A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Topics

In this fascinating conversation, Adam Tooze and Walden Bello reflect on the fracturing of US power, the rise of China, the growth of nationalisms and the perils and possibilities of a multipolar order.

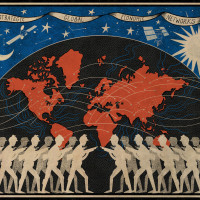

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

Nick: And how do you see it, Walden? Do you think we are in a polycentric order? Where does Trump fit in?

Walden: First of all, let me say I feel very privileged having this dialogue with Adam, who’s one of the world’s leading economic historians. I definitely agree with Adam that we have been on the way to a multipolar word for quite some time. As we speak, the media has made much of Trump’s wanting to make Canada the 51st state and taking over Greenland and the Panama Canal.

However, I don’t think the Trump project is best conceived as a reassertion of US power globally. If there’s a project that might be regarded as a reassertion of US global power, that was Biden’s. The Biden and Harris project was basically the reinvigoration of liberal internationalism, which sought to make the world safe for US capital through the projection of US military and political power and free trade.

That project, which was the post-Pearl Harbor US paradigm, had been damaged during Trump’s first term in office. Only in retrospect can one appreciate how radically the isolationist, anti-globalist and protectionist foreign policy of the first Trump administration broke with liberal internationalism.

Trump, among other things, tore up the neoliberal Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that both Democrats and Republicans championed, considered NATO commitments a burden and threatened to leave the alliance, demanded that Japan and Korea pay more for keeping US troops in their countries or face withdrawal of the US military umbrella, trampled on the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), ignored the IMF [International Monetary Fund] and the World Bank, negotiated the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and stepped across the DMZ [the demilitarised zone in North Korea] .

Looking at this record, one can understand the deep hostility towards Trump, not only of the Democratic Party establishment, but of all political elites – those that believe in the essential role of bilateralism and alliances in promoting US hegemony as well as the neoconservative establishment represented by Dick Cheney that prefers more unilateral methods to advance the same hegemonic project.

And what do I think is a Trump project? Well, Trump is unpredictability personified. But his instincts are basically isolationist and inward-looking, and a significant part of his base is also isolationist. This project might be labelled defensive imperialism as opposed to the expansive imperialism of the liberal internationalist project. It is rebuilding what he and his MAGA outfit consider a damaged core of the empire by putting up a wall against imports, against non-white migrants, and bringing back prodigal US capital back through reshoring via raising tariffs. The focus is on fortifying the US core of the empire, though I would add that he considers Latin America falling within the US sphere of influence. His comments on Canada, Greenland, the Panama Canal, and the Gulf of Mexico reflect this refocusing of priorities on the Americas.

The US posture in most other areas is from this perspective negotiable. Trump certainly does not believe in the new liberal international principle that compromising with or appeasing authoritarianism in one part of the world, like over the war on Ukraine, would be harmful to US interests in other parts of the world.

Nick: What do you see as the underlying causes of this moment – not just the rise of the multipolarity but also the phenomenon of Trump?

Adam: Walden’s description of the shock of the first Trump administration is very comprehensive and compelling, but I see that fraying beginning earlier.

You could go back to the unilateralism of the Bush administration in 2003, certainly on the transatlantic axis that caused considerable ruptures and dynamised the multipolar momentum, both in Beijing and in Moscow.

Beijing’s increasing determination to chart its own course starts in 2008/9 with the realisation that the US is a wobbly and unreliable anchor and with an increasingly assertive position by the Chinese leadership.

2008 is also the moment at which it becomes apparent to the US leadership that the story of globalisation, which is so key to the self-confident projection of US power from the 1990s onwards, could potentially turn against them in different ways.

And we saw it in two crucial respects. One is Russia, because after all, Putin’s Munich Security Conference speech comes just before 2008 [that challenged the unipolar world order] and was followed by the Russian military intervention in Georgia. And then there is Beijing’s offer of climate cooperation as a new model of great power relations, which it looks as though Washington might take up, but then it disperses. Its only fruit is the Paris Agreement of [keeping global temperature rise since industrialisation to] 1.5°C. And then instead what we get is Trump. So, that would be my preface to Walden’s account of the first Trump administration.

We have as key elements of the current global institutional landscape: the return of the activist state, the re-regulation of the market, the return of dynastic capital, and the emergence of Napoleonic capitalists.

Nick: Walden, would you like to add anything and on the underlying causes of this fracturing of global power?

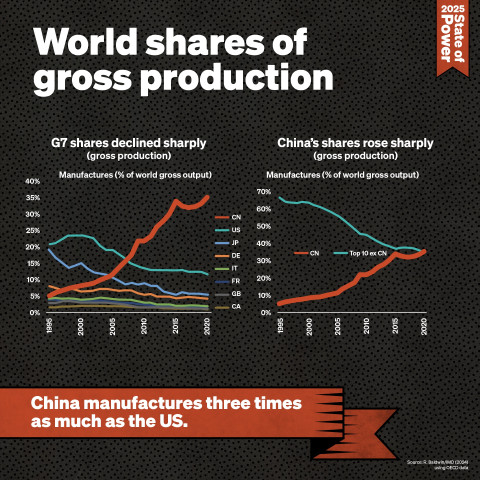

Walden: I agree with Adam. On the point of underlying causes, I would identify three major contributors: first the flight of US transnational capital to China in search of dirt-cheap labour that was less than 5% of the cost of US labour. This was a process that enjoyed the blessings of Washington from the Bush Senior to the Obama administration. Some estimate that the so-called ‘China shock’ cost the US some 2.4 million manufacturing jobs and destroyed that synergy between technological innovation and a dynamic manufacturing sector.

The second major contributor was financialisation, which made the financial sector the favourite for investment, owing to the massive profits that could be made from speculation. Both de-industrialisation and financialisation were key factors in the stagnation of the income and living standards of at least half of the US population and the sharp rise in inequality.

The third major factor we should not underestimate was the overextension of US military power in the Middle East under the Bush Junior administration, which became a trap from which Washington found it very difficult to extricate itself and led to its loss of credibility even with allies.

Now, the obverse of US de-industrialisation was the super-industrialisation of China, which made the fastest run in history from being a complete outsider to the global capitalist system to being at its very centre. And this was in a period of just about 30 years. This involved not just rapid industrialisation, but swift technology acquisition, so that the country’s scientific and technological base is now largely self-sustaining.

Nick: How do you think the US–China relationship and geopolitical rivalry is shaping capitalism?

Adam: I want to double down on something that Walden said about the extraordinary development that we’ve seen from the insertion of China into Western value and supply chains. It involved huge urbanisation of hundreds of millions of Chinese rural dwellers, but it has led in the last 10 years to a situation in which China entirely dominates global manufacturing in practically every key area or is at least a significant rival or major player alongside Western or other East Asian competitors.

As was the case of the US at its manufacturing heights, China’s capacity is now dominated by Chinese domestic demand based on its huge market of 4 billion increasingly affluent people. And so those markets are not just dynamic, but trend-setting. We see this most dramatically in electric vehicles, where the Chinese ecosystem, the market, the demand, the pace-setting, consumer style, technology and manufacturing capacity are all located in China. Major East Asian and European competitors like Toyota and VW face a strategic choice as to whether they hang on in the Chinese market or increasingly rely on various types of protectionism to shield their local markets against Chinese competition.

And it’s worth focusing on car manufacturing, because if you look at the sophisticated large-scale globalisation of supply chains, the auto industry was once the hub of global capitalism. The age of Fordism drifted out of sight in the 1970s and 1980s, but it’s unambiguously one of the key drivers of at least regional development of supply chains.

And we’re seeing here a historic shift of a type we’ve not seen before with the move in the locus of innovation to China, and it’s an internal Chinese development.

So, does this change capitalism? I don’t think so, not per se, because capitalism is a constantly evolving system. It doesn’t have a single unity. It’s not centred on a single technology, but it is a major shift in one of the key areas of the global division of labour.

If I may just expand on one other area, finance. What we’ve seen since 2008 is an increasing bipolarity. We have a US-dominated system centred around the dollar. Once upon a time it was polycentric with the Europeans and East Asian players being significant alongside Wall Street, but that’s largely evaporated since 2008. So, we have a dollar system massively dominated by the key US players – the BlackRocks, the JP Morgans.

And then, separate from that, within Chinese exchange-rate and currency controls, a Chinese system, which again, given the scale of the Chinese market has scale and compares with and is even larger than the JP Morgans, yet it’s not part of the same system.

Now, again, does this change capitalism? I don’t think in principle it does. It changes its geographic scope. It changes its horizon of expectation with regard to globalisation.

The nationalisation tendency , the tendency towards protectionism, is a new and important development, in its aggressive form. Again, it's a bipartisan project in the United States as both the Democrats and the Republicans are on board.

So I think there is this break in America's political economy. But does that fundamentally change capitalism? No, because clearly America's capitalism developed in the 19th century under a massively protectionist system. There were many different ways in which this can manifest and develop.

It changes the direction, it changes the bargaining power of different actors, it changes the points at which bargaining power can be applied and leverage can be applied. And in the form of the Chinese system we are seeing something which doesn't neatly fit a cookie cutter definition of what capitalism is because of the role of the party and state institutions.

In any case, we're seeing a diverse, complex polycentric model in which big shifts are happening, while in others, there's a consolidation of American power within the dollar system.

Walden: I find much to agree with Adam but let me add a few more things here. In terms of the departure from neoliberal ideology, it has been uneven. China, has of course in the last few years touted its model of capitalism as the reason for the success of the country’s development. When Trump tore up the TPP and rejected free trade, he basically accelerated the process of abandoning the neoliberal models of market-driven corporate expansion. Similarly, the Biden administration took a giant step towards industrial policy with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the Chips and Science Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

However, neoliberalism continues to be the ideology of the IMF and the World Bank. In many countries that have their programmes, like my own country, the Philippines, they continue to implement neoliberal policies because the Bretton Woods Institutions have pushed them to legislate these policies and even institutionalise them in their constitutions.

Nevertheless, the massive failure of neoliberal policies will inevitably create tremendous pressures to abandon these policies and force adoption of initiatives that will prioritise social welfare, re-regulation, and a leading role of the state. We saw this with the revolt against neoliberalism in 2019 in Chile, which was probably the most neoliberalised country in the Global South. This is a trend that we will see more and more. In the post-neoliberal state, I believe that national economic goal-setting will be the trend, planning will again become legitimate, and that technocratic decision-making on such fundamental issues as consumption and investment will be more salient.

The greater role of the state in countries where authoritarian or fascist regimes come to power means that a whole host of economic privileges and incentives will be provided to the majority population, while stripping minorities of access to them. India here is a pace-setter.

In terms of relationships among governments, the era of globalisation, which saw the free flow of capital and goods across national borders, guaranteed by multilateral system, will give way to more bilateral relationships in trade, capital flows, aid, and migration. The character of these relationships will be determined by whether countries are geopolitical rivals or whether they are seen as racially or culturally compatible. What Trump calls ‘shithole countries’, meaning most of us in the Global South, will be marginalised from this web of bilateral relationships.

Now, one must also factor in that the institutional landscape of capitalism is changing. The Fordist corporation under managerial control is now only one of several incarnations of capital, as Melinda Cooper has shown. There has been a revival of dynastic capitalism or family-owned wealth transmitted intergenerationally through changes in inheritance laws and favourable tax treatment, with Trump being an example of this phenomenon along with the Koch brothers.

And we have also witnessed the emergence of billionaires with a Napoleonic complex, eager to use their access to the state as well as the media and civil society for their personal goals – like Trump, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos.

So, I would just like to sum up that we have as key elements of the current global institutional landscape: the return of the activist state, the re-regulation of the market, the return of dynastic capital, and the emergence of Napoleonic capitalists.

Adam: On the question of neoliberalism, I find it useful to distinguish between different dimensions of the phenomenon. One is the ideological one, the doctrine, which we can all agree has become very threadbare and fundamentally disrupted and abandoned in some cases quite flagrantly, say by Jake Sullivan announcing the end of the neoliberal era and announcing a new Washington Consensus.

But then you can also think about neoliberalism as a mode of governance, a mode of government. What was really telling, for instance, about the Biden Inflation Reduction Act is the way it worked, which is essentially a public–private partnership. This wasn’t the Green New Deal, nor was it the old New Deal model. It was essentially a bunch of tax breaks for private players. And so much as this was a government scheme to promote green energy, the way it worked was exactly in the manner that the World Bank or the IMF has been prescribing since the late 1980s.

If you look at the most substantial interventions that have been undertaken, they run through central banks acting on repo [repurchase agreement] markets and the balance sheets of financial actors. So, this is a more activist state fuelled by an ideology that is breaking with certain sorts of nostrums of the 1990s, and yet is using the tools quite familiar from that earlier era.

If you look at neoliberalism in a third way, it’s a class project. It’s a question of redistribution. It’s trying to break the existing entrenched defensive structures of the working class, the institutions of the welfare state – and to tear out projects of national development. At that level, you’d have a hard time arguing that there’s been any fundamental change at all. In fact, you could think of the current moment as an amplification of the existing interest structure.

Certainly, this is the reason why the US Inflation Reduction Act is not some sort of assertion of working-class power, but just a reworking of the monopoly interest groups or oligopolistic interest groups within the energy sector. And it turns out you can find green-energy interests that would also like a subsidy from the US state to make their shareholders rich and pursue projects which are environmentally transformative in various ways but are still as very much about profit as anything before. So, this will be the next era: Duke Energy and players like this in the US system. Nothing changes there.

However, if we think of neoliberalism as a cultural project, as an idea of the subjectification of human beings, not as citizens or as members of social networks, but as market actors, then the platform economies of the current moment are the most radical embodiment of precisely that model. You can see it in the self-branding, the self-fashioning, the self-promotion of literally tens of millions that aspire to be influencers, both in the US and Chinese social media system.

There certainly are ways in which US platform economies are special. But you don’t have to spend very long in China to realise that its society is much more profoundly organised around platform structures than anywhere in the West. You simply can’t live there without being on the WeChat system. You can’t buy anything!

So, it’s a much more deeply integrated system at the level of individual subjectification, which drives the process of marketisation and self-marketisation increasingly aggressively. It is also truly global in scope that reaches the Philippines and Indonesia as much as China and large parts of Africa.

There are elements of neoliberalism which are fraying, such as its relationship to US power. It wasn’t called the Washington Consensus for nothing. It was centred on a certain conception of US power, which is fraying and fragile. However, most of the elements in between, which have to do with this much more pervasive paradigm – of governance, of class power, of subjectification –these are still alive and well, in some ways moving at a speed, pace, pervasiveness and global scale which fulfils the true fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s prophets of market liberalisation.

There were elements of [the neoliberal ideologues’ message] which had to do with capital-account liberalisation and the details of privatisation, but in a broader sense, do we now live globally in societies which are closer to the Milton Friedman ideal of market-driven interaction? Of course we do. And on the scale of billions of people.

Nick: For a long period, there was a shift towards understanding transnational corporations as the key actors on the global stage. Is that shifting right now with the geopolitical rivalry and the return of the nation-state?

Adam: We’re in a testing phase. We’ve certainly left behind the era in which one could straightforwardly and simply argue that the ultimate powers were the big global corporate players.

We’ve left behind the era in which it was just taken for granted that the US Treasury Secretary would be a former CEO of Goldman Sachs. The scenario in which you have a Hank Paulson, a former CEO of Goldman Sachs appointed by the Bush administration in the early 2000s to run the strategic dialogue with China over economic relations is unthinkable now. There has been a deep shift.

My own understanding of political economy, both in the domestic and the international realm, is of a contestation with variable geometry. There are clearly massive corporate powers that at all sorts of levels exercise influence and structure, both the details of regulation and the conditions of possibility of government action and the realm of what is and is not discursively thinkable.

But they stand opposite – sometimes in very close cooperation with and sometimes in antagonism with – other key players and state power and the security apparatus. And it’s going to be very interesting to see how this plays out.

We have a test case in front of us. There are two key bellwethers of the US relationship with China. One is Apple and the other is Tesla and Musk. And it will be very interesting to see how the interests of particular corporations are being either challenged or actually carefully sheltered and protected.

For instance, we know that despite the announcements of heavy tariffs by the first Trump administration on all trade with China, Apple ended up, after some highly successful lobbying, with very significant carve-outs for all the key elements of its supply chain. As America’s most valuable public company, the first to break the three-trillion dollar [market value] threshold, this isn’t something a White House easily does, to attack the interests of an Apple, even if at some level its business and supply chain model goes deeply against US national security strategy at that moment.

And it’ll be very interesting to see how Elon Musk’s Tesla thing plays out. We don’t know how these interests are going to be articulated.

And there are reverberating effects where Huawei, for instance, was singled out for an absolutely extraordinary campaign directed against a particular company by the US state apparatus. The consequence of that in part is that Huawei’s position within the Chinese space shifts. So, while it loses global markets and is subject to this really surgical strike (rather like drone warfare), its freedom of manoeuvre and its scope for action increase both within the vast Chinese economy and the various elements of the One Belt, One Road programme.

So, it’s a very complex geometry. And I don’t think we know yet how this is going to play out. I know it sounds a little open-ended, but that’s the only realistic account of the current moment.

There are elements of neoliberalism which are fraying, such as its relationship to US power. It wasn’t called the Washington Consensus for nothing....However, most of the elements in between.. of governance, of class power, of subjectification –these are still alive and well and moving at a speed, pace, pervasiveness and global scale which fulfils the true fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s prophets of market liberalisation.

Nick: And how do you see the changing relationship of corporations and state, Walden?

Walden: I would like to add to this idea of a period of contestation the case of TikTok, which Trump has asked the Supreme Court to hold off on banning to let him decide.

And so there’s this sort of playing around, groping to feel out the relationship between the state and foreign transnational corporations.

From my perspective in the Global South, my sense is the nation-state is likely to become an even a more powerful actor relative to the market and the private sector. This is due to the realisation that economic prosperity will depend on governments actively supporting technological advance and preventing rival countries from getting advanced technology.

Transnational corporations I fully agree will continue to be influential actors, but they will increasingly find themselves having to adapt to government policies like reshoring and transferring key parts of their value chain from rival countries.

They’ve also become much more defensive to attacks from populist elites. One must remember that transnational corporations were accused by [Trump Trade Advisor] Peter Navarro and others in MAGA as having betrayed the US by moving to China. So, this backlash is important in terms of assessing their relationship to the state at this point.

Adam: At some level corporate power is aligned with the professional managerial class. Ultimately who owns it and who generates the profits is one thing, but most very large corporations are held in quite diverse ways and then run at one step removed by funds like BlackRock, which themselves embody a kind of algo-based professional managerial approach to the governance of global capitalism.

At some level, those social groups are deeply enmeshed with a structural and cultural liberalism that is toxic to the MAGA crowd. This doesn’t mean that the MAGA crowd doesn’t like business. It just doesn’t like that version of business, which is corporate, large-scale, and dominated, as one commentator said by ‘lawyers and shrinks’. They are instead attracted to a petit bourgeois model, what some analysts in the US called the American gentry. It’s the car dealership, the large construction company, the small-scale retail chain, the person who has a bunch of Chick-fil-A franchises who are easily in the top 1% of the US income and wealth distribution. In other words, they are probably worth $40 million, have a big mansion, a second home in Florida, and a motor yacht, but they do not belong among the corporate titans at Davos.

So, within the Trump camp, somebody from Wall Street has ended up in the

Treasury position, but he’s not a former CEO of a gigantic bank. The kind of paradigmatic big-money person around Trump are made up of private equity, hedge-fund people. Their advantage is they’re wealthier than those running a big bank. Jamie Dimon [CEO of JP Morgan Chase] struggles to earn a billion dollars over the course of his career. If you’re working in private equity or hedge funds, that’s an annual salary in a good year for the best-paid people.

But it’s above all, it’s freebooting. It’s easy come, easy go. You’re working in a small shop with 200 to 200 to 300 employees, so you can set your own culture, you can set your own style.

I think in understanding the way in which the relationship between populist politics and capitalism has morphed over time, it’s crucial to dig into these cultural differences and then spin that out to the global scale. There are all these complicated affinities between various types of patrimonial capitalism and the BJP project in India, where you have a Modi-aligned group of oligarchs who represent a certain cultural style, represent a certain mode of doing business in the country. And it’s at that level that the affinity is deep, where that relationship between the mass base of the BJP and globally relevant and listed corporations becomes thinkable. Because on the face of it, it would just seem not to go together.

But if it comes in a certain shading or cultural style, it works, which is why the Musk–Trump partnership is even thinkable in the current moment. It takes an Elon Musk version of billionairedom to establish this relationship. Certain things will go together and other things won’t in this time of testing. And it’s not ‘a one size fits all’, as it’s not a single cultural mode.

One of the great fallacies of US liberalism in particular is to think that one size does fit all. The best law school, the best corporate job, connections in California and Hollywood and Silicon Valley. How could a candidate like that not be electable? There’s a mental failure on the part of the US liberal elite to understand how that specific combination of power, cultural privilege, economic privilege, could in fact be profoundly distasteful to a solid majority of the American population.

At some level corporate power is aligned with the professional managerial class....those social groups are deeply enmeshed with a structural and cultural liberalism that is toxic to the MAGA crowd.... They are instead attracted to a petit bourgeois model, what some analysts in the US called the American gentry....I think understanding the way in which the relationship between populist politics and capitalism has morphed over time, it’s crucial to dig into these cultural differences and then spin that out to the global scale.

Nick: What responses do you have to the increased militarism, the increasing US–China hostility, and the tension between their economic interrelations and increasing drive towards war.

Walden: We have seen the US–China relationship transformed from a partnership to rivalry in less than a decade. Throughout the last 10 years, we have seen the US take the lead in defining China as a rival, while China has consistently called for a return to what it calls normal relations with the US, that is to the partnership of the period between the late 1980s and 2016. China has also disclaimed its intention of replacing the US as the global hegemon and has not promoted an alternative multilateral system to the Bretton Woods system.

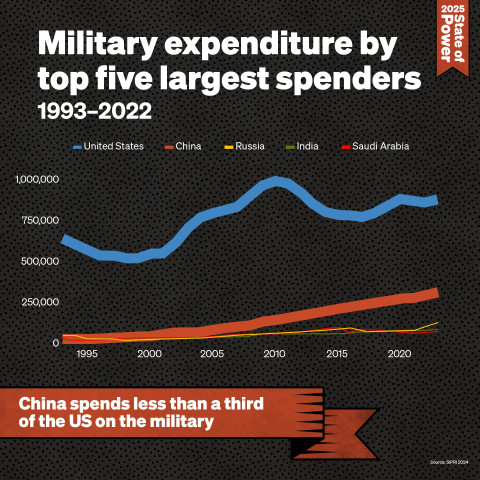

The new development bank and contingency reserve arrangements of the BRICS system remain purposely underdeveloped. Though it has increased defence spending, China has not made any leaps in spending with the US which is consistently spending about three times as much as Beijing over the last few years.

My sense is that Trump is likely to continue the trade and technology war with China, but I’m much less certain that he will carry out the military containment that was accelerated by the Biden administration. Trump is a synonym for unpredictability, but there’s a good chance that he will largely see the Asia-Pacific as being in China’s ‘sphere of influence’ politically and economically, while maintaining the rhetoric of continued US engagement with the region.

Now, there is an expectation among analysts as well as bureaucratic elites that a transition from one global hegemon to another is inevitable. But with the US likely to be hesitant under Trump, mainly because of realisation of constraints, to assume the old role of global hegemon and China unwilling to fill it, what we may see in the short and medium term might be a hegemonic vacuum, much like that in the interwar period in the twentieth century when Britain was too weak to perform the role of global hegemon and the US did not want to fill it.

Source: TNI based on SIPRI, 2024. https://milex.sipri.org/sipri

Nick: What do you see as implications of this hegemonic vacuum and what it means for low- and middle-income countries? And how should they navigate this process, in terms of opportunities and challenges?

Walden: Well, I agree with Adam that we have entered an era of what he calls polycrisis where the climate crisis, geopolitical rivalry, the North–South divide and the conflict between democracy and fascism will intensify. Now, there is that enigmatic line Gramsci used to describe this era that is also appropriate for ours: ‘The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters’. I guess what he was trying to say was that you cannot have opportunity without crisis.

With the emergence of a hegemonic vacuum or stalemate, the US–China relationship would continue to be critical, but neither will be able to decisively manage trends, such as extreme weather events, growing protectionism, the decay of the multilateral system that the US put in place during its apogee, the resurgence of progressive movements in Latin America and the rise of authoritarian states.

Nevertheless, I view the crisis of US hegemony as offering not so much anarchy but opportunity, although there are risks and great dangers involved. It can open up the path to a world where power could be more decentralised, where there could be greater freedom of political and economic manoeuvre for small, traditionally less-privileged actors from the Global South, playing off the two superpowers against one another. A truly multilateral order could be constructed through cooperation rather than be imposed through either unilateral or liberal hegemony.

So, taking off from Gramsci’s words, we may be entering an age of monsters, but like Ulysses, we cannot avoid going through the dangerous passage between Scylla and Charybdis if we are to get to the promised safe harbour.

Adam: I’m on the record that I find the Gramsci quote that Walden has cited unhelpful for thinking about the current moment because it almost promises too much. We read it now against the backdrop of knowing what happens next, which is that this period of interregnum ends and is then superseded by the 1940s’ settlement with two orders, a Western and US-dominated bloc and a Soviet-oriented bloc.

And I don’t think that’s promised to us in the current conjuncture. I don’t think the twentieth century is going to be a good model for thinking about the twenty-first century, any more than the nineteenth century was a good model for thinking about the twentieth century.

The future, for better and for worse is going to be more complex and more polycentric. That’s the world that we’re actually in and adjusting to, and which has many attractive features. Apart from anything else, it realigns the balance of cultural, economic, technological weight with the distribution of humanity. It moves us out of the grotesque disproportion of those factors that dominated the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries towards a much more balanced and rational allocation of resources.

But it also comes with real risks. I’m most worried about war. I didn’t think I would have to worry about war again. I’m a child of the late Cold War in Europe, and the prospect of nuclear annihilation was one that shaped my childhood but would not be one that shaped my adulthood, or of my child’s future and her children’s future.

I’m afraid that is the world that we’re back in. And the truly terrifying thing about the current moment are the deep, powerful interests on the US side, and no doubt they’re also deep and powerful on the Russian and the Chinese sides, which are increasingly committed to a tripolar nuclear arms race, as well as to control space, hypersonic [weaponry] and so on. It’s not the old nuclear arms race in terms of the technologies and the fact that it’s a three-player game.

We’re already seeing hawkish US think tanks argue for the direct targeting, for instance, of Chinese urban areas as the way of maximising the deterrent ‘bang for buck’ in an increasingly unmanageable tripolar world. And we’re just at the beginning, as this competition is maybe five years old.

Against that backdrop, one of the huge challenges for global progressive politics is that we have to engage with the peace question. This was core to global politics in the 1970s and 1980s. It was extremely difficult because it always opens you up to the allegation that you’re basically a fifth column for external threats, then the Soviet Union and/or China.

For decades we could delegate peace to Goldman Sachs, because as long as its CEO was running the strategic, economic relationship between China and the US, you knew that war was not on the agenda because too much money was going to be made.

But one of the side effects of the re-emergence of the nation-state and core national security interests as dominating policy debate is that progressive politics around the world must now argue for peace as the essential precondition for anything else good that we want.

Now, this does not necessarily mean a surrender on every single other front. It doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to flagrant human rights abuses, such as the repression of freedom of speech in Hong Kong. It’s very challenging, notably for the Western left, to articulate this position, because one should not kid oneself that these are simple matters. This is the classic terrain of progressive political dilemmas going all the way back to the period of the interwar period and the question of where one stood on appeasement. But it’s essential that we begin doing so because otherwise we’re going find ourselves enrolled in US power projects, which are essentially the anachronistic defence of America’s Cold War era position in East Asia.

This has also to be coupled with various types of autonomous, Gaullist, non-aligned moves such as a strong assertion by progressives of the importance of independent interests for regions, collectivities, entities like the EU [European Union], ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations].

It was very telling how, for instance, the Indonesian G20 presidency, in the full flush of the hysteria in the West over the Ukraine war, nevertheless took the position of saying ‘We, speaking for the rest of humanity, insist that there are other items on the agenda and we expect you, the United States, the Europeans, and China, to talk seriously about them as they are fundamental material issues to the majority of humanity’.

I’m not touting the Indonesian government as an example of radical progressive politics, but it is an indication of the leverage which major G20 players in this polycentric system can have. It’s not just the corporate state relationship that’s being tested. The entire power configuration is being tested in this moment.

And progressive politics has a huge stake in this how this works – at the level of trade policy, basic democratic rights, managing domestic power configurations and resisting some of these oligarchic combinations emerging in the national protectionist moment, and most fundamentally of all on the question of peace.

Progressive politics around the world must now argue for peace as the essential precondition for anything else good that we want.

Nick: Thank you, Adam. Walden, perhaps you could conclude with addressing the final question, how do social movements respond to this moment globally?

Walden: Yes, the dangers of war, especially for those of us in East Asia and the Philippines, is right there.

Over the last few years, under Biden, the containment of China, the provocative moves with respect to ships transiting the Taiwan Straits and the way he has unleashed the Pentagon or the military at least in terms of rhetoric is very problematic.

We had the head of the US Air Force Mobility Command, General Minihan, say, “We should be looking towards war with China in 2025.” During the Trump administration, it was mainly a trade and economic kind of conflict, but under Biden you had this escalation on the military front.

So, how do global social movements navigate this more complex world? Well, I fully agree that the peace question is something that we must embrace at this point, given the way that geopolitical rivalry has escalated. All sort of alliances need to be made and global coalitions need to be formed. And we must connect the climate crisis and other crises, such as the crisis of inequality.

[Groups like the] BRICS may be a largely potential rather than actual power, but it is a counterweight to the West and the multilateral order that that has been very oppressive. They also offer possibilities in terms of resources that can be used for development and for countries to pursue their own development agenda. Other formations may also emerge within the Global South that do not get caught up in this triple tug of war between the West and China and Russia.

Let me end by saying I have really enjoyed this dialogue. Thank you, Adam, for the wonderful exchange, and thanks, too, Nick and the Transnational Institute for organizing it.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: