a las mociones del BDS y promueven las relaciones con Israel en los foros legislativos (Israeli National News, 2023). Por su parte, la CONIB opera como una mediadora central entre las instituciones comunitarias y los actores estatales, en la defensa del poder blando israelí y el cuestionamiento del discurso crítico, particularmente en los medios de comunicación y el ámbito académico.

Además de participar en amenazas legales y lawfare o guerra jurídica, las redes pro-Israel, como la IAF y la CONIB, buscan definir las críticas a Israel como discurso de odio, al afirmar que las críticas a la política israelí suelen ocultar una intención antisemita, en una estrategia que se utiliza para deslegitimar a los activistas. Para la ley brasileña, el antisemitismo es una forma de racismo y es un delito penal; sin embargo, no existe una definición oficial del término. Los grupos sionistas presionan para que “antisemitismo” se aplique de forma amplia con el fin de suprimir el activismo de solidaridad con Palestina. Y un legislador de derecha presentó recientemente un proyecto de ley que impondría la definición de antisemitismo de la Alianza Internacional para el Recuerdo del Holocausto (IHRA), que es conocida por ser utilizada como un instrumento de censura de las críticas al régimen israelí. Sin embargo, judíos antisionistas, como los integrantes de Voces Judías por la Liberación (VJL), combatieron la iniciativa y el Gobierno federal terminó por retirarse de la IHRA, de la cual era miembro observador desde 2021, de forma indefinida (Folha de S. Paulo, 2025b).

Si bien –desde que comenzó el genocidio– el presidente Lula ha utilizado un lenguaje diplomático fuerte, que incluyó el retiro del embajador de Brasil ante Israel y la degradación del estatus diplomático de Israel, y aunque el Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores anunció que está considerando medidas contrarias a ese país, los cambios en la política vigente siguen siendo limitados. El TLC entre Mercosur-Israel sigue operativo y los organismos gubernamentales no han suspendido los principales compromisos militares o comerciales. Mientras tanto, los estados y municipios continúan con la compra de equipos israelíes. Y a pesar de la gran victoria que fue la paralización de la entrega directa de petróleo a Israel en 2025, no se adoptó un embargo formal y continúan los envíos indirectos.

Un motivo que explica este progreso limitado es el hecho de que los legisladores alineados con el sionismo (algunos de ellos aliados del Gobierno) y las élites empresariales siguen presionando a los ministerios brasileños para que se preserven los lazos comerciales entre Brasil e Israel en las áreas de seguridad, agricultura y energía. Un ejemplo es la votación unánime del Senado brasileño en junio de 2025 a favor de establecer el 12 de abril como el Día de la Amistad con Israel, en celebración de los lazos históricos y económicos entre los dos países –durante el genocidio en Gaza (Câmara dos Deputados, 2025). Este fue un mensaje claro a la presidencia, incluso por parte de senadores del propio partido del presidente, tras las fuertes declaraciones de Lula contra las acciones de Israel. Mientras tanto, el Ministerio de Defensa, que mantiene una coordinación con socios vinculados a Elbit y comercia con mercados israelíes, defendió públicamente su asociación con empresas israelíes y calificó los intentos de detenerlas como "interferencia ideológica" (O Globo, 2024).

Un factor que puede explicar la orientación positiva de las élites brasileñas hacia Israel es la estrategia internacional de promoción de la marca de Israel (mencionada anteriormente), que pone énfasis en la tecnología climática, la innovación agrícola y la cooperación en seguridad. Como parte de esta estrategia, Israel participa en muchas ferias y eventos de innovación en Brasil. En conjunto, esta estrategia permite a Israel exhibirse como socio en el desarrollo brasileño, blanqueando en los hechos sus políticas de ocupación. Estas narrativas repercuten en las élites brasileñas y eclipsan las exigencias de rendición de cuentas.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Hacia adelante: Estrategias para asegurar que Brasil lidere en la defensa de los derechos palestinos

Brasil ocupa una posición fundamental en el panorama de la política exterior de América Latina. Es la mayor economía de América del Sur y una de las 10 principales economías del mundo en 2025. También desempeña un papel importante en los BRICS y en el movimiento por un orden internacional multipolar. El liderazgo histórico de Brasil en el Sur Global y sus profundas conexiones económicas con Israel le otorgan una influencia singular para inclinar la balanza hacia la rendición de cuentas. Sin embargo, esto requiere una ruptura deliberada con la complicidad estructural, lo que incluye el comercio militar, la agroindustria y las exportaciones de petróleo.

En este contexto, el éxito del movimiento brasileño de solidaridad con Palestina depende de la capacidad de entablar alianzas amplias e interseccionales que unan las luchas urbanas, rurales, ambientales, laborales y antirracistas. Movimientos como el MST, MAB, MPA, el Movimiento Negro Unificado (MNU) y colectivos de favelas demostraron el potencial que tiene vincular la reforma agraria, la justicia en materia de vivienda y la defensa ambiental con la liberación palestina (Tricontinental, 2024). Los sindicatos, las organizaciones feministas, los movimientos negros, las campañas por la justicia climática y las asociaciones estudiantiles también son aliados importantes. Las campañas coordinadas con la participación de estos diferentes actores pueden amplificar el mensaje de que el sistema de apartheid de Israel no es un fenómeno aislado y geográficamente distante, sino que está ligado a las mismas lógicas extractivistas y militarizadas que perjudican a las comunidades marginadas de Brasil.

En particular, es necesario impulsar campañas dedicadas a los acuerdos de defensa y de comercio con Israel. La paralización del acuerdo de artillería ATMOS con Elbit Systems en 2024 demostró el poder de la presión pública y la movilización sindical, y puede servir como precedente para la cancelación de todos los acuerdos de armas con Israel.

El mismo enfoque puede aplicarse en relación con el TLC entre Mercosur e Israel. Brasil debería tomar la iniciativa y cancelar unilateralmente el acuerdo, aun si los socios del Mercosur no lo hacen de inmediato. En paralelo, sindicatos como la FUP y la FNP, en el sector petrolero, y la CUT, deberían continuar ejerciendo su poder económico y negarse a facilitar las exportaciones de petróleo a Israel, así como la cooperación técnica con empresas vinculadas a ese país.

Además, los actores de base deben presionar al Gobierno federal para que pase de la condena retórica a la acción sustancial. En términos prácticos, el movimiento BDS reclamó sistemáticamente la imposición de sanciones y medidas de rendición de cuentas que sean efectivas, legales, proporcionales y diseñadas para apuntar a las estructuras de opresión. Es importante señalar que la adopción de estas medidas es una obligación legal, no una cuestión de discrecionalidad, como afirma hoy prácticamente un consenso de expertos en derecho internacional. En el plano nacional, Brasil debe cumplir con sus obligaciones de derecho internacional, particularmente aquellas derivadas de la Convención sobre el Genocidio, la Convención sobre el Apartheid y las sentencias de la Corte Internacional de Justicia de febrero y julio de 2024, entre otras. En este sentido, son necesarias las siguientes medidas de rendición de cuentas:

- Cesar todas las exportaciones de energía al Israel del apartheid.

- Anunciar, legislar e implementar un embargo militar total y completo contra Israel, que incluya la exportación e importación de material militar y de doble uso, y el cese inmediato de todos los acuerdos de cooperación militar y de seguridad con Israel.

- Cancelar el TLC actualmente en vigor con Israel.

- Suspender el acuerdo de viaje sin visa para las y los ciudadanos israelíes y adoptar medidas de verificación para asegurar que las personas que ingresen al país no hayan participado de crímenes de atrocidad.

- Fortalecer el compromiso de Brasil con el procesamiento de personas –más allá de su nacionalidad (que incluye a aquellas con doble nacionalidad brasileña-israelí)– sospechosas de haber participado en (incluyendo la incitación a) crímenes de guerra, genocidio, crímenes de lesa humanidad y apartheid.

- Unirse al Grupo de La Haya y firmar la declaración del Grupo, para demostrar el compromiso de Brasil con la acción colectiva en defensa del derecho internacional y la protección de los derechos fundamentales.

La implementación de estas medidas representaría no solo el cumplimiento de las obligaciones de Brasil con el derecho internacional, sino también el cumplimiento de su responsabilidad moral de contribuir con los esfuerzos internacionales en defensa de la justicia, los derechos humanos y el Estado de derecho. En particular, la participación del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Brasil (Itamaraty) –que tiene una historia de diplomacia proactiva– en procedimientos legales internacionales relacionados con los crímenes israelíes sentaría un precedente regional que alentaría a otros Gobiernos latinoamericanos a tomar medidas similares. Cabe señalar aquí que Brasil se sumó recientemente al caso de Sudáfrica en la Corte Internacional de Justicia contra Israel, amparado en la Convención para la Prevención del Genocidio. Esto representa una victoria para el movimiento pro-Palestina en Brasil, y también aumenta la presión sobre Brasil para actuar y prevenir el genocidio de Israel.

Las estrategias de Israel de greenwashing y de promoción de marca en tecnología de seguridad requieren una impugnación sistemática mediante campañas de educación crítica. En el contexto brasileño, estas iniciativas deberían priorizar la producción de materiales en portugués que examinen críticamente las operaciones de las empresas israelíes, como Netafim y Adama, que lucran con lo que se ha caracterizado de apartheid del agua, mientras se destaca también cómo los relatos de tecnología agrícola funcionan para ocultar y legitimar los procesos de despojo de tierras por parte de los asentamientos de colonos. Además, establecer conexiones expresas entre las tecnologías militares israelíes y las propias prácticas de Brasil en materia de vigilancia y control policial doméstico de activistas y defensores ambientales tiene el potencial de generar una resonancia social más amplia. Al situar estas dinámicas tanto en las luchas urbanas como rurales, estas campañas pueden mejorar la conciencia pública, fortalecer las solidaridades y situar la liberación de Palestina en las luchas actuales de Brasil por la justicia racial, social y ambiental.

Las acciones de universidades, como la Semana del Apartheid Israelí, siguen siendo cruciales, pero también es importante aumentar la proyección hacia los espacios de movimientos sociales. En ese sentido, las campañas visuales en las redes sociales y en los principales centros urbanos deberían enfatizar los relatos interseccionales de resistencia.

Como ya se mencionó, durante la COP30 en Belém, los movimientos de base celebrarán la Cumbre de los Pueblos, que reunirá las voces de movimientos sociales de todo el mundo, entre ellos movimientos y organizaciones palestinas, como el Comité Nacional de BDS (BNC), Stop the Wall, PENGON –Amigos de la Tierra Palestina, Global Energy Embargo for Palestine (GEEP) y Palestinian Institute of Public Diplomacy (PIPD). Durante la Cumbre, estos grupos pondrán a Palestina en la palestra, no solo como un tema abstracto sino también de forma concreta, en cuanto a fortalecer las redes con sindicatos y movimientos por los derechos humanos y ambientales, y generar una solidaridad concreta que aborde las luchas interseccionales. Juntos, dejarán en claro que la liberación palestina es un sine qua non de la justicia climática real.

Conclusión

Brasil tiene ante sí una oportunidad histórica para apoyar a Palestina. Como anfitrión de la COP30 y de la Cumbre de los Pueblos, toda la atención recaerá sobre el Gobierno y la sociedad civil del país, y si tomarán acciones concretas para detener la complicidad con el régimen de apartheid y genocida israelí.

El progreso ya es visible. Los movimientos sociales, desde el MST hasta las asociaciones estudiantiles, han logrado victorias clave: detener los contratos con Mekorot y Elbit, presionar a las universidades para que cancelen ferias israelíes y forzar debates públicos sobre las exportaciones de petróleo y el embargo energético total. Además, la solidaridad sindical ha vinculado la liberación palestina con los derechos laborales y la justicia ambiental, lo que demuestra cuán profundamente se entrelazan estas luchas. Esta interseccionalidad debe ser explorada y ampliada aún más.

Sin embargo, el Estado brasileño aún se mantiene vacilante. A pesar de la poderosa condena de Lula al genocidio israelí en Gaza y del retiro del embajador de Brasil ante Israel, las redes estructurales de cooperación militar, las exportaciones de petróleo y el comercio de la agroindustria permanecen en gran medida intactas. Los grupos de presión sionistas y las élites económicas son obstáculos para una acción de peso. Si las bases no mantienen una presión sostenida, Brasil corre el riesgo de permanecer cómplice. A la vez, las campañas de solidaridad con Palestina no siempre han conseguido el apoyo amplio de la sociedad civil, y algunos movimientos aún ven la solidaridad con Palestina como un tema abstracto y discursivo.

El camino a seguir requiere una mayor organización interseccional; el trabajo constante con los sindicatos, movimientos estudiantiles y grupos ambientalistas y de defensa del territorio; la presión constante sobre el Gobierno; una mayor coordinación regional; y una estrategia de educación pública que desmantele la propaganda israelí.

Brasil tiene tanto la obligación moral como el poder político para ir más allá de la solidaridad retórica. Al acabar de lleno con la complicidad –militar, diplomática y económica– puede ayudar a impulsar un realineamiento regional y avanzar en la campaña mundial para desmantelar el apartheid israelí. Si aprovecha esta oportunidad, Brasil puede convertirse en la voz que lidere en la confrontación del apartheid y el militarismo israelíes, dentro del Sur Global y en foros internacionales, como el BRICS, el Mercosur, la Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA) e incluso la ONU. Los próximos años determinarán si Brasil elige seguir siendo un facilitador del militarismo o si asume plenamente su papel histórico como defensor de los derechos humanos y el derecho internacional. El futuro de la lucha palestina, y la lucha mayor contra los sistemas de opresión mundial, se definirá en parte por esta elección.

Las opiniones expresadas en este artículo son exclusivamente las de los autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista o las posturas de TNI.

Serie Liberación de Palestina

Ver series

-

El contexto de Palestina Israel, los Estados del Golfo y el poder de los Estados Unidos en Oriente Medio

Fecha de publicación:

-

Actitudes y solidaridad de África con Palestina De la década de 1940 al genocidio de Israel en Gaza

Fecha de publicación:

-

Al fallarle a la revolución sudanesa, le fallamos a Palestina Lecciones de los vínculos entre Sudán y Palestina en materia de política, medios de comunicación y organización

Fecha de publicación:

-

Fantasías de sostenibilidad/realidades genocidas Palestina contra un mundo de apartheid ecológico

Fecha de publicación:

-

Vietnam, Argelia y Palestina Pasar la antorcha de la lucha anticolonial

Fecha de publicación:

-

Del antiimperialismo internacional a los guerreros diente de león La solidaridad de China con Palestina de 1950 a 2024

Fecha de publicación:

-

El circo de la complicidad académica Un espectáculo tragicómico de evasión en el escenario mundial del genocidio

Fecha de publicación:

-

India, Israel y Palestina Las nuevas ecuaciones exigen nuevas solidaridades

Fecha de publicación: -

Ecocidio, imperialismo y la liberación de Palestina

Fecha de publicación: