Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Topics

Techno-nationalism could lead to an AI Iron Curtain, splitting the world into geopolitical blocs dominated by Big Tech powers and undermining digital sovereignty in the majority of the world. A locally driven, people-centred AI can help move us beyond Big Tech geopolitics.

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

The Tit-for-Tat Tech and Trade Wars

Artificial intelligence is the ability of computers or digital tools to perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent agents that imitate how we think and act. Today’s AI technologies are inspired by human neurophysiology and use computational models to process large amounts of data. Our current connectionist era of AI models can enhance their capabilities beyond their initial programming by employing advanced statistical learning methods. AI is prevalent in our daily lives, powering voice recognition in digital assistants like Siri and Alexa, and in generative chatbots, such as ChatGPT, which has reached 200 million weekly active users globally by mid-2024. It’s also used in projects like self-driving cars, identifying individuals to add on military kill lists, and creating new life-saving drug treatments.

The expansion of AI has become a defining force in the global landscape, as AI and its underlying supply chains and infrastructure have increasingly become means for geopolitical influence and the projection of power for decades to come. The global AI divide is also dominated by a handful of American and Chinese Big Tech firms, while most others are dependent on their technologies and techniques, this is signalling the emergence of a more hostile geoeconomics regarding Big Tech.

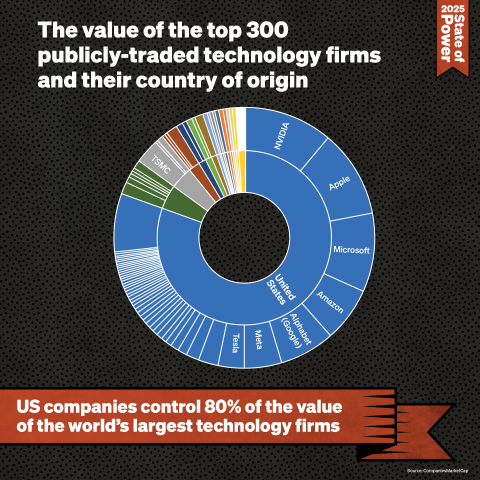

Figure 1 shows the market capitalisation of the top 300 publicly traded technology firms at the end of 2024. US Big Tech, notably Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, NVIDIA, Tesla and others comprise $25 trillion of the global total of $31 trillion, or 80% of the global technology sector’s valuation. Their dominance underscores the market size of US Big Tech due to their early pioneering role in defining this sector, but it is also unsustainably overvalued.

Then come the Chinese Big Tech like Alibaba, Baidu, Bytedance, Pinduoduo, Tencent and Xiaomi, whose combined market valuation is $1.4 trillion, or 4.5% of the total, followed by Taiwanese firms, like TSMC and Foxconn with 4.4%, and Japanese companies Sony and others with 2%. The Netherlands holds 1.4%, South Korea and Germany each have 1%, Canada 0.9%, and Israel and France round out the top ten players.

Contrary to the US Big Tech companies, the valuation of Chinese tech firms and their related supply chains and infrastructure manufacturers, such as China Telecom, Huawei, SMIC and ZTE has been significantly undervalued in recent years. This is due to the numerous US sanctions restricting them, such as denying access to advanced computer chips. This is further compounded by them being delisted from US stock exchanges. These measures were imposed on the grounds of national security concerns aimed at reducing the global market for Chinese technology firms and their footprints, especially in Western countries.

The US war on Chinese Big Tech has increased since 2015, with roots dating back to 2010, when Google halted operations in China after refusing to further censor content on Google.cn, following sophisticated cyberattacks linked to China.

The US sanctioned the Chinese telecom giant ZTE in 2016 for exporting to Iran and North Korea and later imposed a $1.4 billion fine. The house arrest of Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver on the request by the US in December 2018 and was only later released in September 2021 in exchange for two Canadians held in China. In 2019, the US Department of Commerce added Huawei and over 100 affiliates worldwide to its sanction Entity List. In 2021, US investors were prohibited from holding stocks in major Chinese Tech firms like Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent. Later that year, China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom were delisted from the New York Stock Exchange.

By the end of 2021, the US had imposed more than 9,400 unilateral sanctions against China. The US justified its sanctions by claiming that China engages in unfair competition, state subsidies, and economic espionage, issues that also underpin national security concerns for some other countries.

As a sign of the Chinese state’s power over its Big Tech, 33 leading Chinese tech companies, including Alibaba, ByteDance, Huawei, and Tencent, signed the Internet Platform Operators Anti-Monopoly Self-Discipline Convention at the 2021 China Internet Conference in Beijing. This agreement commits these firms to refrain from monopolistic practices. This signing happened after Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma, went missing for three months. He only reappeared again in late January 2021. Soon after, his company was fined a record $2.8 billion in April 2021 for violating Chinese anti-monopoly legislation.

By 2024, over 1,400 Chinese entities were placed on various US sanction lists, doubling in just four years. This aggressive crackdown has had a significant impact. In 2019, Chinese Big Tech held around 20% of the global market value. By the end of 2024, this had fallen to under 5%, almost on par with the self-governing island of Taiwan.

These actions have significantly skewed international perceptions of China’s AI capabilities, particularly regarding investment, and research and development (R&D). Despite this, China continues to lead in AI research and patent outputs, demonstrating its substantial progress and technical influence.

Moreover, in retaliation against US sanctions, at the end of 2024 China banned the export of critical earth minerals to the US, which are needed for manufacturing AI chips. This followed earlier actions in 2023 when China stopped the export of rare earth mineral processing technologies and banned the sale and use of Apple iPhones across government agencies. In January of 2025, China has further sanctioned 28 US entities, including US defence contractors like General Dynamics, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon.

These tit-for-tat measures are part of an intensifying tech and trade war escalation reflecting the Big Tech geopolitics.

Digital Divide: The New AI Iron Curtain and the Quest for Economic Sovereignty

Since the launch of public-facing generative AI like ChatGPT in November 2022, countries have become more interested in developing homegrown AI. A critical aspect of generative AI models is their ability to capture and codify a people’s public discourse by drawing from the vast collection of material and culture published on the Internet.

The Internet, which serves as the primary source of data scraped to train generative AI models, is inherently fragmented and significantly skewed, reflecting disparities in access, representation, and the dominance of certain languages, cultures, and perspectives. For instance, at the end of 2024, 2.6 billion people still lacked internet access, representing about a third of the global population. Hence, this unconnected one-third of the global population is not represented in any generative AI model.

In other words, the digital divide is directly giving way to an emerging AI divide made up of AI haves and have-nots. Under the current Big Tech geopolitics, these divides may worsen, fuelled by raising economic and security containment and chokepoint policies, risking dividing the world into opposing sides of a new AI Iron Curtain.

Examples include but are not limited to, the US restrictions on advanced AI chips from AMD, Intel, NVIDIA, Taiwan’s TSMC, and the Netherlands’ ASML. These restrictions aim to limit China’s high-performance computing capabilities by establishing distinct geopolitical AI ecosystems and infrastructure re-alignments.

Despite US export controls on advanced computing chips aimed at shutting out China from making advancements in AI, Hangzhou-based DeepSeek’s R1 model, launched in early 2025, still managed to turn these restrictions into opportunities for innovation in building more efficient open models. R1 competes with models like OpenAI’s GPT-4o, achieving benchmark performance while using significantly less compute power, financial, and energy resources.

This advancement has caused concern in Washington and Silicon Valley, undermining US dominance in AI and the geopolitics of Big Tech. It has led to a strategic re-evaluation of policies focused on export controls and maintaining its competitiveness.As the competition between the US and China over AI heats up, other countries are becoming more interested in and are investing in their sovereign AI infrastructure, like Gefion, Denmark’s first AI supercomputer that came online at the end of 2024. India is also poised to launch its own foundational AI model this year supported by a new line up of homegrown affordable computer facilities.

We are also seeing more techno-nationalism in calls to strengthen industrial policies and build out national AI stack architecture. This is not necessarily a bad thing - to have local hardware for local users to address local needs. A domestic or national AI stack embodies homegrown efforts to establish a self-reliant and controlled technology and AI ecosystem, reflecting broader trends in digital sovereignty through localizing standards, infrastructure and hardware control and more restrictive data governance.

Another way these competitions are reviving calls for digital sovereignty is by implementing local content requirements to boost domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on imported technology. For example, Indonesia, the world’s fourth-most populous country with over 280 million people, has banned Apple’s iPhone 16 and Google’s Pixel smartphones for failing to meet its 40% locally sourced component requirement. In response to the ban, Apple proposed a $100 million investment to build an accessory and component plant in the Southeast Asian country.

Nevertheless, these tensions and changing Big Tech geopolitics may serve to divert critical resources and capital towards renewed geopolitical competition, prioritizing winning the global AI race and dominance over knowledge. They also threaten to erode any semblance of a rules-based international order toward erecting a new AI Iron Curtain, marked by new restrictions on people’s movements, technology transfers, scientific collaborations, and data flows.

These trends may re-align national AI ecosystems’ value chains, supply chains, and their underlying digital and social infrastructure. They may also lock us into costly duplications and fragmented AI and technology ecosystems, diverting much-needed resources and scientific enquiry that could otherwise address shared challenges, such as climate action and public health.

This is made more explicit in the competition over undersea cables connecting Southeast Asia to Europe. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, for example, has a Digital Silk Road (DSR) component involving 40 countries, which is funded by state-owned banks and financial institutions like the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, and Chinese tech giants such as Alibaba, Huawei, Tencent and ZTE. One of its notable projects is the completed Pakistan & East Africa Connecting Europe (PEACE) undersea cable, a 21,500 km network connecting France, Pakistan, and Singapore by Huawei Marine’s successor, HMN Technologies, to the tune of $425 million.

To rival China’s BRI, the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) was launched, with the aim to raise $600 billion by 2027, especially from the US, the European Union (EU) and Japan. The initiative seeks to strengthen and diversify global supply chains and support shared security interests. PGII is being funded by multilateral development banks (MDBs), sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), and private capital sources, such as BlackRock and Brookfield global investment corporations. A flagship project awarded a $600 million contract to the US company SubCom to build the 17,000 km Southeast Asia-Middle East-West Europe 6 (SMW6) undersea cable, connecting Singapore to France via Egypt after HMN Technologies was dropped as the preferred supplier.

Furthermore, on university campuses in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Germany, and elsewhere, there is growing concern and scrutiny that scholars may have unintentionally cooperated with Chinese military scientists, particularly those from the National University of Defence Technology (NUDT). Concerns about national security have been raised about the possible transfer of sensitive and key technologies, like AI and quantum, to the Chinese military, as well as Chinese interference in the scientific research ecosystems, stoking anti-Chinese sentiments.

On the other hand, these trends are not without contradictions. For example, Microsoft has contributed significantly to China’s AI capabilities through collaborations with Chinese institutions, such as Microsoft Research Asia’s (MSRA) AI lab in Beijing and has partnered with NUDT. Indeed, the AI Iron Curtain have many gaps as these openings and links are essential, if not inevitable.

Likewise, the role and place of military science is also not new to the discovery and development of advanced technologies. It is also militarising Big Tech. We see this in the origins of the university-industry-defense triple helix model of innovation that gave rise and continues to support Silicon Valley.

Looking ahead, the AI Iron Curtain appears likely to extend into space. For instance, China’s Chang’e 6 Lunar Exploration Mission returned first-ever samples from the far side of the moon in June 2024, but US research scientists cannot view the samples because of the restrictive 2011 Wolf Amendment, which forbids NASA from collaborating directly with China without security approval. Although China invited international scientists to study the samples, the US has erected a self-imposed barrier, stifling beneficial cooperation and hindering progress in this and other critical areas of common interests.

Local and People-Centred AI from Digital Justice Communities

Global digital justice communities offer alternative visions to the Big Tech status quo by promoting cooperation on data and investing in building public digital infrastructure. They treat data and AI as public goods, focusing on local, people-centered solutions. By aligning themselves with ethical and equitable principles, these communities aim to ensure that technological advancements meet local needs and empower people and communities.

They advocate for open-source AI models and more inclusive and localized ecosystems, challenging Big Tech’s geopolitical ambitions of their dominance over knowledge. Under this likely scenario of Big Tech geopolitics, it will further reinforce regional blocs and rising techno-nationalism, potentially leading us toward a riskier world divided by a new AI Iron Curtain.

It puts the focus back on how we could ensure AI tangibly improves people’s lives, including data workers like Janaki and Rajesh in the Majority World, and the health of the planet.

Box 1 lists six people-centred and digital justice communities and others that make five broad recommendations and strategies for re-aligning AI systems toward serving people’s needs.

Box 1. Recommendations and strategies for re-aligning AI towards local and people needs

IT for Change, The Balanced Economy Project, and People vs. Big Tech, a global coalition of civil society and academics 2024 white paper Beyond Big Tech: A Framework for Building a New and Fair Digital Economy.

United Nations and International Labour Organization (ILO) 2024 report Mind the AI Divide: Shaping a Global Perspective on the Future of Work.

Association for Progressive Communication (APC) 2024 report Communal Internet Infrastructure: An Alternative, Self-Managed Approach to Digital Spaces Built Upon Values of Community, Autonomy, and Collaboration.

T20 Brazil 2024 Policy Brief Governing Computational Infrastructure for Strong and Just AI Economies and other papers by the Inclusive Digital Transformation.

Tierra Común Network’s 2023 book, Resisting Data Colonialism: A Practical Intervention.

Democratic and Ecological Digital Sovereignty Coalition 2024 proposal Reclaiming Digital Sovereignty: A roadmap to build a digital stack for people and the planet.

We end with five key recommendations for building more local and people-centered AI:

1. Promote open and decentralised Public Digital Infrastructure (PDI)

Investing in open-source platforms and decentralised and public-led digital stacks is crucial to counteracting the dominance of Big Tech. Public digital infrastructure and its supporting layers should operate as digital commons, supported by community ownership and accountable governance frameworks that prevent resource chokepoints and structural lock-ins. These systems need to be aligned with human rights standards to ensure equitable access and usage.

Initiatives like guifi.net in Spain and Rhizomatica in Mexico, for example, empower local communities to build and manage their internet infrastructure, ensuring connectivity in underserved regions. MTLWifi in Montreal offers free Wi-Fi access in 275 public spaces such as libraries and parks. There are many other examples of municipal Wi-Fi across Europe.

2. Break up monopolies

Strong antitrust laws and competition regulations, particularly in the US, need to be strictly enforced to better balance Big Tech’s structural dominance, regulatory capture, human capital, and financial strength. Key measures include breaking up monopolies, mandating interoperability (which ensures that products and services from different providers can interact and work together), fostering competition across AI value chains, increasing public investment and ownership of AI infrastructure and related resource inputs, and using taxation to redistribute the gains of dominant tech firms.

Doing so would level the playing field and open markets to new entrants. For instance, there are various proposals to separate Amazon’s roles as a cloud provider, and as a retailer from its function as a marketplace for third-party sellers, to address its self-preferential treatment whereby Amazon competes with businesses on its e-commerce platform.

3. Build a digital Non-Aligned Movement

The movement is inspired by the political Non-Aligned Movement, which currently numbers 120 countries, many of which historically sought independence by breaking away from their structural dependence on major powers, while enhancing digital equity and resilience against fragmentation. This approach involves nations and regions developing policies, technologies, and collaborations that avoid overly aligning with dominant AI and innovation ecosystems like those of the US and China.

For instance, Brazil’s digital transformation focuses on leveraging technology to promote social inclusion, improve public services and build an equitable digital economy, including developing public software. Central to this transformation is its strong emphasis on favouring free, libre, and open-source software (FLOSS) and locally tailored solutions that reduce dependency on foreign Big Tech and encourage national and homegrown innovation, such as community-based Mumbuca – a people’s fintech.

4. Prioritise people-centred and locally inclusive innovation

Policies should prioritise people-driven technological and AI innovation, emphasising fairness, better working conditions, equity and environmental sustainability across global and local AI value chains. They should encourage the development of smaller-scale, context-specific AI models while reducing dependency on concentrated AI value chains and supply chains. This is done to ensure that innovations and their associated infrastructure like the availability of ample electricity supply continue to serve diverse local needs and contexts.

For example, MobileNet is the name of a frugal AI model design. Its lightweight neural networks are designed to operate efficiently on mobile devices. By requiring minimal computing power, data and energy, MobileNet offers effective and more affordable solutions without compromising performance, making it ideal for resource-constrained environments and applications.

5. Strengthen civil society advocacy

Civil society organisations (CSOs) and researchers need to be resourced and equipped to advocate for more robust data-protection laws, and ethical and people-centred AI practices and governance. Empowering and partnering with local communities to find alternatives to exploitative practices and harms and to demand equitable resource distribution is critical for driving systemic change and holding governments and Big Tech accountable.

These five recommendations and strategies highlight a dual approach: breaking down Big Tech’s monopolistic power while actively re-aligning them to build responsible, local, and inclusive innovation ecosystems. In this, it is critical to strengthen the ‘right to science’ and its associated benefits for people and the planet as guaranteed in Article 27 of the 1948 United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

This aligns with the 2024 report by the Special Rapporteur on cultural rights, which emphasised the need for more inclusive access to and participation in scientific advancements.

Digital justice communities and their human right defenders play an essential role in their immediate local communities, in both the Majority World, as well as the Minority World. Their mobilisation and coalition-building efforts across all sectors and partners can galvanise much-needed awareness and resources for public debate and investment in public digital infrastructure needed in developing and deploying more locally driven, people-centred AI.

To close the digital and AI divides, the road ahead is challenging. Fostering stronger local and open ecosystems could help ensure that technology and science benefit more people, not just the powerful few in moving us beyond Big Tech geopolitics.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: